by Allison Speicher WINTER 2016/17

by Allison Speicher WINTER 2016/17

From the lexical contributions of West Hartford’s Noah Webster, the “Schoolmaster of the Republic,” to the reform efforts of Hartford’s Henry Barnard, the first U.S. commissioner of education, Connecticut has long held pride of place in the history of American education. Even Ichabod Crane, the protagonist of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820) and one of America’s first fictional schoolmasters, hails from Connecticut, “a State which supplies the Union with pioneers for the mind as well as for the forest,” sending forth “legions” of “country schoolmasters.”

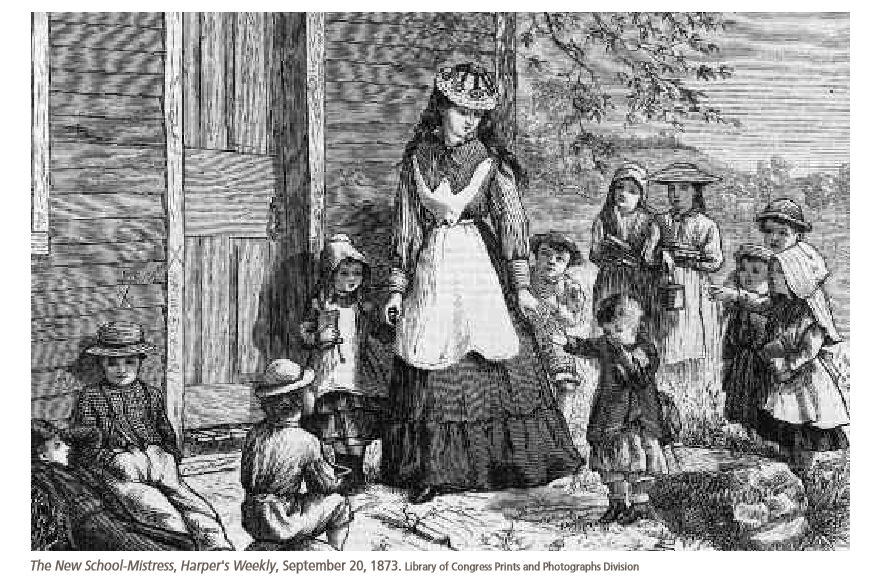

But in the 19th century, Connecticut did not just send forth schoolmasters: between 1847 and 1858, 600 schoolmistresses set forth from Hartford to teach schools in the Midwest and West. They did so under the auspices of the National Board of Popular Education, the brainchild of Catharine Beecher (1800-1878), another Connecticut resident who profoundly shaped the development of mass education. Though today her fame is dwarfed by that of her sister, author Harriet Beecher Stowe, in her own lifetime she enjoyed considerable celebrity as one of the foremost experts on education and domesticity. Author of 30 books, ranging from domestic advice manuals to textbooks to memoirs, Beecher was widely known as a pioneer educator. Through her tireless efforts, she was instrumental in opening the teaching profession to women, changing the face of public schooling in the process.

As the eldest daughter of one of America’s most famous ministers and the sister of seven others, Beecher was well poised to become an evangelist in her own right, spreading the gospel of popular education. Beecher was appalled that the important work of teaching was widely regarded as drudgery undertaken out of financial necessity, performed by men with little training or relish for the task. In her voluminous writings, she proposed a solution to this problem: make teaching a profession for women, a bold idea in an era that strongly associated middle-class womanhood with domestic avocations. In “Suggestions Respecting Improvements in Education” (1829), Beecher explains that allowing women to teach will open to them “the road to honourable independence and extensive usefulness” without forcing them to “outstep the proscribed boundaries of feminine modesty.” In “The Duty of American Women to their Country” (1845), Beecher proclaims that woman is “the best, as well as the cheapest, guardian and teacher of childhood” because she “has tender sympathies which can most readily feel for the wants and sufferings of the young.” Not only would children benefit from the loving lessons of female teachers, but women as a sex would be “elevated” by access to a respectable means of earning income.

