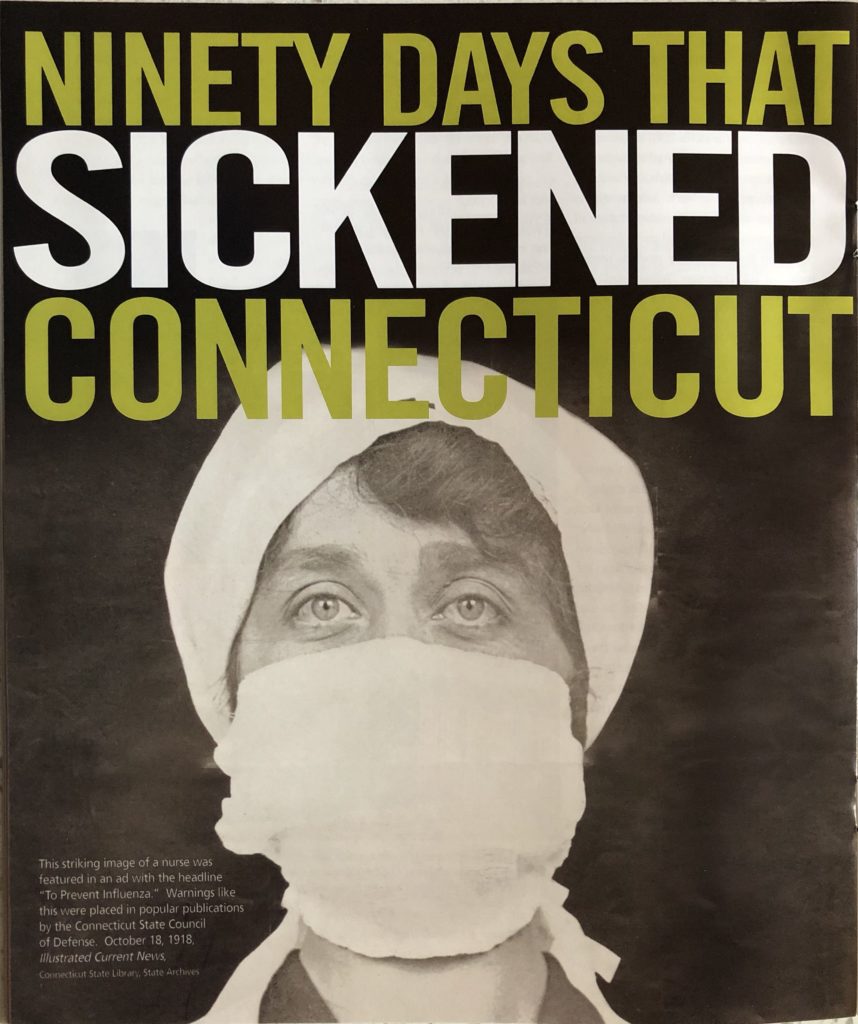

A nurse featured in influenza prevention ads by the Connecticut State Council of Defense, Illustrated Current News, October 18, 1918. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

By Ralph D. Arcari, Ph.D.

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Almost 90 years ago, in September 1918, an influenza pandemic that was spreading all over the world arrived in Connecticut. Following a deceptively less dramatic outbreak in the preceding spring, the pandemic raged across the state for 90 days. The virulent disease, for which there was neither a cure nor a preventative vaccine, claimed the lives of 8,500 Connecticut residents; it killed more than half a million people in the U.S. and as many as 100 million around the globe. Statistically, the 1918 influenza’s death rate ranks with that of the two major bubonic plagues of late antiquity and the Middle Ages—the plague of Justinian (550 A.D.) and the Black Death (1348-1351).

