By Joseph Newman

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Three hundred and seventy years ago, the English settlers at Saybrook Fort on the Connecticut River’s west bank regarded the land that is now Old Lyme as hostile. The rolling hills, rocky outcroppings, and thick copses of the east bank afforded Pequot warriors ample cover from which to launch harrying attacks on the colonists. Deteriorating relations between the colonists and the neighboring Native American tribes stalled further settlement, but after the Pequot War of 1636-1638, the Saybrook Colony expanded, and the town of Lyme was incorporated in 1665.

The colonists soon spread north along the river. Rich farmland and access to the water encouraged agriculture and maritime trade. Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, wealthy ship captains built mansions along Lyme Street. Prominent families ensconced themselves in the landscape. At their economic zenith, Lyme and Old Lyme split into separate towns in 1855. The rise of steam power soon after, however, rendered the local packet ships–and their captains–obsolete. The local economy foundered, and Lyme and Old Lyme grew old and quiet.

Unbeknownst to the staid residents of the town, the man who would introduce a new industry of sorts into their economy had already begun the artistic quest that would eventually bring him to Old Lyme. In 1878, Henry Ward Ranger, a young watercolorist with a rising reputation, relocated from Syracuse, New York to Manhattan to further study art. Being in the city gave him the chance to view the Barbizon landscapes of Millet and Corot,[i] whose sometimes melancholy, sometimes joyous moods inspired him. The son of a photographer who’d traveled the world to capture the Transit of Venus,[ii] Ranger was a traveler, too. He traveled to Paris. He traveled to Holland, to seek out the “linear successors” of the Barbizon movement.[iii] In the early 1890s, Ranger returned to America to experiment painting his native country. He sought unsullied places near New York that offered the same diversity of subject that he had found overseas. In 1899, he discovered Old Lyme.

He arrived at a fortuitous time for a town whose history of receding fortunes could be read across the weathered façade of the old Griswold house at the north end of Lyme Street. Inside the once-stately Late Georgian mansion lived Miss Florence Griswold, 49 years old, unmarried, and alone. A failed attempt to establish a finishing school for young girls had compelled her to open a boarding house.[iv] (For more information about Griswold’s boarding house, see Liz Farrow’s “The Spirit of Miss Florence Restored,” HRJ Winter 2005/2006.)

