(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Abraham Lincoln made his only visit to Hartford on March 5, 1860. Historians have little noted what he said here, perhaps because his Hartford speech was overshadowed by a weightier address he gave in New York a week before. Then, too, Lincoln ‘s Hartford remarks were in some respects a rough draft of a longer, more polished speech he made in New Haven on March 6. Yet the Hartford speech warrants attention: It offers invaluable glimpses of Lincoln as both prophet and pragmatist, the unique mix of qualities he revealed nowhere more tellingly than he did here.

In 1860 the American republic was disintegrating. Fractures and frictions were everywhere: North vs. South, whites vs. blacks, Republicans vs. Democrats. In his speech at Hartford ‘s City Hall Lincoln somberly analyzed the national crisis. But instead of bowing to the reigning rancors of the day, he urged a spirit of humility and conciliation. He would restore the country’s unity and stability by returning to its original promise—as he saw it—of becoming a just democratic society. In his first inaugural address, a year after his appearance in Hartford, Lincoln said the broken United States would be healed when Americans were “again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Dark though it was, Lincoln’s Hartford speech was really about those angels.

Lincoln stopped in Hartford in the middle of the eastern tour that put him on the road to the presidency. Before coming east he was a western favorite son who doubted his own fitness for high office. During his Illinois debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858, Lincoln made a joke of his wife’s prediction he would one day reach the White House: “Just think of such a sucker as me as President!” His 1860 swing through New York and New England changed all this. It gave him national stature, and he knew it. Back in Illinois, when asked whether he had presidential aspirations, Lincoln now confessed, “The taste is in my mouth a little.”[1]

In truth this appetite for the presidency was one of the reasons Lincoln came east in the first place. He wanted to visit his son Robert at Phillips Academy in New Hampshire , but his chief aim was to make a name for himself in the backyard of the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination, New York Governor William H. Seward. So when a group opposed to Seward invited Lincoln to speak in New York in late February 1860, he eagerly accepted. This speech, at Cooper Union, proved a turning point in his career. A scholarly exposition of moderate anti-slavery principles, it was greeted with adulation. Four newspapers ran the full text of the speech the following morning. From this triumph Lincoln proceeded to New Hampshire , where he spoke several times before arriving in Hartford the afternoon of March 5.

The political season of 1860 was already blazing hot. New Hampshire voters were scheduled to elect state officers on March 13, which is one reason Lincoln spent several days there. In Connecticut the approaching spring elections featured the incumbent Republican governor, William Buckingham, running against the Democratic challenger, Thomas Seymour. Both major parties agreed that even in this state where slavery was extinct, the great issue was the future of slavery. “… Avote this spring in Connecticut for Thomas H. Seymour, is a vote for slave labor in the territories,” roared the pro-Republican Daily Courant. The fiercely Democratic Daily Times painted its Republican foes in the stripes of John Brown, the abolitionist who had been hanged for trying to foment a slave insurrection in Virginia the previous year. “The John Brown … party will not elect the next President!” the Times swore the day after Lincoln ‘s Hartford appearance. “That is as fixed as fate.”[2]

