(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. May/Jun/Jul 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

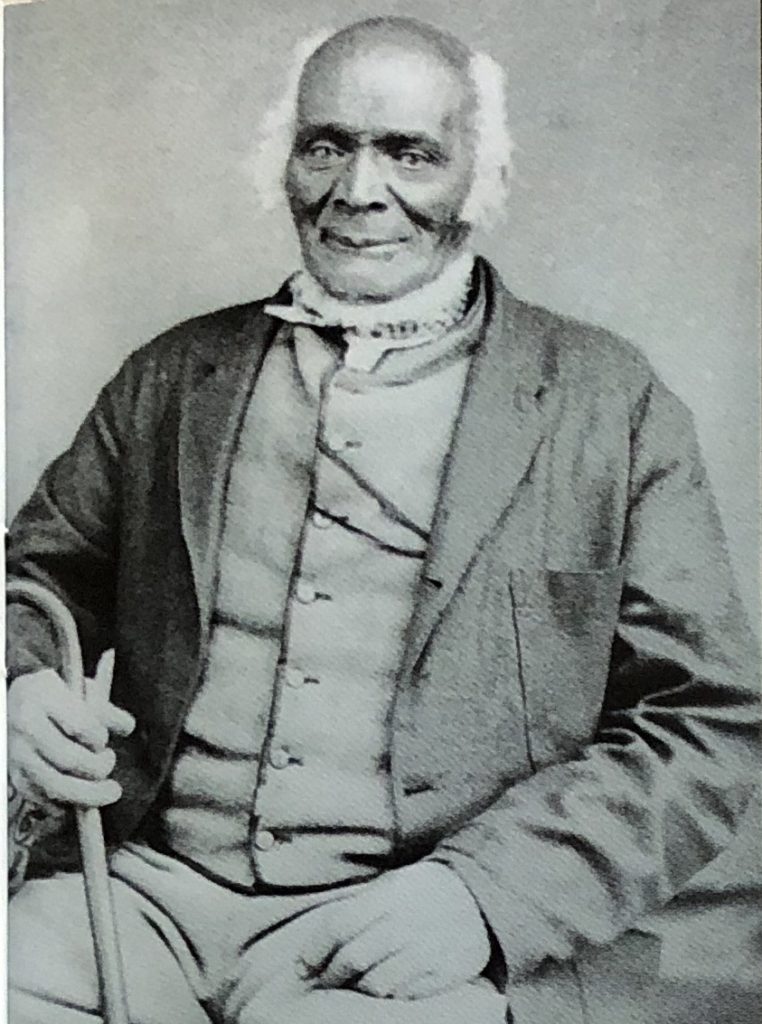

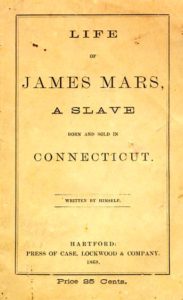

James Mars (1790–1880), a religious leader, activist, farmer, and writer who was born into slavery, analyzed the social and political challenges facing 19th-century Connecticut through the dramatic story of his family’s escape from slavery and his years of public service. His observations were documented in the Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself (Case Lockwood Company, 1868), a copy of which is held in the collection of The Amistad Center for Art & Culture. That book is excerpted here.

Mars proved a faithful witness to and a prescient commentator on issues of equality, racial privilege, faith, and citizenship. Born into slavery in Connecticut, he gained freedom in his early twenties through the gradual emancipation law enacted by the state in 1784. His defiance in supporting independent black churches, facilitating the escape and legal defense of an enslaved southerner living in Connecticut, advancing petitions to the legislature, and writing an autobiography defined Mars as an engaged critic on the issues of his day—many of which are now critical issues for ours. These issues—inequality in the experience of black and white youth, the fight for full citizenship, and the struggle to retain one’s humanity while fighting or surviving injustice—are reflected in the excerpts reprinted here.

Although there are other Connecticut-based slave narratives (Venture Smith, James Pennington), the drama and compassion of Mars’s story, his skillful portrayal, and his good luck in being a portrait subject combined to make him a recognizable presence and his life an American parable. He survived the horrors of slavery and went on to live a productive life influenced by religious teachings. Mars fought against slavery but was able to forgive those who held slaves. For Mars that meant reconciling with Mr. Munger, who kept him until he was an adult, but with whom he later became and remained friends. Of the varied labors Mars performed, both as a slave and as a free man, it is the totality of his life’s work as recounted in his autobiography that draws us back for repeated readings, references, and interpretations.

I soon found that I was to live or stay with the man until I was twenty-five. I found that white boys who were bound out, were bound until they were twenty-one. I thought that rather strange, for those boys told me they were to have one hundred dollars when their time was out. They would say to me sometimes, “You have to work four years longer than we do, and get nothing when you have done, and we get one hundred dollars, a Bible, and two suits of clothes.” This I thought of . . . I had now got to be in my sixteenth year, when a little affair happened, which, though trivial in itself, yet was of consequence to me. It was in the season of the haying, and we were going to the hayfield after a load of hay. Mr. Munger and I were in the cart, he sitting on one side and I on the other. He took the fork in both of his hands, and said to me very pleasantly, “Don’t you wish you were stout enough to pull this away from me?” I looked at him, and said, “I guess I can;” but I did not think so. He held it towards me with both his hands hold of the stale. I looked at him and then at the fork, hardly daring to take hold of it, and wondering what he meant, for this was altogether new. He said, “Just now see if you can do it.” I took hold of it rather reluctantly, but I shut my hands right. I did as Samson did in the temple; I bowed with all my might and he came to me very suddenly. The first thought that was in my mind was, my back is safe now. . . .

. . . Although born and raised in Connecticut, yes, and lived in Connecticut more than three-fourths of my life it has been my privilege to vote at five Presidential elections. Twice it was my privilege and pleasure to help elect the lamented and murdered Lincoln, and if my life is spared I intend to be where I can show that I have the principles of a man, and act like a man, and vote like a man, but not in my native State; I cannot do it there, I must remove to the old Bay State for the right to be a man. Connecticut, I love thy name, but not thy restrictions. I think the time is not far distant when the colored man will have his rights in Connecticut.[i]

[i] Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself (Hartford: Case Lockwood Company, 1868). The complete text of Life of James Mars, a Slave Born and Sold in Connecticut. Written by Himself can be accessed on line at http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/mars/menu.html. Also, Mars’s grave in Norfolk’s Center Cemetery is a site on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

Explore!

Read More about Slavery in Connecticut

Read more about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Read more about other Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.

Read more from the May/Jun/Jul 2004 issue.