By Alana Joli Abbott

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

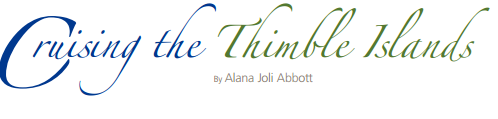

On a ferryride around the Thimble Islands, just off the shore of Stony Creek, Connecticut, you’re likely to hear from an enthusiastic captain-cum-tour guide that there are 365 islands in the chain— theoretically one could visit one a day for a year! It’s a romantic notion and a nice number, but proving it would be difficult—even counting each small rock visible at low tide. But traditional stories such as this and others that purport Captain Kidd made High Island his harbor while running from pirate hunters help give the islands their character.

On a ferryride around the Thimble Islands, just off the shore of Stony Creek, Connecticut, you’re likely to hear from an enthusiastic captain-cum-tour guide that there are 365 islands in the chain— theoretically one could visit one a day for a year! It’s a romantic notion and a nice number, but proving it would be difficult—even counting each small rock visible at low tide. But traditional stories such as this and others that purport Captain Kidd made High Island his harbor while running from pirate hunters help give the islands their character.

Labeled “The Hundred Islands” on maps made between 1715 and 1720, the Thimbles first appear under that more colorful name in Branford town records in 1739. Though the origin of the name is uncertain, historian Archibald Hanna wrote in his A Brief History of the Thimble Islands (Branford Historical Society, 1970) that the islands were named for their native thimbleberry, more commonly called black raspberry, once abundant on the islands. Today, 32 of the islands are inhabited, and for years the Thimble Island ferries and their captains have served as tour guides and keepers of the legends from the Connecticut shore to this picturesque island chain.

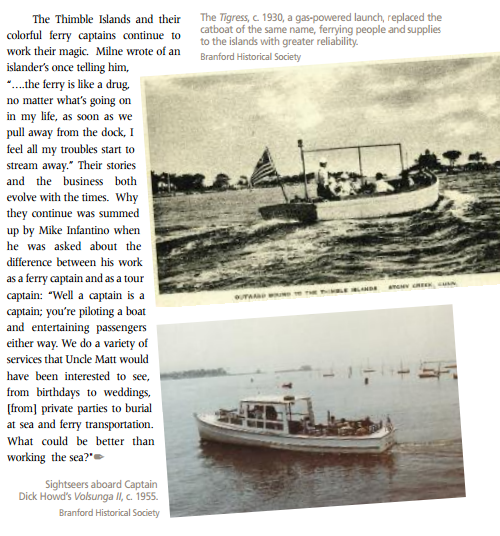

Though the early history of the Thimble Island ferries is not well documented, today’s ferry- and sightseeing-boat captains claim that ferry service between Stony Creek and the islands started as early as the mid- 1700s. But a wise traveler to the Thimbleslearnsto listen to the captains’ stories with a splash of salt water. Though they are oral historians, they are also storytellers, and, as fishermen are rumored to do, they are known to stretch the truth. As Captain Dick Howd, who captained the Volsunga from 1950 to 1973, wrote in his autobiography Welcome Aboard (K&G Graphics, 1989), “I have been known to stretch the truth now and then, but in the eyes of Neptune, King of the Seas, this is not a mortal sin for an avid fisherman.”

Tourism Take Root on Rocky Shores

In the early 1700s the islands were considered to have little economic value. They were too small and rocky for farming, though they were good spots for fishing, oystering, or gathering seaweed for fertilizer. By 1773 all of the islands had been parceled out to private families, descendants of the original proprietors of the Branford settlement.

the Branford settlement. In the 1840s a new use for the islands took hold. In July 1846 William Bryan, the enterprising owner of Pot Island, built the Thimble Island House hotel, creating a tourism industry based on the romantic notion that Captain Kidd had buried treasure on the islands. The story of Kidd’s visit to the Thimbles was established in local folklore by 1800, based on anecdotal accounts and fueled by the hopes of treasure hunters. Drawing on that legend, Bryan placed an advertisement in the New Haven Register, not for a hotel stay on Pot Island, but for a vacation on “Kidd’s Island.”

By August Pot Island became a destination for more than overnight guests. The steamer Hero, captained by R. Peck, began offering daytrips to the island. His ads in the New Haven Register and the Palladium recommended the voyage as “a fine opportunity for those fond of fishing and for invalids to enjoy the fresh sea air.” The summer was successful enough that in 1847 Bryan built two bowling alleys in the house and advertised the site’s bathing, boating, and fishing facilities. He also advertised a ferry service via sailboat from Branford Point House, a hotel run by another member of the Bryan family.