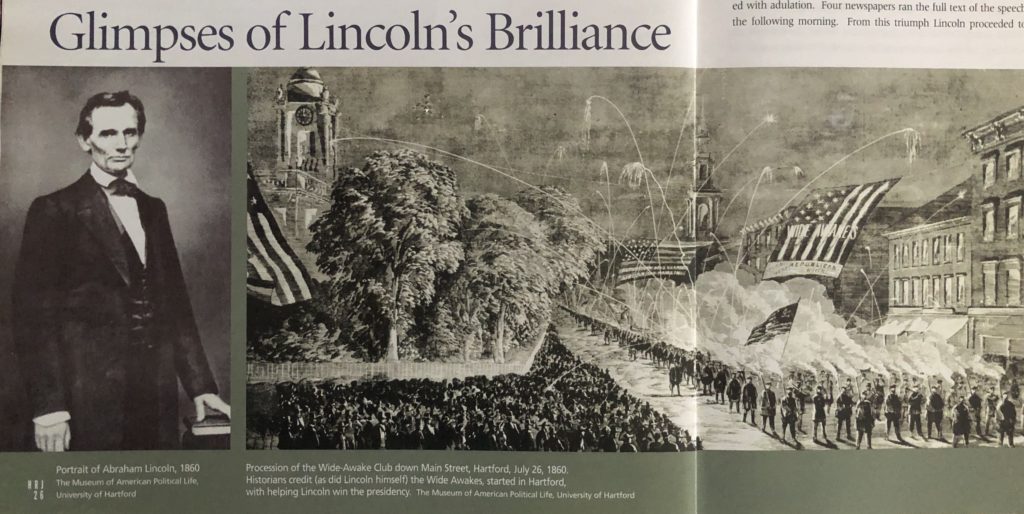

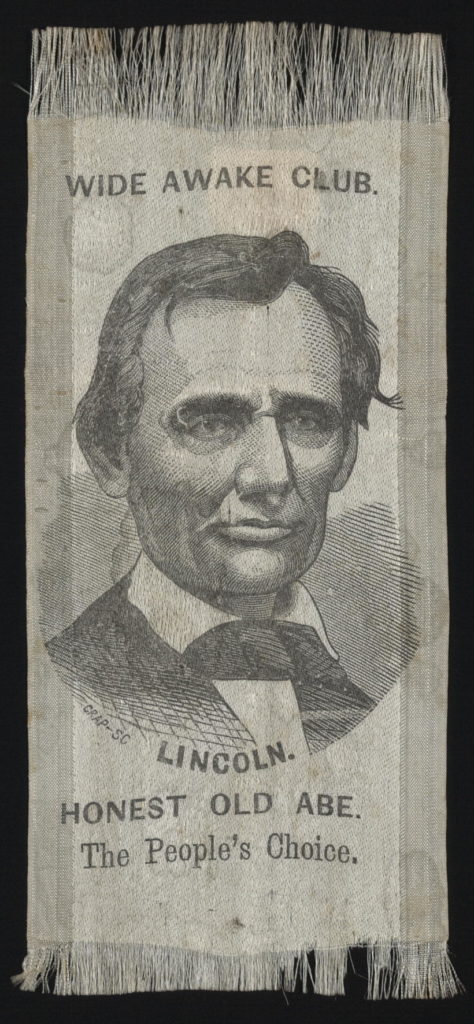

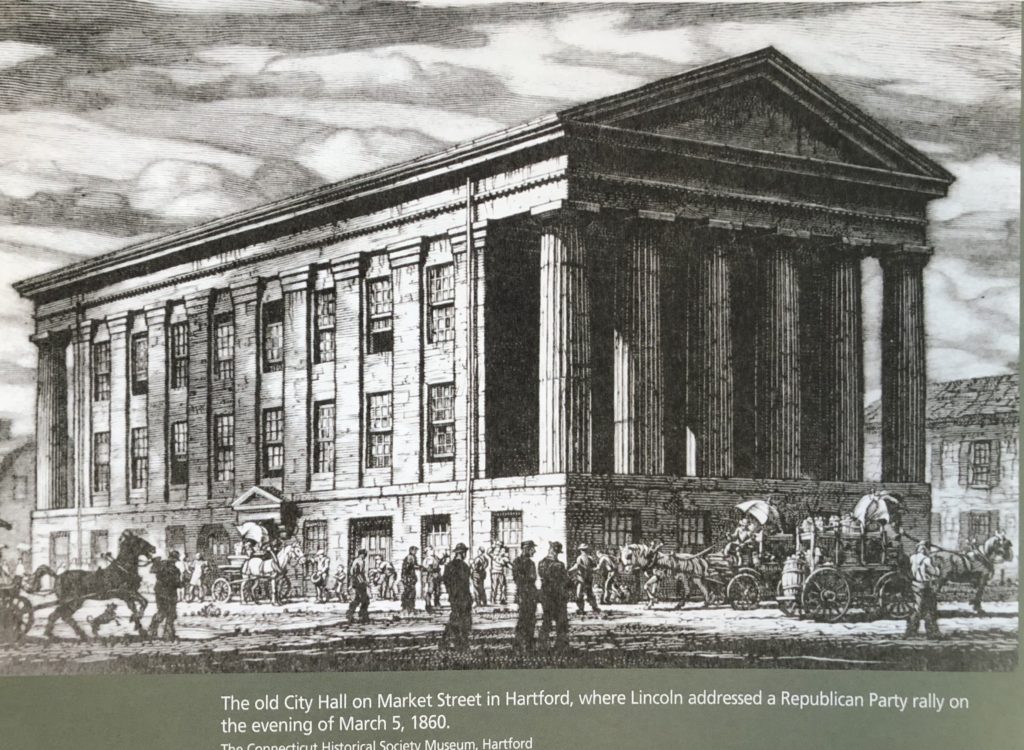

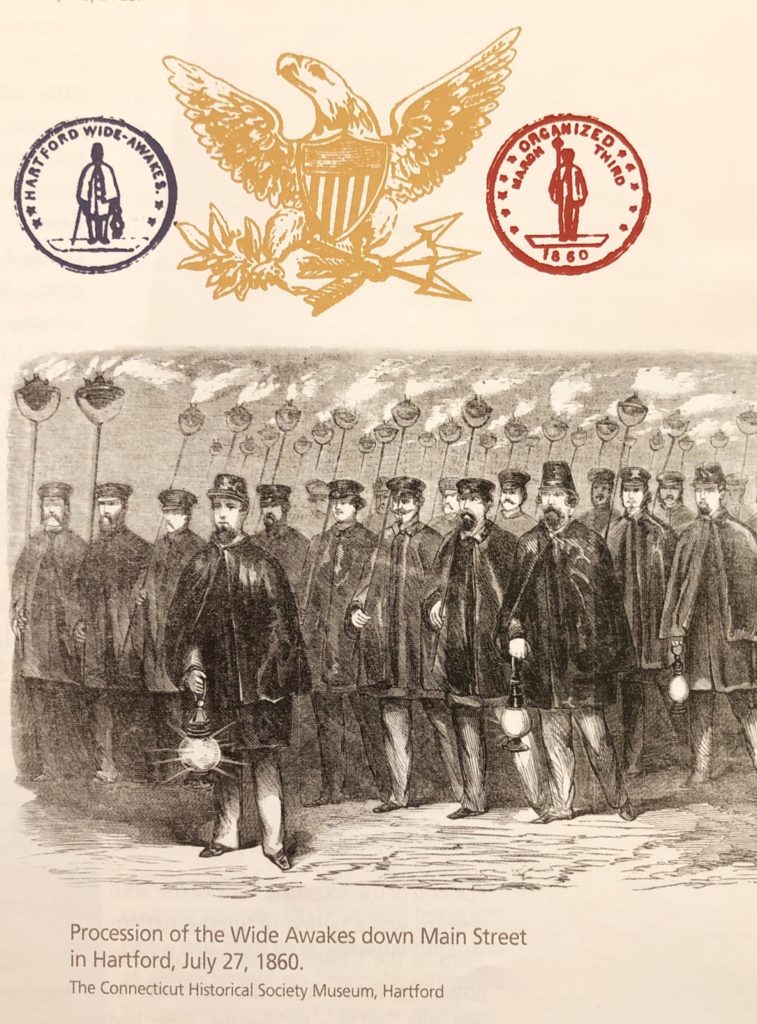

Nineteenth-century politics mingled solemnity with pageantry and circus. Hartford rolled out all its best hoopla for “Abram” Lincoln, as both the Courant and the Times sometimes called him. Just hours after getting off the train that brought him here on March 5, Lincoln was ushered to City Hall (then on Market Street ) where an overflow crowd awaited him. He spoke for more than two hours from a few lines of notes, closing with a version of the spine-tingling call he had used to end his Cooper Union address a week earlier: “… let us have faith that Right, Eternal Right makes might, and as we understand our duty, so do it!” A reported “thousand marchers” then escorted Lincoln on the short carriage ride to the home of Mayor Timothy Allyn on Trumbull Street, where he was to stay the night. Leading the torchlight procession were the Hartford Cornet Band and the black-caped “Hartford Wide Awakes,” a Republican youth organization (formed just days before) whose membership would soon spread throughout the Northern states.[3]

