(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

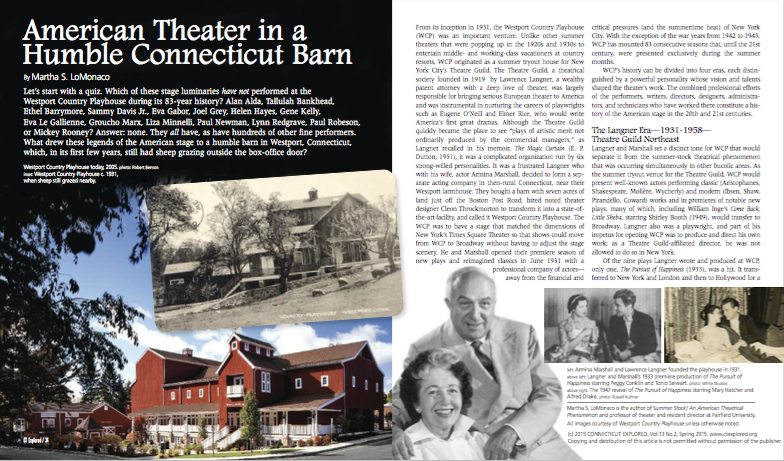

Let’s start with a quiz. Which of these stage luminaries have not performed at the Westport Country Playhouse during its 83-year history? Alan Alda, Tallulah Bankhead, Ethel Barrymore, Sammy Davis Jr., Eva Gabor, Joel Grey, Helen Hayes, Gene Kelly, Eva Le Gallienne, Groucho Marx, Liza Minnelli, Paul Newman, Lynn Redgrave, Paul Robeson, or Mickey Rooney? Answer: none. They all have, as have hundreds of other fine performers. What drew these legends of the American stage to a humble barn in Westport, Connecticut, which, in its first few years, still had sheep grazing outside the box office door?

From its inception in 1931, the Westport Country Playhouse (WCP) was an important venture. Unlike other summer theaters that were popping up in the 1920s and 1930s to entertain middle- and working-class vacationers at country resorts, WCP originated as a summer tryout house for New York City’s Theatre Guild. The Theatre Guild, a theatrical society founded in 1919 by Lawrence Langner, a wealthy patent attorney with a deep love of theater, was largely responsible for bringing serious European theater to America and was instrumental in nurturing the careers of playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill and Elmer Rice, who would write America’s first great dramas. Although the Theatre Guild quickly became the place to see “plays of artistic merit not ordinarily produced by the commercial managers,” as Langner recalled in his memoir, The Magic Curtain (E. P. Dutton, 1951), it was a complicated organization run by six strong-willed personalities. It was a frustrated Langner who with his wife, actor Armina Marshall, decided to form a separate acting company in then-rural Connecticut, near their Westport farmhouse. They bought a barn with seven acres of land just off the Boston Post Road, hired noted theater designer Cleon Throckmorton to transform it into a state-of-the-art facility, and called it Westport Country Playhouse. The WCP was to have a stage that matched the dimensions of New York’s Times Square Theater so that shows could move from WCP to Broadway without having to adjust the stage scenery. He and Marshall opened their premiere season of new plays and reimagined classics in June 1931with a professional company of actors—away from the financial and critical pressures (and the summertime heat) of New York City. With the exception of the war years from 1942 to 1945, WCP has mounted 83 consecutive seasons that, until the 21st century, were presented exclusively during the summer months.

WCP’s history can be divided into four eras, each distinguished by a powerful personality whose vision and talents shaped them. The combined professional efforts of the performers, writers, directors, designers, administrators, and technicians who have worked there constitute a history of the American stage in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Langner Era—1931-1958—Theatre Guild Northeast

Langner and Marshall set a distinct tone for WCP that would separate it from the summer stock theatrical phenomenon that was occurring simultaneously in other bucolic areas. As the summer tryout venue for the Theatre Guild, WCP would present well-known actors performing classic (Aristophanes, Shakespeare, Molière, Wycherly) and modern (Ibsen, Shaw, Pirandello, Coward) works and in premieres of notable new plays, many of which, including William Inge’s Come Back, Little Sheba, starring Shirley Booth (1949), would transfer to Broadway. Langner also was a playwright, and part of his impetus for opening WCP was to produce and direct his own work; as a Theatre Guild-affiliated director, he was not allowed to do so in New York.

