By Alan Bisbort

(c) Connecticut Explored, Winter 2015-2016

Shop/Buy the Issue!

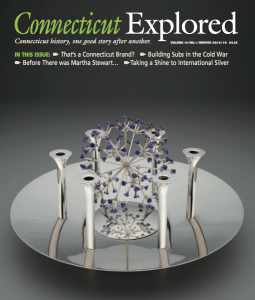

Some companies have been tested by fire, some by the vagaries of the market or changes in technology, but the Bigelow tea company in Fairfield was tested by water. Lots and lots of water.

Now a third-generation family-owned and family-run business, officially known as R.C. Bigelow, Inc., the company was started in 1945 by Ruth Campbell Bigelow and her husband David E. Bigelow, Sr. as a cottage industry out of their four-floor brownstone at 241 East 60th Street in Manhattan. Since its move to in Norwalk in 1950 and a watery baptism there in the Flood of 1955, the company has sustained 65 solid years of constant positive comments in Connecticut. 2015 marks the company’s 70th anniversary.

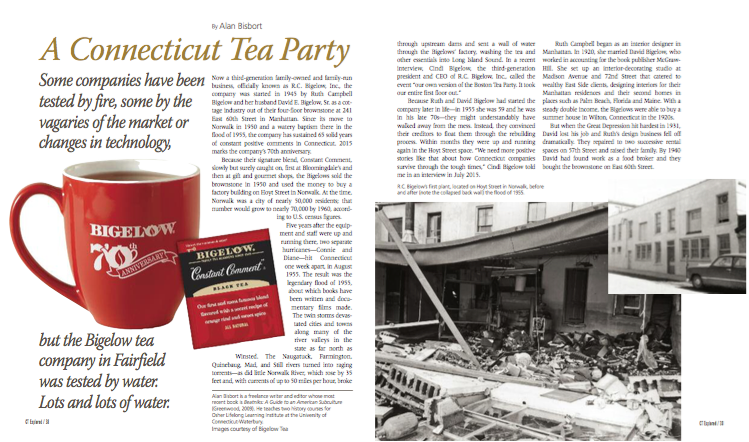

Because their signature blend, Constant Comment, slowly but surely caught on, first at Bloomingdale’s and then at gift and gourmet shops, the Bigelows sold the brownstone in 1950 and used the money to buy a factory building on Hoyt Street in Norwalk. At the time, Norwalk was a city of nearly 50,000 residents; that number would grow to nearly 70,000 by 1960, according to U.S. census figures.

Five years after the equipment and staff were up and running there, two separate hurricanes—Connie and Diane—hit Connecticut one week apart, in August 1955. The result was the legendary flood of 1955, about which books have been written and documentary films made. The twin storms devastated cities and towns along many of the river valleys in the state as far north as Winsted. The Naugatuck, Farmington, Quinebaug, Mad, and Still rivers turned into raging torrents—as did little Norwalk River, which rose by 35 feet and, with currents of up to 50 miles per hour, broke through upstream dams and sent a wall of water through the Bigelows’ factory, washing the tea and other essentials into Long Island Sound. In a recent interview, Cindi Bigelow, the third-generation president and CEO of R.C. Bigelow, Inc., called the event “our own version of the Boston Tea Party. It took our entire first floor out.”

Because Ruth and David Bigelow had started the company later in life—in 1955, she was 59 and he was in his late 70s—they might understandably have walked away from the mess. Instead, they convinced their creditors to float them through the rebuilding process. Within months they were up and running again in the Hoyt Street space. “We need more positive stories like that about how Connecticut companies survive through the tough times,” Cindi Bigelow told me in an interview in July 2015.

Because Ruth and David Bigelow had started the company later in life—in 1955, she was 59 and he was in his late 70s—they might understandably have walked away from the mess. Instead, they convinced their creditors to float them through the rebuilding process. Within months they were up and running again in the Hoyt Street space. “We need more positive stories like that about how Connecticut companies survive through the tough times,” Cindi Bigelow told me in an interview in July 2015.

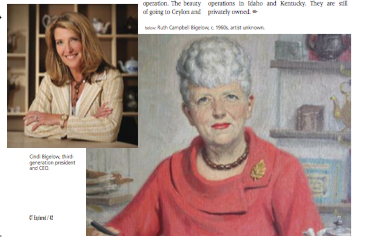

Ruth Campbell began as an interior designer in Manhattan. In 1920, she married David Bigelow, who worked in accounting for the book publisher McGraw-Hill. She set up an interior-decorating studio at Madison Avenue and 72nd Street that catered to wealthy East Side clients, designing interiors for their Manhattan residences and their second homes in places such as Palm Beach and Maine. With a steady double income, the Bigelows were able to buy a summer house in Wilton, Connecticut in the 1920s.