In short, teaching would allow women to be both professional and womanly, to contribute meaningfully to society and their own support without encroaching on male territory. For women to succeed as teachers, they needed access to more substantial education, like that Beecher herself offered through the schools she founded, Hartford Female Seminary (1823), Western Female Institute (1833), and Milwaukee Female College (1850). Much as men were trained for their work as doctors, ministers, and lawyers, Beecher believed that women needed to be trained for the profession of teaching.

The feminization of teaching would not just change the lives of women and children. In Beecher’s eyes, the fate of the nation itself was at stake. In “The Duty of American Women to their Country,” Beecher sounds an apocalyptic note: “This is the way, and the only way, in which our nation can be saved from impending perils. […T]hough the peril is immense, and the work to be done enormous, yet it is in the power of American women to save their country.”

Why did Beecher think America needed saving? She, like many others, was deeply fearful of the changes occurring at mid-century, especially increasing immigration, the rising number of American Catholics, and the settlement of the West. As Jeanne Boydston, Mary Kelley, and Anne Margolis explain in The Limits of Sisterhood (University of North Carolina Press, 1988), “Beecher did not recognize, in racial, class, religious, or ethnic backgrounds other than her own, the stuff of which American civilization could be made.” She sought instead to remake the Midwest and West in her own image, to turn what she saw as an educational and moral wasteland into a place far more like her idealized vision of New England.

To do so, she suggested sending New England teachers to the West, where she estimated one million adults were illiterate and two million children did not have access to schooling. Her plan aimed for nothing short of the moral regeneration of the nation. One contemporary supporter equated each new schoolhouse to “a city set upon a hill,” likening the mission of New England teachers in the West to that of New England’s Puritan founders.

Fired by her holy cause, in 1846 Beecher put her plans into action, organizing what would become the National Board of Popular Education. She launched an extensive publicity tour, developing moral and financial support for her plan and gathering endorsements from America’s leading educators, including Horace Mann and Henry Barnard. As Kathryn Kish Sklar explains in Catharine Beecher: A Study in American Domesticity (Yale University Press, 1973), Beecher was tireless in her efforts: within five weeks, she spoke in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, New York City, Troy, Albany, and Hartford, garnering extensive news coverage in the process. She sent articles to newspapers and to clergymen, soliciting donations and the names of prospective teachers. Beecher’s efforts were highly successful: by the summer, she raised enough money to hire a full-time agent to locate positions for teachers, raise funds, and coordinate local support. Beecher chose William Slade, former governor of Vermont, for the job, and spent the fall working with him before he departed for his post in Ohio and she turned to training the first group of teachers.

Who were these intrepid educators, and why did they offer themselves up to Beecher’s cause? Thanks to a large collection of their letters, housed at the Connecticut Historical Society, we have a strong sense of their motives and characteristics. As Polly Welts Kaufman explains in Women Teachers on the Frontier (Yale University Press, 1985), more than two-thirds of the teachers were already self-supporting, having taught three years or more. Most importantly, these women shared Beecher’s evangelical vision. As part of her application, each volunteer included an essay containing her views on regeneration, “a holy change, in the affections of the heart, or commencement of holiness in the soul,” as one applicant put it. Many also included testimonials from ministers or educators attesting to their education, teaching ability, and moral character. As Slade explained, “Competent knowledge, good sense, sound discretion, decided piety, a strong desire to do good, a cheerful, hopeful spirit, and patient energy, are qualifications indispensable for the service to which the teachers are invited.”

The teachers’ letters of application highlight precisely these qualities. The women routinely invoke their desire to be “instruments of doing good” and their willingness to endure privations to do so. Looking to devote their lives to Christ, many felt, as Mary Allen did, that they might “be the means of doing more good, in the destitute, valley of the West, than in Conn[ecticut].”

Many volunteers also shared Beecher’s fears about the future of the West and the nation. Like Beecher, Mary S. Arnold, for example, expressed concern about immigration: “[W]hile the countries of the old world are emptying their overflowing population upon our shores, and Error with its subtle garb is insinuating itself into the midst of our own people,” even the weakest soul cannot afford to “withhold her mite of influence from the cause” of advancing “the Redeemer’s kingdom.”

