By Donald Muller

(c) CT Explored, Fall 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

As to the Yankee clocks peddler…in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri and here in every dell of Arkansas and in every cabin where there was not a chair to sit on there was sure to be a Connecticut clock.

– G.W. Featherstonbaugh, English traveler in America, 1840

For much of human history, time and its measurement have been based on observation of the predictable travel of the sun through the sky, cycles of the moon, and the passage of the seasons. In recent centuries mankind has sought to measure time in smaller increments by observing the activity of such devices as burning oil, dripping water, graduated candles, and falling sand. In the mid-17th century the Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo (1564-1642) furthered this quest when he discovered that a pendulum’s swing takes the same amount of time regardless of the distance it travels and the weight of the bob at the end.

For much of human history, time and its measurement have been based on observation of the predictable travel of the sun through the sky, cycles of the moon, and the passage of the seasons. In recent centuries mankind has sought to measure time in smaller increments by observing the activity of such devices as burning oil, dripping water, graduated candles, and falling sand. In the mid-17th century the Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo (1564-1642) furthered this quest when he discovered that a pendulum’s swing takes the same amount of time regardless of the distance it travels and the weight of the bob at the end.

In 1656 Christian Huygens, a Dutchman, incorporated the pendulum’s periodic motion into a mechanical clock, improving its accuracy from within hours to within minutes per day. From that innovation sprang the modern clock- and watch-making industry. (Today we use the vibrations of the quartz crystal to measure thousandths of a second in races, and atomic clocks have an accuracy of .000000001 second per day.)

For the next century and half, clocks and watches made in Europe and the American colonies were hand crafted, with each part made and fitted separately. Innovation occurred over the next century, and by the late 1800s the clockmaking industry had helped establish Connecticut as one of the nation’s leading industrial areas. A century later, though, clock- and watch-making had all but disappeared from the state. That rise and fall is one of the state’s signature stories.

Eli Terry’s Innovation

Connecticut’s clock and watch industry traces its roots to 1773 when Thomas Harland (1735-1807), an English clockmaker, arrived in Norwich, Connecticut. He set up shop there, repairing watches and making clock movements with brass gears and finely engraved dials. From this small shop we can trace a direct line through the development of Connecticut’s clock industry.

Connecticut’s clock and watch industry traces its roots to 1773 when Thomas Harland (1735-1807), an English clockmaker, arrived in Norwich, Connecticut. He set up shop there, repairing watches and making clock movements with brass gears and finely engraved dials. From this small shop we can trace a direct line through the development of Connecticut’s clock industry.

Generally, clockmakers such as Harland produced the movement, which included the pendulum, the escapement or counting device, plus a series of brass gears to translate that count to clock hands whose changing positions were visible on the clock face. The movement, along with weights whose gravity-driven force supplied power to keep the clock running, was usually mounted in a tall wooden case purchased from a local cabinetmaker.

Harland’s production was greater than that of other clockmakers, and he had a large number of apprentices working under him. One of Harland’s apprentices, Daniel Burnap, set up business in what is now South Windsor, where he made many tall clock movements, including some with extraordinary musical chimes. One of Burnap’s apprentices was Eli Terry (1772-1852) from South Windsor, who forever transformed clock making from a craft to an industry.

During his apprenticeship Terry learned the craft of making brass movements in small quantities using foot-powered machinery. The molded brass gears had to be finished and fitted separately by hand, which was a time-consuming process. However, he was intrigued by the crude, and less expensive, wooden movements being made in East Hartford by Benjamin and Timothy Cheney.

