(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Summer 2016

Subscribe to receive every issue!

Historian Bruce Daniels’s The Connecticut Town: Growth and Development 1635 – 1790 (Wesleyan University Press, 1979) is a terrific resource for understanding how Connecticut came to consist of 169 independent towns. The geographic pattern of settlement by the English (greatly simplified by necessity here) begins, perhaps not surprisingly, along the coast and major rivers. Water was an important resource and means of transportation, after all.

Geography is Destiny

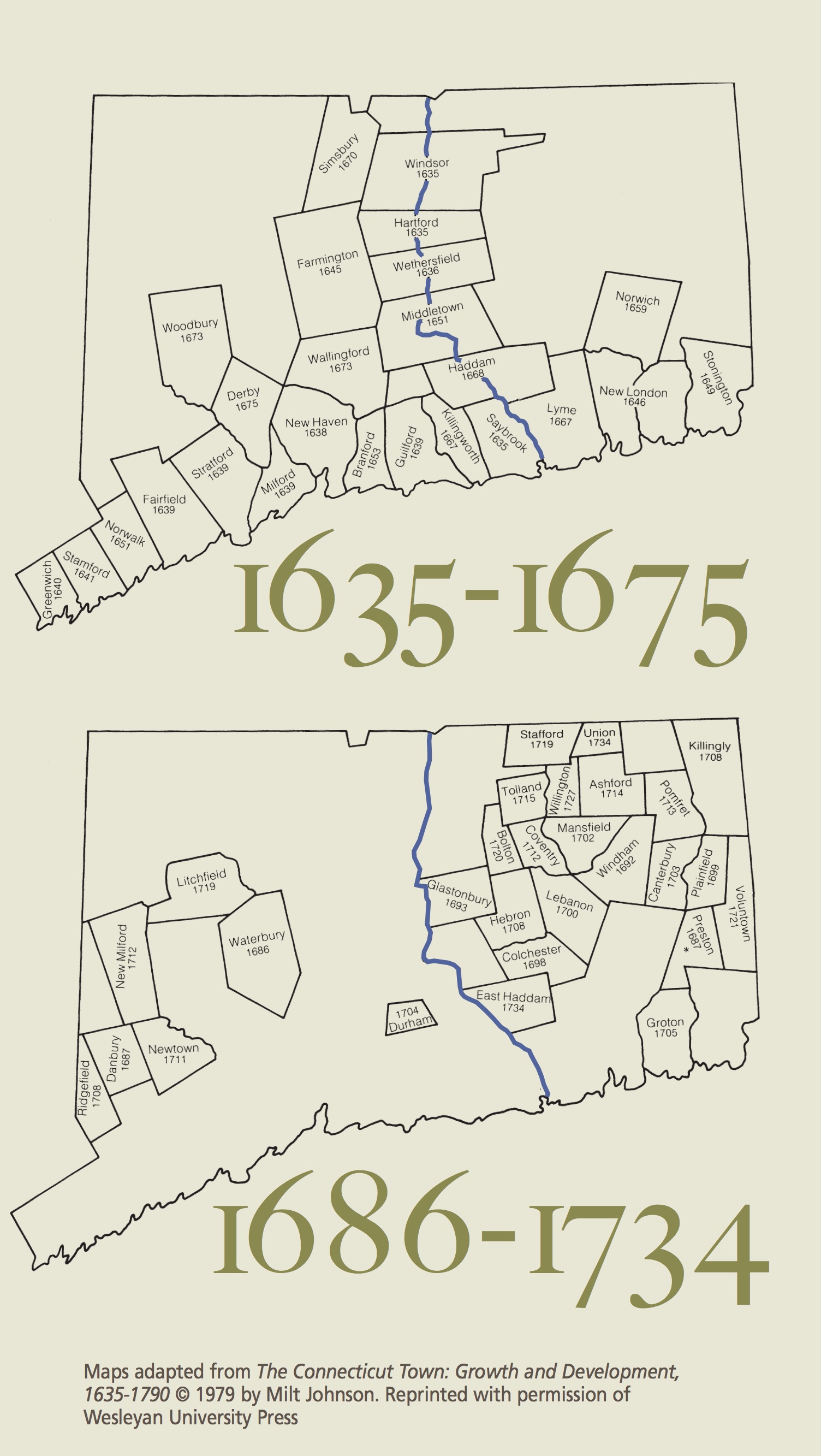

During the first period of settlement, from 1635 to 1675, 25 towns from Greenwich to Stonington on the coast and up the major river valleys were settled by family groups. “Farming, trading, and religious purity,” Daniels notes, were motivating factors in these towns’ settlement.

