by Pamela Haag

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2016/2017

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

So far as we know, New Haven’s Oliver Winchester never displayed a gun in his home, owned one, or perhaps even shot one before he made a fortune manufacturing and sending millions of them into the world. Born in Boston in 1810, Winchester first came to New Haven in 1848, as a men’s shirt manufacturer. He is misremembered today as the inventor of the repeater rifle that bears his name. Winchester’s inventive contribution was, in fact, a patent for an improved neckband on a man’s shirt that “remedied the evil,” he promised on the patent application, of the too-tight collar.

A great deal of historical romance and legend would later attach to the Winchester rifle, including the cliché that it was the “gun that won the West.” But, for his part, Winchester viewed his product in very empirical, practical terms. In an 1868 letter to the British secretary of state for war, he described a gun as nothing more than “a machine made to throw balls.”

Winchester made his first investment in the gun business in 1855, when he became a stockholder in New Haven’s Volcanic Repeating Firearms Company. Through twists of the corporate economy, Winchester soon became the chief stockholder of the Volcanic Arms successor, the New Haven Arms Company, which became the Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1866.

That year, Winchester moved his factory from its original location in Bridgeport a few miles up the road, and laid the cornerstone for his New Haven factory. He chose farmland just north of the town proper that was approached by ordinary country roads and surrounded by cow pasture. In the coming years Winchester employees would test their rifles informally by firing out of second- and third-story windows onto these pastures, occasionally killing a stray cow in the process.

Gun manufactories at the time were disorienting, clamorous caverns redolent with machine oil, gas lamps, tobacco, and sweat. Great water wheels or coal-powered steam engines rumbled deeply; metal machines cutting metal screeched loudly. The gunsmith would not have recognized a gun in the tessellation of industrial production. The business had moved from one man making one gun, to more than 150 men each making one part of one gun. Mark Twain toured Colt’s Hartford, Connecticut factory in 1868 and found “every floor a dense wilderness of strange iron machines that stretches away into the remote distance and confusing perspective—a tangled forest of rods, bars, pulleys, wheels and all the imaginable and unimaginable forms of mechanism.” Somehow, from out of Colt’s “forest,” Twain mused, a finished, deadly pistol emerged at the other end.

This left the question of who would buy all of those guns that this miraculous industry had created. An unpublished, typewritten memoir of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company by former employees D.H. Veader and A.W. Earle , found in the company archives in Cody, Wyoming, recalls that New Haveners were “aghast at the incredible folly of anyone thinking that a production of 200 guns a day could be sold. It was freely said that Mr. Winchester had entirely lost his reason and should be confined to an insane asylum; that the plant would not run more than three or four days a year and would be shut down the remaining time,” to wither and die from lack of demand.

Winchester had always conceived of his repeater rifle as a weapon for what he called in one letter the “romance of war.” He hoped that large military contracts would answer that question of demand. But the United States Ordnance Department was not fond of either Colt’s revolver or Winchester’s repeater, at one point calling multi-firing weapons a “great evil” that used “too much ammunition.” A colonel in the department wrote to Secretary of War Simon Cameron that all the patented rifles and multi-firing arms—the arms that blazed their way into the American gun culture—“will ultimately all pass into oblivion.”

As it turns out, the Connecticut Valley, and New Haven, became the gun breadbasket to the world even before they armed the West. Hartford’s Colt’s (founded in 1855), New Haven’s Winchester, Springfield’s Smith & Wesson (another successor to the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company founded in Norwich, Connecticut in 1852), and New York’s Remington (founded in 1816) all found early markets internationally. The “American” gun business survived before and after the Civil War almost entirely on non-U.S. sales, and not the civilian, commercial market. In an 1875 advertisement Winchester could boast of his repeating rifles, “about 200,000 now in use in all parts of the world.”

Even so, Oliver Winchester’s 1879 report to his board of directors explained candidly that business had decreased. This was “attributable to the fact that all of our foreign contracts were completed. … We have [since then]depended entirely on our domestic trade.” The domestic trade was “constantly increasing,” he reassured the board—but, without the international contracts, it was still not enough.

The domestic trade, of course, meant the civilian American market, particularly the western frontier. Although it hadn’t been his first choice, Winchester would put all his energy into the commercial market just before his death. Connecticut turned its full attention to arming American civilians, especially in the West.

Mass Production Meets Mass Distribution

It is fascinating to consider that the West, as we recall it in legend, was very much a product of Connecticut’s corporate industrialism of the 1800s. Although it seems like anything but in a Western matinee film, the frontier was actually entangled with the high-tech Northeastern gun industry.