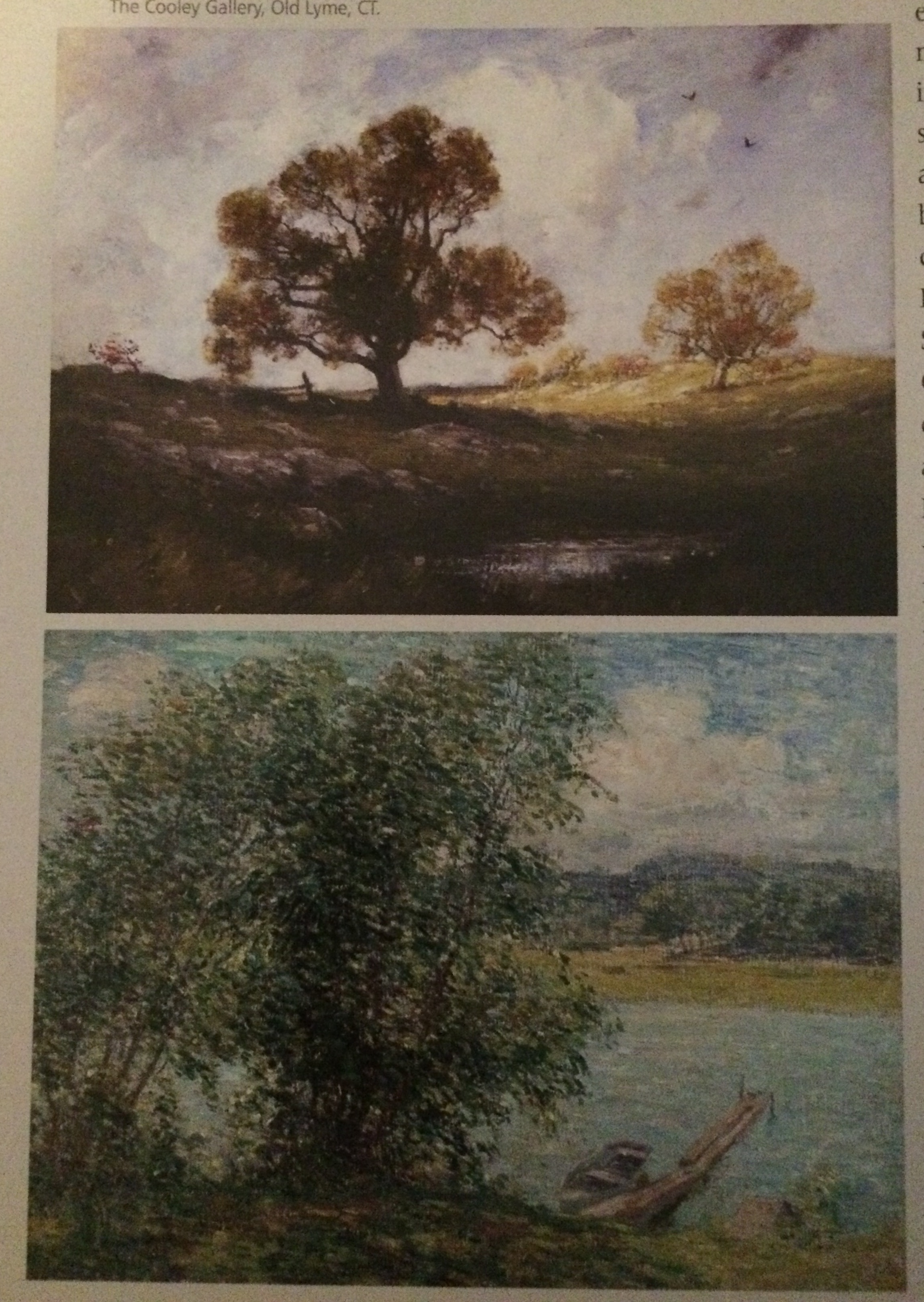

Top: Guy Wiggins, “Autumn Pasture, Lyme.” Bottom: William S. Robinson, “The Landing,” courtesy of The Cooley Gallery

