By Fred Calabretta

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

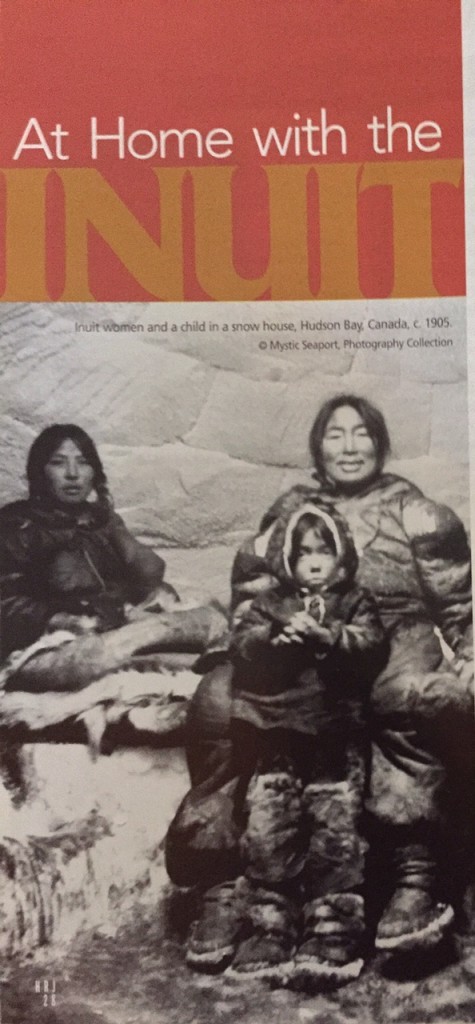

On March 10, 1905, sheltered within a wooden, snow-banked ship frozen solid into the Arctic ice, Captain George Comer recorded the morning’s temperature as minus 21 degrees Farenheit. He also noted that he had taken “a couple of pictures of the natives in their snow houses.” It was a typical day for the man who, though he called East Haddam home, had an abiding fascination with the Inuit, the Eastern Arctic’s “natives.”

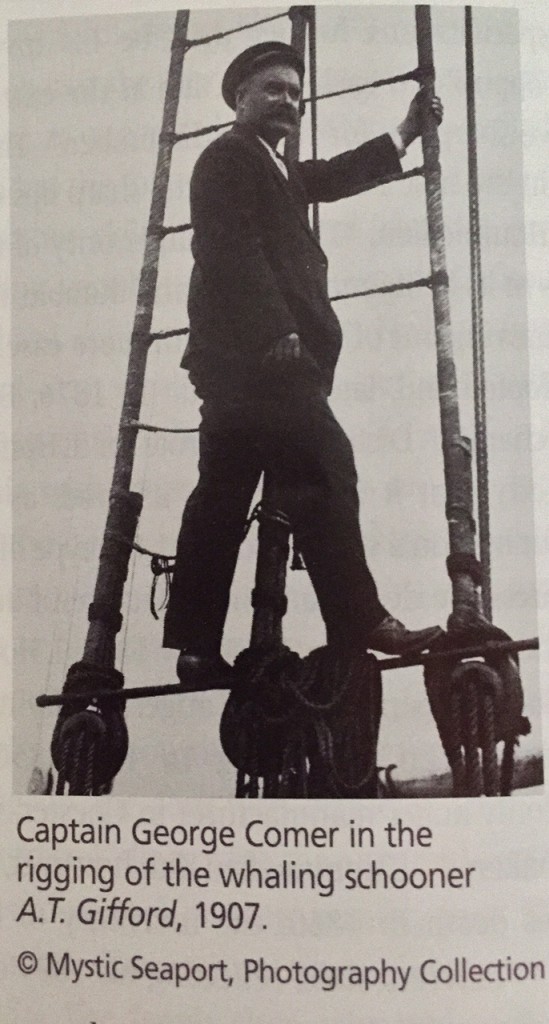

George Comer (1858-1937) overcame a childhood of hardship and adversity and found great success in dual, though complementary, careers. Drawn to the sea at age17, he thrived as a mariner and eventually became a captain, specializing in the Eastern Arctic whale fishery centered in Hudson Bay. Although his whaling activity occurred during the industry’s dying years, he managed to earn impressive profits for his ship’s owners. Remarkably, he also found additional success and made important contributions in the fields of science, exploration, and especially anthropology. Despite a limited education, Comer worked, socialized, and corresponded with many of the most prominent explorers, museum curators, and scientists of his time.