Winchester and his contemporaries perfected the mass production of guns—and their mass distribution. Via rail, they built the networks that in the most literal sense armed the West. From the Connecticut Valley factories, guns moved through the arteries of major wholesalers. The largest and most influential gun wholesaler was Schuyler, Hartley & Graham in Lower Manhattan’s financial district—seemingly a world apart from the frontier gun culture, but actually close to its heart. Gun expert and Winchester curator Herbert Houze explains that the largest percentage of arms went to Missouri and then moved west and north to the Dakota Territory and the northern plains. Dealers in Natchez and Vicksburg, Mississippi and in New Orleans were transit points for arms moving into the southern plains and Texas, respectively. It was a far cry from the days when Eliphalet Remington would ship a bundle of arms by putting a tag on the package, going to the nearby humpback bridge over the Erie Canal, lifting a board from the floor of the bridge, and dropping the gun package into the bullhead freighter as it passed underneath.

Winchester and his contemporaries perfected the mass production of guns—and their mass distribution. Via rail, they built the networks that in the most literal sense armed the West. From the Connecticut Valley factories, guns moved through the arteries of major wholesalers. The largest and most influential gun wholesaler was Schuyler, Hartley & Graham in Lower Manhattan’s financial district—seemingly a world apart from the frontier gun culture, but actually close to its heart. Gun expert and Winchester curator Herbert Houze explains that the largest percentage of arms went to Missouri and then moved west and north to the Dakota Territory and the northern plains. Dealers in Natchez and Vicksburg, Mississippi and in New Orleans were transit points for arms moving into the southern plains and Texas, respectively. It was a far cry from the days when Eliphalet Remington would ship a bundle of arms by putting a tag on the package, going to the nearby humpback bridge over the Erie Canal, lifting a board from the floor of the bridge, and dropping the gun package into the bullhead freighter as it passed underneath.

The veins of the gun market ran through retailers such as the McAusland Brothers in Montana and Omaha, Nebraska; Freund and Brothers, with depots in Salt Lake City, Laramie, and at the “terminus of the U.P. railroad”; and Simmons Hardware in St. Louis, which had its own network of traveling salesmen. Its capillaries were all the individuals who variously traded, gambled away, lost, gifted, or sold their guns. Anonymity and the suddenly vast distance between the gun maker and gun consumer in the industrial economy would still haunt the American gun culture more than a century later.

Mass Production Meets Rugged Individualism

This is how the gun made its way west in the most literal sense. But how were modern firearms promoted, and advertised? Turns out Winchester and the gun industry were also innovators in advertisement and marketing.

For the first time in the late 1870s, Oliver Winchester stressed his rifle’s nonmilitary attributes in advertisement and promotion. Rather than envisioning his customer as a troop, or army, he began to imagine his bread-and-butter customer as a civilian—one, armed individual, in private battle against beast or man. He wrote of his gun’s “moral effect,” “either upon an army or an individual”; either upon “a party of men or one single man.”

Winchester shared testimonials and stories from civilians rather than officers or military experts. For example, one testimonial reproduced in an advertisement concerned the Model 73, #289, which found its way to the Antelope Station in Cheyenne, Nebraska, where its owner proclaimed it the “BEST GUN” he’d ever used, saying, “I have often got from four to seven antelope out of a herd in less than a minute, where, with any other gun, I could not have gotten more than two shots.” Then there was the route superintendent for mail coaches at a station in Texas, whose testimonial also appeared in a pamphlet to advertise the Model 73, who killed “three or four of the enemy [Indians], and as many of their horses, with [his]Winchester rifle.” Winchester’s “prey” tended to blur like this. In one example Winchester advertised the Model 66 as the ideal weapon for “Indian, Bear or Buffalo hunting,” as if the three targets were interchangeable.

In a 1867 broadside, Winchester promoted the character capacities elicited by the repeater’s technological ones. Winchester elaborated the “coolness” of the semiautomatic shooter, and the Winchester as a boost for courage in the face of lopsided odds. Its rapid fire and reliability made the repeater “an ideal arm for…the kind of mobile warfare that was typical of Indian-white man fighting” and for those threatened with “sudden attack.” Winchester’s advertisement imagined the rifle as protection for women and children in a jittery, dangerous world, “as it is at times necessary for all men to be away from home, consequently leaving [them]to fight for themselves.”