However, when the Great Depression hit hardest in 1931, David lost his job and Ruth’s design business fell off dramatically. They repaired to two successive rental spaces on 57th Street and raised their family. By 1940 David had found work as a food broker and they bought the brownstone on East 60th Street.

“During the Depression, my grandmother took copious notes about how to start a business that everyone in the family could work in,” Cindi Bigelow told me. Putting her notes into practice, she and David established Wilton House Foods out of their brownstone and began distributing Chinese seasonings that they blended and packaged at night and sold to Canal Street businesses during the day. With this income—$3,000 a month, by their son David’s estimate—they were able to stay afloat and raise their family. Buoyed by this modest success, Ruth set her sight on other food products, including tea.

“Tea was a good option because there just wasn’t much available in the U.S. beyond basic bland black tea,” said Cindi Bigelow. “Grandmother had gone to England a number of times and knew what a good cup of tea was supposed to taste like.” On a tip from her friend and design colleague Bertha Nealey, Ruth got hold of an old colonial American recipe and modified it a bit to develop the Constant Comment blend.

A May 1945 profile in The New York Times by Jane Holt noted, “Ruth Campbell Bigelow and Bertha West Nealey are both interior decorators whose enthusiasm for tea has led them to blend their own…[it’s] an unusual and delicious brew called Constant Comment.” In a July 1945 article for the New York Herald Tribune, Clementine Paddleford, a legendary food journalist who would go on to write the landmark book How America Eats (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1960), described how the name was chosen for the now-iconic blend: “One of Mrs. Bigelow’s Park Avenue friends was giving an afternoon party, and it was suggested she try the new blend. Not a word was said to the guest regarding its novelty, yet everyone spoke of the tea’s aroma, its flavor—there was ‘constant comment.’ A good name, why not? Labels were made and the tea was hurried to the stores where it is selling at around 75 cents for the two-and-one-quarter ounce jar. Expensive? But here’s a tea so flavorful that three-quarters of a teaspoon make six bracing cups of aromatic spiciness.”

A May 1945 profile in The New York Times by Jane Holt noted, “Ruth Campbell Bigelow and Bertha West Nealey are both interior decorators whose enthusiasm for tea has led them to blend their own…[it’s] an unusual and delicious brew called Constant Comment.” In a July 1945 article for the New York Herald Tribune, Clementine Paddleford, a legendary food journalist who would go on to write the landmark book How America Eats (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1960), described how the name was chosen for the now-iconic blend: “One of Mrs. Bigelow’s Park Avenue friends was giving an afternoon party, and it was suggested she try the new blend. Not a word was said to the guest regarding its novelty, yet everyone spoke of the tea’s aroma, its flavor—there was ‘constant comment.’ A good name, why not? Labels were made and the tea was hurried to the stores where it is selling at around 75 cents for the two-and-one-quarter ounce jar. Expensive? But here’s a tea so flavorful that three-quarters of a teaspoon make six bracing cups of aromatic spiciness.”

Constant Comment was at first sold as loose tea in tins on which Ruth and David Sr. and David Jr.—by then, Ruth and David Sr.’s son was a Yale University graduate, class of 1948—hand-painted the labels. Ruth’s powers of persuasion got her product on the shelves at Bloomingdale’s, a connection that was used in ads to widen the market, according to her son David. She hand-lettered postcards promoting the tea and sent them to socialites. But the company had hit a wall in its efforts to break out beyond New York City.

According to International Directory of Company Histories (St. James Press, 2003), a customer asked if she could smell the tea. She was so impressed that she bought a jar, and later returned to buy more. This gave Ruth the idea to create the “whiffing jar,” which was included with every bulk order. Gift shops in New England were particularly smitten by this interactive way for shoppers to smell the then-exotic aroma of Constant Comment. By 1950, Constant Comment was finding its way into everything from gift shops to hardware stores—but it still could not be found on grocery-store shelves.

Still, the product was successful enough that in 1950, the Bigelows sold their brownstone and relocated the business to Norwalk, while living in their summer house in nearby Wilton. More change followed. They hired a West Coast salesman that year, a move that was met with great success. In 1957 the company moved into a larger plant in Norwalk and bought its first tea-bag machine—transitioning from producing tins of loose tea to packaging tea in convenient single-serving bags. Grocery stores began to receive requests from customers, and, with the aid of food brokers, by the end of the 1960s the company had more accounts from grocery stores than from specialty shops.

