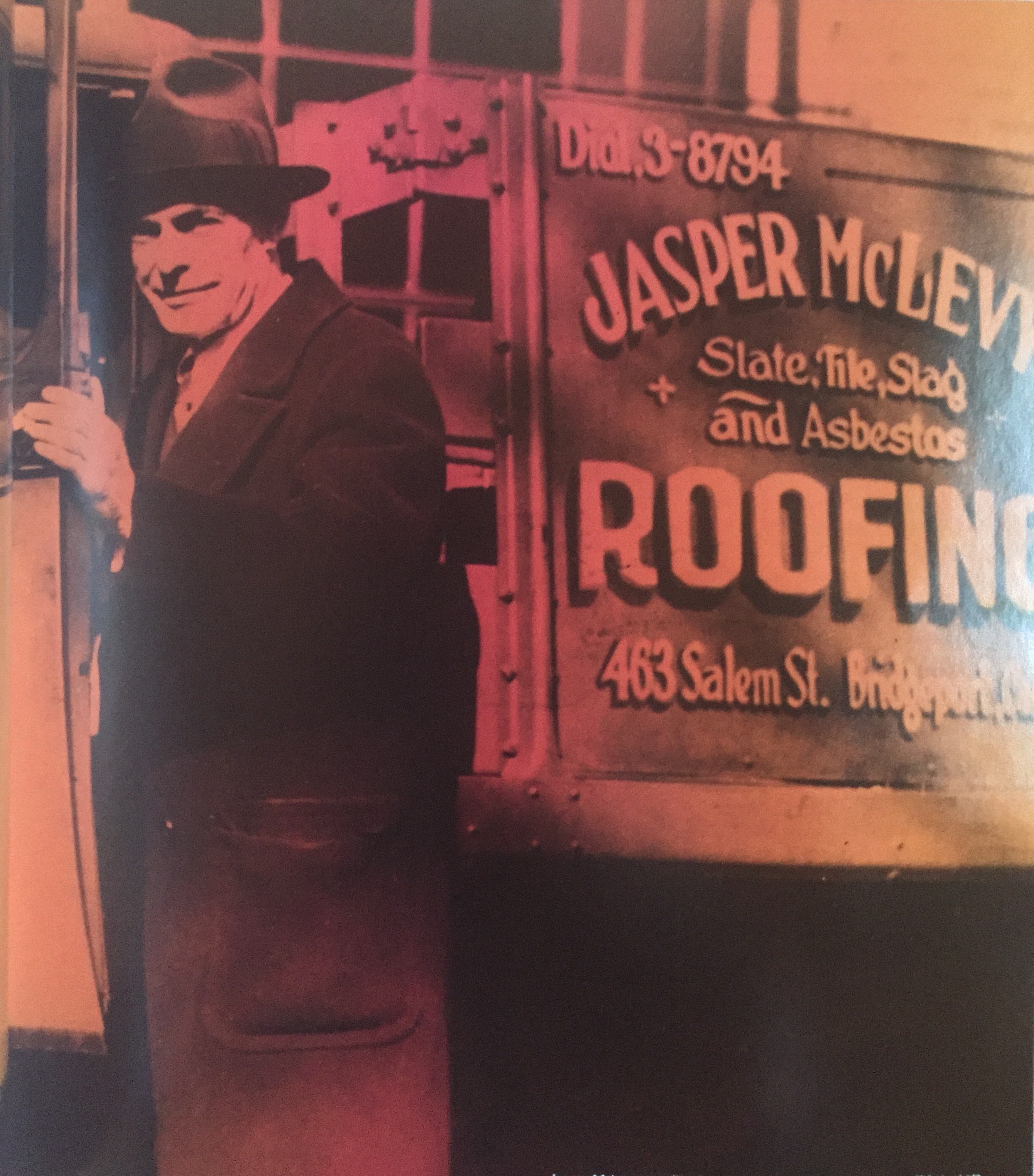

Jasper McLevy standing by his roofing truck, 1933. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