Behind the spirited shows and ceremonies of this electoral season, however, lay swelling anxieties about the country’s future. Antagonisms between the slaveholding South and the free-labor North had jeopardized the Union ever since the republic’s creation. Those clashing interests had erupted into crisis many times, but always the division had been papered over. By 1860 the country appeared to be approaching a climactic rupture that could not be patched by compromise. The new and growing Republican party was determined to check the spread of slavery. Democrats insisted on white men’s right to hold slaves anywhere local laws permitted the practice. New York Governor Seward spoke of “an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces [that]means that the United States must and will … become either entirely a slave-holding nation, or entirely a free-labor nation.”[4]

Predictably, the Hartford press viewed Lincoln’s visit through thick partisan lenses. The Courant called his speech “the most convincing and clearest we ever heard made,” with its message that any extension of slavery should be staunchly opposed. The Times—pandering to images of Lincoln as a country bumpkin-reported the visitor had had to apologize “for the slovenliness of his personal appearance, and for not even having changed his linen.” As for Lincoln’s mind, the Times accused him of having just “One Idea—Abolition and Nothing Else.”[5]

Americans would eventually learn that Lincoln did not fit neatly into any pigeonhole. His Hartford speech, like so many of his utterances, transcended the hurly-burly of current events; it struck notes too deep for partisans or journalists to hear. Lincoln’s audience at City Hall came to attend a Republican rally featuring a gangly stranger who might, they thought, be a dark-horse possibility for the vice presidency. They could not know they were getting a privileged look into the mind of the profound statesman who in less than a year would be leading the country through the most painful and most formative episode in its history.

Though Lincoln ‘s Hartford address was not the obsessive “Abolition Harangue” the Times labeled it, forthrightly anti-slavery it certainly was. Lincoln called slavery a “great evil,” “the all-prevailing and all-pervading question of the day.” At one point he compared the South’s “peculiar institution” to a rattlesnake; at another he likened slavery to a wen on a man’s neck, terrible to live with but possibly fatal to cut out. Sounding like Governor Seward in his famous “irrepressible conflict” address, Lincoln warned Hartford that slaveholders would never be satisfied with mere tolerance of their practices. They demanded the country affirm slavery as both lawful and right. Eventually the South would press the North “to yield the guards of liberty in our state constitutions… .” Thus the nation stood at a dreadful impasse. “If slavery is right, it ought to be extended; if not, it ought to be restricted—there is no middle ground.”[6]

Why, Lincoln asked, if no one wanted to see slavery split the country, did the question remained unsettled? One reason, he suggested, lay in the “great mistake” of underestimating the economic dimension of the question. One-sixth of all Americans were slaves. “Those who own them look upon them as property, and nothing else. The entire value of the slave population of the United States , is … not less than $2,000,000,000. This amount of property has a vast influence upon the minds of those who own it.” The slaveholders’ financial investment in slavery blinded them to its injustice, he suggested. “When you tell them that slavery is immoral, they rebel, because they do not like to be told they are interested in an institution which is not a moral one.” Putting their material interests foremost, Southern slaveholders favored any policy that “secures them property in the slave.[7]

City Hall, Market Street, where Lincoln addressed a Republican Party rally, March 5, 1860. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

“Now this comes in conflict,” Lincoln pointed out, “with [the]proposition that we at the North view slavery as a wrong. We understand that the ‘equality of man’ principle which actuated our forefathers in the establishment of the government is right; and that slavery, being directly opposed to this, is morally wrong… .”

