By Marshall S. Berdan

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All photos courtesy of Nellie Green’s family. Special thanks to her great-grand daughter, Charlene Massey, and her great-grandson, Charles William Green Talmadge III.

East Haven’s Nellie Green (1873-1951) didn’t set out to become one of southern Connecticut’s most colorful and celebrated scofflaws. For most of her 50-year career, in fact, she was a perfectly legitimate businesswoman, carrying on the established family trade. But the Green family trade happened to be inn keeping, and for an unlucky 13 years beginning in 1920—the era of Prohibition—this dynamo of a woman found herself on the wrong side of the law. Unwilling to throw in her bar towel when the nation outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors, Nellie chose to become a bootlegger and rum runner instead. By doing so, she became a living legend and a folk hero to many in Connecticut, one of only two states (the other being Rhode Island) that never ratified the 18th Amendment.

East Haven’s Nellie Green (1873-1951) didn’t set out to become one of southern Connecticut’s most colorful and celebrated scofflaws. For most of her 50-year career, in fact, she was a perfectly legitimate businesswoman, carrying on the established family trade. But the Green family trade happened to be inn keeping, and for an unlucky 13 years beginning in 1920—the era of Prohibition—this dynamo of a woman found herself on the wrong side of the law. Unwilling to throw in her bar towel when the nation outlawed the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors, Nellie chose to become a bootlegger and rum runner instead. By doing so, she became a living legend and a folk hero to many in Connecticut, one of only two states (the other being Rhode Island) that never ratified the 18th Amendment.

That Nellie Green was colorful there can be no gainsaying: she was a powerfully built sparkplug of a woman who almost made a career on the operatic stage. As celebrated and wealthy as she became by virtue of her underground career, hers was a life full of disappointment and personal tragedy—of which she made the best that she could.

Nellie Adeline Green was born on September 30, 1873, the eldest child of Charles Green and Ellen E. Glass, a woman who was seven years Charles’s senior and disabled by poor eyesight. Charles had served as a teenage drummer boy in the Civil War, only to be struck in the forehead by a ricocheting minnie ball. The ball left a permanent indentation and, according to many who knew him, an even deeper internal scar in the irascible quirky man. Green owned some 750 acres adjacent to the Farm River in East Haven, and was a plasterer by trade. But he was much more interested in hunting and made most of his meager living selling small game, clams, and fire wood and by accommodating the occasional overnight guest in the modest wood-frame house that he had built alongside the tidal river. Nellie grew up in a catch-as-catch-can environment. That environment and the influence of her father (who preferred settling his own differences with fisticuffs and so taught his daughter how to box) made a tomboy out of her. As soon as she was old enough, Nellie began contributing to the family coffers by tending the nearby drawbridge that crossed the Farm River into Branford and delivering lunches to the laborers upstream at Johnson’s Quarry.

Nellie was no stranger to strong language and didn’t suffer fools. Among the most oft-repeated stories about her tells how one day while riding through the streets of New Haven she was the object of a pedestrian’s lecherous remark. Within seconds, Nellie was down on the ground, horsewhipping the incredulous churl, whom she then summarily handed over to the police.

According to Daniel A. Goodsell, a Methodist bishop who summered on nearby Short Beach and wrote about local personalities in Nature and Character at Granite Bay (Eaton & Mains, 1901), while in her teens Nellie took control of the neglected family homestead and through her own self-discipline and strict attention to finances converted it into a productive enterprise.

Tragedy Takes its Toll

In 1890, the first of several family tragedies struck when Nellie’s younger brother drowned in the Farm River. Soon after, Nellie met Charles Hinckley, a railroad engineer six years her senior. After a brief courtship, the impetuous 16- or 17-year-old accompanied Hinckley to the altar. The young bride had bigger plans for her own life than merely being absorbed into the family businesses. Having taken voice lessons for years, Nellie spent the next five years traveling the East Coast as a mezzo-soprano with New York’s Savage and Whitney Opera Companies. Who knows how far her lovely voice might have taken her had not family tragedy struck again?

In October 1895, while Nellie was performing in Washington, her 28-year-old husband disappeared while fishing in Long Island Sound. No one knows exactly what happened, but after a week of frantic and futile searching, Hinckley’s bloated body finally washed ashore, where it was discovered by her distraught father.

Though Charles Green had been failing mentally for some years, the traumatic loss of his son-in-law apparently pushed him over the edge. Eventually he had to be placed in an institution, where he died in 1899. In the meantime, Nellie’s mother’s sight worsened to the extent that she was no longer capable of managing the family businesses. Nellie, now a young widow, had no choice but to abandon the stage and assume control of matters at home.