Of the nine plays Langner wrote and produced at WCP, only one, The Pursuit of Happiness (1933), was a hit. It transferred to New York and London and then to Hollywood for a movie version in 1934. It also was adapted into a musical, Arms and the Girl, in 1950. Marshall collaborated with him on Pursuit and was, as Langner notes in The Magic Curtain, the presiding genius who transformed his serious play about equality under the Declaration of Independence into a comedy that became famous for its “bundling” scene. Bundling was a courtship practice in colonial America wherein a couple would “bundle” in bed in the woman’s family home, fully clothed and with a solid wooden board between them, to test their compatibility for marriage. In the play, the board disappears and the couple is discovered scandalously “unbundled.” According to Langner, during preview performances Marshall, referring to the actors, cried, “Those kids haven’t the faintest idea how to bundle!” and, temporarily dismissing the director, restaged the scene to emphasize its comedic possibilities. Overnight, the play became a hit and moved directly to New York with its WCP cast, featuring up-and-coming Broadway stars Peggy Conklin and Tonio Selwart, and played an entire season. WCP revived the play in 1947 with Alfred Drake and Mary Hatcher in the leading roles.

The McKenzie Era—1959-1999—The Golden Age of Summer Stock

The Langner family’s reign at WCP—with Langner and Marshall’s son Philip as a major producing partner throughout the 1950s—segued smoothly into James B. McKenzie’s 41-year directorship in 1959. Philip, who was not associated with the Theatre Guild and its ideals, began WCP’s transformation to a playhouse that focused on stars performing in recent Broadway hits. McKenzie kept that model, and WCP was reinvented as a summer stock theater.

McKenzie was a veteran of summer stock. He was owner and producer of the Peninsula Players in Fish Creek, Wisconsin, and a producer, director, stage manager, stagehand, press agent, and trumpet player in 18 other venues. Although Philip Langner had initiated WCP’s association with the Council of Stock Theatres (COST) summer circuit, McKenzie exploited it to its full advantage and thereby brought the stars to Westport in droves. Via the COST network, a show would be cast, rehearsed, and mounted in New York City and then sent out on the road to play all the principal summer stock houses.

McKenzie was a veteran of summer stock. He was owner and producer of the Peninsula Players in Fish Creek, Wisconsin, and a producer, director, stage manager, stagehand, press agent, and trumpet player in 18 other venues. Although Philip Langner had initiated WCP’s association with the Council of Stock Theatres (COST) summer circuit, McKenzie exploited it to its full advantage and thereby brought the stars to Westport in droves. Via the COST network, a show would be cast, rehearsed, and mounted in New York City and then sent out on the road to play all the principal summer stock houses.

“When I started at WCP in 1959, COST had 52 theaters to fill, and we needed to decide who would get what show in a given week,” McKenzie told me in a 1992 interview for my book Summer Stock! An American Theatrical Phenomenon (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). “It was mayhem. All the producers would shout what dates we would want. Everyone’s objective was to not have a dark week. If you had one, then you’d have to do a local show, which was a lot of work.” Although WCP continued to mount shows itself, it was largely through COST that McKenzie was able to book star performers in plays that had been recent hits in New York.

Big stars happily played the summer circuit, since they were guaranteed a full three months’ employment at handsome salaries. Liza Minnelli made her stage debut at WCP in The Fantasticks (1964), Mickey Rooney starred in See How They Run (1972), Lynn Redgrave in The Two of Us (1975), and Geraldine Page and Sandy Dennis in Agnes of God (1984). Occasionally, pre-Broadway tryouts still came to WCP and went to New York to become major hits; a notable example is Butterflies Are Free with Blythe Danner and Keir Dullea (1969).