By Mary Witkowski

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

(All photos courtesy of the Bridgeport Historical Center, Bridgeport Public Library)

The man standing on a soapbox looked earnest. He was tall and dark haired and had a wiry physique; his face reminded people of Abraham Lincoln’s. He was running for mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1933, broadcasting his campaign speech via a loudspeaker hooked to a roofing truck. This unusual sight may have been amusing to some in the audience, but the direct, honest intent of the man, Jasper McLevy, had started to capture the imagination of Bridgeport’s voting public.

McLevy and his trademark roofing truck were no strangers to the Bridgeport public. He had been sponsored by the Socialist Party since 1911. According to a 1936 article by Bridgeport Life reporter Robert M. Sperry, “Mr. McLevy spoke on street corners and exposed crookedness in both major parties.” At the time of his campaign in 1933, the two major parties were Democrat and Republican. Perry wrote, “the affairs of city government went from two political machines to a double political machine.” Perry also noted, “Boss Tweed in his most crooked days was a piker in comparison with the political parties sacking Bridgeport.” (Boss Tweed was the famous New York City political boss of the 19th century.)

In Bridgeport the two decades before 1933 had been marked with economic ups and downs. The manufacturing boom at the turn of the century fueled Bridgeport’s growth as new industries (with hundreds of factories – including Remington Arms, Singer, and General Electric — manufacturing everything from cars and corsets to sewing machines and firearms) and large numbers of immigrant workers arrived in the city. World War I had been similarly kind to the city.

But things were grim across the country in 1933, and the Depression had hit Bridgeport hard. People stood in lines looking for work and food. Crowds of unemployed people camped outside municipal buildings waiting for assistance for themselves and their families. But there were no jobs. Labor strikes had become commonplace, and labor unions became increasingly active in asserting workers’ rights.

According to David Palmquist in A Pictorial History of Bridgeport, Bridgeport’s mayor from 1911 to 1921, Republican Clifford Wilson, was a progressive reformer who tried to address the city’s major problems such as the housing shortage and accommodating the rapid influx of immigrants. Palmquist notes that Wilson tried to modernize the city, hiring a Boston designer to lay out a blueprint for Bridgeport’s future. But in 1925, the State of Connecticut took over Bridgeport’s finances and tax collection when the city had failed to collect taxes going back ten or fifteen years, a problem Wilson inherited from previous administrations.

When Mayor Wilson left office in 1921, Bridgeport went into an economic slump. Overcrowded schools, loss of merchants, and general malaise battered the city. Democrat Fred Atwater served as mayor from 1921 to 1923, and Republican F. William Behrens, Jr. served from 1923 to 1929.

Edward Buckingham, a Democrat, was elected mayor in 1929, having served in that role before, from 1909 to 1911. Buckingham found himself leading a city that, with no money or jobs, faced a bleak future. Buckingham built Yellow Mill Bridge, which cost the taxpayers $280,000 at a time when resources were exceedingly scarce. Bridgeport City Hall was in turmoil. City employees were angry at the mayor and his administration. Even as Buckingham slashed the wages of city workers, he continued to drive a fancy Pierce-Arrow, considered to be an extravagant car. The negative atmosphere resounded throughout the city.

Voters had an important decision to make. Should they vote for the Democrat who got them into this mess? Would the Republicans of the previous administration be a better choice? Could Jasper McLevy, a roofer, solve the problems of the city?

Becoming Mayor

Jasper McLevy worked for the family business beginning at age 14. He and his brothers worked with their Scottish immigrant father George, who taught them the art of installing slate roofs, a skill he had learned in Scotland.