Several important relationships helped shape Comer’s character and legacy. Chief among them were his family, his association with the Inuit, and a 50-year connection with one of the world’s great museums. These relationships influenced his actions, accomplishments, and overall direction.

Comer’s family history and early years remain partially clouded in mystery. According to Comer himself, his parents emigrated from Great Britain and met and married in Quebec, where he was born in 1858. His father Thomas earned his living as a sailor and apparently disappeared on a voyage a year or two after George was born. For unknown reasons, his mother Johanna came to New England in the early 1860s. Massachusetts almshouse records show that she moved frequently, struggling to survive, with young George in tow. She worked as a washerwoman when her apparent poor health allowed. At some point in the mid-1860s Johanna arrived in Hartford. Finally failing in her attempts to support her son, she placed him in the Hartford Orphan Asylum (now the Village for Families and Children) where he remained for a few years and managed to obtain a limited education.

About 1869 the orphanage placed him with the Henry S. Ayer family on a farm in East Haddam, a picturesque country town nestled along the Connecticut River. The arrangement seems to have been some sort of indenture, and if so, would be among the last Connecticut examples of that once-common practice. Surviving records suggest that with the Ayers Comer finally experienced some sense of security. He had also met his future wife, Julia Chipman. A relative of the Ayer family, she had lost her father during the Civil War and was now also residing with them.

For unknown reasons, almost immediately after he turned 17, George walked to New London and shipped out on a whaler bound for the Arctic. His father had gone to sea, and perhaps the young man believed that by sharing that experience he would find some closeness to the parent he never knew. Whatever his motivation for his initial voyage, over the next 44 years he would venture from East Haddam many more times, setting sail on ships that often headed north.

The boy sailor kept a journal in 1875 while on his first voyage. This was unusual for someone of his age, and it established an important precedent. Today, in collections at Mystic Seaport Museum and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, nearly thirty Comer journals and notebooks survive. Rich in detail, they reflect in great depth the Captain’s thoughts and feelings and document his career, the whaling industry, natural history, the environment, geographical findings, and Inuit life and culture.

Comer married Julia not long after returning from his first voyage in 1878. He continued to go to sea, first on coastal vessels and then on demanding and dangerous seal-hunting voyages to the southern hemisphere. Comer met the challenges with success and moved up through the shipboard ranks.

Comer married Julia not long after returning from his first voyage in 1878. He continued to go to sea, first on coastal vessels and then on demanding and dangerous seal-hunting voyages to the southern hemisphere. Comer met the challenges with success and moved up through the shipboard ranks.

Between 1876 and 1919, Comer spent the equivalent of 23 years away from home. Before leaving on his voyages, he cut large quantities of firewood and made other provisions for his family’s comfort. While he was away, Comer wrote home often, expressing his love and affection for Julia and their children Thomas and Nellie. Despite the difficulties of separation, the children seem to have led relatively normal lives. Tom attended boarding school for a time and eventually worked on coastal steamboats. Eventually, Nellie and Tom both married. While long absences from family were a way of life for mariners, reunions themselves posed challenges. Older East Haddam residents recall that when at home, Comer ran his home somewhat like a ship and that Julia seemed uncomfortable around him.

Comer began to develop interests and skills unusual for a typical sailor. His seafaring life gave him wonderful opportunities to visit remote parts of the globe. Early in his career he demonstrated a fascination with the natural world and its people and an uncanny ability, especially for someone with a limited education, to document what he observed.

Beginning in the 1880s, Comer collected bird eggs and skeletons, which now rank among the earliest ornithological specimens in the collections of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. Throughout his travels far north and south of the equator in the 1880s and 1890s, he also collected minerals, plant specimens, and ethnographic objects and kept detailed written records of his observations. Comer’s whaling career reached a milestone when he first sailed as Captain in 1895. His career as an anthropologist was also gaining momentum.

During Comer’s very first voyage he had his initial contact with the native people of the Eastern Arctic. Commonly referred to as Eskimos, they are more accurately called Inuit, which, loosely translated, means “the people.” After that voyage, he did not return to the Arctic until 1889. Then, from that year until 1919, he made 13 voyages to the Arctic, developing an extraordinary relationship with the Inuit. The association became a defining element in his life.

American whalers and explorers of the Eastern Arctic had a long history of interaction with the Inuit, beginning in the 1840s. The Inuit were generally friendly and accommodating, sharing their knowledge of Arctic subsistence and survival. By the time Comer first sailed as captain the Inuit role in American whaling had become extensive and complex. The Inuit actively participated in whale hunting, often manning the whaleboats. This was a significant contribution, since the whaling industry had been in decline for decades, and skilled American whalemen were scarce.