Yet the 1918 pandemic has, until recently, been accorded little public or professional recognition. In the prologue to her 1999 book Flu: the Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It, New York Times science writer Gina Kolata noted “If anyone should have known about the 1918 flu, it was I. I was a microbiology major in college and even took a course in virology. But the 1918 flu was never mentioned. I also took history courses in college, with one of my favorites being a class that covered important events of the 20th century. But although World War I was a major part of the course, the 1918 flu was not discussed.”

For Connecticut, the 1918 influenza epidemic was a public health disaster. Connecticut was particularly vulnerable and ranked high in number of deaths compared to other states: as World War I raged, the state’s international ports, particularly New London with its Navy base, served as transit point for military personnel disembarking for or returning from Europe—and for whatever communicable disease they might be carrying. Further, the state’s industrialized, dense, urban areas, where European immigrants had settled in the early years of the 20th century, had individuals living in close proximity, making them exceedingly susceptible to the air-borne contagion by which influenza is spread. Influenza advanced in Connecticut in a somewhat counter-clockwise pattern, entering through New London County, heading north to Windham, west to Tolland and then south and west to New Haven, Hartford, Fairfield, and Litchfield counties.

As the British medical journal The Lancet reported in its January 4, 1919 issue, the disease came on suddenly with chills, fever, and pain in the legs, head, and eyes, often accompanied by severe backache. When a person’s ears, lips, and face became ashen, the illness was progressing toward mortality. A heliotropic or purple color in the patient’s face, a sign of cyanosis resulting from lack of oxygen, indicated that death was imminent. Coughs varied in their intensity and were often accompanied by copious amounts of sputum. Blood in the expectorant was a certain sign of bronchopneumonia. Temperatures reached 103 to 104 degrees. Despite the grisly symptoms, “The great majority of cases of influenza, of course, recover,” the article reported. In terms of deaths per 1,000, Connecticut’s rate was 6.2. Among 24 reporting states, the highest death rate was in Pennsylvania with 7.3; the lowest Michigan at 2.9. Thus, better than 90 percent of those who became ill recovered.

Perhaps most gripping is the fact that, unlike today’s influenzas, which tend to strike hardest at the very young and the very old, the 1918 strain claimed more people—some 5,000—at the prime of life, between the ages of 20 and 39. It appears that young adults, spending their time in tenements, factories, and the wartime military were hardest hit. Those in military quarters, for example, often slept in bunk beds or on cots in shared facilities.

From Camp Greenleaf, Georgia, Irwin V. Johnson, in a letter in the Connecticut Historical Society’s collection dated October 17, 1918 wrote to his niece Abbie C. Barber in Winsted, their hometown, “The flu certainly must be raising the deuse [sic]up there, as well as down here. The average death rate daily in this camp is about forty. I think there are about (30,000) men in this camp today, where a month ago there was [sic]about (80,000). The flu has stopped the draft work so there has [sic]not been any men shipped down here lately.”

The largest number of influenza-related deaths in Connecticut at the height of the epidemic occurred in the state’s largest cities: Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport, and Waterbury. In each of these urban centers the number of dead approached 1,000. However, the actual death rate was much higher—11.7 per thousand compared to 6.8 per thousand—in the smaller towns of Derby, Seymour, and Windham, mill towns with factory workers existing in close proximity to one another.

Deadly, but not Always Newsworthy

Yet it would appear that not everybody at the time was paying much attention. The rampant disease commanded few headlines, for instance, in The Hartford Courant, whose editors presumably were preoccupied by the ongoing war. Perhaps, too, in a time when most serious diseases had no cure, the general public found the death toll—so shocking to today’s sensibilities—less than newsworthy.