So the sectional conflict pitted greedy, amoral Southerners against idealistic, righteous Northerners, Lincoln seemed to be saying. This was how Governor Seward too framed the conflict, according to a speech the Courant had reported just two days earlier. The crisis over slavery turned on “an economical question,” Seward said, that was also a moral one. Whereas a slave state extinguishes the personality of the laborer, a free state “encourages and animates and invigorates the laborer… . In the one case, capital invested in the slaves becomes the dominating political force, while in the other labor thus elevated and enfranchised becomes the dominating political power.”[8]

But the apparent similarity between Lincoln ‘s position and Seward’s was deceptive. Seward pictured an absolute contrast between Southern venality and Northern enlightenment. Lincoln acknowledged a difference, but then (despite what he had said) set about seeking a “middle ground” on which the sections could begin to understand each other. Two billion dollars—the wealth Southerners had invested in slaves—would exert “a vast influence” on anyone, Lincoln observed. “The same amount of property owned by Northern men has the same influence upon their minds. We do not assume that we are better than the people of the South—neither do we admit that they are better than we… .” Anti-slavery Northerners could afford to take a moral view of slavery because they had no economic stake in it, but this did not necessarily make them morally superior. The case was more complicated than that. “Almost every man has a sense of things being [right or]wrong, and at the same time a sense of [their]pecuniary value. These conflict in the mind, and make a riddle of a man.”[9]

Here was an interpretation of the national crisis that soared above the wrangling and sniping of March 1860. Why was the slavery malignancy so hard to cure? Because, Lincoln argued, it was not the product of a wickedness unique to slaveholders. Nor was slavery a bizarre anachronism standing in the way of the nation’s economic growth. To the contrary, Lincoln identified slavery with the driving engines of that growth. That was exactly the problem: In their zeal for material progress, all Americans, North and South, were losing their moral bearings. Southerners held slaves, and many Northerners tolerated the practice, because “pecuniary value” had become their ruling value.

The most fundamental division in American life was not, then, the Mason-Dixon line. It was the “conflict in the mind” of every man between greed and conscience. Too many white Americans were resolving this inner conflict-they were solving the “riddle” of their divided desires—by sacrificing their sense of right and wrong to calculations of dollars and cents.

Procession of the Wide Awakes down Main Street, Hartford, July 27, 1860. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Lincoln not only thought the riddle was unsolvable but that it was a mistake to think it solvable. Tensions between material and moral motives were built into human nature. The sooner Americans accepted the fact that they were all riddles—all imperfect, contradictory creatures—the sooner they could recognize their common needs and their common destiny. “We do not assume that we are better than the people of the South.”

In 1860 few Americans were receptive to this healing message. Unsurprisingly, the Courant missed the message altogether. Lincoln’s main point, the paper commented on March 6, was to call on Northerners to confine the slavery evil “to its shelter within the Southern states, and wash the hands of the nation of all contamination with its guilt”—in other words, to demonize the white South.

If the editors of the Courant did not hear Lincoln ‘s plea for mutual understanding among white Americans, they were stone deaf to his views of black Americans. In the same March 6 edition that reported Lincoln ‘s address, the Courant made plain it opposed slavery largely because it opposed blacks. “…Shame on the free laborer of the North, who has not courage enough to help confine the negroes where they belong, in the Southern States. The territories must be preserved for the SONS OF WHITE MEN. A vote for BUCKINGHAM, is a white man’s vote; a vote for Seymour is a vote for MORE NEGROES.”[10] (One can only imagine what this sounded like to members of Hartford’s small but vibrant African American community [who had been disenfranchised in the state’s Constitution of 1818].)

In the matter of racial attitudes Abraham Lincoln was no angel. He came from Illinois, a ” free state” that viciously restricted the freedom of black people. And so it is not surprising to discover that Lincoln sometimes made casual use of the “n” word. In his Hartford speech, for example, he pointed out that in the minds of some people, “when the question is between the white man and the nigger, they go in for the white man; when it is between the nigger and the crocodile, they take sides with the nigger.” But here Lincoln was paraphrasing views that he emphatically rejected. In New Haven the next day, Lincoln called the white man-black man-crocodile comparison a slander devised to “brutalize the negro, and to bring public opinion to the point of utter indifference whether men so brutalized are enslaved or not.” The epithet “nigger” belonged to the vocabulary of those who thought slavery a matter of “dollars and cents, only.”[11]