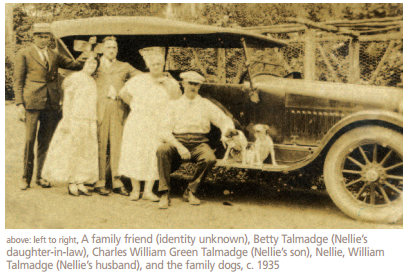

Within the year Nellie married William B. Talmadge, whom she had known since childhood. Scion of one of New Haven’s founding families, Bill was biding his time in the grain and feed business when he teamed up with the ambitious and indefatigable Nellie. Nellie had decided to build a hotel on her family’s property so as to capitalize on the growing popularity of Short Beach as a summer retreat, apparently using her inheritance to fund the project.

The Hotel Talmadge, a rectangular structure set adjacent to Branford Road (then known as Dyke Road, now Route 142) and perpendicular to the Farm River, opened in 1901 with 25 guest rooms, a restaurant, barroom, and marina. That same year, Nellie went into the maternity business, giving birth to her first—and only—child, a son christened Charles William Green Talmadge.

Over the next two decades, the Hotel Talmadge, which eventually became known simply as “Nellie Green’s,” thrived. Presiding behind the bar was “Old Iron Horse Nellie,” as one of her nicknames described her, bedecked in her trademark long riding coat and derby hat and carrying a riding crop, which she was not averse to using, particularly on anyone who violated the house rule forbidding coarse language. And though she was officially retired from the opera, she would occasionally regale patrons with renditions of operatic arias and sentimental Irish ballads such as “The Last Rose of Summer.”

To keep themselves busy during the off season, the Talmadges expanded into other lines of business. Bill oversaw operations of the Talmadge Boat Yard and the Talmadge Coal Company, which distributed locally the coal that arrived by barge at their dock. They also opened up their own soft-drink bottling company, the Old Bridge Beverage Company.

Their son Charles contracted polio in his early teens, and his doting mother was committed to providing him the best treatments and doctors that money could buy. It would turn out to be a protracted and expensive commitment.

Profiting from Prohibition

The 18th amendment, known as Prohibition, was signed into law in January 1919. As it didn’t take effect for another year, the now 46-year-old Nellie had ample time to weigh her options with regards to her hotel, restaurant, and bar business.

The 18th amendment, known as Prohibition, was signed into law in January 1919. As it didn’t take effect for another year, the now 46-year-old Nellie had ample time to weigh her options with regards to her hotel, restaurant, and bar business.

Though she probably could have weathered the storm financially by falling back on her other businesses, for reasons now unknown she decided to turn the Hotel Talmadge into a speakeasy. Being on the Farm River, just half a mile from Long Island Sound but not too close to the bright lights and scrutiny of New Haven, the hotel was ideally situated for landing and distributing the now-illegal hootch.

In 1920 East Haven had only 3,520 permanent residents, and the comings and goings of Nellie Green’s established dining, fishing, and boating clientele could mask those of its extralegal patrons. Nellie also had the local police, led by Constable Jim Smith, securely in her hip flask pocket. In fact, the police were among her most regular and loyal customers. Rumors eventually surfaced that Nellie was running a brothel. Nellie didn’t bother to squelch them, as prostitution was only a state crime and did not carry the same penalties—and risks to her career—as the federal crime of rum running.

In addition, the Talmadges’ other business would help launder their ill-gotten money, and having their own bottling plant on the premises would come in handy. Perhaps most importantly, those seven-foot tides that made routine navigation of the boulder-strewn Farm River estuary so challenging were now an undeniable asset. It took a steady and knowledgeable hand to negotiate the currents and eddies, especially at night, and Nellie had “Wing” St. Clair.

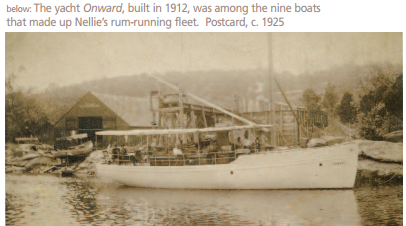

St. Clair, who would earn his nickname “Wing” by breaking his arm beaching a boat on Orient Point, Long Island in order to avoid the Feds, became the captain of Nellie’s initial three-boat rum-running fleet: Rosebud I, II, and III. The boats, all products of the Talmadge Boat Yard, were each 60 feet long with no decks and powered by two V12 Liberty surplus aircraft engines. They ran low in the water and could easily outrun anything the Coast Guard sent after them, especially over the three nautical miles that defined territorial waters back then, beyond which the Coast Guard had no jurisdiction

As per Nellie’s instructions, St. Clair and his men were never armed when they rendezvoused. St. Clair never got caught, but one of his lieutenants did. As Nellie was leaving for a vacation in New Hampshire, she drew her crew’s attention to the suspicious fact that several members of a new road-repair crew were wearing shoes that weren’t suited for that kind of work. Worried that they were undercover federal agents, she specified that no landing was to be attempted until the allclear signal was given. But after two days of idling offshore, the skipper of the “Sparkle” got antsy and came in anyway. The Feds caught him red-handed at the dock. But with Nellie out of town, Bill took the rap.