When the New Haven-New London rail line was completed in 1852, Stony Creek and the Thimble Islands solidified their reputation as a resort area, attracting families, city-dwellers hoping to escape the hustle and bustle of New Haven, and all-male fishing-parties. The ferry made regular stops at the wharf near the Stony Creek railroad stop, carrying passengers it picked up there to the Thimble Island House and other islands. Several steam ships, including Captain Peck’s Champion and Captain John Bowns’s Traveller, soon began making regular trips from New Haven directly to the Thimbles. According to Hanna, in the summer of 1855,

the Traveller … sailed every Thursday for the Thimble Islands at 2:00 p.m., returning at dusk. The Old Gents Band provided music and the fare was only fifty cents. It was little wonder that these excursions drew as many as three hundred passengers on a single day.

Annual events such as Bryan’s clambake on Pot Island drew large crowds, as did retreats hosted by groups like the YMCA, the Methodist Sunday School, and the Odd Fellows, a fraternal service organization.

Though business was slowed by the Civil War, during which steamship service was suspended, at the end of the war the Thimbles regained their status as a must-visit resort. Hotels and summer cottages sprang up on Money Island, and the steamer Alice E. Preston made two trips a day back and forth between Branford beaches and the Thimbles. When the Thimble Island House’s new owner Billy Barnes began offering a daily clambake in the summer of 1865, Ella, a barge with a 2,000-passenger capacity, was added to the daily schedule. The flurry of activity lasted only one summer, though, and the Thimbles experienced a lull in tourism until the late 1870s. During the 1880s “twenty foot gaff-rigged cat boats” made the run from Branford’s Indian Point to Pot Island, according to Bob Milne’s Thimble Islands Storybook (self-published, 2005). Families began building private summer homes on the islands, leading up to the Golden Age of tourism on the Thimbles.

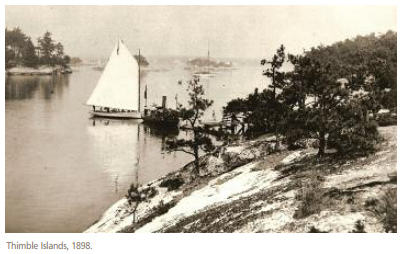

From 1890 through America’s entrance into World War I, the harbors of the Thimbles were flooded with yachts as sailing clubs made the islands one of their preferred places to drop anchor. Hanna recorded an August day in 1910 when 50 yachts from clubs in New York City and New Haven were docked among the islands. “They liked to anchor there because the islands were picturesque, and the air was fresh and the water clean,” James S. Pitkin wrote in The Rudder in 1930. He recalled Leo Spitzer of Money Island, who ran a “Rudder Station” from which he ferried supplies to visiting yachtsmen, serving as “iceman, mailman, milkman, ferryman, groceryman, etc., etc. ad infinitum.”

Other ships visiting the Thimbles included battleships from the U. S. Navy, the Connecticut, Ohio, and Minnesota, which practiced maneuvers in Long Island Sound. When landlord William Barnes decided to close the Thimble Island House in 1895, refusing to allow visitors to stop on Pot Island, steamers full of sightseers cruised around the island instead.