To the extent that his rapid-firing rifle had a “moral effect,” as Winchester pondered, it was an intricate one. For the Winchester customer, a life was lived alone in both self-reliance and vulnerability. His customer achieved heroic transcendence through speed, in fight and flight, and in the always-imminent “moments of emergency.” Winchester’s world, in his coinage, was one of “single individuals, traveling through a wild country.”

The symbolic association of the Winchester rifle with this individualism is a paradox. In the 1870s, guns were in the hands of the industrialist and not the artisanal gunsmith who made a unique firearm for each customer by hand. Rather, guns were produced in a complex corporate-industrial economy, firmly grounded in New England. Each Winchester was machined to within 1/1000th of an inch of another, and with interchangeable, machine-made parts. Furthermore, these mass-produced, interchangeable rifles were mass distributed as never before. Yet, the Winchester rifle mystique was all about individualism, and autonomy. We could call it a paradox of mass-produced individualism.

Mass Marketing Gun Culture

Oliver Winchester built and cultivated the West as a market and the rifle’s mystique as a frontier gun. But was the Winchester rifle—or, for that matter, its rival to the title, the Colt’s revolver—really the “gun the won the West?”

That bromide should be taken with many grains of salt. First, the slogan “the gun that won the West” was part of a marketing campaign introduced in multiple languages by Winchester executive Edwin Pugsley in 1919.

Second, the Model 73 is most often recalled in popular culture and memory as the Winchester that “won the West,” but was barely in production by 1873—as the west was being “settled.” Precious few shipped the first years—only 18 in 1873, and 108 in 1874. And a review of the guns that Schuyler, Hartley & Graham actually sold reveals that settlers often opted for far more functional and less expensive, older gun models such as an 1842 percussion musket over the “bling” of modern repeater rifles or revolvers. Between 1873 and 1924, Winchester sold 720,610 Model 73s—but a large number after 1890, when the western frontier was declared closed.