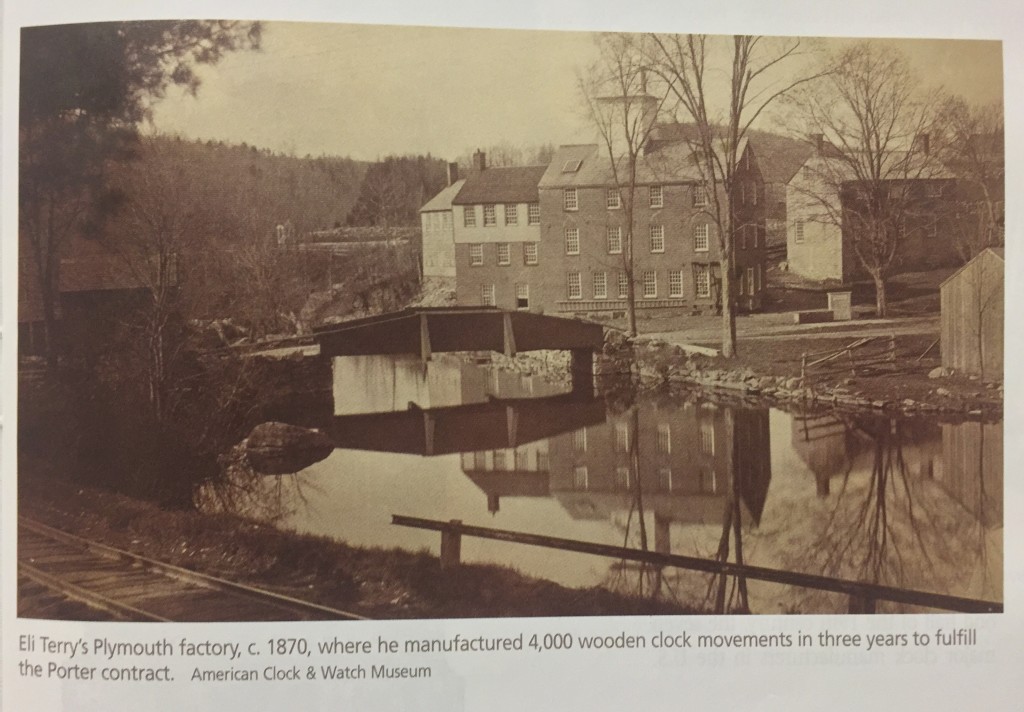

In 1793 Terry set up shop in present-day Plymouth, where he made both brass and wooden movements. By 1806 he had refined his wood movement using local hardwoods and begun to cut the teeth of the wooden gears with water-powered saws. Using wood, identical gears could be produced in quantity using less-skilled labor than was required to make brass gears. Since the parts were interchangeable, less time was needed for fitting. As a result, clocks with wooden gears were substantially cheaper.

Terry’s work came to the attention of Edward and Levi Porter, merchants from Waterbury, who in 1807 contracted with Terry to produce 4,000 tall-case wooden clock movements in three years. The Porters had identified an untapped market for clocks, but the astounding number was far beyond the capacity of any single clockmaker of the time.

Because he was paid part of the money up front, Terry was able to devote the first year to setting up his factory, making his machinery, and training his two workers, Silas Hoadley and Seth Thomas. They were able to refine their operation as they made 1,000 clocks in the second year; in the third year, having worked out all the kinks, they produced the remaining 3,000 clocks. The completion of the “Porter Contract” was the first successful large-scale production of a complicated mechanical mechanism with truly interchangeable parts—and an important American contribution to the Industrial Revolution.

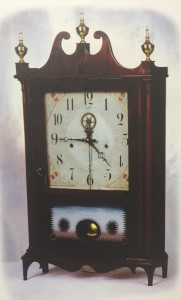

Eli Terry’s next innovation was the development of a wooden movement for a shelf clock, which allowed him to shorten the pendulum and decrease the distance needed for the weights to drop. The case could then be made small enough to sit on a shelf or mantel. This reduced the cost of both the movement and the case. Although Terry tried unsuccessfully to protect this innovation by patents, other local clockmakers soon were copying his movement and using it in the popular “pillar and scroll” model.

Eli Terry’s next innovation was the development of a wooden movement for a shelf clock, which allowed him to shorten the pendulum and decrease the distance needed for the weights to drop. The case could then be made small enough to sit on a shelf or mantel. This reduced the cost of both the movement and the case. Although Terry tried unsuccessfully to protect this innovation by patents, other local clockmakers soon were copying his movement and using it in the popular “pillar and scroll” model.

Peddling Time

As production increased and retail prices decreased, the next major challenge was expanding the market and getting the clocks to their potential customers. At first clockmakers peddled their own wares locally. Soon the Yankee peddler became the main distribution system. Connecticut-made clock movements and clocks were taken by foot, horseback, and wagon to individual farmhouses around New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and eventually the South and Midwest. Although farmers still relied mostly on natural cycles for telling time, they purchased clocks to demonstrate their financial success.