According to immigration records, Jasper McLevy’s parents, George and Mary Ann, left Glasgow, Scotland in February 1866. The McLevy family settled on Warren Street in the south end of Bridgeport. Their neighbors were working-class people, most of them immigrants. Nearby factories such as Harvey Hubbell’s electrical components-manufacturing plant, the Warner Brothers Corset Manufacturers and Underwood (which made typewriters) provided employment for many, while the family roofing business kept Jasper, his father, and his brother busy. Jasper’s sister Maude worked in a factory, while another sister Mabel worked as a teacher.

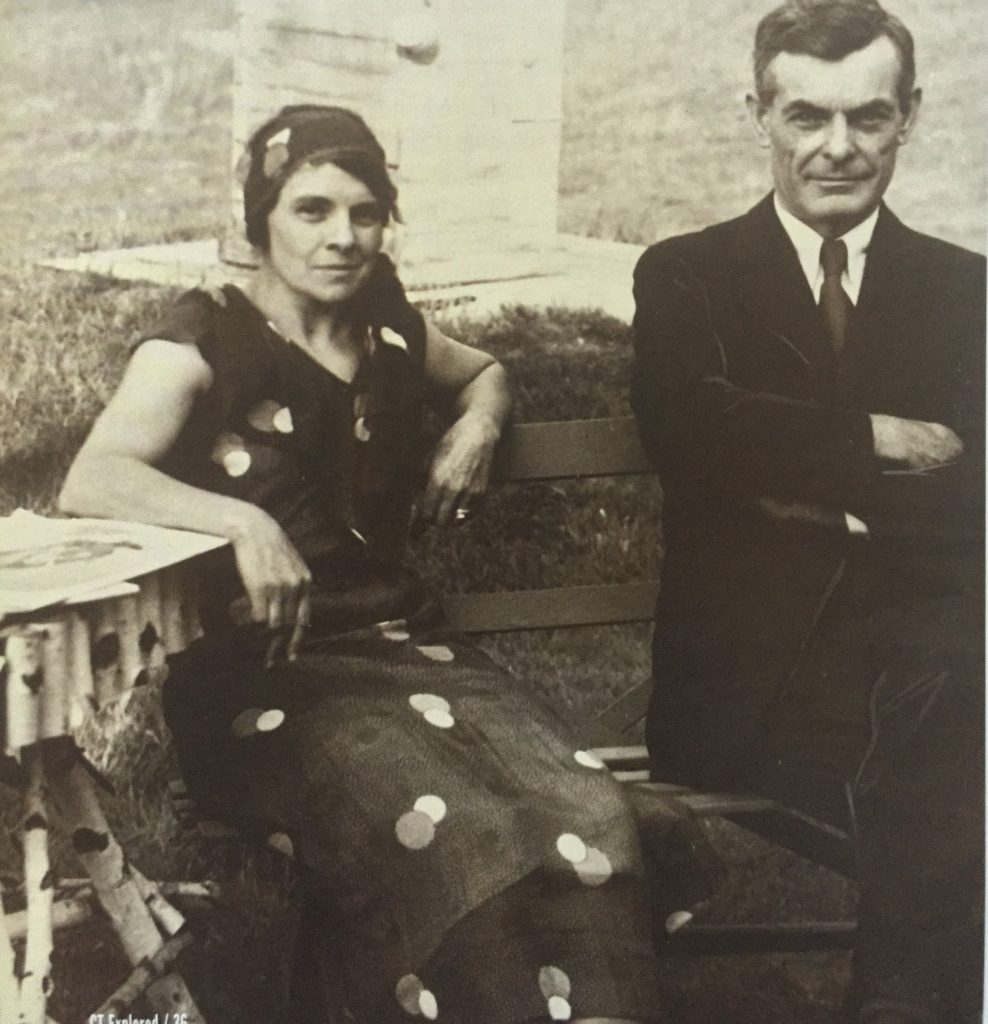

Vida Stearns McLeavy and Jasper McLevy at the Stearns Farm in Washington, Connecticut, May 21, 1934. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Seaside Park, a landscape of rolling fields of green grass and trees on Long Island Sound, was within walking distance of the McLevy home, and the Prospect School, where Jasper attended grade school, was about two blocks away. Young Jasper spent lots of time in the park playing baseball, a sport he enjoyed his whole life.

