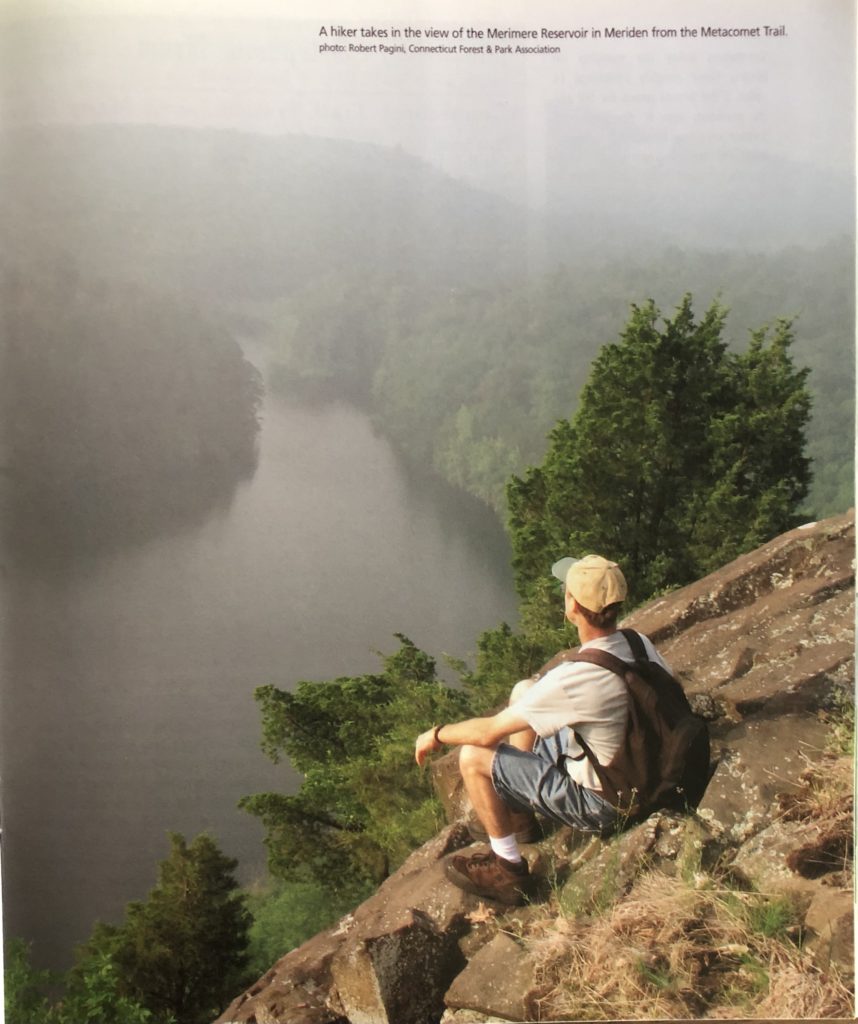

A hiker takes in the view of Merimere Reservoir in Meriden from the Metacomet Trail. photo: Robert Pagini, Connecticut Forest & Park Association

By Christine Woodside

(c) Connecticut Explored SUMMER 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