Many volunteers also shared Beecher’s fears about the future of the West and the nation. Like Beecher, Mary S. Arnold, for example, expressed concern about immigration: “[W]hile the countries of the old world are emptying their overflowing population upon our shores, and Error with its subtle garb is insinuating itself into the midst of our own people,” even the weakest soul cannot afford to “withhold her mite of influence from the cause” of advancing “the Redeemer’s kingdom.”

Once applicants were accepted, they journeyed to Hartford for six weeks of teacher training, supervised at first by Beecher and later by Nancy Swift. Classes of around 30 were trained then sent West during the fall and spring of each year, starting in 1847. As Kaufman explains, during their intensive training, the candidates learned pedagogical and disciplinary techniques and brushed up their knowledge of composition, spelling, music, math, and physiology. They attended lectures and visited schools, the Wadsworth Atheneum, the state house, and the Charter Oak. Once they were trained, the women made their way to the West, sometimes as far away as Oregon, often journeying two to four weeks before arriving. The board paid for the teachers’ Hartford-based instruction and the trip west, but after that Slade “trust[ed]to their energy, prudence, and capacity as instructors to secure the confidence and support” of the communities to which they were sent. Each woman was expected to teach at least two years and to refund her expenses, estimated at $100, if possible.

Once she arrived in the West, each teacher was on her own. Some taught in large brick seminaries; some, in one-room schoolhouses; others, within homes or churches. While some received a warm welcome, others found that their arrival was unanticipated or that the community harbored antipathy toward Easterners, women teachers, or evangelicals. The letters they sent back to their instructors in Hartford reveal the difficulties they faced, their views of the West, and their understanding of the value of their work. Often, they paint Westerners as ignorant and uneducated, reinforcing Beecher’s bleak impression of the West. Writing from Cassville, Missouri, in 1850, for example, Martha M. Rogers claimed that several of her teenage students were illiterate, as were their parents. Emma P. Farrar ultimately left her school in southern Illinois in 1853 because “the people are almost entirely indifferent to the educational interests of their place.” Those who placed little importance on schooling also placed little importance on paying the teacher; financial woes are commonplace in the teachers’ letters home. Writing from Belleville, Illinois in 1853, for example, Elizabeth Hill claimed she was “obliged to deny [herself]even necessary articles of clothing.” In Iowa, Arozina Perkins similarly feared she would soon be “obliged to wear a blanket.” Many of the women also express displeasure about their boarding places and their ramshackle schoolhouses.

Despite the hardships they faced, however, the teachers’ letters are also filled with enthusiasm. In 1855, Maria Atwater, for example, referred to her adopted home, Perry, Arkansas, as a “benighted portion of the West,” pervaded by a “heathenish darkness,” that tested her “missionary spirit daily.” Even so, she continued, “My school is all I could expect and wish.” Such comments form a veritable refrain in the teachers’ letters: although they find Westerners “uncultivated” and “backward,” many also rejoice in their successes and find deep meaning in their work. As Elizabeth Bachelder, teaching in Mooresville, Indiana, explained in 1852, such ignorance was not limited to the West: “I have seen in favored New England, as backward pupils as anyone will be able to find in this County.” When she arrived in Dodgeville, Wisconsin in 1852, Sarah J. Dudley found “the prejudice against American teachers was very bitter” but she soon “gained the love of the scholars.” In many of the letters teachers joyfully remark that their students have made “considerable improvement” and that they are kind, affectionate, obedient, and eager to learn. Though some, like Mahala Drake, teaching in Camanche, Iowa, expressed intense homesickness, far more embraced life in the West. H.M. Hurton, teaching in DeWitt, Iowa, wrote in 1853, “I like the West so much, and see so much need of teaching here, that I have no intention of ever going home.” Indeed, according to Kaufman, two-thirds of National Board teachers never did, choosing to remain in the West all their lives.