The Connecticut Colony formed when the earliest settlements, the inland “river towns” of Hartford, Wethersfield, and Windsor, banded together to wage war on the Pequots (a bloody conflict that took place in 1637) and other Indian peoples. [See “Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War, Fall 2013.”] The shore towns of New Haven, Milford, and Guilford created the New Haven Colony for similar purposes and to claim territory for further English settlement. Both colonies contested territorial claims by the Dutch and guarded against interference in their affairs by the English crown. In 1665 Connecticut and New Haven merged into a single Connecticut Colony under the leadership of Governor John Winthrop, Jr.

According to Daniels, during a second period of settlement (1686-1734), 29 towns formed in less fertile uplands along rivers too small for large watercraft but big enough to power mills. Twenty-four of these were new, and 5 “hived” off of existing towns. Twenty-two of them were east of the Connecticut River. “Hiving” often occurred when the population of a town grew to a point that made governance by town meeting unwieldy or when an area grew populous enough to suppor t its own church and minister. Towns during this period were settled primarily by farmers, but land speculators played a part, too. Economic drivers predominated. No Connecticut town was founded solely for religious ends, Daniels observes.

t its own church and minister. Towns during this period were settled primarily by farmers, but land speculators played a part, too. Economic drivers predominated. No Connecticut town was founded solely for religious ends, Daniels observes.

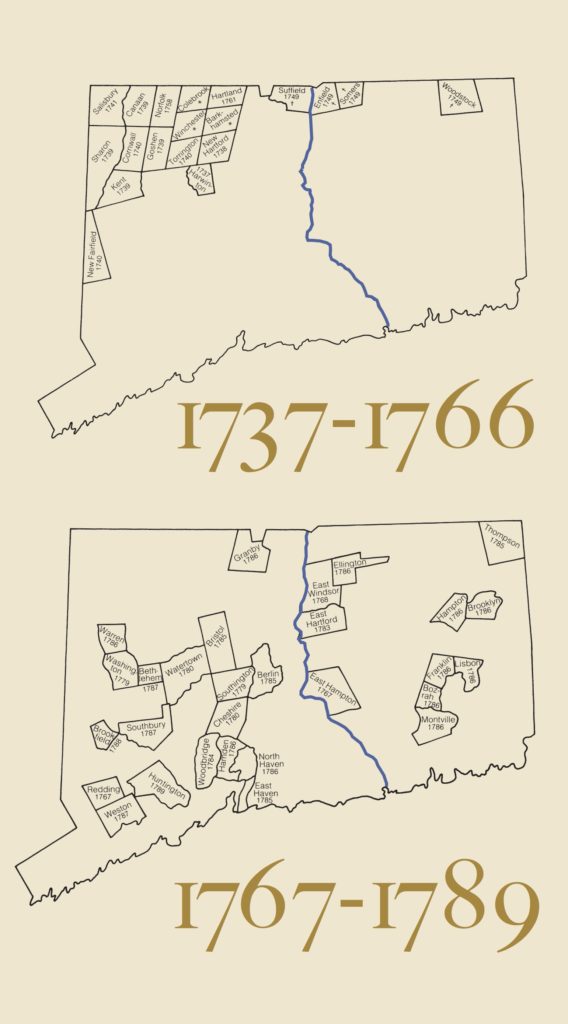

During the third period of settlement, between 1737 and 1766, 14 towns formed in the only remaining unsettled lands: those in Litchfield County. In addition, four Massachusetts towns were annexed by Connecticut. The towns in Litchfield County were distinct in that they were formed by companies of proprietors who planned the new towns with a business-like precision—and then offered the lots to settlers or groups of settlers. By the end of the colonial period the area we know as Connecticut had taken its final shape (except for minor boundary changes) and there were settlers in every corner.

The fourth and final period of town formation, extending through the 19th century and into the 20th, gave rise to 29 new towns split off from the territory of previously established ones. The last of these was West Haven, incorporated in 1921. Of the towns formed in the first period, Stonington has the distinction of being the only one that remained intact through 1789 when Connecticut became a state.

169 Independent Towns?

Today we think of Connecticut ‘s 169 independent towns and its near lack of county government together as a signature characteristic of the state. But readers might be surprised to know that this belies our early history. Colonial Connecticut was actually characterized by tight and uniform control of towns by the colony’s general court (renamed the general assembly in 1698). Not only did the general court authorize the creation of towns, it required them to conform to a governing structure and laws that they prescribed. This is in contrast to Rhode Island, where, Daniels asserts, “towns were practically self-governing republics in the 17th century; at one time, individual towns could actually nullify a statute of the General Court.” With regard to the relative powers of central and local governments, Massachusetts fell somewhere between Rhode Island and Connecticut.