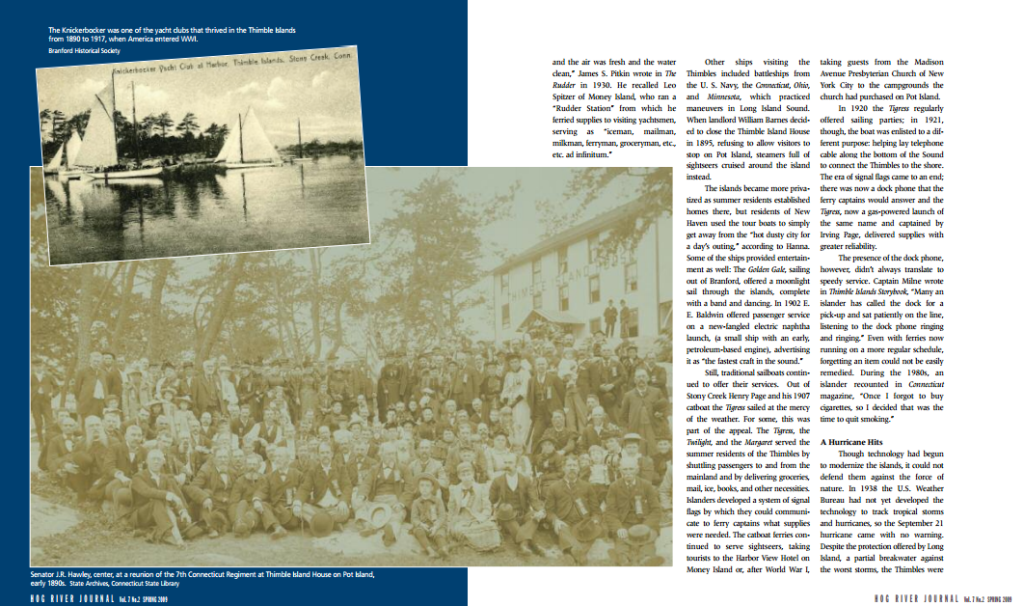

The islands became more privatized as summer residents established homes there, but residents of New Haven used the tour boats to simply get away from the “hot dusty city for a day’s outing,” according to Hanna. Some of the ships provided entertainment as well: The Golden Gale, sailing out of Branford, offered a moonlight sail through the islands, complete with a band and dancing. In 1902 E. E. Baldwin offered passenger service on a new-fangled electric naphtha launch, (a small ship with an early, petroleum-based engine), advertising it as “the fastest craft in the sound.” Still, traditional sailboats continued to offer their services. Out of Stony Creek Henry Page and his 1907 catboat the Tigress sailed at the mercy of the weather. For some, this was part of the appeal. The Tigress, the Twilight, and the Margaret served the summer residents of the Thimbles by shuttling passengers to and from the mainland and by delivering groceries, mail, ice, books, and other necessities. Islanders developed a system of signal flags by which they could communicate to ferry captains what supplies were needed. The catboat ferries continued to serve sightseers, taking tourists to the Harbor View Hotel on Money Island or, after World War I, taking guests from the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church of New York City to the campgrounds the church had purchased on Pot Island.

In 1920 the Tigress regularly offered sailing parties; in 1921, though, the boat was enlisted to a different purpose: helping lay telephone cable along the bottom of the Sound to connect the Thimbles to the shore. The era of signal flags came to an end; there was now a dock phone that the ferry captains would answer and the Tigress, now a gas-powered launch of the same name and captained by Irving Page, delivered supplies with greater reliability.

The presence of the dock phone, however, didn’t always translate to speedy service. Captain Milne wrote in Thimble Islands Storybook, “Many an islander has called the dock for a pick-up and sat patiently on the line, listening to the dock phone ringing and ringing.” Even with ferries now running on a more regular schedule, forgetting an item could not be easily remedied. During the 1980s, an islander recounted in Connecticut magazine, “Once I forgot to buy cigarettes, so I decided that was the time to quit smoking.”

A Hurricane Hits

Though technology had begun to modernize the islands, it could not defend them against the force of nature. In 1938 the U.S. Weather Bureau had not yet developed the technology to track tropical storms and hurricanes, so the September 21 hurricane came with no warning. Despite the protection offered by Long Island, a partial breakwater against the worst storms, the Thimbles were badly hit. Residents waited in their homes, all of which suffered damage, with no way to get to the safety of Stony Creek’s shore. The houses on Burr Island and Frisbie Island—one on each—were swept into the sea; a home on Jepson Island was pulled into the sea, along with all the people inside it. Seven islanders died in the storm, a number much lower than it would have been had the storm hit before Labor Day when the summer population was at its height.

But the hurricane and the economic effects of the Great Depression had inalterably changed the Thimble Islands; no longer one of New England’s major resort areas, they became a sleepier summer community for those who could still afford such luxuries. Captain Milne called this moment the end of the Golden Age, describing that while little had physically changed along the Connecticut shoreline, the coast was reshaped psychologically. “After the storm, people started thinking more modernistically, and not so idealistically,” he explained in Thimble Islands Storybook. “Many of the big inns in Stony Creek would not reopen, the trolley cars would stop running, and building right on the doorstep of the sea would be set back 10 or 12 feet to respect nature’s wrath.”

After World War II, the islanders returned to their summer homes, enjoying a lifestyle that ran on the sun’s schedule (as few homes had electricity). In his autobiography, Captain Howd wrote:

You can always tell a true islander family by the way they open up their island cottage in the spring. First, the wife arrives early in the morning with the kids, the dogs, and a week’s supply of groceries. This usually happens during the week when the husband is at work. Then the husband shows up about five o’clock on Friday with the real necessities of island living, like the fishing poles, the beer, and the evening paper.

The hotels and camps that had once lured the public to the Thimbles gave way to private residences, and Horse Island became an ecological research station run by Yale University.