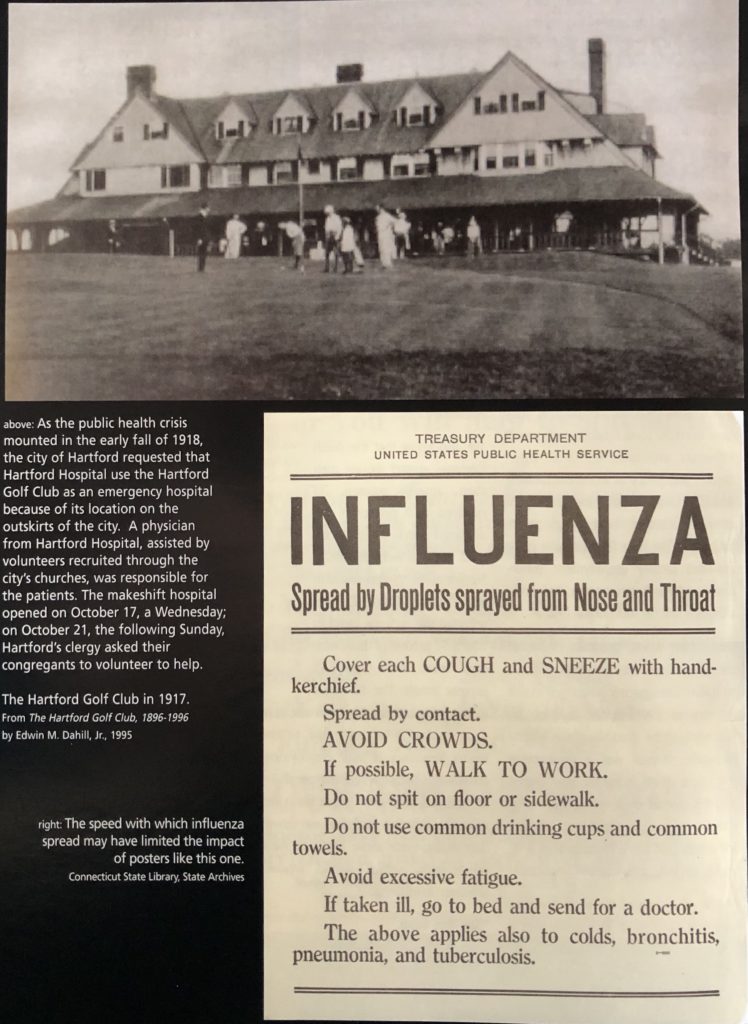

top: The Hartford Golf Club, 1917. The clubhouse was used as an emergency hospital because of its location on the outskirts of the city. From “The Hartford Golf Club, 1896 – 1996.” Bottom: Broadside, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

John Barry, in his book The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (Viking, 2004), found that government censorship did suppress stories on the pandemic in an effort to prevent wartime morale from slipping.

The federal government was giving no guidance that a reasoning person could credit. Few local governments did better. They left a vacuum. Fear filled it. The government’s very efforts to preserve “morale” fostered the fear, for since the war began, morale . . . had taken precedence in every public utterance. . . Newspapers reported on the disease with the same mixture of truth and half-truth. . . And no national official ever publicly acknowledged the danger of influenza.

Although influenza may not have headlined popular magazines and newspapers in 1918, the pandemic was immediately the subject of public health reports and analyses in professional journals just afterward. In the April 1919 issue of the Connecticut Health Bulletin, the state health department published an article on the impact of the pandemic on the state. Morbidity (cases of illness) and mortality tables were provided, and the article concluded that the “epidemic of influenza was a blasting thing, many times more devastating than the war. It was proportionately as harmful to the population of Connecticut as was any year of the war to any of the belligerents engaged.”

Who Was Hardest Hit?