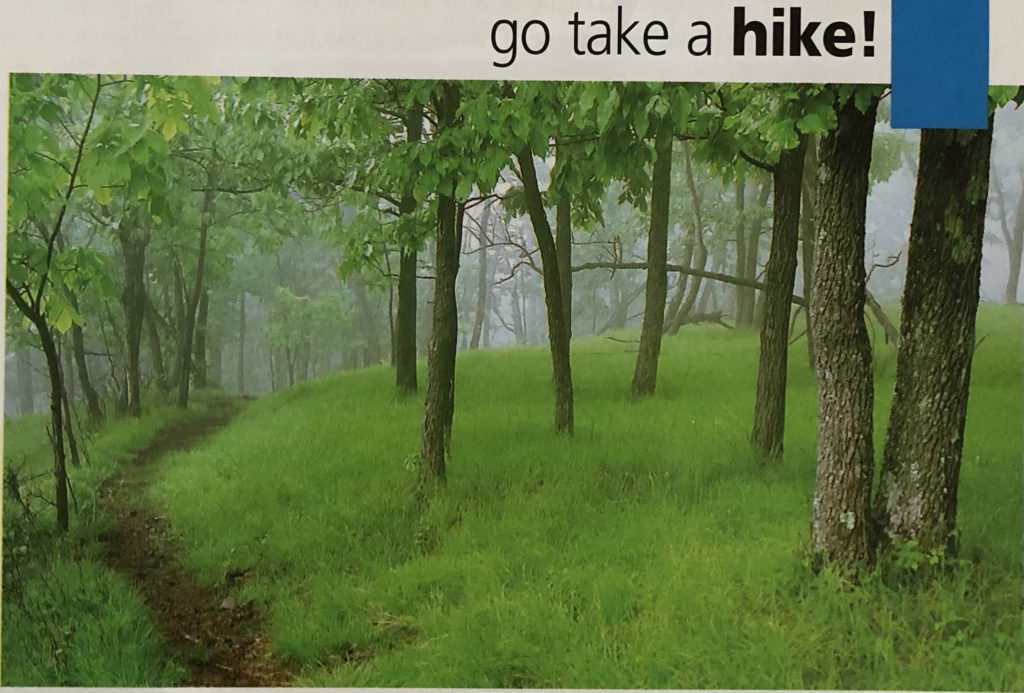

Here’s an irony: without cities and cars, Connecticut may not ever have developed its hundreds of miles of hiking trails.

Nearly a century ago, an unlikely alliance of academics and farmers in Connecticut became among the first in the nation to establish backcountry hiking trails. They were part of an East Coast movement to go “tramping” that started around 1915. Their zeal grew out of their times. In the 1910s, cities were growing and getting noisier—as they had since the Industrial Revolution began to mechanize production of goods and transportation in the 19th century. By the 1920s, automobiles were taking over the roads. As the urban world spilled out into the countryside across the Northeast, the conservation and hiking movement gathered momentum from Boston to Washington, D.C. Walking took on a new role—it became recreation, a pilgrimage to natural landscapes, a means of escaping the noise and stress of everyday urban life. As a long-time hiker, I’m hard-pressed to be grateful for noise and cars, but I am grateful for the trails they helped produce.