When McLevy was nine, his father died after falling from a roof he was working on. His death forced young Jasper to grow up quickly. He and his brothers worked with their uncle to maintain the family roofing business. McLevy helped to care for his widowed mother and the rest of the family.

Yet McLevy still was a boy at heart. Not long after his father’s death, he was caught sneaking into the circus then located in the City’s west end. The circus was owned by Bridgeport resident P.T. Barnum, who lived near Seaside Park and owned the winter quarters for the circus. As the Bridgeport Herald reported on November 10, 1957 (and McLevy himself often recalled himself), “when P.T. Barnum himself grabbed little Jasper by the seat of his pants” and “gave him a lecture on Honesty, a lesson which McLevy obviously never forgot.”

When McLevy was in his teens, he became interested in socialism after reading Edward Bellamy’s 1889 book Looking Backward. That book opened his eyes to the prospect of an ideal future world filled with peace and love. In 1938, McLevy recalled later to the writer Webb Waldon, “it was the most important book he had ever read in its influence on him.”

In 1900, when McLevy was 22, he joined the Socialist Party. He made friends with Edwin Stearns, a German immigrant who moved to Bridgeport in 1899, and opened a billiards hall. Stearns had become a socialist in 1869, just before he immigrated. His interest in socialism led him to create the first English-speaking socialist party in Bridgeport. Stearn’s billiards parlor became the first headquarters of the Bridgeport Socialist Party.

Stearns and McLevy attended meetings of the Bridgeport board of aldermen, and both men occasionally ran for local offices. The Bridgeport Sunday Herald of 1962 reported that between 1903 and 1933, McLevy had run—unsuccessfully—as a socialist for city clerk, state senator, and mayor.