Congregational churches also played a considerable role in the governance of early Connecticut towns. There was no separation of church and state as there is today. In fact, under English law that remained in force until the revolution, a town couldn’t exist without a church. Congregationalism was the established church of Connecticut through the whole colonial period and then retained this privileged status after Connecticut became a state. Until 1818, when congregationalism was finally disestablished, a portion of public taxes supported ministers’ salaries, local church expenses, and the common schools that churches in each town had the primary responsibility to provide.

As described by Glenn Weaver in Hartford: An Illustrated History of Connecticut’s Capital (Windsor Publications, 1982), each town’s church society was autonomous in its operation from both other churches and the general court. In Hartford, both men and women were admitted to membership after a conversion experience though women were not allowed to hold office or speak at meetings. Apprentices and enslaved people were admitted to membership “provided the master would serve as a spiritual overseer,” Weaver notes. Members were required to attend two services on Sunday and one on Thursday or pay a fine. Congregationalists rejected all holy days and ignored Christmas and Easter. [See “Christmas in Connecticut,” Winter 2010/2011.]

As described by Glenn Weaver in Hartford: An Illustrated History of Connecticut’s Capital (Windsor Publications, 1982), each town’s church society was autonomous in its operation from both other churches and the general court. In Hartford, both men and women were admitted to membership after a conversion experience though women were not allowed to hold office or speak at meetings. Apprentices and enslaved people were admitted to membership “provided the master would serve as a spiritual overseer,” Weaver notes. Members were required to attend two services on Sunday and one on Thursday or pay a fine. Congregationalists rejected all holy days and ignored Christmas and Easter. [See “Christmas in Connecticut,” Winter 2010/2011.]

By the turn of the 18th century, though, the Puritans were losing their iron grip—both through internal doctrinal conflict and through the increase in the number of people in Connecticut who were considered “dissenters.” Three years after the first Baptist parish formed in Groton and a year after the first Anglican parish formed in Stratford, the general court begrudgingly, according to Daniels, passed the Toleration Act of 1708. The act gave “dissenters” the right to worship but not the rights to become a religious society. Their members’ tax dollars still supported the congregational church until an act passed in 1727 allowed Anglicans, Quakers, and Baptists (but no others) to direct their taxes to their own churches. Those churches were not given the full rights of ecclesiastical societies until 1784 (1843 for Jewish congregations). Inhabitants who did not declare membership in a church had their taxes automatically given to the congregational church.

All Hands

But even in a colony as compact as Connecticut, distances were too great to allow the general assembly to exert its authority constantly or directly. In practice most day-by-day governance happened at the town level and required a great deal of local participation. With no paid town or state employees, keeping order and providing essential services fell to townsmen elected to positions with such colorful titles as fence and chimney viewer, hayward, ratesman, packer, and sealer. But not everybody could run for local office or vote.

There was a kind of class system in early Connecticut that stands in stark contrast to the ideals of equality and inclusion that later took hold in the American imagination. In early Connecticut towns—where there was little ethnic or racial diversity—there were three levels of recognized inhabitants, plus an invisible group. The most select level was the proprietors—the original settlers of the town. They (not the town) controlled the division of and management of land—much of which was held in common. New Haven initially required proprietors to be members of the congregational church, though that rule was not widespread in other towns.

There was also a class called freemen who, once admitted by the general court (before 1729) or the town selectmen (thereafter), had voting rights that entitled them to vote for town and colony-wide offices, including the town’s representatives to the general court and the governor. There was an age and property requirement to qualify, and sometimes a term of residency in town. The property requirement decreased as time went on, and the trend was to expand white male suffrage.

The third class of people was called simply “inhabitants.” Inhabitants could participate in town-level elections. But because by colonial (and later state) law towns were responsible for caring for the poor and indigent people within their boundaries, they were careful about who they allowed to be inhabitants. Daniels notes, “Without written affidavits from outside authorities or oral testimonials from local residents, a stranger would be ‘warned off’ and not allowed to settle [in town].” There is some evidence that African Americans voted in town elections and may have held local offices in a few places—historian Bruce Clouette mentions a case in Farmington in the 1600s (“Conversations at Noon,” Connecticut’s Old State house, October 13, 2015)—but it’s fair to say that an invisible class of women, free and enslaved African Americans, who accounted for just 6 percent of the population, and Native Americans were largely shut out of the political process.

The idea of universal suffrage—that every adult citizen has the right to vote—is a 20th-century notion. In the colonial era it was understood that responsibility for governance was best left to those with a vested interest in the colony—which generally meant property owners. In 1818 a letter writer to the Connecticut Courant using the nom de plume “Sydney” wrote, “Our prudent and discerning ancestors, it seems did not consider the extension of this privilege to all classes and descriptions of men as being consistent with the genuine principles of liberty, or the stability and safety of the government.” The leadership of the town therefore often fell to the same select group of men who in some cases held office for decades. “It was a deferential democracy,” notes Clouette in his Old State House talk, “in that these elections were rarely contested. There was an expectation in the 18th century, even into the early 19th century, that the most respected people would be elected over and over. That’s why the same people served for thirty, forty, fifty years.”