Local storekeepers and entrepreneurs such as the Porters in Waterbury and George Mitchell in Bristol played a critical role by purchasing the clocks from the clockmakers and hiring the peddlers to distribute them. Storekeepers also were able to accumulate enough capital to finance local clock manufacturing and innovations in design and production. Ready access to waterpower and abundant wood stimulated this expansion of clock making in Western Connecticut.

Rapid Growth in the Clock Industry

In the 1820s and 1830s, Bristol merchants, led by George Mitchell, encouraged the growth of the industry by recruiting clockmakers and case designers to settle in Bristol, where more than 280 clock manufacturers’ labels have been identified. Both skilled and unskilled workers migrated to the rural town, quickly changing it to an industrial center. By 1850, a third of Bristol’s residents worked in the clock factories; another third worked in support industries, and the remaining third was employed in other pursuits, including agriculture.

Although competition was intense, the growing United States population and the well-established Yankee peddler distribution system kept demand high and fueled a continuing string of innovations. In 1850 Connecticut clockmakers produced 511,000 clocks, with Bristol producing more than any other city in the state, making it the leading clock producing center in the country.

The increase in production spurred production of clock components including weights, bells, dials, painted tablets, and springs by small manufacturers. The presence of many small spring manufacturers in Central Connecticut today is an outgrowth of that phenomenon. Women often worked at home painting dials and tablets.

Brass Makes a Comeback

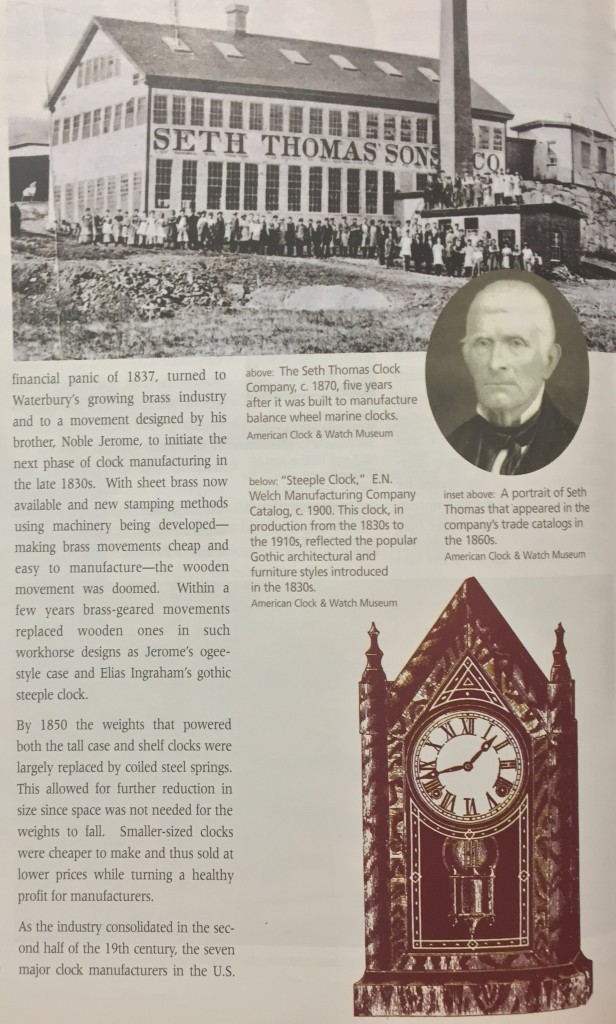

Throughout this period, clockmakers continued experimenting with hand crafting brass-geared movements but couldn’t produce them as cheaply as they could make wooden movements. Chauncey Jerome, a Bristol clock manufacturer whose wooden-movement factories were shut down by the financial panic of 1837, turned to Waterbury’s growing brass industry and to a movement designed by his brother, Noble Jerome, to initiate the next phase of clock manufacturing in the late 1830s. With sheet brass now available and new stamping methods using machinery being developed—making brass movements cheap and easy to manufacture—the wooden movement was doomed. Within a few years brass-geared movements replaced wooden ones in such workhorse designs as Jerome’s ogee-style case and Elias Ingraham’s gothic steeple clock.

By 1850 the weights that powered both the tall case and shelf clocks were largely replaced by coiled steel springs. This allowed for further reduction in size since space was not needed for the weights to fall. Smaller-sized clocks were cheaper to make and thus sold at lower prices while turning a healthy profit for manufacturers.