On another occasion, when tipped off about an imminent raid, Nellie’s crew buried the contraband in the cornfield behind the hotel, only to have several of the bottles explode in the summer heat. Another tale relates how, after years of futile lobbying, Nellie finally got the state to replace the old drawbridge across the Farm River. One day Nellie invited a barge crew from the quarry that was waiting for the tide to rise enough to propel their barge upriver to come in for a few drinks “on the house.” After making sure that their barge was tied up directly underneath the bridge, Nellie kept the drinks flowing until the men all passed out. Meanwhile, the tide came in, and the river lifted the barge up into the drawbridge, causing irreparable damage to the structure. The state reluctantly built Nellie her new bridge.

Nellie’s encounters with the authorities were minimal, and Prohibition proved to be a financial bonanza for her. She was able to indulge her lifelong passion for horses in a grand way by assembling a stable of thoroughbred show horses on a Branford farm she’d bought, with “Royal Flush,” a gelding, serving as her prize mount. Unfortunately, her son Charles also indulged his passion for horses. Though his limited mobility didn’t prevent him from taking a wife and fathering two sons, it did curtail his ability to help out around the inn. For amusement, he whiled away his idle hours at horse tracks, racking up considerable gambling debts. Still, Nellie continued to spend lavishly on doctors and treatments for Charles, bringing physicians in from as far away as California.

Nellie Green Goes Legit

With the repeal of Prohibition in December 1933, Nellie Green was once again a legitimate businesswoman and was now able to capitalize openly on her prodigious rum-running reputation. Though the country was by then in the grips of the Great Depression. Nellie Green’s, as the hotel was now officially called, continued to thrive as a legitimate, upscale rural retreat, especially for the “show biz” crowd. Among the big-name stars that came out to rusticate, often for weeks at a time, were Tyrone Power, Rudy Vallee, John Barrymore, and Bing Crosby.

Conditions in most of East Haven, however, were not as rosy. Many former “regulars” were now truly suffering, and Nellie saw that no one in genuine need went away hungry or without some coal to keep them warm. Though she preferred to do her charity by stealth, eyewitness accounts of Nellie’s generosity eventually leaked out from her many beneficiaries, including a hospitalized former bartender whose bills she paid and a down-on-his-luck laborer for whom she co-signed a $600 loan.

By the advent of World War II, Nellie, now in her 70s, had retired. After her son Charles died at home on October 6, 1942, her daughter-in-law, Betty, oversaw the operations of the hotel with Bunny Horton, an auto salesman and erstwhile friend of Charles’s, serving as restaurant manager. After Nellie’s death, Horton would begin booking the burlesque and sexually oriented acts for which Nellie Green’s would become infamous well into the 1970s.

By the advent of World War II, Nellie, now in her 70s, had retired. After her son Charles died at home on October 6, 1942, her daughter-in-law, Betty, oversaw the operations of the hotel with Bunny Horton, an auto salesman and erstwhile friend of Charles’s, serving as restaurant manager. After Nellie’s death, Horton would begin booking the burlesque and sexually oriented acts for which Nellie Green’s would become infamous well into the 1970s.

Nellie’s husband Bill died of a heart attack in January 1950. Nellie, who had also been suffering from heart ailments for more than a year, died on October 14, 1951 at the age of 78. The New Haven Journal-Courier paid front-page homage to the legendary innkeeper (the New Haven Evening Register ran its story on page 2), but, diplomatically, neither made reference to Nellie’s rum running and bootlegging, the very activities that had made her a local legend.

Nellie’s traditional Irish wake was held at the W. S. Clancy Funeral Home, the guest of honor laid out with an orchid pinned to her dress. On an unseasonably warm autumn afternoon two days later, she was buried between her husband and son in the Green-Talmadge plot in East Haven’s East Lawn Cemetery. A two-foot-high, roughhewn rounded tombstone marks her final resting spot.

In April 2006, veteran New Haven restaurateur Mike Savinelli opened a new establishment at the Branford Landing Marina and named it “Nellie Green’s” in honor of the legendary and inspirational fellow hospitality-provider. There is not, however, any physical or historical connection with the original “Nellie Green’s,” which in the late 1970s was converted into the Kelsey’s Landing condominiums.