Towns were governed by town meeting. Eligible voters gathered twice a year or as needed to act on town business, primarily to elect town officers. Those officers included selectmen, one of whom would serve as moderator and another as treasurer. (The form and format varied over time.) The constable was the first town office created by the general court. He served as the local arm of the general court. In addition to keeping the peace, the constable supervised elections, and was entrusted to be sure all residents knew of new laws passed by the general court.

The town clerk was charged with maintaining town records. Among the lesser elected town offices were surveyors of highways (responsible for maintaining roads) and the fence viewers (responsible for maintaining fences along common lands and for corralling and returning stray livestock). A town might elect four to six fence viewers. Other positions included packers to inspect barrels of pork and beef to certify that they conformed to colony standards. Sealers did the same for tanned leather hides; there was a sealer of weights and measures who certified that scales used in business transactions were accurate. Finally, the ratesman recorded and assessed all the goods of any male older than 16 based on a schedule revised every few years by the general court.

Another obligation of male inhabitants between the ages of 16 and 60 was to bear arms and serve in the local militia. The militia became its own quasi-self-governing organization, according to Daniels. It was used in defense of the town—its creation was prompted by the declaration of war against the Pequots—but not to quell disturbances in town. In fact, Daniels notes, “the militia was more likely to cause a local disturbance than to police one; training days [held in spring and fall]were often riotous with drinking, brawling, horse racing, and shooting contests after the actual military exercises were over,” much to the chagrin of the local minister.

The Dominance of the Connecticut Town

Towns went through rapid change in the colonial period as populations grew and diversified, the congregational church lost hegemony, the economy developed and also diversified, and land had all been parceled out. Multiple factors resulted in increasing differentiation between towns over time.

In an effort to address long distances and slow communications when conducting state business, county government was established by the general court in May 1666. Four counties were established: Fairfield, Hartford, New Haven, and New London. Windham, Litchfield, Middlesex, and Tolland counties completed the system by 1785. The county governments operated jails and courts (those for probate and those handling minor civil and criminal cases) and dealt with highway and boundary disputes between towns. County government continued in these and other specialized tasks but never developed a more robust role as it did in other states. In fact, county government diminished over time and was abolished in 1960. In its place, in addition to much discussion and some action around sharing services between towns, Connecticut more recently created Regional Councils of Government. The nine RCOGs (consolidated from 15 in 2014) address the common interests of their member towns such as transit, education, land use and conservation, and economic development.

One factor in the continued dominance of the Connecticut town well into the 20th century was the way state legislators were apportioned in the general assembly. Both the senate and the house of representatives “had districts of widely varying population but the same number of representatives,” notes Wesley Horton in “The Land of Steady Constitutional Habits,” (Fall 2012). This was a situation that, Larry DeNardis reported in “Reflections on the Constitutional Convention of 1965” (Summer 2014), Connecticut was long used to: a “state house of representatives controlled by Republicans from small towns” and a state senate controlled by Democrats from the cities. The upshot was that “senate districts with 31 percent of the state’s population controlled the majority of that body… [while]the state house of representatives, based on ‘town’ representation, could elect a majority with only 12 percent of the people—the most egregious malapportionment in the nation.” It took a federal court order and Butterworth v. Dempsey (1964), brought by the League of Women Voters, to finally put one-person-one-vote ahead of the Connecticut town.

Having so many towns allows for lots of local pride and enables communities to adhere to local values and identities—all of which can foster a sense of community much valued in 21st-century America. Most towns still practice a selectmen-town meeting form of government that—as in the colonial era—requires a tremendous number of volunteer hours. Towns may no longer need fenceviewers and sealers, but they need people to serve on boards and commissions. Some fear that this system of governance is increasingly out of step with the demands of 21st- century jobs, as a result of which we see widely varying capacities among towns to carry out the responsibilities of town government. Might we see the reverse of hiving: consolidation of towns? It may make sense in theory, but it’s hard to imagine a Connecticut without its 169 unique and independent towns.

Elizabeth J. Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored and the editor of African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Elizabeth J. Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored and the editor of African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

For more information about the founding of Fairfield see “Fairfield Celebrates its 375th,” Summer 2014. For more about the founding of New Haven, Milford, Guilford, and Stratford see “Milford, Guilford, and Stratford at 375,” Summer 2014.

To learn more about the history of county government see “Site Lines: Monuments to Connecticut’s Lost County Government,” Fall 2012.