By Alexis Rankin Popik SUMMER 2005

Hartford has long been a city of “firsts.” The first federal law book was published in Hartford and the first witch to be convicted was hanged here as well. Of the nearly one hundred “firsts” that Hartford can claim, one is particularly germane today: Hartford Seminary is the site of the country’s first center for the study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. How the Seminary, founded in 1834 by feuding Calvinists, came to include a world-renowned center for inter-religious understanding is a little-known element of Hartford’s history.

Hartford has long been a city of “firsts.” The first federal law book was published in Hartford and the first witch to be convicted was hanged here as well. Of the nearly one hundred “firsts” that Hartford can claim, one is particularly germane today: Hartford Seminary is the site of the country’s first center for the study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. How the Seminary, founded in 1834 by feuding Calvinists, came to include a world-renowned center for inter-religious understanding is a little-known element of Hartford’s history.

Religion was central to early Connecticut. Politics, education, and economics were inextricably tied to the Congregational Church since, until 1818, the Church was the official, tax-supported religion of the state.

Nevertheless, from the earliest days there were conflicts in doctrine among Congregationalists, with all parties claiming to represent true Calvinist orthodoxy. In the spring of 1831, one of these controversies arose in the midst of an unprecedented revivalist movement. The revivals took two forms: those conducted by local pastors in their own churches and those carried on by young, itinerant evangelists who were opposed by the established ministry. Of the state’s 226 Congregational churches, 80 percent experienced revivals. In 1832, eight thousand new members joined the church. Yale College was greatly affected, and a large number of students there joined the movement. Concern grew among local pastors that the new converts did not truly understand the faith and could not be considered legitimate believers.

In the midst of this turmoil, a theological controversy erupted and led to the establishment of an alternative seminary to Yale. The dispute, called “The Taylor-Tyler Controversy,” concerned the nature of sin. The two groups of Calvinists involved came from different areas of the state, East Windsor and New Haven. Professor Nathaniel W. Taylor of Yale College took the progressive position that sin began after birth. Reverend Bennet Tyler, leading the East Windsor faction, maintained the conservative Calvinist stance that through the sin of Adam, human nature was essentially depraved. Though their theological difference seemed minor to later generations, the controversy was long-lived and heated. An anonymous screed distributed around that time warned that “if Yale College continues to be environed with this influence [of Nathaniel Taylor], the friends of sound doctrine in this state will soon seek other seminaries for their children, and Yale will become in Connecticut what Harvard is in Massachusetts.”

In the Beginning

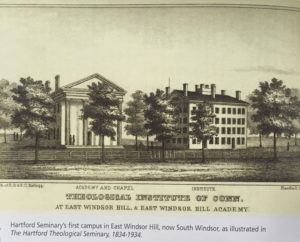

Bennet Tyler’s followers believed that it was necessary to found a seminary that represented the true Calvinist orthodoxy. They held a convention in East Windsor Hill on September 10, 1833 that led to the formation of the Pastoral Union and the Theological Institution of Connecticut, now called Hartford Seminary. Reverend Bennet Tyler was named the Seminary’s first president. The Yale Calvinists issued a public statement supporting the new seminary but objecting to the charge that Yale had become a dangerous seat of error.

The Seminary opened on October 1934 on East Windsor Hill, now called South Windsor, with two faculty and a few students. For more than ten years, it was housed in a single building containing classrooms, a chapel, and a student dormitory. Later, a separate chapel was built. (Its portico and columns stand today as the entrance to the former Ellsworth Memorial High School on Main Street, South Windsor.) As long as the Taylor-Tyler controversy raged, the Seminary was able to raise sufficient operating funds, but when the theological fire died down, the school struggled financially. Low enrollment, which some attributed to the rural location, was a continual difficulty. From the beginning some supporters argued that the Seminary should move to Hartford, which was easily accessible by steam train. In 1865, the school moved to Prospect Street; within two years 25 students were enrolled. By the late 1800s, the Seminary expanded its mission to include educating missionaries as well as ministers.

Duncan Black Macdonald and the School of Missions

The hiring of Chester David Hartranft in 1892 as a professor and librarian marked the beginning of a new era at Hartford Seminary. Hartranft enlarged the faculty, replacing retired pastors with younger men who were successful teachers and dividing the work so that each teacher could claim a specialty. The school also began grooming its students to become seminary faculty, with emphasis on scholarship and original research.

One of the most significant of Hartranft’s hires was 29-year-old Duncan Black Macdonald as instructor in the Semitic Department. A Scotsman and graduate of the University of Glasgow, Macdonald’s inclinations were those of a teacher and scholar rather than a missionary. In his Autobiographical Notes, written toward the end of his life, Macdonald noted, “I had come to Hartford determined to have a school of Arabic, although I was warned that there was no opening for Arabic in America. I found the way through Missions.”

Macdonald conceded that the education of missionaries could not be ignored, and he used it as a vehicle for advancing scholarship in Arabic studies. He wrote to a friend, “It is my greatest merit as an Orientalist that I discovered that you could smuggle Muslim studies into a theological seminary under the guise of training missionaries.” He took a long sabbatical and traveled to the Near East in 1907 and 1908. While there Macdonald became convinced that the religious missionaries were largely ignorant of Muslim faith and culture. “It is a very singular fact, but it is true, that when I began my work, there were very few missionaries who knew that the Muslims had any theological literature at all. It began and ended for them with the Koran.” Macdonald renewed his vow to advance his students’ understanding of Islam. “I made up my mind,” he said, “that if I could do anything to train missionaries to understand Islam I would put my back to it.”