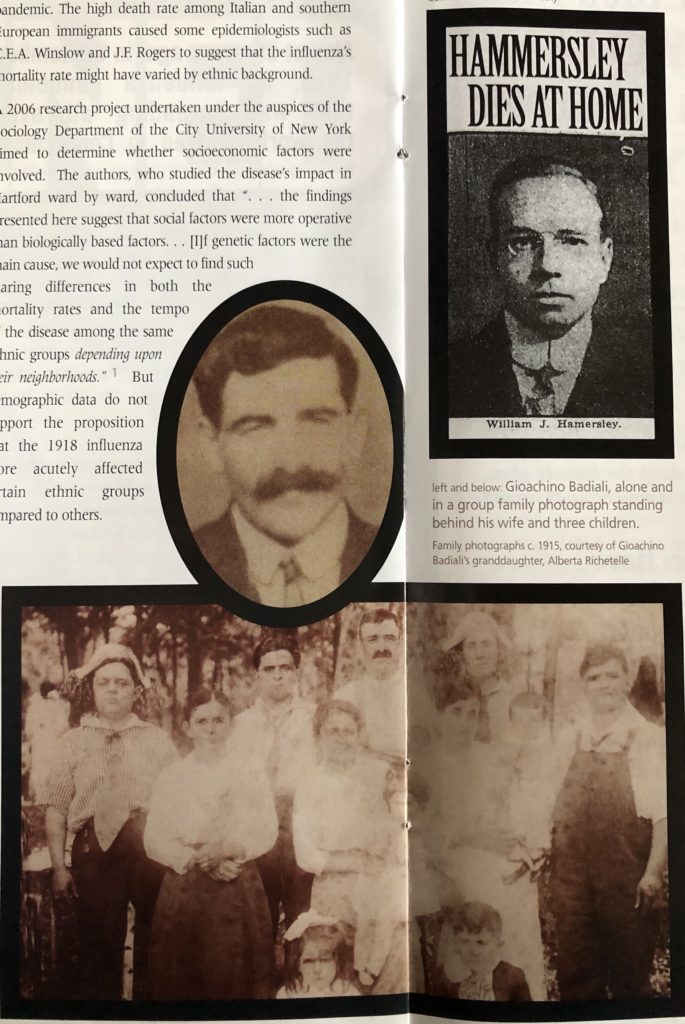

Many researchers have speculated as to the sociological, genetic, and economic underpinnings of this lethal and fast-moving pandemic. The high death rate among Italian and southern European immigrants caused some epidemiologists such as C.E.A. Winslow and J.F. Rogers to suggest that the influenza’s mortality rate might have varied by ethnic background.

A 2006 research project undertaken under the auspices of the Sociology Department of the City University of New York aimed to determine whether socioeconomic factors were involved. The authors, who studied the disease’s impact in Hartford ward by ward, concluded that “. . . the findings presented here suggest that social factors were more operative than biologically based factors. . . [I]f genetic factors were the main cause, we would not expect to find such glaring differences in both the mortality rates and the tempo of the disease among the same ethnic groups depending upon their neighborhoods.” (1) But demographic data do not support the proposition that the 1918 influenza more acutely affected certain ethnic groups compared to others.

While immigrants of Italian stock are heavily represented among the victims, it is noteworthy that their mortality rate was no greater than that of immigrants of Russian/Lithuanian stock. This finding counters the notion that the “excessive” mortality rate of Italians was due to a particular biological susceptibility to the disease. [Italians were 17.5 percent of Hartford’s population and 22.5 percent of the influenza victims. These figures for Russians/Lithuanians are 21.9 and 28.6, respectively](2)

It now appears that the following factors, often characteristic of newly arrived immigrants such as the Italians, may have been the most reliable predictors of influenza outcomes in 1918: high-density occupancy in tenement housing including common toilet facilities shared among apartment houses; single males living together to reduce housing costs; crowded factory employment conditions; and workers reporting for work, although sick, to prevent job loss.