They began marketing other specialty teas, too. One of the most successful of this first wave was Plantation Mint, still a big seller for the company. Eunice Bigelow, Ruth’s daughter-in-law and Cindi’s mother, was responsible for this blend.

“My grandmother did not like spearmint and always used peppermint in her tea recipes,” Cindi Bigelow told me. “But my mother didn’t like peppermint, so she kind of went behind my grandmother’s back and created what would become Plantation Mint with black tea and natural spearmint.”

According to the Bigelow website, Eunice Bigelow recalled, “My husband and I went behind closed doors and started experimenting.… We tried tea after tea to find the perfect combination. Then we set out to find a spearmint grown in America…we fell in love with one from a farm out west.” When it came time to show this new blend to her mother in law, Eunice admitted being “nervous,” so David Jr. devised a plan. They gift-wrapped a box of the tea and gave it to Ruth on Mother’s Day 1957. Eunice recalled, “She gave us a funny look and then decided to try it…and she loved it.”

In 1963, David Jr. and Eunice took the company helm and steered it into the modern grocery-store market by introducing a large number of now popular flavored teas and the individually foil-wrapped tea bags. Ruth died in 1966 at age 70 and David Sr. in 1970. In 2005, David and Eunice became co-chairs of the company’s board of directors and daughter Cindi took over as third-generation president and CEO. Her sister Lori Bigelow works on product development.

R.C. Bigelow, Inc. has in recent years aimed to keep the traditions and history associated with tea alive. In 2003 the company purchased the Charleston Tea Plantation on Wadmalaw Island in South Carolina from the Thomas J. Lipton Company, and is restoring its 127 acres of tea plants (Camellia sinensis). A visitor center on site that documents the history of growing, harvesting, and withering tea attracts 60,000 people a year, and guides offer trolley tours of the gardens.

“There were very few tea plantations in the United States to begin with, and we now have the only working tea estate in the country,” said Cindi Bigelow in our interview. “Lipton started it in 1960 and kept a test lab there.” The tea grown there is used for a local brand called Charleston Tea, or American Classic Tea.

“For products with the Bigelow name on the package, though, the company only uses high-mountain-grown, handpicked tea from Sri Lanka and India—the same tea that Ruth used. We are the number one importer of Ceylon tea from Sri Lanka,” said Bigelow. “We also buy from tea growers in India, from plantations in Darjeeling. We have used the same gardens there for 40 or 50 years, which are overseen by the same family. Like our company, it’s a multigenerational operation. The beauty of going to Ceylon and India is that the growers are dedicated to growing the best tea and their base of knowledge is irreplaceable. They are amazingly passionate about tea…. We stick with what got us to where we are today.”

While continuing to operate out of factory space on Hoyt Street and Merwin Street in Norwalk, R.C. Bigelow, Inc. kept warehouse space in nearby Fairfield. In 1990 the company built a 100,000-square-foot building on the site of its old warehouse, at 201 Black Rock Turnpike in Fairfield.

Today R.C. Bigelow, Inc. sells 1.7 billion tea bags annually in 130 varieties, including flavored, green, organic, and herbal, with new blends added occasionally, including some based on Girl Scout cookie flavors. The Fairfield factory, where 10 machines operate 20 hours a day, each making 100 tea bags a minute, produces 20,000 tons of tea a day, or 1.7 billion tea bags annually. With annual sales of $150 million, R.C. Bigelow, Inc. has 24 percent of the specialty-tea market, according to company statistics. The main operations of the company are still based in Fairfield, with adjunct distribution and manufacturing operations in Idaho and Kentucky. They are still privately owned.

Today R.C. Bigelow, Inc. sells 1.7 billion tea bags annually in 130 varieties, including flavored, green, organic, and herbal, with new blends added occasionally, including some based on Girl Scout cookie flavors. The Fairfield factory, where 10 machines operate 20 hours a day, each making 100 tea bags a minute, produces 20,000 tons of tea a day, or 1.7 billion tea bags annually. With annual sales of $150 million, R.C. Bigelow, Inc. has 24 percent of the specialty-tea market, according to company statistics. The main operations of the company are still based in Fairfield, with adjunct distribution and manufacturing operations in Idaho and Kentucky. They are still privately owned.

Alan Bisbort is a freelance writer and editor whose most recent book is Beatniks: A Guide to an American Subculture (Greenwood). He teaches two history courses for Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at the University of Connecticut-Waterbury.

Explore!

Read more about products Made in Connecticut and Connecticut’s Food History on our TOPICs pages.