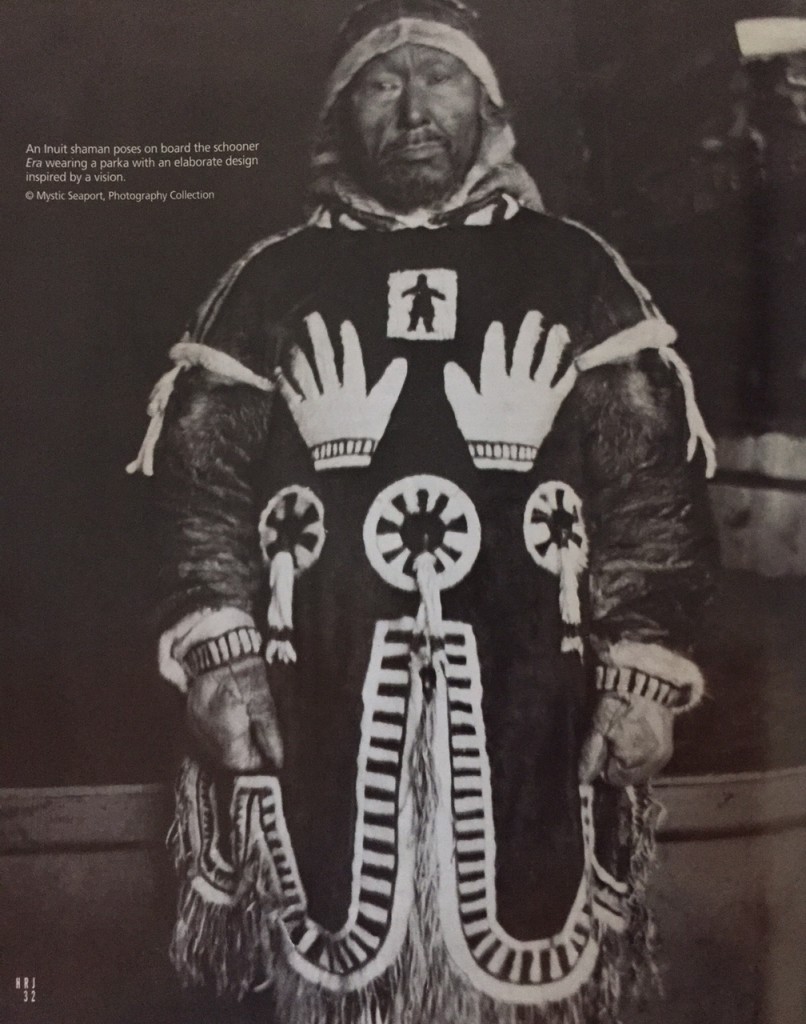

Most voyages included a deliberate stay of a winter or two, giving the whalers a head start for the spring whaling season. The wintering period, with the Inuit camped nearby, promoted extensive interaction and a mutual dependence between the two groups. The Inuit contributed to the whalers’ comfort and survival in many ways. They provided fresh meat and fish, which helped prevent scurvy, a potentially lethal disease. They also served as guides and assisted with travel.

While other captains interacted with the Inuit, George Comer’s relationship with them was unmatched in its depth and strength during his whaling period in Hudson Bay. The women sewed caribou-skin suits and sealskin boots for Comer and his entire crew. This clothing was more efficient than anything that could be brought from home and was necessary for winter survival. The importance of furs also extended far beyond their use for clothing. By the end of Comer’s career he had become a fur trader as much as a whaler, depending on fox, bear, wolf, and other furs obtained from the Inuit. Walrus and narwhal ivory also added to American returns. The whalers’ success, survival, and profits depended greatly on the Inuit.

In exchange for their assistance, goods, and services, the Inuit received trade goods Comer brought north. Inuit valued rifles, cartridges, knives, and cookware; the women prized fabric, ribbon, trims, and beads, which contributed to a burst of creative expression in clothing manufacture. Starvation was a frequent threat to Inuit survival, and during times when game was scarce, Comer provided the Inuit, whom he now considered his friends, with whatever preserved food he could spare. On frequent occasions, dozens of Inuit boarded Comer’s ship for meals.

Comer’s relationship with the Inuit was much more than a business arrangement. He possessed a genuine compassion for these people and worried about their hardships and difficult lives. He respected, admired, and cared about them. His feelings toward them were remarkable for their time, and a crewmember of another whaleship once referred to him as “native crazy.”