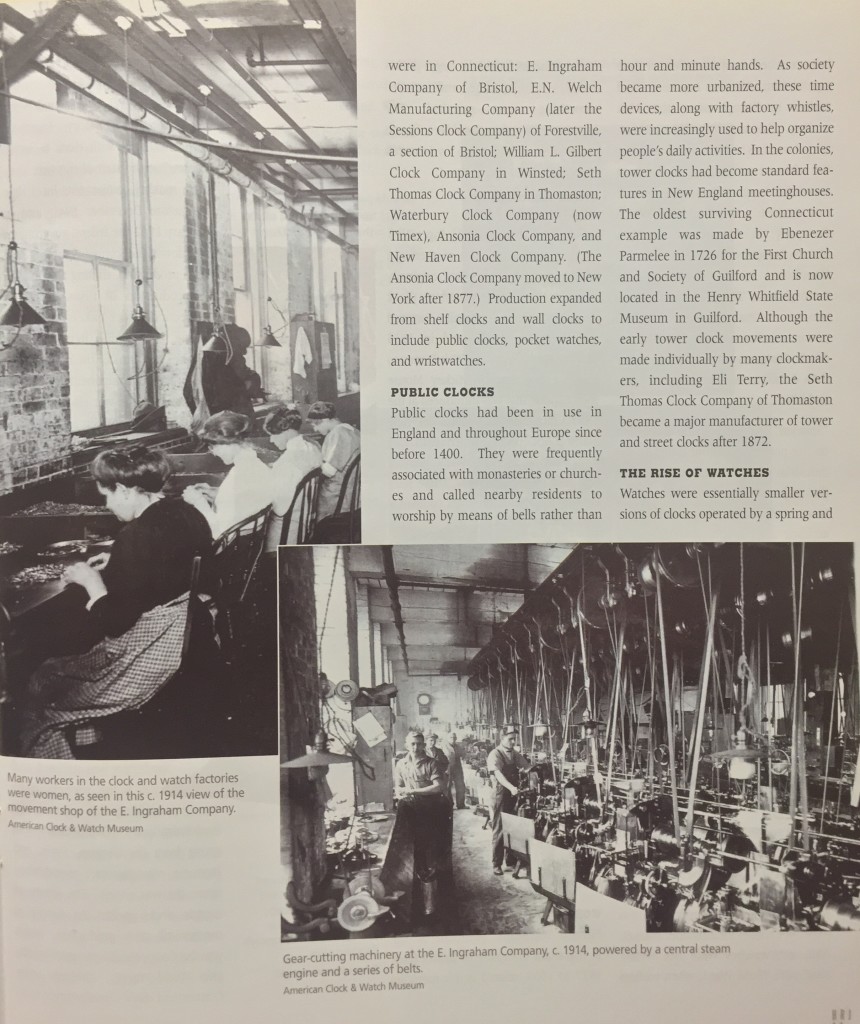

As the industry consolidated in the second half of the 19th century, the seven major clock manufacturers in the U.S. were in Connecticut: E. Ingraham & Company of Bristol; E.N. Welch Manufacturing Company (later the Sessions Clock Company) of Forestville, a section of Bristol; William L. Gilbert Clock Company in Winsted; Seth Thomas Clock Company in Thomaston; Waterbury Clock Company (now TIMEX), Ansonia Clock Company, and New Haven Clock Company. (The Ansonia Clock Company moved to New York after 1877.) Production expanded from shelf clocks and wall clocks to include public clocks and pocket-and wristwatches

Public Clocks

Public clocks had been in use in England and throughout Europe since before 1400. They were frequently associated with monasteries or churches and called nearby residents to worship by means of bells rather than hour and minute hands. As society became more urbanized, these time devices, along with factory whistles, were increasingly used to help organize people’s daily activities. In the colonies, tower clocks had become standard features in New England meetinghouses. The oldest surviving Connecticut example was made by Ebenezer Parmelee in 1726 for the First Church and Society of Guilford and is now located in the Henry Whitfield State Museum in Guilford. Although the early tower clock movements were made individually by many clockmakers, including Eli Terry, the Seth Thomas Clock Company of Thomaston became a major manufacturer of tower and street clocks after 1872.