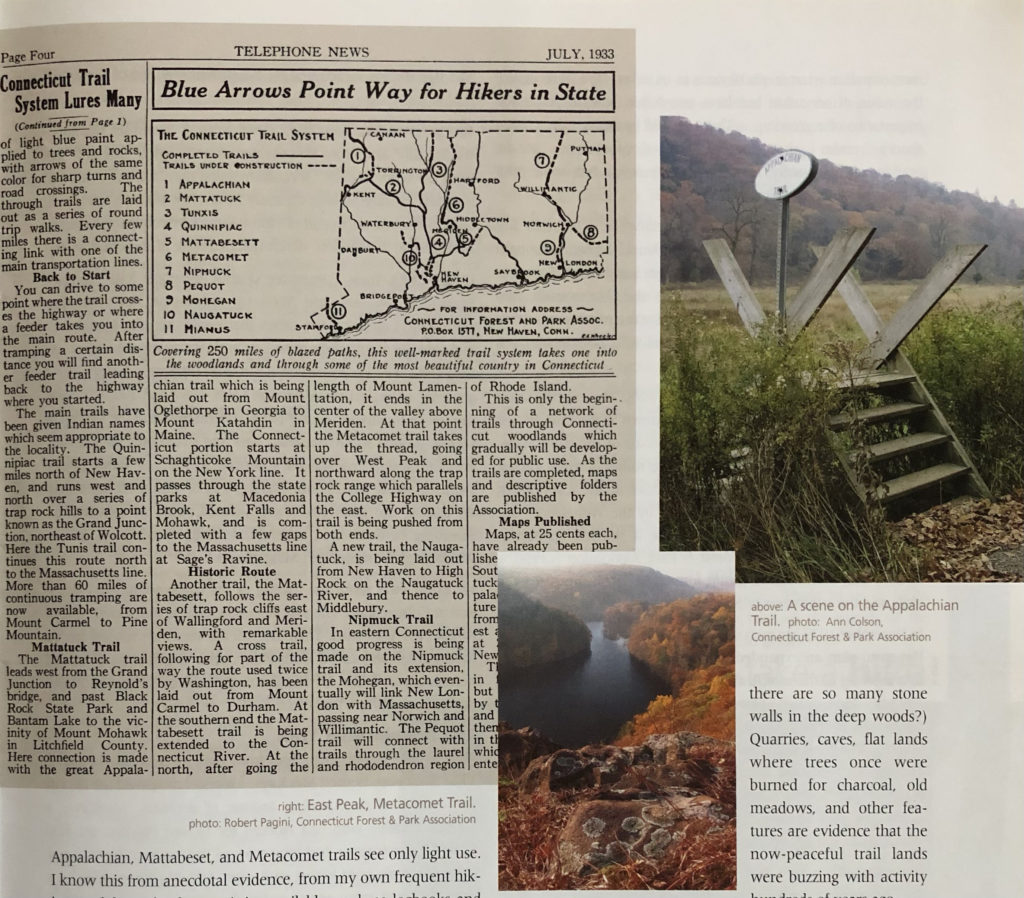

During the 1920s and 1930s in Connecticut, volunteers blazed at least 250 miles of trails, many of which still exist as part of the 800 or so miles of trails that criss-cross the state. Of all the trails established during this era, though, three are especially wonderful, and two of these are currently in the public eye. Two of the trails follow the north-south low traprock ridges in central Connecticut: the Mattabesett Trail between Guilford and Berlin and the Metacomet Trail, to which it connects, from Berlin to the Massachusetts border. The third wonderful trail is the Connecticut section of the Appalachian Trail, which runs through the state’s northwest corner, a relatively short but remarkably scenic section of arguably the most famous hiking trail in America.

The Appalachian Trail, designated as the first National Scenic Trail in America in 1968, crosses 2,175 miles from Georgia to Maine. Nearly 53 miles are in Connecticut. In that short distance, the trail goes through the Housatonic River Valley and into the foothills of the Berkshires, to the top of Bear Mountain, just south of the Massachusetts border. Connecticut is where the trail climbs out of lower elevations to higher ridges on which it then stays through much of New England. In a few days’ time, a northbound hiker passes fast-moving water surrounded by giant white pines, undulating ridges of hardwoods looking over meadow and town, and the open rocky ridge between Bear and Race mountains, with long views into rural western Massachusetts. The Appalachian Trail is all on federal land except for a short stretch that crosses the Schaticoke Indian reservation near Kent.

The Mattabesett and Metacomet trails provide tremendous views of Connecticut’s central valley as they cross mostly private tracts of land. A federal bill passed in the U.S. House of Representatives on January 29, 2008 proposes that the Mattabesett and Metacomet trails be made part of a 220-mile New England Scenic Trail from the Massachusetts-New Hampshire border south through Connecticut, and that the route be extended from the current southernmost point to Long Island Sound.

Volunteers today are working on blazing those roughly additional 14 miles. If the Senate passes the bill and the president signs it, this route will receive attention, funds, and assistance from the federal government. Such attention would draw more hikers to the trail—which is also known as the MMM Trail, after the three trails it combines, the Mattabesett, Metacomet, and Metacomet-Monadnock Trail in Massachusetts—and probably assure that it remains a trail for many years to come.

The federally protected New England Scenic Trail would differ from the Appalachian Trail in one distinctive way: the route would not become national park land, as the Appalachian Trail is. Landowners would not risk losing their land. The 30-year effort by the federal government between 1978 and today to buy or condemn land to accommodate the Appalachian Trail has left some landowners around other trails worried that they could lose their land if they allowed a trail on it. A large section of the Connecticut route of the Appalachian Trail was moved west of the Housatonic River in 1988 because landowners feared the government would take their land. That former Appalachian Trail section near Cornwall is now the blue-blazed Mohawk Trail.

Since the government began studying the possibility of a New England Scenic Trail in 2002, advocates have contended that its success will depend on the ability of hikers and trail workers to work in cooperation with landowners. They have proposed that landowners continue to own their land. That approach hearkens back to the earliest agreements for trails here in Connecticut. Until the Appalachian Trail land protection project, which created a narrow corridor of federal lands, all trails in the state were informal routes established through the good will of the property owners.