WCP’s most memorable stories are the ones where the stars acted like . . . stars. When Shelley Winters came to Westport in 84 Charing Cross Road (1983), she pulled a classic star maneuver—but in a way that endeared her to audiences. In An American Theatre: The Story of Westport Country Playhouse 1931-2005 (Yale University Press, 2005), Richard Somerset-Ward notes that Winters was more than an hour late for a Wednesday matinee on a particularly hot July afternoon. The frustrated crowd of mostly older women, impatiently waiting for the show to begin, were enjoying free beverages in the garden, courtesy of the management, when Winters frantically arrived by car. “Out jumps Ms. Winters…. Her hair is in curlers and she is clutching what seems like fifty shopping bags. She dives into the center of the lynch mob, which has been silenced by her screeching wheels, and at the top of her lungs she screams out, as though these were all her best friends: ‘My dears, it was AWFUL. . . .’” The crowd quickly followed her into the theater and the show finally started. Although the audience never actually ended up hearing Winters’s tale of distress, it didn’t matter: her “star power” ensured that the performance was a hit.

McKenzie kept the stars coming, but as other summer stock theaters closed down and the COST circuit went from 52 theaters in the 1960s to only 3 in the 1990s, it became increasingly difficult to attract stars for less than a full summer’s employment. When McKenzie announced his retirement in January 2000, it was apparent that if WCP were to remain viable, a new approach was needed.

The Woodward Era—2000-2006 and 2008—“Picking up where Lawrence and Armina Started”

Academy-award winning actor Joanne Woodward, who had lived in Westport with her husband Paul Newman since 1961, was a longtime supporter of WCP, but she had never performed there, much less ever dreamed of becoming its artistic director. “Never in my wildest imagination did I think I’d ever do something like this,” she told me in a 2001 interview. Once she was coaxed into taking the job, with her friend and professional colleague Anne Keefe as her artistic associate, Woodward decided that WCP’s new direction would be to recapture the excellence of the old. She said she wanted to “pick up where Lawrence and Armina started in 1931” by offering vibrant seasons that would include challenging new plays and revivals of the great shows of the past. Under her directorship, such hits from the golden age of summer theater as Sutton Vane’s Outward Bound (2002), John Van Druten’s The Voice of the Turtle (2002), and Carson McCullers’s A Member of the Wedding (2005), rarely revived elsewhere, were produced, along with new works including Richard Greenberg’s Three Days of Rain (2001) and The Good German by resident playwright David Wiltse (2003). “I want to stir the audiences’ heads up a bit and give them a surprise or two,” Woodward said in our interview. “If you come out of the theater and you don’t talk about what you saw, it’s hard to say that that’s theater. I like it when there are arguments and people are vigorously disagreeing—that’s how it should be.”

The most famous production during her tenure was the 2002 revival of Our Town, originally presented at the playhouse in 1946 with playwright, Yale graduate, and Hamden resident Thornton Wilder playing the role of the stage manager. The new production starred Paul Newman with a supporting cast that included Frank Converse, Jane Curtin, Jeffrey DeMunn, Mia Dillon, and Stephen Spinella. In the fall the show moved to Broadway, where it played a sold-out nine-week engagement and was filmed for Masterpiece Theatre’s American Collection and aired nationwide on public television. “The transfer to Broadway was important because we wanted to be thought of as a theater on the edge,” Anne Keefe told me in a December 2002 interview. “We wanted to propel a change in the caliber of scripts and artists that would come to us if we got this kind of national and, indeed, international exposure.” The timing of Our Town was perfect, both in fulfilling Woodward’s vision of re-imagining WCP as it had been in 1931 and propelling the $30-million fundraising campaign to renovate and expand its facilities. In May 2005 Woodward opened the revitalized playhouse, a state-of-the-art 21st-century theater that still looked like a traditional red barn, with local resident and longtime WCP board member Christopher Plummer presenting his hit one-man show A Word or Two Before You Go. When Woodward stepped down after a six-year tenure as artistic director she was succeeded as artistic director by Tazewell Thompson, who held the job for only two years. Woodward—always the trouper—returned with Keefe for one final season in 2008 until her permanent successor could be found.

The Lamos Era—2009 to the present—Artistic Powerhouse

In naming the Westport Country Playhouse as “company of the year” in his end-of-year assessment of the 2013 theater season—artistic director Mark Lamos’s fourth season, Wall Street Journal drama critic Terry Teachout credited Lamos with transforming the playhouse into “an artistic powerhouse.” Teachout noted, “Few regional companies are striking so satisfying a balance between familiarity and adventurousness” and cited Lamos’s “superior staging” of A.R. Gurney’s The Dining Room as a season highlight.