The Rise of Watches

Watches were essentially smaller versions of clocks operated by a spring and balance wheel escapement rather than a pendulum. Watches had been hand crafted in Europe since the 15th century. Successful machine production of watches in the United States was not achieved until after 1850. The most successful watchmakers were outside Connecticut: the Waltham Watch Company in Massachusetts, Elgin Watch Company in Illinois, and The Hamilton Watch Company of Pennsylvania. The only Connecticut concern to make quality “jeweled” pocket watches was the Seth Thomas Clock Company, which made more than 4 million watches between 1882 and 1915.

“Jeweled” refers not to the decoration on the pocket watch but rather to the industrial minerals used as bearings in the major pivot holes, which reduce wear and make the watch more accurate and durable. As the railroad system in the country expanded, conductors needed these highly accurate pocket watches to maintain schedules and avoid train crashes. Standard time zones were established in 1883 at the urging of those same railroad companies. Victorian men bought expensive pocket watches for themselves but often bought cheaper watches that served mostly as jewelry for their wives; after all, they believed, women did not really need to know accurate time.

Jeweled pocket watches were often too expensive for the working class, so Connecticut clock manufacturers, including Waterbury, E. Ingraham, and New Haven, pushed to produce a less expensive model for a broader market. Still, wristwatches were not widely used until World War I, when soldiers in the trenches found the larger pocket watches cumbersome and needed something more practical. The Ingraham, Waterbury and New Haven companies moved into wristwatch production after World War I.

TIMEX Becomes a Household Name

A New York company, R.H. Ingersoll & Brother, was famous for marketing a “dollar watch,” which was originally made for them by the Waterbury Clock Company. The Ingersoll-Waterbury Company survived the Great Depression and in 1933 reached agreement with Walt Disney to create a new line of Mickey Mouse merchandise that was introduced at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The new alarm clock, pocket watch with fob, and wristwatch were wildly popular and sold by the millions. These sales revived the almost bankrupt company.

A New York company, R.H. Ingersoll & Brother, was famous for marketing a “dollar watch,” which was originally made for them by the Waterbury Clock Company. The Ingersoll-Waterbury Company survived the Great Depression and in 1933 reached agreement with Walt Disney to create a new line of Mickey Mouse merchandise that was introduced at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The new alarm clock, pocket watch with fob, and wristwatch were wildly popular and sold by the millions. These sales revived the almost bankrupt company.

In 1941 a group of Norwegian investors purchased a controlling interest in the revived Waterbury Clock Company and in 1943 changed the name to The United States Time Corporation. In 1950 the company began making an inexpensive watch with a “Timex” movement, which became popular in part because of television ads featuring newsman John Cameron Swayze and the slogan, “It takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’.” The Timexpo Museum in Waterbury tells the story of this company in detail.