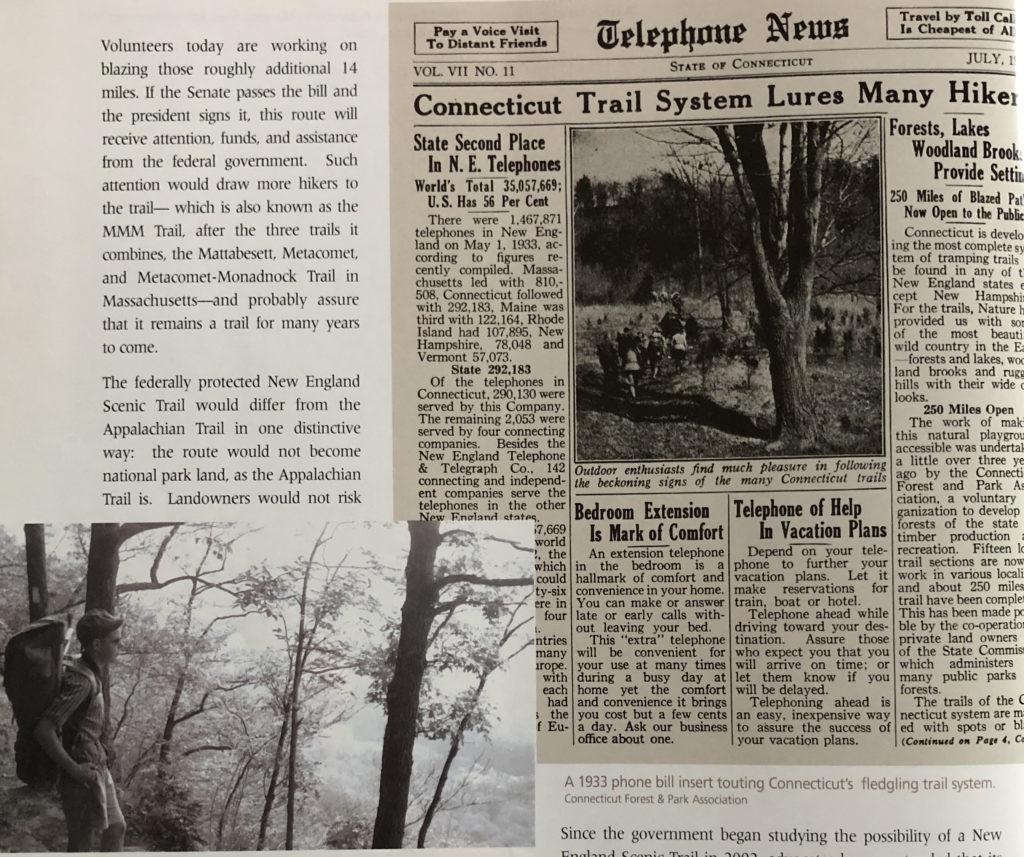

lower left: St. John’s Ledges, Appalachian Trail, 1964. Right: a 1933 phone bill insert touting Connecticut’s fledgeling trail system. Connecticut Forest & Park Association

Historic Hikes

Walk on these trails today and you might well have them all to yourself. Except for the bottleneck of a few thousand “thru-hikers” who hike the Appalachian Trail each summer, the Appalachian, Mattabesset, and Metacomet trails see only light use. I know this from anecdotal evidence, from my own frequent hiking, and from the few statistics available, such as logbooks and reports the Appalachian Trail Conservancy compiles each year. The Mattabesett and Metacomet trails, and the Appalachian Trail in the off-season, are often as quiet as the woods were last century, when these routes materialized at the hands of the volunteers.

Hiking on these trails reveals not only the beauties of a state so many of us leave when it’s time for vacation, but also the history of this land and something about the people who made the trails. Much of the woodland reforested Colonial-era farms. Stone walls from those farms meander through the forests. (Ever wonder why there are so many stone walls in the deep woods?) Quarries, caves, flat lands where trees once were burned for charcoal, old meadows, and other features are evidence that the now-peaceful trail lands were buzzing with activity hundreds of years ago.

As early as 1916, men (and it was indeed all men; whereas women helped blaze trails and further the cause of hiking in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, there’s no evidence of any woman’s participation in such activities in Connecticut during the trails’ formative years) were cutting short paths through Hubbard Park in Meriden. In 1917, Albert Milford Turner, the field secretary of the State Park Commission, observed in a memorandum what seems obvious to us today: “We all recognize the value of education but have much yet to learn about the importance of recreation…. There should be many minor open spaces under the State Park Commission, maybe one in every country town, for every town has some spot peculiarly its own.”