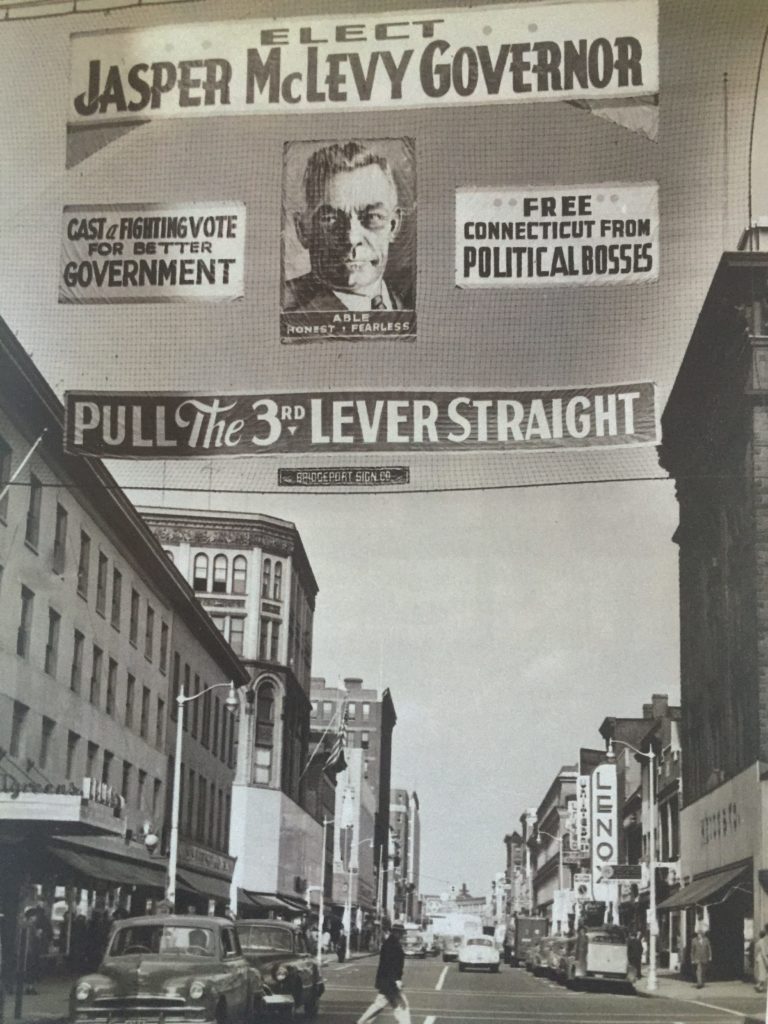

McLevy’s campaign banner hanging over Main Street, Bridgeport, 1938. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Though McLevy continued to live with his mother, he married a young woman named Mary Flynn, but she died two years into their marriage. Little else is known about that time in his life. In 1911, McLevy campaigned for mayor for the first time. Throughout his political career, as the Sunday Herald noted, “his soap box appeal of good government and an aging bankrupt city has called him forth as its savior from political corruption.” McLevy kept an American flag close at hand, knowing that the sight of that familiar symbol would assure the voting public that this socialist was an honest American.

In a 1999 oral history, Sam Liskov, whose brother Kieve had worked with McLevy when he first became mayor, recalled the sight of McLevy campaigning. “He [Kieve] put a high powered loud speaker system in an old Model A Ford that we used for the store.” The Liskov brothers owned a radio store just a block away from Workman’s Circle Hall, the socialist headquarters on Hudson Street. “We would go up and down Main Street campaigning for Jasper.”

Despite the Socialist Party’s being unfamiliar to much of Bridgeport’s electorate, municipal government unrest, political corruption, and the Great Depression made McLevy an attractive alternative to the status quo.

Jasper McLevy, the slate roofer, took on a city riddled with problems, and he was ready.

The Sunday Herald on November 10, 1957 reported, “Edward Buckingham, a currently popular, immensely self assured man, read the election returns; Buckingham 17,889 votes, McLevy 15,084. The handwriting was inscribed on the walls of City Hall, clearly legible for all who cared to read: Jasper McLevy will be the next Mayor of Bridgeport.” The year was 1932.

Mayor McLevy

“He was a master. Really a man with a limited education but tremendously astute and always told everything exactly as it was. I don’t think the man ever told a lie in his life. He was incapable of it.” – Bridgeport businessman Robert Factor in a 1999 oral history

According to the Bridgeport Herald, when Mayor Jasper McLevy took office on November 13, 1933, the number of unemployed had multiplied and the number of families on welfare in Bridgeport jumped to more than 490 persons a day.

Ten days after McLevy’s election, Cannon Street between Main and Broad became the site of a near riot according to the Bridgeport Post (November 23, 1933), as men crowded around the State Free Employment Bureau. Nearly 2,000 jobs were to be made available in Bridgeport under the federal Civil Works Administration as part of Roosevelt’s New deal programs. Mayor McLevy had worked with other city officials to help move hundreds of men in Bridgeport who were receiving welfare into the new jobs provided by the federal government. Men began standing in line at the employment bureau before 7 a.m., some arriving before dawn. Sixteen Bridgeport policemen were on hand to ensure that the large crowd remained calm.

By 1 p.m. that day, more than 1,000 applicants were enrolled in the work program, though the crowd was restive. Rules established by the state said men with families would be first in line for jobs. Women and single men would be allowed to sign up later in the week. But several times during the day, the men outside the office got angry and tried to force the doors of the employment bureau.

Unskilled labor would earn 50 cents an hour and skilled labor as much as $1.20 an hour. Typical jobs included working on school buildings, parks, and roads, demolishing old buildings, additions to buildings, bridges, and repairing the seawall at Seaside Park.

