By Walter Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2014-2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

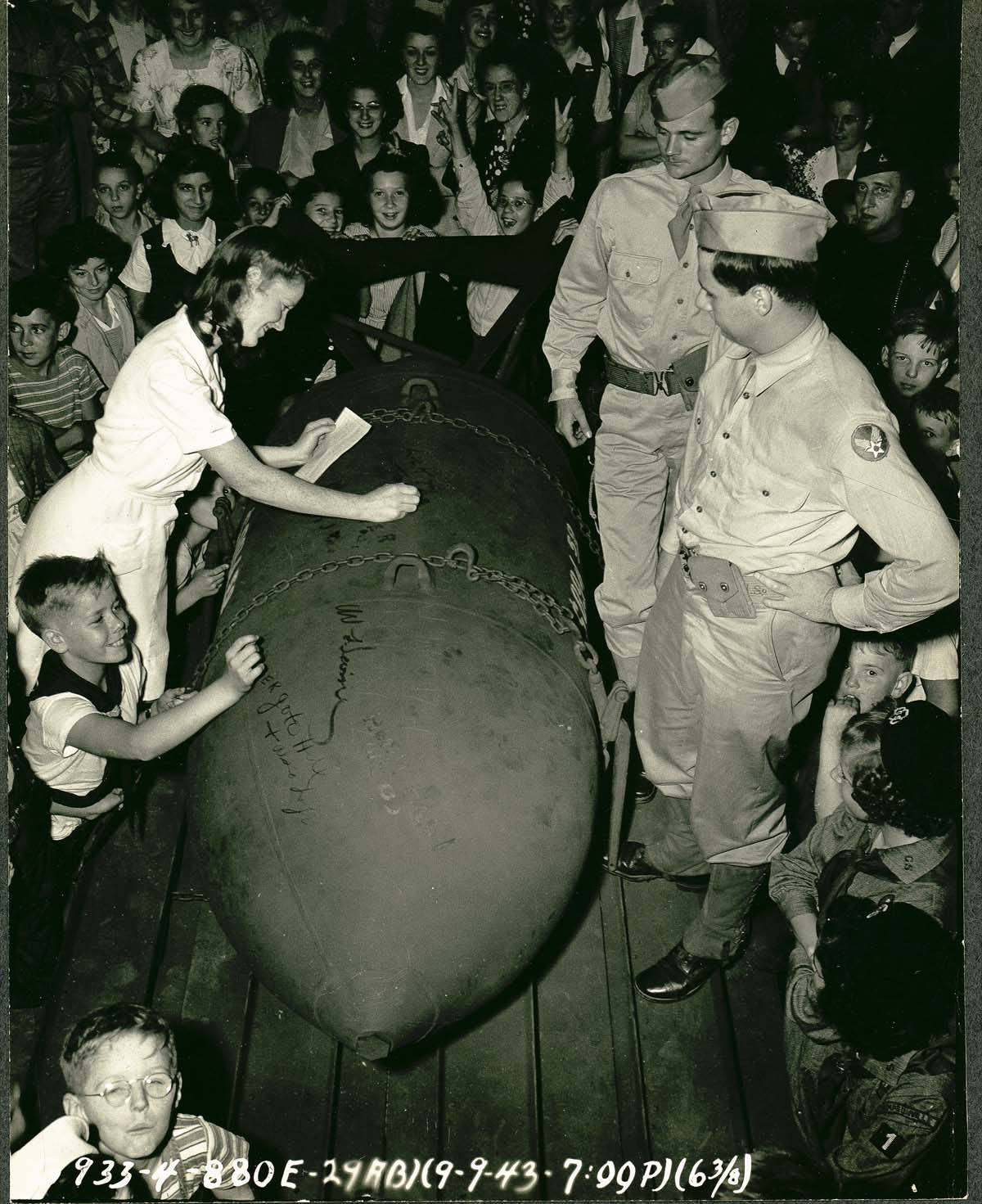

Children write messages on a blockbuster bomb, September 9, 1943. U.S. Army Air Corps, State Archives, Connecticut State Library. Used with permission.

This image, taken at Bradley Airfield in Windsor Locks on September 9, 1943, gives one pause. It shows happy school children signing a 4,000-pound blockbuster bomb—the same kind as was used so effectively against German cities and civilians in World War II—under the approving glances of both teachers and military officials. It underscores just how different the attitudes of America’s Greatest Generation (to use journalist Tom Brokaw’s term) to war were compared to our own more conflicted and ambiguous feelings, even as it asks us to consider what the experience of World War II was like for their children.

From the attack on Pearl Harbor to V-J Day (Victory over Japan) and beyond, World War II was a disruptive and deeply stressful time for the kids of Connecticut. Fears of both domestic attack and the combat death of relatives, the long-term absence of fathers on war duty, and the simultaneous entry of mothers into the defense work force, food rationing that made everyday items scarce luxuries, acute housing shortages, and high mobility—all exacted a persistent and high psychological cost on parents and children alike. “War jitters” became a common medical problem, and authorities noted that children often bore the brunt of the war’s dislocating forces. “The Hartford boy or girl roaming the streets because his or her home no longer functions as such is as true a war casualty as the wounded soldier in Tunisia,” noted Clara Dean Marshall, special agent of the Connecticut Humane Society, in a 1943 radio broadcast on Hartford’s WTIC.

Children were encouraged by government, school officials, teachers, and parents to alleviate the anxiety caused by the war through intense patriotism and meaningful participation in the war effort. The Children’s Salvage Army, formed in August 1942, recruited Connecticut students to join in a nationwide house-to-house canvas collecting scrap metal. One old flatiron doorstop could produce 30 hand grenades, the children were told; a leaky bucket could be turned into three bayonets, according to an August 30, 1942 Hartford Courant article. In Manchester alone, tin-can drives netted 65,095 tons of metal between November 1942 and June of 1943. The Schools at War Program, headed in Connecticut by the state’s first lady Edith Baldwin, engaged students in multiple campaigns to buy and sell War Savings Stamps, grow victory gardens, and conserve and collect materials needed for war production. Children were even asked to collect milkweed pods from roadsides and fields to be used in making life jackets for sailors and aviators.

Throughout World War II, the nation’s anxious children were told that their efforts were essential parts of a global war of good against evil. In that context, an eight-year-old’s signing a bomb with the message “Hitler go to hell, and also Japs” might be considered just one more contribution to the victory.

Throughout World War II, the nation’s anxious children were told that their efforts were essential parts of a global war of good against evil. In that context, an eight-year-old’s signing a bomb with the message “Hitler go to hell, and also Japs” might be considered just one more contribution to the victory.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut state historian. For information about upcoming talks he is giving visit the Office of the State Historian’s Web site at cthistory.org.

Explore!

Read more stories about Childhood and Connecticut at War on our TOPICS pages.