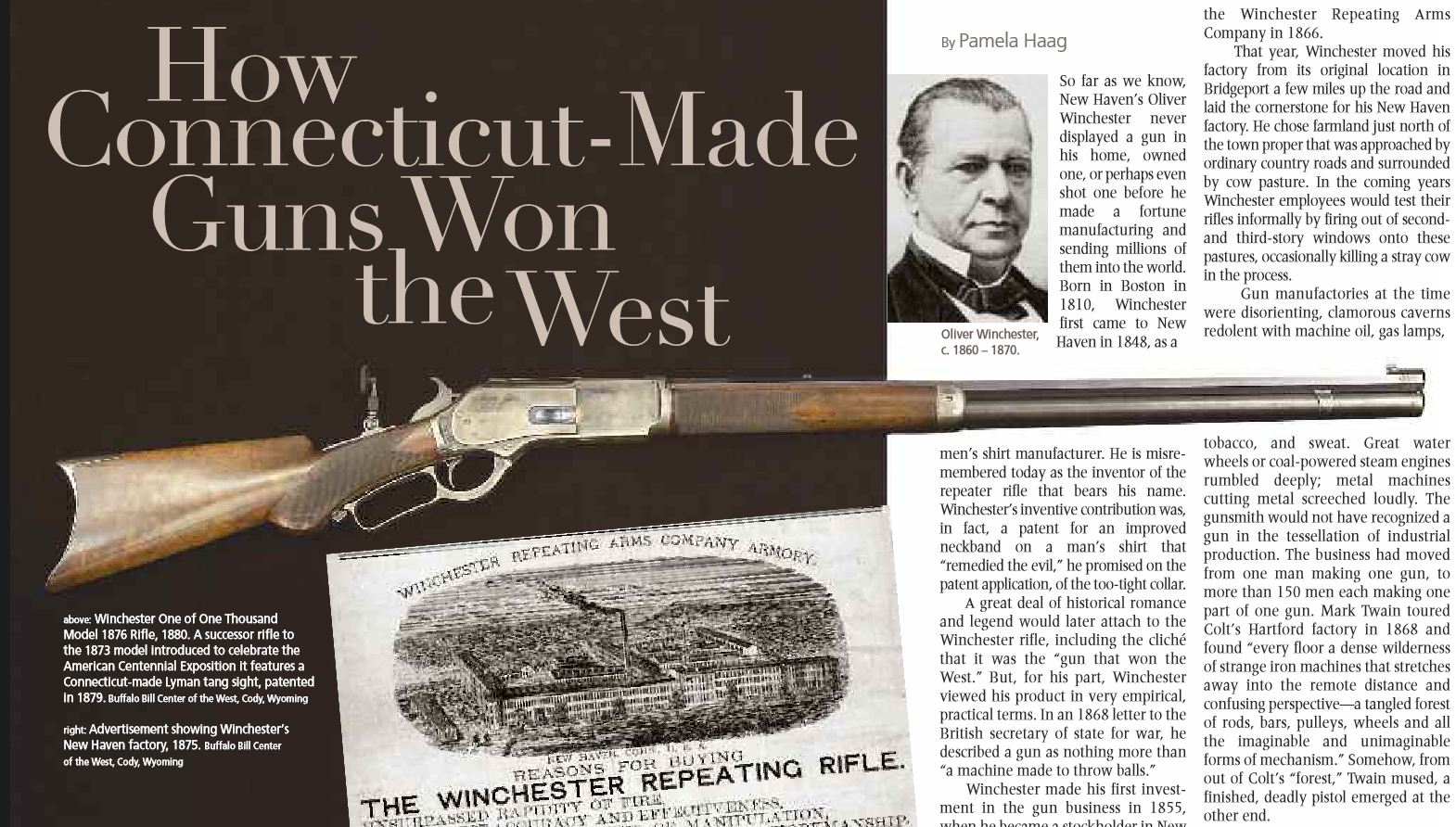

Earlier marketing also might have helped make the Model 73 a gun celebrity and enhanced the idea that it had won the West. Winchester’s “One of One Thousand” campaign in 1875 promoted the very best and the most “super accurate” of the Model 73 lot, tweaked with set-triggers and extra finishing. The company sold them at the higher price for a Model 73 of $100—roughly $2,200 today. Gun mavens today consider these the most glamorous of the Winchester family: they were used by Billy the Kid and Buffalo Bill—celebrity guns owned by celebrity gunfighters. A Winchester One of One Thousand sold in 2013 for $95,000.

In 1936, Pugsley confessed in a letter to a Winchester admirer that, “there is a great deal of mystery and hokum still clinging to the gun business.” The “atmosphere of mystery” had been even worse in the days of gunsmiths, Pugsley felt. Still, the idea of a Winchester barrel with extraordinary mechanical properties, as with the Model 73, was indeed a bit of hokum. As Pugsley put it, “a part of a billet of steel might be made into a gun part and another part of the same billet into a mowing machine, and the part which went into the gun barrel would have no more mythical properties than its brother in the mowing machine.”

“I realize that this is not good sales talk,” Pugsley conceded, “for, unquestionably, we could charge many customers $10.00 extra for a selected barrel,” as the company had in the 1870s and 1880s, he recalled, with barrels “engraved ‘one in a thousand’ and sold at an extra price.”

New Haven and the Connecticut Valley produced not only the modern firearms indelibly tied to the West (even if their presence is exaggerated)—they also produced the copy, advertisements, testimonials, dime novels, and some of the fictions and legends that tied the Winchester rifle to the frontier. These ads and stories weren’t about the gun that won the West but the “West that won the gun”—all of the fables, stories, legends, advertisement, movies, television shows, and even the plastic Wild West playsets that promoted the profile of a trigger-happy frontier, heavily armed with glamorous Colts and Winchesters, that we imagine today.

These fables began to be told in the mid-1800s with dime novels and the National Police Gazette, which wrote luridly of the West’s gunmen and always exaggerated the number of people shot by the hero—and the hero’s righteousness. But the stories of Western gunmen really exploded in the mid-1900s, during the Cold War. The sheer numbers are staggering: 35 million paperback Westerns sold annually in the 1950s; scores of “old West” magazines—also called men’s magazines—were founded in the mid-1900s; 8 of the 10 top prime-time television shows in 1959 were Westerns; more than 1,400 Western movies were released from 1935 to 1960; of the 2,400 gunslinger sagas and Westerns included in an annotated bibliography of the same, all but 241 were published in the 1900s, mostly from the 1950s.

From the Winchester factory in New Haven to the offices of dime novel Western publishers Beadle & Adams in New York City and the offices of the lurid papers such as the National Police Gazette, the story of the Wild West and its guns was in large part a product of the northeastern, corporate industrial economy. It is a rich historical irony, however, that the lore and legacy of the rugged and wild west seems very much the opposite of these northeastern worlds that produced some of its most enduring icons: The Winchester rifle, and the stories of western gunslingers.

Pamela Haag is the author, most recently, of The Gunning of America: Business and the Making of American Gun Culture (Basic Books, 2016).