Bottom: Park River c. 1895. Archives, Connecticut State Library. Top: Hartford Collection, Hartford Public Library

By Sandra Wheelers

photos selected by Nancy O. Alberts

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2002

Subscribe!

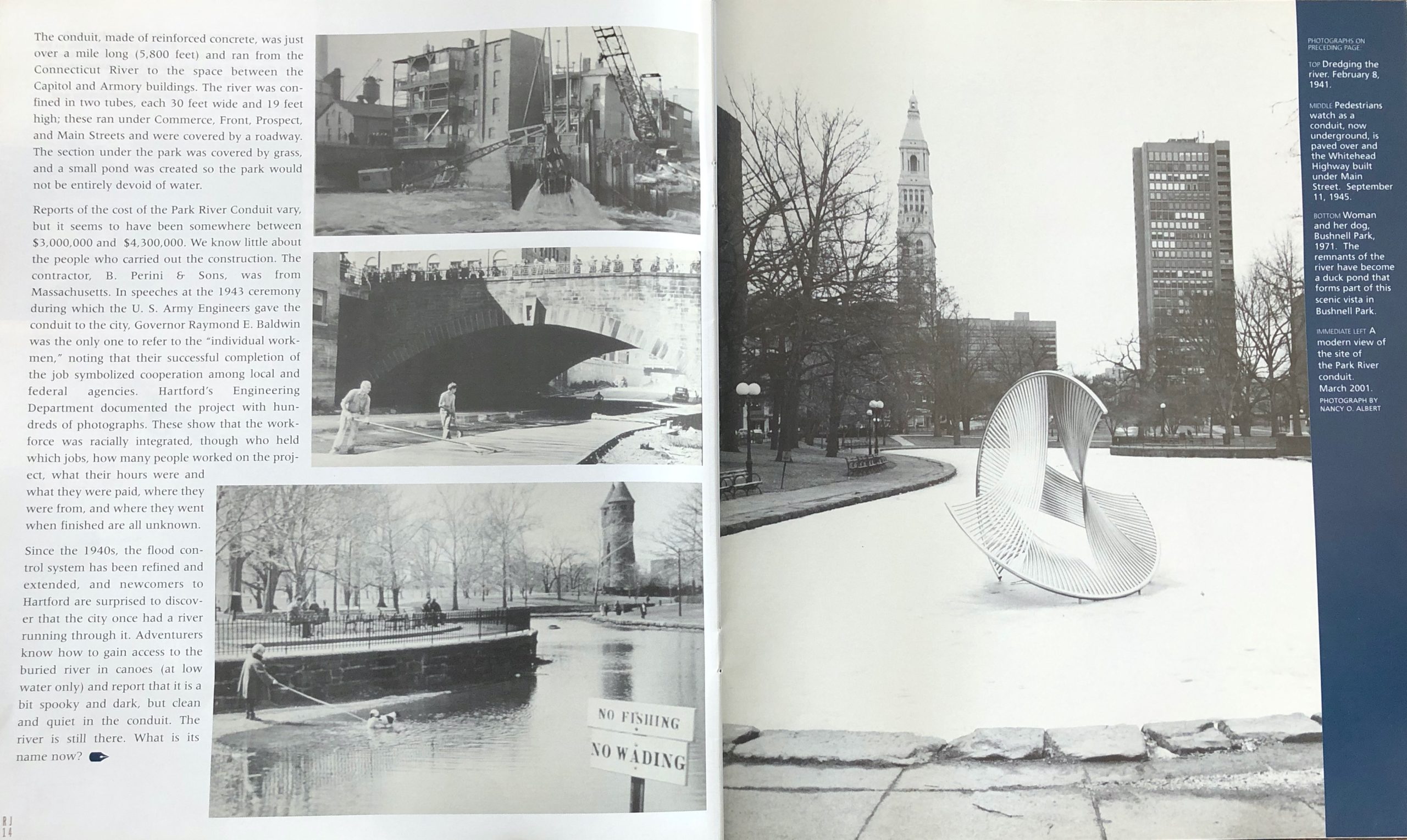

There are numerous images of the Park/Hog River in city and state archives. Because it flowed through central portions of the city close to the state capitol and other landmarks and because its frequent floods were typically newsworthy, a wealth of image exist. The details in these photographs provide valuable information about Hartford’s changing landscape.

HARTFORD HAS ITS OWN RIVER, one it doesn’t share with Springfield or Middletown. Once upon a time it was called the Little River, so it would not be confused with the Great (Connecticut) River. After Bushnell Park was created around it in the mid-19th century, the stream became known as the Park River. This rather generic, genteel name was fitting for a city that specialized in insurance and avoided risk.