The whaling season lasted roughly from mid-May to mid-September, and the remainder of the year was spent preparing for or living in winter quarters. The ship was placed in a protected harbor; by October, ice began to form around it, actually keeping the ship safe and secure. By spring the ice could be as much as six feet thick. The wintering period required little whaling activity or ship maintenance, thus providing time for extended interaction with the Inuit.

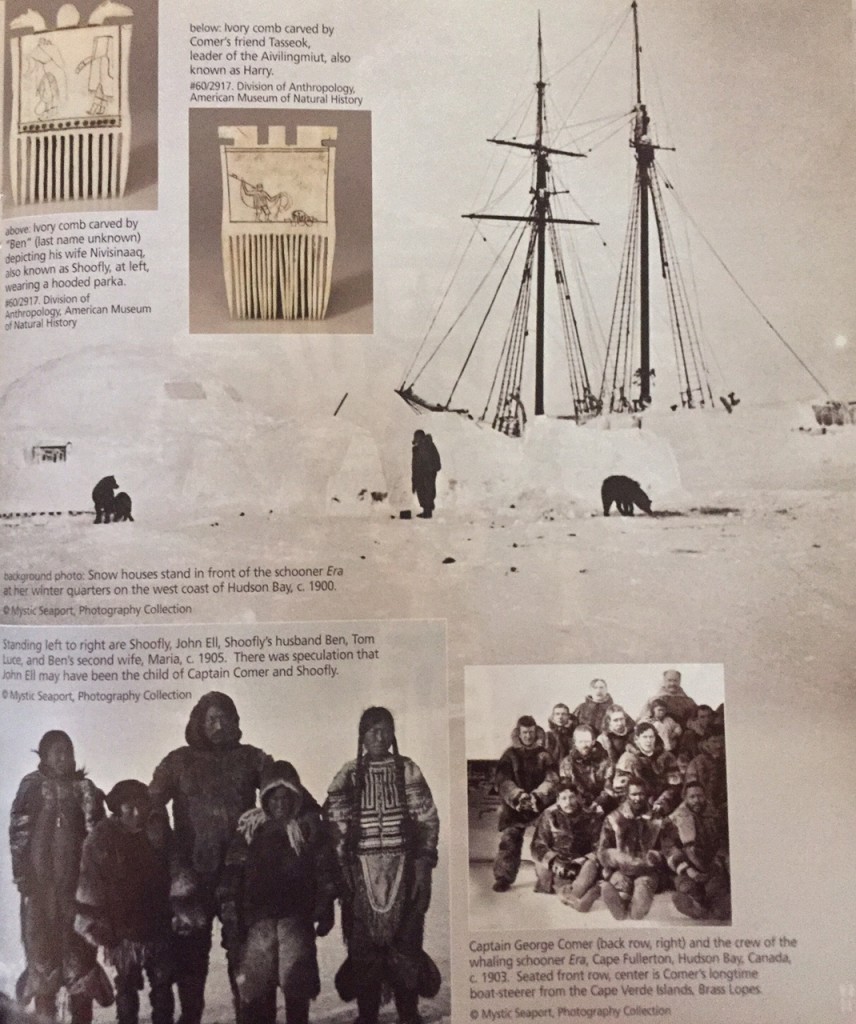

During the long periods of close contact Comer formed strong bonds with individual Inuit. He came to greatly admire one named Tasseok, known by the whalers as Harry. He was the highly respected leader of the Aivilingmiut, the Inuit group Comer worked most closely with, and was a skilled hunter and carver of ivory. Comer also became very close to an Inuit woman known as Nivisinaaq, named “Shoofly” by the whalers after a popular song of the time. She became Comer’s companion and apparently lived with him for extended periods of time on his ship. She is remembered among today’s Inuit as Shoofly Comer. Shoofly was married to Ben, an Inuit man who was also a good friend of Comer and who once saved his life when the Captain fell through the ice. Although their relationship may seem controversial by contemporary standards, it was culturally acceptable among the Inuit provided it was in the open and all involved parties were agreeable to the arrangement.

It is interesting to consider if Julia Comer or her children knew of George’s relationship with Shoofly. There were certainly clues. Comer kept a number of Inuit objects in his home, including several made by Shoofly. One of these was a beaded belt, still owned by Comer descendents, which features the names Shoofly and John Ell in beadwork. There is some speculation and differing opinion regarding the possibility that Comer and Shoofly had one or more children together. John Ell may have been their child, although he was more likely adopted by Shoofly and became a favorite of the Captain. Long after he retired from the sea, Comer continued to send money and gifts to Shoofly and John Ell, which may also have aroused Julia’s curiosity about the nature of their relationship.