His work took hold and, by 1912, what had been a special course at the Seminary in foreign missions became the interdenominational Kennedy School of Missions, with Macdonald appointed as head of the Muhammedan department. The program, with its focus not on training missionaries to convert but rather on learning to cooperate with people of other faiths, thrived. The School’s emphasis on collaboration reflected both Macdonald’s philosophy and that of William Douglas Mackenzie, the Seminary’s president.

A fellow Scotsman, scholar, teacher, and pastor, Mackenzie was a strong administrator and a long-time leader in interdenominational affairs. Under his guidance, by 1912 Hartford Seminary was robust, with more than 100 students, a distinguished faculty, and a stable financial base. That year, President Mackenzie and the board of trustees codified the Seminary’s new direction by revising the Seminary creed and eliminating an individual’s acceptance of it as a requirement for membership on the Board of Trustees and in the Pastoral Union. The committee recommending the changes noted in its report that the old creed, crafted by Bennet Tyler and the Seminary founders, “is the product of a controversial age, in which differences were emphasized; whereas we are living in a generation that is seeking to minimize the doctrinals which divide sincere Christians, and to emphasize those upon which all evangelical believers are agreed.” The report stated clearly a philosophy of tolerance and understanding that laid a new foundation for Hartford Seminary’s future: “We believe we can best honor the fathers…by re-expressing their spirit and following their method, doing for our time what th ey did for theirs through a creed which is as contemporary for us as theirs was for them.” The committee also left the door open to further changes, noting that “Neither has it been our endeavor so wisely to state Christian belief that the Seminary will never need to have another creed. Any present day confession will in the course of time cease to be contemporary; and when the right time comes, it is to be hoped that a future generation will do just what we are doing, and amend Article III once more.”

ey did for theirs through a creed which is as contemporary for us as theirs was for them.” The committee also left the door open to further changes, noting that “Neither has it been our endeavor so wisely to state Christian belief that the Seminary will never need to have another creed. Any present day confession will in the course of time cease to be contemporary; and when the right time comes, it is to be hoped that a future generation will do just what we are doing, and amend Article III once more.”

In keeping with the new creed and his own inquisitive nature, Macdonald’s scholarly interests extended beyond the study of Islam. After his retirement in 1932, he wrote two books on the Hebrew Bible, The Hebrew Literary Genius and The Hebrew Philosophical Genius. He was remarkable not only as a scholar but also as a man, a person of great warmth. Macdonald’s student and successor, Dr. Edwin Calverley, wrote in 1930:

He looked like jovial Santa Claus himself. He came into our apartment with a little snow on his shoulders, and his round cheeks were rosy and his blue eyes twinkled behind his glasses. His neatly trimmed, snowy beard was perfect for the role we imagined. And his figure, under the black suit with a white clerical collar, was really rotund. His bald head, with a fringe of tiny curls at the back, was covered with a round black hat.

Changes at the Seminary and the Macdonald Center

Born out of controversy, Hartford Seminary has undergone many, often substantial changes during its 171-year history. Since 1892, however, Arabic and Islamic studies have remained a continuous component of its work. The changing emphases and shifting constituencies of the program are reflected in the changes to the subtitle of its journal, Muslim World. When it began, in 1911, it was called Moslem World and was described as “A Quarterly Review Of Current Events, Literature And Thought Among Muhammedans And The Progress Of Christian Missions In Moslem Lands.” After two more subtitles, in 1953 it became, “A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Study and of Christian Interpretation among Muslims.” By 1970 it was called “A Journal Devoted to the Study of Islam and of Christian Muslim Relationship in Past and Present.”

Changes within the Seminary reflected broader social and political changes in the United States and the rest of the world. By the 1960s, evangelical groups dominated mission fields, and students who previously would have attended theological seminaries began to major in religious studies, a new academic discipline at many American universities. Enrollment declined precipitously at seminaries across the country.

In 1978, after a period of turmoil and reorganization from a traditional residential divinity school to an interdenominational theological center, the Seminary sold its Gothic campus to the State of Connecticut. That same year, the Seminary hired the well-regarded modern architect, Richard Meier, to design a building in keeping with its progressive vision. That building, near the intersection of Sherman and Fern streets, is the Seminary’s home today.

Hartford Seminary Today

After the cataclysmic events of September 11, 2001, the Hartford Seminary and its Macdonald Center for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations moved quickly to rededicate itself to Duncan Black Macdonald’s vision of a century before: to foster understanding of the Christian-Muslim relationship. Courses (including one on-line), community meetings, and a publication were introduced to address heightened interest and concern.

After the cataclysmic events of September 11, 2001, the Hartford Seminary and its Macdonald Center for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations moved quickly to rededicate itself to Duncan Black Macdonald’s vision of a century before: to foster understanding of the Christian-Muslim relationship. Courses (including one on-line), community meetings, and a publication were introduced to address heightened interest and concern.

Hartford Seminary’s mission to achieve interfaith dialogue and understanding continues. Named after a seeker of understanding, part of an institution born of controversy, the Macdonald Center today “seeks to foster awareness and appreciation of the Islamic religion, law and culture as a way to develop mutual respect and cooperation between Muslims and Christians.” One can imagine that in the pure light of Hartford Seminary’s interdenominational chapel, among the Christian crosses, the Muslim prayer rugs, and symbols of other faiths, the spirit of Duncan Black Macdonald abides, as his work continues.

Alexis Rankin Popik is a free-lance writer and historian working on a longer article about Hartford Seminary.