Before Bushnell Park, though, it was the Hog River. That colorful name came from the river’s function when the city was in its first spurts of growth and prosperity: it received the refuse and waste from the tenements and factories that hugged its edges. The name conveys a sense of willfulness and reluctance to be tamed which was appropriate, for the river did not do its job. Instead of reliably flushing nasty messes from the city, it brought disease when its waters were low and devastation when they were high. It was dangerous, and changing its name and putting it in a park did not lessen its potential to cause destruction.

The disease carried by the river in the summers was accepted as part of life, especially since only the poorer of the city’s citizens lived near enough to be affected by the water-borne illnesses. The floods, however, were a different matter. When the Connecticut River was high, it backed up Hartford’s river into the city. Unlike the slow, chronic wasting of health and life the dirty waters inflicted on the tenement dwellers, floods were dramatic, their devastation quick and obvious. They damaged property, and the post-flood cleanups cost lots of money.

The floods of 1936 and 1938 were particularly expensive, and city, state, and even federal authorities paid attention. After the 1936 flood, Mayor Spellacy established a Flood Control Commission, and the even bigger flood two years later added urgency to that commission’s work. Also by late 1938, the U.S. War Department was interested, for increasing concern over the likelihood of war in Europe meant America’s rapidly expanding defense industry in the Hartford area had to be protected from any loss of time or materials. Plans for a system of dikes along the Connecticut River and for putting Hartford’s river underground in what was known as the Park River Conduit were first created by the Hartford Department of Engineers and then taken over and finalized by the Office of the District Engineer of the War Department. That office also supervised construction, which began in September 1940 and was completed in November 1943.

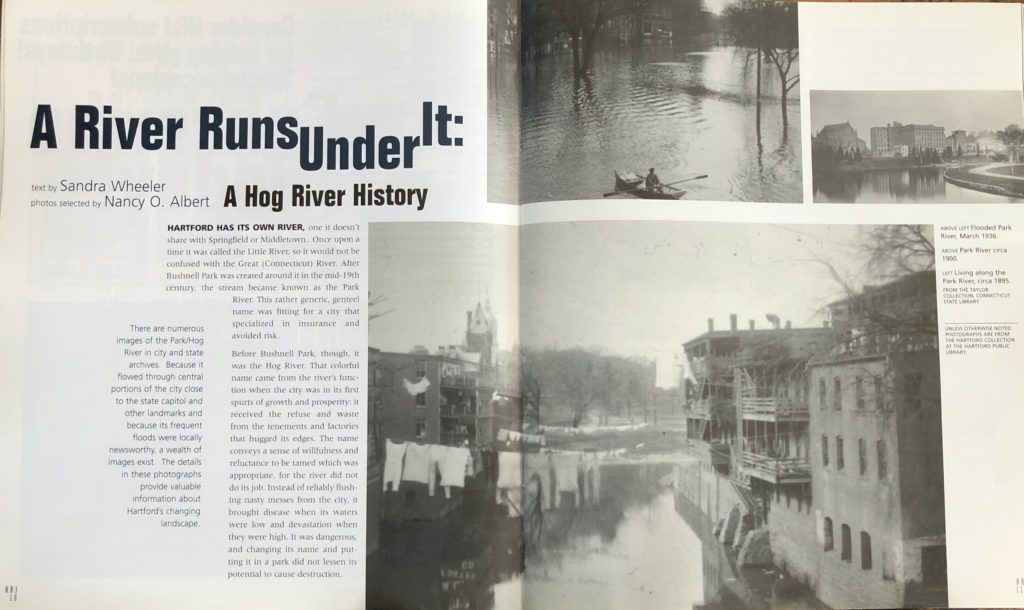

The conduit, made of reinforced concrete, was just over a mile long (5,800 feet) and ran from the Connecticut River to the space between the Capitol and Armory buildings. The river was confined in two tubes, each 30 feet wide and 19 feet high; these ran under Commerce, Front, Prospect, and Main Streets and were covered by a roadway. The section under the park was covered by grass, and a small pond was created so the park would not be entirely devoid of water.

Reports of the cost of the Park River Conduit vary, but it seems to have been somewhere between $3,000,000 and $4,300,000. We know little about the people who carried out the construction. The contractor, B. Perini & Sons, was from Massachusetts. In speeches at the 1943 ceremony during which the U. S. Army Engineers gave the conduit to the city, Governor Raymond E. Baldwin was the only one to refer to the “individual workmen,” noting that their successful completion of the job symbolized cooperation among local and federal agencies. Hartford’s Engineering Department documented the project with hundreds of photographs. These show that the workforce was racially integrated, though who held which jobs, how many people worked on the project, what their hours were and what they were paid, where they were from, and where they went when finished are all unknown.

Since the 1940s, the flood control system has been refined and extended, and newcomers to Hartford are surprised to discover that the city once had a river running through it. Adventurers know how to gain access to the buried river in canoes (at low water only) and report that it is a bit spooky and dark, but clean and quiet in the conduit. The river is still there. What is its name now?