Ferry Captains Tell Their Tales

The early 1950s began the era of the “ferry captain as raconteur.” Sightseers gained an added draw when Captain Dick Howd, also known as “Captain Dick from Stony Crick,” bought the Thimble Island Ferry Boat business and launched the Volsunga. For the next 23 years, residents and sightseers alike enjoyed a ride and Captain Howd’s ongoing practical jokes. An accomplished prankster and storyteller, Howd spread untrue gossip, played Polish music over his loudspeaker to wake his early-morning commuters, delivered groceries to the wrong islands, and teased regulars over the P.A. system. He gave children maps to “pirate treasures” hidden in the islands and occasionally treated them to ice cream. Surviving a prank by Captain Howd became a mark that distinguished casual visitors from accepted locals.

Matt Infantino joined in the fun, offering cruises of the Thimble Islands on the Sea Mist beginning in 1959. The Sea Mist was primarily a tour boat for sightseers rather than a combination ferry and tour boat like the Volsunga. Infantino offered a halfhour tour of the islands, accompanied by a recorded description. His nephew Mike Infantino explained in an interview for this article that his uncle ran on weekends so he could put a little extra money down on his mortgage.

In the 1970s both Howd and Infantino retired; Howd passed his megaphone to Dwight Carter (whose grandparents had died in the 1938 hurricane), while Mike Infantino, who had been a crewman under his uncle Matt, bought the Sea Mist. Both captains carried on the storytelling tradition, bringing a share of theater to their tours. Carter had been trained as an actor and developed a dramatic narrative to accompany his tour. Infantino expanded his uncle’s tour to a 45-minute trip and replaced the recorded talk with his own, interactive performance delving more deeply into the history of the Thimbles. “Matt hadn’t gone into the islands’ history so much,” Infantino told a reporter for the Shore View. “I went back and really tried to figure when things had happened.”

Captain Carter, too, focused more on the islands’ history, particularly in his recounting of the 1938 hurricane. Five of Carter’s relatives were swept off of Jepson Island during the hurricane. The island remained vacant until 1978, when Carter built a new home there, making him the seventh generation of Carters on Jepson Island.

In 1986 Carter sold the ferry service to Bob Milne. That same year Dave Kusterer, whose family had owned a house on High Island since 1903, launched a new sightseeing tour on the Islander. Despite the competition, business was good, and three years later, Milne expanded, dividing his ferry service and the sightseeing business between two vessels: the Volsunga II (later the Volsunga III and the Volsunga IV as the older boats were replaced) while the newly purchased Charly More offered the regular ferry services. In 2002, the Charly More was sold to Mike Infantino, who continues to also run his sight-seeing tour on the Sea Mist II.

The legends the ferry captains still tell are of Captain Kidd and of General Tom Thumb, who worked for P.T. Barnum, courting Little Miss Emily of Cut-in-Two Island. The story usually concludes either with Thumb’s running off with someone he met on a business trip or being forced by Barnum to marry another member of the circus. The legend of how Mother-in-Law Island got its name is about how a nosy mother invaded the privacy of her newlywed daughter and son-in-law. In retaliation, the couple took both boats and left the mother on the island by herself with no way to get home. More recent legends, including a joke started by Howd about Horse Island, “the largest island of the group, sixteen acres, fifteen of which are poison ivy,” have been quoted as fact in periodicals, giving Howd’s pranks more weight than he may have intended.

The legends the ferry captains still tell are of Captain Kidd and of General Tom Thumb, who worked for P.T. Barnum, courting Little Miss Emily of Cut-in-Two Island. The story usually concludes either with Thumb’s running off with someone he met on a business trip or being forced by Barnum to marry another member of the circus. The legend of how Mother-in-Law Island got its name is about how a nosy mother invaded the privacy of her newlywed daughter and son-in-law. In retaliation, the couple took both boats and left the mother on the island by herself with no way to get home. More recent legends, including a joke started by Howd about Horse Island, “the largest island of the group, sixteen acres, fifteen of which are poison ivy,” have been quoted as fact in periodicals, giving Howd’s pranks more weight than he may have intended.

The Thimble Islands and their colorful ferry captains continue to work their magic. Milne wrote of an islander’s once telling him, “….the ferry is like a drug, no matter what’s going on in my life, as soon as we pull away from the dock, I feel all my troubles start to stream away.” Their stories and the business both evolve with the times. Why they continue was summed up by Mike Infantino when he was asked about the difference between his work as a ferry captain and as a tour captain: “Well a captain is a captain; you’re piloting a boat and entertaining passengers either way. We do a variety of services that Uncle Matt would have been interested to see, from birthdays to weddings, [from]private parties to burial at sea and ferry transportation. What could be better than working the sea?”

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Maritime history on our TOPICS page.