One victim whose situation embodied these conditions was Gioachino Badiali, an Italian immigrant who arrived in this country in 1909 at the age of 26. Mr. Badiali was a stonemason from Springfield living in New Haven with his mother while working at a construction site in Rhode Island. Mr. Badiali left a wife and three children ages 9, 8, and 3. Mrs. Badiali subsequently remarried.

top: newspaper clipping announcing the death of prominent Hartford lawyer William J. Hammersley, October 12, 1918. Mary Morris Scrapbooks Collection, Connecticut Historical Society. Middle and bottom: Gioachino Badiali and family, c. 1915. Courtesy of Gioachino Badiali’s granddaughter, Alberta Richetelle

At the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum, William J. Hamersley was a prominent 31-year-old Hartford lawyer who died from influenza on October 12, 1918. Papers in the Mary P. Morris Scrapbook Collection at the Connecticut Historical Society show that Hamersley became ill at Camp Devens, Ayers, Massachusetts, where he had gone as recently as September 11, 1918. In civilian life Hamersley had been a state representative and assistant corporation counsel for the city of Hartford. He had also been associated with the American Red Cross and the city’s juvenile commission. Hamersley was an alumnus of Trinity College and Harvard Law School. He left his wife of two years, Emily Brace Collins, and an infant daughter, Jane. Emily Hamersley remarried in 1922.

We also know that the death rate was greater among men than among women In Hartford, 56.8 percent of the deceased were male while 43.2 percent were female. (3) Similar numbers were found in Waterbury. (4) These findings reflected the national trend in which 57 percent of those who died were male and 43 percent female. The difference in the mortality rate (approximately 10 percent) has been attributed to the higher frequency of male employment outside the home, where the possibility of contact with the influenza virus would be higher. A study has also shown that males were more likely to have tuberculosis, which would weaken resistance to influenza. (5)

“She Was Gone”

Those who can personally remember the 1918 influenza are few now. However, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the epidemic, the December 19, 1993 Hartford Courant ran a front-page story with the headline “Horrors of the state flu epidemic still vivid after 75 years.” Among the memories recorded in the article was that of Joseph Camp of Hartford, who was eight years old in 1918. He returned home after hospitalization for influenza to find his mother wasn’t there. “[F]inally my sister told me. She was gone.”

Charles Begley was a nine-year-old Hartford grammar school student in the fall of 1918. He recalled going to St. Joseph’s elementary school on a November Monday only to find the school was closed. “The head sister came to the window and said ‘Sorry, you have to go home; the sisters are sick.’” The school remained closed for three weeks. At the time of the epidemic, The Hartford Courant reported that not only schools but soda fountains, theaters, and other public places were being closed to avoid infection.

Recent interviews of residents at Avery Heights in Hartford yielded several personal accounts. One resident, who requested her name not be used, was four years old and living in rural eastern Connecticut when the pandemic struck. Her mother was pregnant with her brother. Her father, a farmer and local sheriff in his early thirties, died from influenza after a four-day illness.

The epidemic affected some survivors for the rest of their lives. Betty Glickman’s uncle, Joseph Frisch, was in a Maryland army camp as a soldier when influenza broke out in 1918. Joseph, only 17, was assigned to work on a burial detail, and this responsibility appears to have affected his mental health. When he returned home he was reclusive, would not go outside during the day, and took a night position in Hartford with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railway. He never married but avidly followed sports and could recall team statistics long after events had passed.

The 1918 influenza, as these personal stories relate, cut a swath of devastation across all segments of society. Because males ages 20 to 40 were significantly affected, in its wake the influenza left many young widows and fatherless children.