Comer’s relationship with the Inuit ultimately culminated in his most important life’s work. By 1895, he began to collect substantial quantities of Inuit objects and bring them home. In 1897, he was contacted by a man who expressed considerable interest in these collections. Seeking information about the Inuit, Franz Boas had contacted a mentor of Comer’s, Captain John O. Spicer of Groton, Connecticut. Spicer referred Boas to Captain Comer. This connection united two men who would work together for many years, sharing a commitment to documenting Inuit culture and life ways.

Boas is one of the most notable figures of his era and ranks as the father of modern anthropology. His accomplishments include a teaching career that provided important training to Margaret Mead, Alfred Kroeber, and many other prominent 20th-century anthropologists. At the time Boas contacted Comer he had recently accepted an important curatorial position in the anthropology department at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Boas arranged for the purchase of Comer’s small Inuit collection for the American Museum, and in doing so established a 40-year relationship between the Captain and the great institution. Boas then took a step that truly launched the Captain’s anthropological career. Comer was preparing to sail in June 1897 on a whaling voyage to Hudson Bay. Boas asked Comer to collect for the American Museum and offered to pay generously for his work. Comer eagerly accepted. Two years later Comer returned. Boas was dazzled with what he had brought back and noted to a colleague “The collection must be considered an exceptionally valuable acquisition.”

Boas arranged for Comer to assemble additional, and even more comprehensive, collections for the American Museum of Natural History. Comer not only brought back thousands of objects, he made detailed written records of Inuit life, made dozens of sound recordings, took hundreds of photographs, and even made plaster life masks of Inuit faces. The photos, life masks, and sound recordings were among the first ever obtained among the native people of Arctic Canada.

Comer frequently visited the American Museum of Natural History, assisting with Arctic exhibits or other projects. By about 1910 the Museum could boast that it had the finest Arctic holdings in the world. Boas published two books based in large part on Comer’s fieldwork, giving the Captain the credit he deserved. Comer maintained his associations with Boas and the museum and added to his credentials by doing pioneering archaeological work in Greenland during an expedition from 1915 to 1917.

Comer made one final, ill-fated voyage to Hudson Bay in 1919. Assisting ethnologist Christian Leden on a research and commercial trip, their schooner Finback was wrecked when it struck rocks. Comer and crew survived and safely made their way home. Although the trip was a failure, Comer had succeeded in visiting his Inuit friends one last time.

Settling back home, Comer became a celebrity in Connecticut, regaling visitors with stories of the North. He served a term in the state legislature and was often called upon to give talks to groups. He illustrated these with lantern slides prepared from his Arctic photographs. He continued to correspond with prominent scholars, museum officials, and Arctic explorers and had occasional contact with Boas.

During the last years of his life Comer also maintained his fondness for the American Museum of Natural History and its staff. In a 1925 letter to its director, he clearly expressed this sentiment, stating, “My life has been made brighter and my vision of life broadened by coming in contact with the Museum and its people.” He provided his museum friends with gifts from the East Haddam countryside, occasionally sending pussywillows or apples to the secretaries and prominent curators such as Clark Wissler and Robert Cushman Murphy.

George Comer died of Bright’s Disease, a form of kidney disease, in 1937. His passing was noted in New York and Connecticut newspapers. As a tribute and gesture of remembrance, a year later the State of Connecticut dedicated a small park and monument in his honor near his home in East Haddam. Twenty years after he had acquired his final specimens for the American Museum of Natural History, staff members contributed to his memorial. Several attended the 1938 monument dedication, as did the daughter of Robert Peary (the Arctic explorer who was the first man to reach the North Pole). Comer would have undoubtedly appreciated this final recognition from family and museum people—two groups that had meant so much to him. Only the Inuit were missing, but they would come later.

In 1999, two women from Hudson Bay came to Mystic Seaport to study the Comer collections there and to meet with Captain Comer’s great-grandson Thomas Comer and other Comer family members. The Inuit women had a special interest in the meeting. Bernadette Dean and Rhoda Karetak, are, respectively, the great-granddaughter and granddaughter of Shoofly, Captain Comer’s long-time companion. Although they likely are not blood relatives, Bernadette Dean and Tom Comer have formed a strong relationship and share a common heritage. Comer spent years in the territory of the Inuit and his life and legacy came full circle when, nearly 100 years later, Bernadette Dean visited his monument and grave.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut’s Maritime History on our TOPICS page.