A world-renowned director of dramas, musicals, and operas, Lamos was no stranger to Connecticut audiences when he arrived at WCP. He spent 17 years (1980-1998) as artistic director at Hartford Stage, which, under his stewardship, was awarded the 1989 TONY award for best regional theater. In 2008 Lamos was asked to step in for an ailing Paul Newman, who had been slated to direct the season’s opening production, a revival of the stage adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men; Lamos began his tenure as artistic director the following year. As a seasoned artistic director in regional theater, Lamos was well suited to continue Woodward’s transformation of WCP from star-studded summer stock house to resident repertory theater in the spirit of Langner and Marshall, where the excellence of productions did not rely on celebrity performers but rather on solid actors. However, this perspective is not always shared by local audiences, who miss the steady stream of stars that entertained them for 40 years. “I love the actors we have here; they are top quality,” Lamos told me in an interview for this article, noting that WCP is the only Connecticut theater that has been known principally for hiring stars. He takes pride in the excellence of the acting ensembles that WCP attracts and cited the 2014 revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s Things We Do For Love, with veteran Broadway director John Tillinger at the helm, as “some of the best ensemble comedy acting [by Geneva Carr, Matthew Greer, Sarah Manton, and Michael Mastro]I have ever seen anywhere, not just on this stage but anywhere. It was impeccable.”

A world-renowned director of dramas, musicals, and operas, Lamos was no stranger to Connecticut audiences when he arrived at WCP. He spent 17 years (1980-1998) as artistic director at Hartford Stage, which, under his stewardship, was awarded the 1989 TONY award for best regional theater. In 2008 Lamos was asked to step in for an ailing Paul Newman, who had been slated to direct the season’s opening production, a revival of the stage adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men; Lamos began his tenure as artistic director the following year. As a seasoned artistic director in regional theater, Lamos was well suited to continue Woodward’s transformation of WCP from star-studded summer stock house to resident repertory theater in the spirit of Langner and Marshall, where the excellence of productions did not rely on celebrity performers but rather on solid actors. However, this perspective is not always shared by local audiences, who miss the steady stream of stars that entertained them for 40 years. “I love the actors we have here; they are top quality,” Lamos told me in an interview for this article, noting that WCP is the only Connecticut theater that has been known principally for hiring stars. He takes pride in the excellence of the acting ensembles that WCP attracts and cited the 2014 revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s Things We Do For Love, with veteran Broadway director John Tillinger at the helm, as “some of the best ensemble comedy acting [by Geneva Carr, Matthew Greer, Sarah Manton, and Michael Mastro]I have ever seen anywhere, not just on this stage but anywhere. It was impeccable.”

Lamos says he is proudest of the shows that meet the Langner-Marshall standard, including WCP’s 2014 production of Nora, Ingmar Bergman’s reimagining of Ibsen’s classic A Doll’s House directed by associate artistic director David Kennedy. “Yes, there were chances that he took that didn’t necessarily pay off all the way but they were all so bold and interesting and I’m very proud of that production,” Lamos said, defending the production against some negative criticism. Among his own directorial work at WCP thus far, Lamos is most proud of his 2010 revival of the musical classic She Loves Me, which originally played on Broadway in 1963 starring Barbara Cook and Jack Cassidy. “It was a high-water mark for us, and when the team of writers—all masters of their craft—Sheldon Harnick, Jerry Bock, and Joe Masteroff, [agreed with that assessment]publicly at our symposium following a Sunday matinee, I was on cloud nine. ” Apparently, the Connecticut Critics Circle also agreed: that organization gave Lamos its 2010 award for outstanding director of a musical.

WCP still attracts the stars, particularly for its annual one-night-only fundraisers at which anyone from Bernadette Peters to Kristen Chenoweth to Patti LuPone is liable to show up, and is flourishing in the 21st century. WCP continues to solidify its role as a microcosm of the best the American stage has to offer during a period of maturation and growth.

Martha S. LoMonaco is the author of Summer Stock! An American Theatrical Phenomenon and is professor of theater and resident director at Fairfield University.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art and theater history and about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS pages.