When speaking in his own voice Lincoln almost always referred to African Americans as “negroes” or “blacks,” and what he had to say about them defied the commonplace prejudices of his day. Put simply, Black people were Americans, to whom the pledges of the Declaration of Independence applied just as they did to whites. Blacks too were “created equal,” they too possessed “unalienable rights” to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Lincoln insisted these were the convictions of the founding fathers, all of whom opposed slavery and wished and expected it to wither away. Democrats who denied the Declaration included Blacks were betraying the founders’ vision, Lincoln argued.

Lincoln ‘s interpretation of the founders’ intentions may have been fanciful, but his own intentions were not. He called for closing the distance between whites and Black people in the same spirit of conciliation and inclusion he urged for the resolution of conflicts among whites. The Declaration of Independence provided Americans with a lofty “middle ground” on which all could meet, if they could muster the courage and wisdom to climb to it.

Lincoln did not propose to eliminate the color line in American society. In 1860 scarcely anybody was ready for that. He was, however, moving beyond the safe anti-slavery position of Seward and other leading Republicans. They stood for emancipation only. Lincoln was beginning to contemplate authentic citizenship for Black Americans.

In Hartford Lincoln touched on these notions as he briefly sketched his ideal of a just America. For example, he affirmed that “… the free states carry on their governments on the principle of the equality of men… . Every man, black, white or yellow, has a mouth to be fed and two hands with which to feed it—and that bread should be allowed to go to that mouth without controversy.” It was in New Haven the next day, however, that Lincoln presented his vision in concrete terms unmatched anywhere else in his matchless oratory. Referring to an ongoing strike by New England shoemakers, Lincoln asked the white workers of Connecticut to wish for Black Americans what they valued for themselves, a free-labor system “where they are not obliged to work under all circumstances, and are not tied down and obliged to labor whether you pay them or not! I like the system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere.”[12]

Lincoln then declared his personal solidarity with workingmen, white and Black alike. “When one starts poor, as most do in the race of life, free society is such that he knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor… . I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat-just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have a chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition—when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system.”

“I want every man to have a chance..”So do we all, Lincoln ‘s listeners would say, presuming “every man” were white. But “a black man is entitled to it”? In a white-supremacist country on the verge of warfare over slavery, this was supremely audacious. Lincoln was telling his audience they lived in a revolutionary country whose “true system” was an all-inclusive democracy. This anchoring conviction would lead him to issue the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, to begin advocating Black suffrage in 1864, and finally to call for binding up “the nation’s wounds” caused by “American slavery” a month before his assassination in 1865.

Amid the local electoral hullabaloo surrounding the race between Republican Buckingham and Democrat Seymour, amid the overwhelming national strife of 1860, it is doubtful many people who heard Lincoln in Hartford or in New Haven fully grasped his vision. But then it is doubtful many Americans ever have.

Gene Leach is a professor of history at Trinity College and a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial board.

Explore!

“When Norwich Celebrated the Emancipation Proclamation,” Winter 2012-2013

Connecticut in the Civil War, Spring 2011

150th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation Winter 2012-2013

Read more stories about Connecticut at war on our TOPICS page.

Footnotes

1. David Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 235, 241.

2. Daily Courant , Hartford , March 6, 1860; Daily Times , Hartford , March 6, 1860.

3. Lincoln’s visit is colorfully described in “Lincoln in Hartford,” a pamphlet by J. Doyle DeWitt “privately printed in support of the activities of the Connecticut Civil War Centennial Commission,” Connecticut Historical Society.

4. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 198.

5. Daily Courant, March 6, 1860; Daily Times, March 6, 1860.

6. Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953), IV:2, 5-6, 13.

7. Ibid., IV:3.

8. Daily Courant , March 3, 1860.

9. Basler, ed., Collected Works , IV:3.

10. Daily Courant , March 6, 1860.

11. Basler, Collected Works , IV:4, 20.

12. Ibid., IV:9, 24-25.