World War II Production

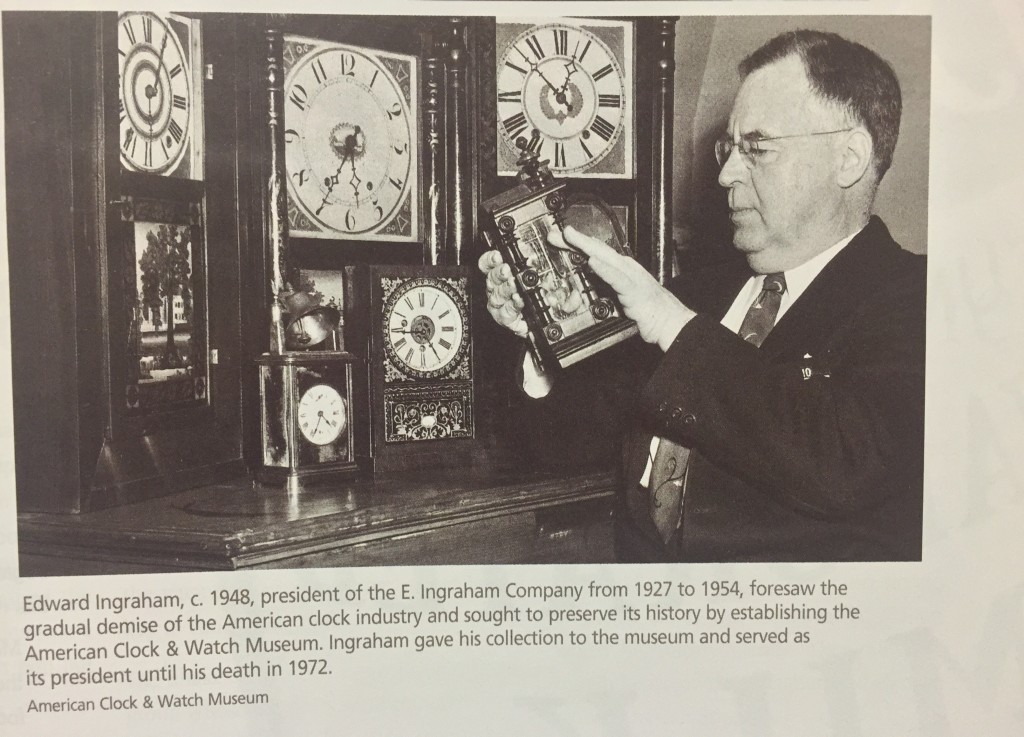

Edward Ingraham, president of the E. Ingraham Co. in Bristol from 1927 to 1954, related in his memoirs that the company, facing labor and material shortages, did not do any war work during WWI. The Second World War was a different story. Ingraham Co. was “swamped with clock & watch business” at the start of the war. They began making components for a time fuse before December 1941, and in February 1942 the federal government shut down the company’s clock and watch production, shifting resources to the production of fuses. Although Connecticut clockmakers were not making high-profile items such as airplanes or tanks, their small but high-precision components were also important for the war effort. By April 1942 the company employed 1,800 persons and made 60,000 fuse plates per day. The company also made artillery fuses and other components. They made more than 900 million fuses and fine precision parts by 1945.

The Clock Industry Closes Down

After World War II the American clock and watch industry could not regain its pre-war position. The companies had lost their trained workers, their suppliers, and their customers to foreign competition. Their machinery was outdated, and some owners were unwilling to invest in modernization. Competition was strong from the German, Swiss, and Japanese manufacturers reestablished when the war ended. . The advent of electric clocks spelled the demise of mechanical clock production, which was the Connecticut companies’ staple, after World War II. Although some Connecticut clock manufacturers were able to produce a reliable electric clock by 1929, they were unable to keep up with the post-war competition. Conglomerates or foreign investors purchased several of the Connecticut firms. The Connecticut manufacturers were downsized, and one by one their factories closed.

Although most production has moved overseas, The United States Time Corporation, now called TIMEX, still operates its worldwide business from its headquarters in Middlebury, Connecticut. Today, some clocks are still being made with the Seth Thomas or Ingraham name. But wristwatch sales have decreased as people have ready access to the time on computers, cell phones, and other ubiquitous electronic devices.

During the “Golden Age” of clock manufacturing, from 1880 to1920, companies from western Connecticut employed tens of thousands of local residents, sold millions of clocks and watches to both domestic and foreign markets, and spread the state’s name into households everywhere. Today this important industry has disappeared from the local scene.

Eli Terry’s shelf clock, c. 1818, was the first to be produced in quantity. American Clock & Watch Museum

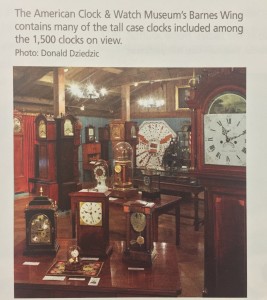

Fortunately, Edward Ingraham of Bristol had the foresight to initiate the formation of The American Clock & Watch Museum in 1952. The museum preserves the story of this important part of Connecticut’s heritage in Bristol, where much of the story developed. Visitors can see more than 1,400 clocks and watches on display. including “grandfather” clocks, shelf clocks, wall clocks, precision regulators, novelties, alarm clocks, tower/church clocks, jeweled watches, watch keys and fobs, non-jeweled or “dollar” watches, clock and watch making machinery and tools. Many are kept running and chimin

Donald Muller was the executive director of the American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol.

Explore!

“TIMEX: Takes Licking and Keeps on Ticking”

Read more stories about products made and invented in Connecticut on out TOPICS page.

The American Clock & Watch Museum

100 Maple Street, Bristol

(860) 583-6070, www.clockmuseum.org