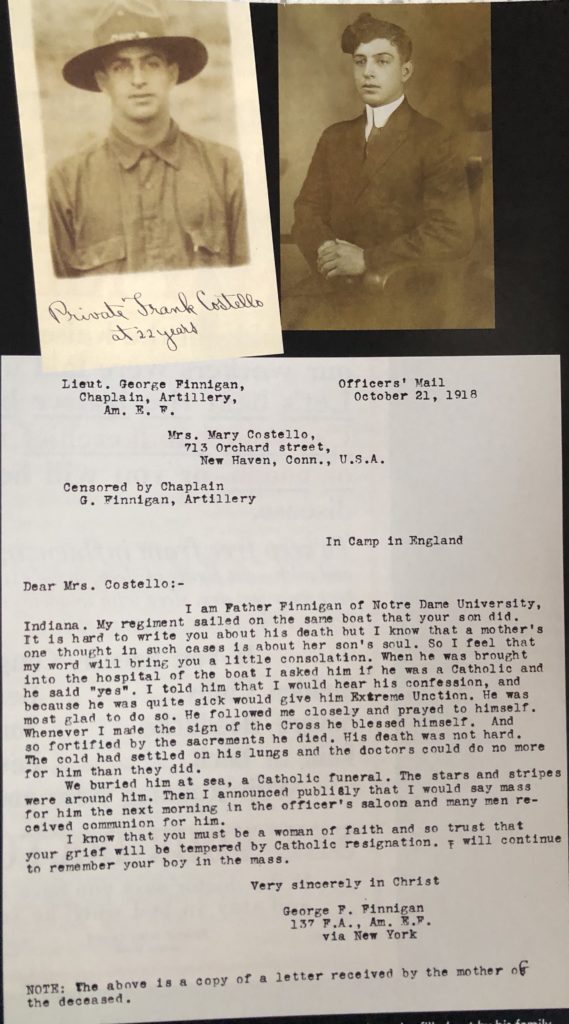

top: Frank Costello, Jr. of New Haven, died at sea from influenza, October 1918. Bottom: Letter of condolence to his mother from Father George Finnigan, October 1918. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Could it Happen Again?

Today’s heightened interest in this influenza episode stems of course from public health officials’ efforts to ascertain how a contemporary influenza pandemic—most notably the recent outbreak of the Avian flu—might spread and what measures can be put in place—measures that were available or not in 1918. In medical journals alone, the average number of articles on the subject has jumped from just 4 per year between 1950 and 1999 to 33 per year since 2000.

The 1918 influenza pandemic killed more Americans than any one of the major wars that the United States has been engaged in. Moreover, “It was a plague so deadly that if a similar virus were to strike today, it would kill more people in a single year than heart disease, cancers, strokes, chronic pulmonary disease, AIDS, and Alzheimer’s disease combined,” asserts Kolata.

Could the 1918 strain of influenza reappear and cause the same level of human destruction now that occurred then? This perennial question was posed to Matthew L. Carter, M.D., an epidemiologist with the State of Connecticut’s Department of Health Services, State of Connecticut. Dr. Carter characterized the 1918 influenza pandemic as “a perfect storm” in which conditions came together simultaneously to create an international disaster: a world war, an influenza strain mutated through several waves for virulence, ineffective vaccines, no antibiotics, mass immigration, inferior urban living conditions, no communicable disease warning system, and minimal or no employee health benefits or rights.

Most experts believe that an exact replication of those conditions now is not likely. However, other conditions have entered the scene. The speed of travel via international commercial aircraft services, inter- and intra-country high-speed highways, terrorist organizations, and regional wars are contemporary factors that could exacerbate the spread of an influenza epidemic. The question, in Connecticut and throughout the world, is whether these and other factors could combine to form the next perfect storm.

Ralph Arcari, Ph.D. is assistant professor in the department of Community Medicine at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, where he teaches the history of medicine course.

1. Peter Tuckel; Sharon Sassler; Richard Maisel; Andrew Leykam. “The diffusion of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 in Hartford, Connecticut.” Social Science History, Summer 2006, vol. 30, p. 191.

2. Ibid., p. 176, 177.

3. Ibid., p. 177

4. G. Wallach. “The Waterbury influenza epidemic of 1918/1919.” Connecticut Medicine, June 1977, vol. 41, p. 349.

5. Andrew Noymer, Michel Garenne. “The 1918 Influenza Epidemic’s Effects on Sex Differentials in Mortality in the United States.” Population and Development Review, September 2000, Vol. 26, 2000), pp. 565-581.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s medical history in Spring 2007 and Feb/Mar/Apr 2004 and on our Health & Medicine TOPICS page