By 1935, Roosevelt’s administration started new work-relief programs that were administered by the Works Progress Administration. Bridgeport took advantage of the relief money and poured it into projects throughout the city, using federal money to pay for everything from maintenance of public buildings to sewer systems. WPA workers helped build the municipal airport. The Civil Works Administration set up offices in the old South End Library, a fire house, the Methodist Church, and the Barnum Institute.

Troubles for McLevy

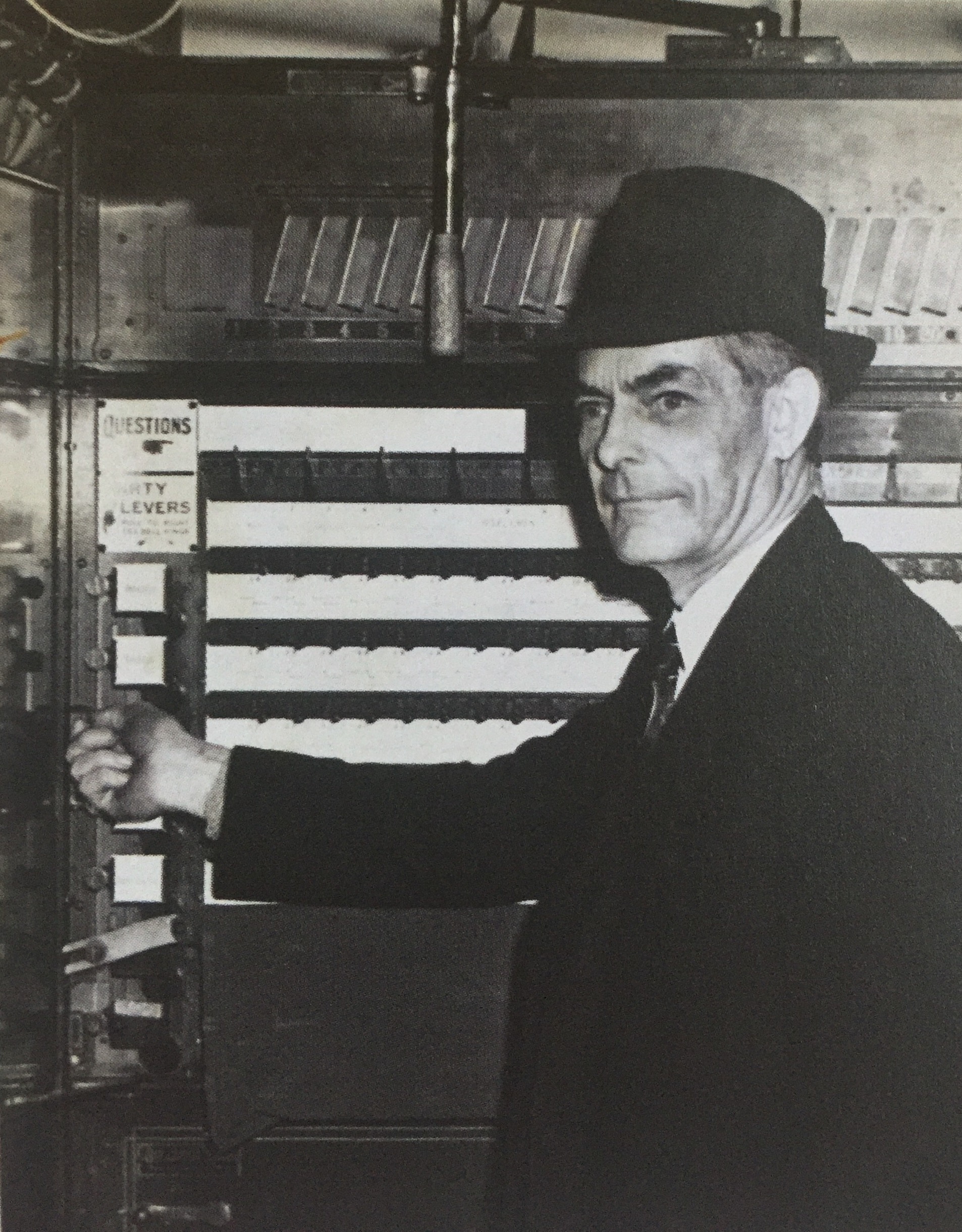

Jasper McLevy voting in the 1939 election, November 7, 1939. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Despite his successes at using such resources to help put city residents to work, McLevy’s tenure as mayor was marked by its share of problems. In 1934, a fierce blizzard blanketed Bridgeport with more than 20 inches of snow, sparking a controversy over whether McLevy’s administration had budgeted sufficient funds for snow removal. (Legend has it that McLevy responded to critics by saying, “God put the snow there, let him take it away.”) And when Bridgeport celebrated its centennial in 1936, the German zeppelin Hindenburg flew over the city. As part of the celebrations, Mayor McLevy sent a radiogram to the zeppelin’s commander, Hugo Eckner. Even members of his own party protested McLevy’s decision to communicate with the Germans.

But the real shocker of McLevy’s career came on May 20, 1934, when the Bridgeport Herald featured the headline “Jasper Secretly Wed.” This was big news: Bridgeport’s new mayor had kept his marriage to Vida Stearns secret for almost five years!

The front page of the Herald had a photograph of the Delaware marriage certificate that showed Jasper McLevy and Vida Stearns had been married in Wilmington on December 10, 1929. Photographs that later appeared in local newspapers showed a smiling Vida Stearns and McLevy, dressed in casual clothing, photographed in the Stearns family farmhouse in Washington, Connecticut.

Although the Bridgeport Herald had reported the story first, the Bridgeport Post was quick to send a reporter to get an interview with the McLevys. Vida explained that their marriage had been kept secret “for more than five years because she desired to continue keeping house for her father Edwin Stearns who was 87 years old.” Mayor McLevy said the marriage was a personal affair, affecting only him and his wife and their families.