Frederick W. Kilbourne of Meriden, meanwhile, a librarian and the associate editor of Webster’s International Dictionary, thought of a grandiose idea for hiking: a trail from Long Island Sound to Massachusetts, what would become the Mattabesett and Metacomet trails. In 1919, he used an axe to mark a section between Reed Gap, west of Durham, and West Peak in Meriden and called it the Trap Rock Trail.

The trails movement expanded in the 1920s. The existing small and informal network of trails became known as the Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails, named for the light blue color of the paint blazes (dollar-bill-sized marks) used to mark the routes on trees. (Edgar Laing Heermance, a retired minister active in the Connecticut trails movement, chose this color, used by the Wonalancet Out Door Club in New Hampshire, because it showed up best at twilight.) The Connecticut Forest & Park Association (CFPA), a forestry and conservation group formed in 1895, organized the trails and the volunteers who cared for them.

In December 1929, six men sat down at the Graduate Club in New Haven to plan an expanded network of hiking trails. It was the first meeting of the new Trails Committee of CFPA, but they had already done much planning. They quickly adopted the philosophy of creating long routes off of which other trails would branch. The Mattabesset trail would be one of their first projects.

The Trails Committee members included Edgar Laing Heermance, a Yale Divinity School graduate, who had blazed a four-mile path near his Hamden house west of Sleeping Giant (the rock formation that resembles a sleeping man, and which today is a state park).

Extending Kilbourne’s Trap Rock Trail, by 1931, the Mattabesett Trail ran from a point 13 miles north of New Haven northward over several low traprock hills to Middletown. Named after the Indian tribe that had lived in the vicinity of Durham and Middletown, the trail was announced to the public via a CFPA “press bulletin” on November 25, 1931, assuring potential hikers that although the trail wasn’t fully cleared, it was marked with the signature paint blazes on trees. (In 1983, writing in CFPA’s magazine Connecticut Woodlands, trail volunteer Kornel Bailey wrote that he and his friends had seen that bulletin in 1931 and had gone right out to hike the new Mattabesett. “We had a hard time following the route although we were experienced hikers,” he wrote. “I have learned since that Mr. Heermance sometimes got his publicity ahead of the actual trail work.”)

The press bulletin described views from a “beautiful hemlock-shaded cliff” and, from mounts Beseck and Higby, “fine outlooks from the western cliffs.” It recommended that “for a day’s tramp, it is now possible to take the early Middletown bus to Coe’s Mill, and walk to the north end of Mount Beseck, meeting the bus from Middletown to Meriden, which makes a walk of about ten miles.”

Under CFPA Trails Committee charter members Yale Professor Everett O. Waters, and Wesleyan professor Karl Pomeroy Harrington’s direction, the crews that established the Mattabesett included the outing clubs from Yale and Wesleyan universities. As Guy and Laura Waterman wrote in their mountain history, Forest and Crag, (Appalachian Mountain Club, 1989 and 2003) “During the rest of the decade of the 1930s, Harrington and the Wesleyan youths pushed the Mattabesett east and eventually circled back north until they reached the Connecticut River at White Rocks. Thus was made a continuous hiking trail of almost 50 miles right up against the most densely populated heart of Connecticut, threading between and around the cities of Meriden, Berlin, Wallingford, Durham, and Middletown.”

We know little about the blazing of the Metacomet, my favorite trail in Connecticut. The southernmost several miles were part of Kilbourne’s Trap Rock Trail. The Metacomet was named for an Indian chief, also called King Philip, who (legend has it) staked himself out on Talcott Mountain to watch the burning of Simsbury during King Philip’s War of 1676-77.

