by Gene Leach and Nancy O. Albert

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc SUMMER 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“Hartford, Ct. newboys and girls. Girl in middle, Nellie, is 9 years old.” March 1909. Photo: Lewis Hine. The Connecticut Historical Society Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

Child labor. Today the term instantly summons other terms: “social problem,” “exploitation,” “child abuse.” Until the early 20th century, however, the practice of sending children to work was commonplace in Connecticut. These photos belong to a period of transition and ambiguity, when child labor was still familiar but coming under criticism and beginning to decline.

“Stringing Tobacco. The 10 year old makes $.50 per day. Hazardville, Ct., 9 August 1917.” Photo: Lewis Hine. The Connecticut Historical Society Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

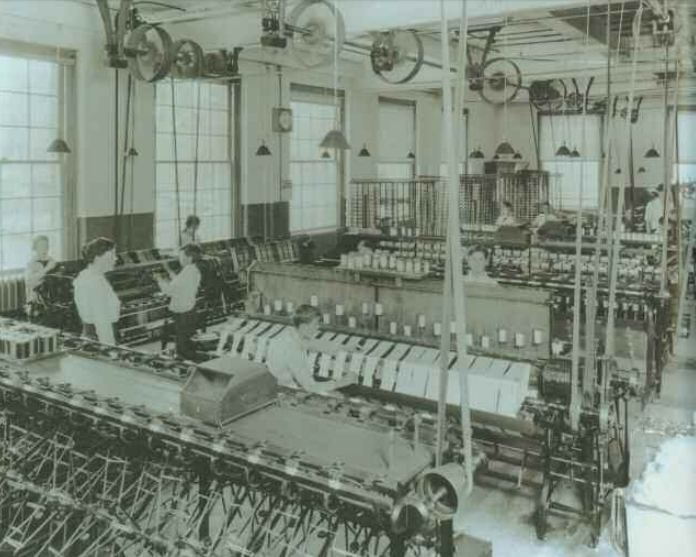

The earliest photograph (below) shows the employees of the Hop River Warp Company, a textile firm in Willimantic (1887). One-third of them are children. The faces are uniformly grim; factory work was hard on employees of all ages. But the picture reveals something else as well: a number of the child workers appear to be sons and daughters of adult employees. Child labor almost always proceeded from a family’s economic needs. The children at this Willimantic workplace labored under the oversight of parents as well as bosses.

The pictures of Hartford newsboys, newsgirls, and messengers seem to tell a lighter story (1909). Some of the youngsters grin at us, others appear composed and self-possessed. Plying their trades in city streets, these children, immigrants or the offspring of immigrants, evidently enjoyed the freedom their work gave them, even if the hours were long and the pay was poor.

Hop River Warp Co. Employees, May 24, 1887. Photographer unknown. The Connecticut Historical Society Museum, Hartford, Connecticut.

The “portrait” of the adolescent boy who gazes at us from the floor of the Cheney silk mill in Manchester (1924) was made by Lewis Hine, who worked as staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, a group pledged to do away with the employment of underaged workers. It is an image of child labor in retreat, for the NCLC titled it “Young man … working under favorable conditions….”

In the preindustrial economy of early America there were many tasks and much demand for child labor. It was thought natural for children as young as six or seven to help shoulder the burdens of household production and for youngsters in their early teens to take on gainful employment outside the family. Until the 20th century, in fact, the “child labor problem” that worried most people was the problem of children left unemployed, their laborpower wasted, their idle minds the devil’s playground.

But if it was long thought “natural” for children to work by hand in farms and shops—for example, the girls stringing tobacco in Hine’s 1917 photograph—it seemed less acceptable for children to spend long hours operating machines in factories and mines. A new concept of childhood was taking form, as a stage of life decisively different from adulthood, defined by dependency, play, and schooling. As the spheres of home and work drew apart, middleclass Americans decided children belonged at home with their mothers or at school under the supervision of female teachers. Children of the working class, however, continued to cross the boundaries between home and work, adulthood and childhood. Regional differences

“Young man, half-length portrait, standing, working under favorable conditions, in Cheney silk mills, Manchester, Connecticut.” 1924

coincided with class differences. In 1896 children made up one-quarter of the cotton mill workers in North Carolina but just 4 percent of the mill workers in Massachusetts.

Connecticut adopted the nation’s first child labor law in 1813, a paternalist act that required manufacturers to provide education and moral guidance for their child employees. An 1841 Connecticut law set 10 hours as the maximum work day for mill hands under 14 and decreed that no one under 15 could work without certification of school attendance. These early statutes were laxly enforced. By the 1880s, however, the state was putting teeth into its restrictive legislation, and throughout the North child labor was shrinking. Middle-class ideals of childhood gradually became normative for children of all classes. When national legislation barring exploitative child labor was finally adopted in the 1930s, there was little of it left in Connecticut.

Explore!

“To Work or To School: Educating Children in 19th Century Connecticut,” Summer 2009