1955 – 1957

On November 8, 1955, Jasper McLevy was elected mayor of Bridgeport for a 12th consecutive term. But this time it was not the clear landslide he had experienced the previous 11 times he had been voted the city’s chief elected official. The official tally gave Democrat Samuel Tedesco 17,314 votes, Republican Max Frauwirth 9,848 votes, and incumbent Socialist McLevy 22,682 votes.

For the first time since 1933, McLevy did not earn the majority of votes cast for mayor. In fact, the combined tally of the other two candidates exceeded McLevy’s tally by 4,480 votes. This loss of popularity did not shock McLevy. He was now 77 years old, and many of his supporters were moving to the suburbs.

Nonetheless, even on the day of the 1957 election, McLevy stuck to his usual ways. Leaving his home at 463 Salem Street in Bridgeport’s north end, McLevy met with his fellow Socialist Party members at Workmen’s Circle Educational Center at 12 Hudson Street to drink tea and sit by the radio, waiting for the election results.

It soon became evident that his Democratic challenger, 40-year-old attorney Samuel Tedesco, was garnering more votes. Ironically, the last time a Democratic had done as well in the Bridgeport mayoral election was in 1931, when Democrat Edward Buckingham had narrowly defeated McLevy. Two years later, of course, McLevy would win, grabbing the job of mayor from Buckingham and holding it for the next 24 years.

Perhaps McLevy experienced political déjà vu in 1957 when Tedesco won the election, finally ousting him. The citizens of Bridgeport had again voted for change, bringing to an end the longest mayoral term in Bridgeport’s history, the longest running term of city’s only socialist mayor, and, according to the November 19, 1962 Bridgeport Sunday Herald, “one of the longest continual terms in the history of democracy.”

Jasper McLevy, the Bridgeport Herald continued, had taken “a despairing; bankrupt city [that]had called him forth as their savior from political corruption. He responded with the zeal of an avenging knight.”

Jasper McLevy died November 20, 1962.

Mary Witkowski is the archivist at the Bridgeport History Center and the current Bridgeport City historian.