Left: a 1933 phone bill insert touting Connecticut’s fledgling trail system. bottom: East Peak, Metacomet Trail, photo: Robert Pagini. Right: Along the Appalachian Trail, photo: Ann Colson. Connecticut Forest & Park Association

The Appalachian Trail

Plans for the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine began in 1922. That year, Benton MacKaye, a forester, proposed the idea in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. MacKaye, a Stamford native who had worked for Gifford Pinchot, the first United States forester, had long enjoyed the outdoors but was not known as a die-hard hiking enthusiast. Still, MacKaye’s idea for a very long trail came across as his deep passion, and it struck a chord. People in high places started to take it seriously. MacKaye envisioned a trail linking a series of camps relatively close to populated areas of the East that would enable people to spend more time in the outdoors. Trail conferences in Washington began to organize trail clubs up and down the Eastern Seaboard to establish sections of the Appalachian Trail, named for the lengthy chain of mountains.

In 1929, after much discussion of whether and where the route should go in Connecticut, the work to establish the Connecticut section of the Appalachian Trail got underway. Judge Arthur Perkins of Hartford was instrumental in recruiting volunteers. Perkins, who also sat on the CFPA Trails Committee, was inspired by experiences in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Perkins wrote in the June 1929 issue of Appalachia Journal (published by the Appalachian Mountain Club) that the Appalachian Trail was meant to make mountains accessible for hiking and camping and that it also would “conserve the primeval environment as a natural resource,” echoing the rhetoric of MacKaye’s original article. In Connecticut, he enlisted the help of a Sherman farmer named Nestell (Ned) Kipp Anderson, whom Perkins had met one day hiking in the woods. Anderson was busy clearing the route by late 1929, and he also established the most popular hiking trail in the state, the Undermountain Trail in Salisbury, off Route 41.

“Sacred to the Men on Foot”

Since the heady days of the trails’ development, all have been rerouted multiple times to comply with landowners’ requests—the most notable change being the relocation of the Appalachian Trail. In addition, sections of some Blue-Blazed Trails have had to close as development encroached. Overall, however, the trails as dreamed of and conceived in the 1920s have managed to survive. In the age of urban sprawl and expanding highways, that’s quite something.

The trails owe their existence to the people who care about trails. (Though men still far outnumber women on Connecticut’s trail maintenance and blazing committees, female enthusiasts are beginning to make a mark. Still, just five of the more than a hundred trail maintainers for the CFPA—including myself—are women.) Crucial to the CFPA Trails Committee’s approach was a philosophical, almost moral, connection to the backcountry. They viewed hiking as a moral act because it allowed the masses to connect with nature near where they lived, encouraging all people to value natural landscapes and not to see them as wastelands.

All trail blazers, from 1916 to today, share enthusiasm for the outdoors. There is nowhere else they’d rather be than in the woods. In January 1930, at CFPA’s annual meeting, held just a few weeks after the CFPA Trails Committee pioneers first met, keynote speaker Raymond Torrey, secretary of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society underscored the need for scenic hiking trails, noting ”The automobile bids fair to reduce legs to more or less decorative appendages, but a few still walk for their soul’s good and to the body’s profit. To do so successfully they must be protected from automobiles, trolley cars and other 20th century inventions. All over the country, hiking clubs are springing up and reverting to the ways of our ancestors by building and traversing trails, blazed or otherwise marked in approved fashions, through what is left of our wilderness. We have a few trails sacred to the men on foot in Connecticut. The need and demand for more is growing.”

The trail movement is still strong today as hundreds of volunteers continue to mark and stabilize Connecticut’s trails. Since 1979, the Appalachian Mountain Club has been the official maintaining club of the Appalachian Trail and its side trails, working through the Appalachian Trail Conservancy that handles all of the volunteer clubs along the route. CFPA oversees volunteer networks to maintain the Metacomet, Mattabesett, and all of the Blue-Blazed Hiking Trails. CFPA maintains strong ties with the property owners who allow trails to cross their land. The challenge CFPA, AMC, and other groups face today is to interest people, especially the younger generation, in the outdoors. Will the next generation unplug from the increasingly electronic world long enough to rediscover our natural world? As hikers know, a trail places you in the middle of the backcountry, both introducing you to the wonders of nature and taking the mystery out of it, and, in the process, making you care. Those of us at CFPA hope that the next generation will take up the mantle of the early trailblazers. But first we’ve got to get them to go take a hike!

Christine Woodside is the editor of two trail magazines, Appalachia Journal, published by the Appalachian Mountain Club, and Connecticut Woodlands, published by the Connecticut Forest & Park Association.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s historic landscape and environment on our TOPICS page.