Though the National Board managed to place hundreds of women in Western communities, some of which had never before had access to schooling, reactions to the board were mixed. Writing to the Christian Advocate and Journal in 1847, the year the first teachers were sent out, a Hoosier summarized Westerners’ objections. Easterners come to the West, he explained, “expecting to find a class of persons but one degree above savage life,” while in actuality they are “really inferior in talent to very many of those on whom they look with contempt and ridicule.” In short, the West was not a moral and intellectual wilderness awaiting the civilizing influence of New England, as Beecher and her supporters imagined it to be. Furthermore, the writer contended, the West was quite capable of furnishing of its own teachers. Others objected to the board’s religious leanings: while it claimed to be nonsectarian, it only accepted applications from Presbyterians, Methodists, Congregationalists, Baptists, and Episcopalians. Given this evangelical bent, many Catholics in particular were skeptical of the board and, indeed, some of the teachers’ letters openly rejoice that their schools will compete with and undermine Catholic schools.

Despite her enthusiasm for the project, Beecher herself was aware of its flaws. Though the organization of the board in 1846 was the culmination of decades of her labor, in 1848, Beecher left the organization, dissatisfied with Slade’s leadership and discontent to play a secondary role in an organization she had founded. Beecher worried that the board did not do enough to support the teachers once they arrived in the West, traveling west herself to care for “stranded teachers” both monetarily and emotionally. Beecher also criticized Slade’s sectarianism, though, as Sklar emphasizes, Beecher “believed this of Slade because she wanted to, not because it was true.” Regardless of her motives, Beecher left the organization to pursue a new plan for educating the West.

Rather than importing teachers from the East, Beecher turned her attention to training teachers in the West, founding the American Woman’s Educational Association in 1852 to, as she described it, “establish endowed professional schools” in which “woman’s profession should be honoured and taught.” As she explained in Educational Reminiscences and Suggestions (1874), such schools “would be permanent centers of influence,” “train up teachers for all the vicinity around,” and “raise the standard of female education.” Beecher acknowledged that the West was already home to many women who “would make just as good teachers” as Easterners if similarly trained; as an added benefit, they would “encounter less prejudice and suspicion” than Eastern teachers. In pursuit of this goal, Beecher founded teacher-training schools in Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, including Milwaukee Female College, which eventually became part of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

By the time of her death in 1878, much of Beecher’s vision for American education had become a reality. Teacher-training institutions proliferated, and girls accounted for more than half of high school graduates. Women outnumbered men in the teaching profession three to one nationwide. Educated single women could support themselves without depending on marriage or male relatives; teaching had indeed become a rewarding and remunerative profession for women, just as Beecher had hoped. Although Beecher’s nativism and cultural chauvinism should trouble us, acknowledging her flaws does not preclude appreciation of her lifelong commitment to improving the lives of women and children and her significant influence on American education. Through her work with the National Board, her writings, and her many other reformist endeavors, Beecher continually preached that teaching is a skilled profession and that care work is real work. These lessons are as relevant in the 21st century as they were in the 19th.

By the time of her death in 1878, much of Beecher’s vision for American education had become a reality. Teacher-training institutions proliferated, and girls accounted for more than half of high school graduates. Women outnumbered men in the teaching profession three to one nationwide. Educated single women could support themselves without depending on marriage or male relatives; teaching had indeed become a rewarding and remunerative profession for women, just as Beecher had hoped. Although Beecher’s nativism and cultural chauvinism should trouble us, acknowledging her flaws does not preclude appreciation of her lifelong commitment to improving the lives of women and children and her significant influence on American education. Through her work with the National Board, her writings, and her many other reformist endeavors, Beecher continually preached that teaching is a skilled profession and that care work is real work. These lessons are as relevant in the 21st century as they were in the 19th.

Allison Speicher is an assistant professor of English at Eastern Connecticut State University and the author of Schooling Readers: Reading Common Schools in Nineteenth-Century American Fiction (University of Alabama Press, 2016).

LISTEN: Allison Speicher at the Presidents’ College/CT Explored lecture series “Connecticut in the American West,” recorded February 2017.