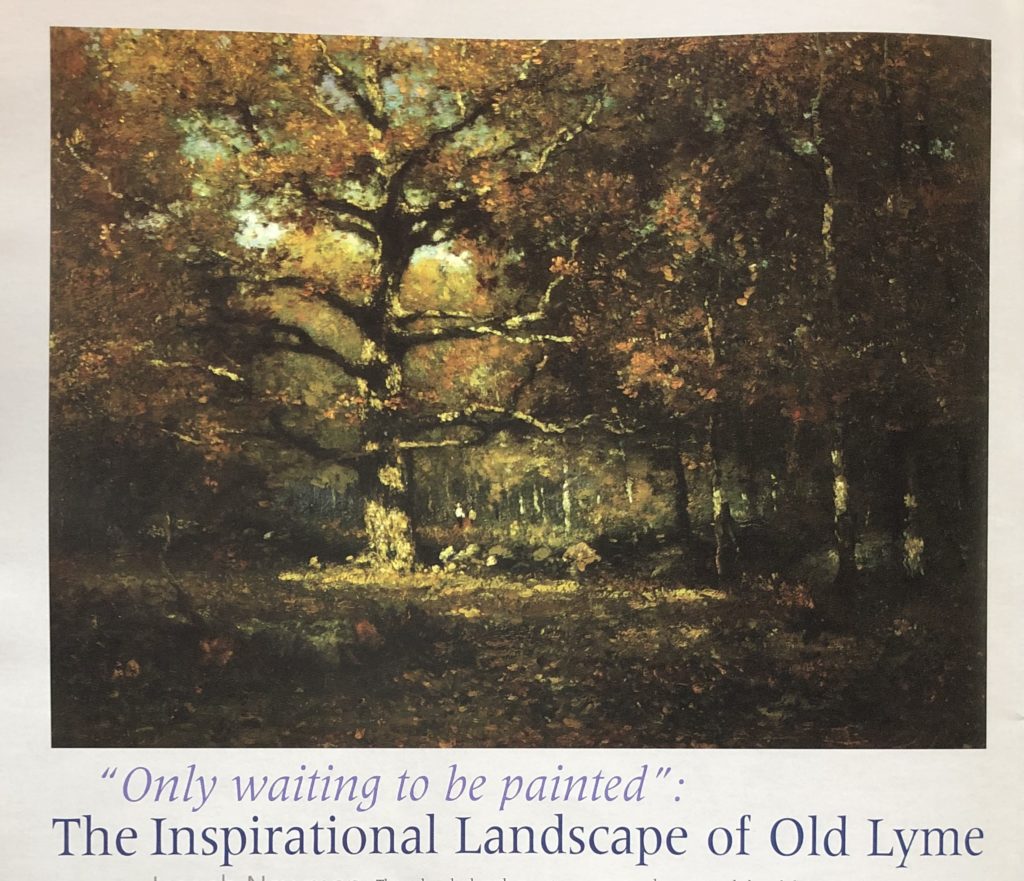

Ranger fell in love with the landscape. Years later he would famously write to a friend, “It looks like Barbizon, the land of Millet. See the gnarled oaks, the low rolling country. This land has been farmed and cultivated by men, and then allowed to revert back into the arms of Mother Nature. It is only waiting to be painted.”[v] That first summer, Ranger produced Connecticut Woods, a forest interior view showing a hoary oak illuminated by crepuscular blue light filtering between the leaves. With its predominantly brownish-orange palette and judicious use of atmosphere, it is a landmark example of the Barbizon style in America, and one in which the rocks, trees, earth, and light of Old Lyme are celebrated to the measure of their ancient history.

Ranger returned to the area the following summer, bringing scores of like-minded artists in his train. Among them was Allen Butler Talcott, a Hartford native whose style of landscape painting followed Ranger’s away from strict Barbizon-school pictures toward what gradually became known as American tonalism. The preeminent art critic William H. Gerdts describes tonalist artists as “not concerned with transcription but with poetic evocation, suggesting in pure landscape the feelings of reverie and nostalgia, psychological states often associated with and induced by evening and night particularly.”[vi] A strong example of this “poetic evocation” is Talcott’s Clearing Skies Over Black Hall, the subject of which is a primitive bridge over the Black Hall River. The Black Hall is one thread of a tangled skein of rivers crisscrossing the town. Talcott renders the shores a uniform russet-green similar to the style of Ranger’s Connecticut Woods, but the dramatic pinkish light shining down–so familiar to the region as to be called “Lyme Light”–lends an oneiric quality to the scene.

Thanks to Ranger’s boisterous and exuberant personality, “Miss Florence” (a sobriquet preferred by her boarders) soon found her house filled with artists of the first rank. As word spread of the artists’ colony, pretenders and acolytes crowded Lyme Street. Even the local cows found fresh work as unwitting models. The forgotten town stirred to life.

Ranger ruled supreme until a new lion lumbered into his den of painters. Childe Hassam had already begun experimenting with Impressionist techniques by the time he came to call on Griswold. As with Ranger, Hassam’s charisma, grounded in his passion for plein air painting, influenced the style of the artists gathered at the Griswold mansion. With the influx of new artists such as Willard Metcalf and Walter Griffin, and bolstered by the conversion of Allen Butler Talcott, William S. Robinson, Bruce Crane, and others, the colony shifted toward a new brand of Impressionism, one that would establish Old Lyme’s role in the history of American art.[vii]

Evidence of this shift is demonstrated in Guy Wiggin’s Autumn Pasture, Lyme. Elements of the Barbizon School can be found in the composition of the large tree that occupies the center of the canvas, and the ground below the tree is created from a relatively uniform range of greens. But the amplified bright blues in the sky and in the foreground pool distance the work from its Barbizon and tonalist antecedents. Most significantly, the sweeping angle of the grass in the meadow, which is matched by the motion of the clouds overhead, suggests the rush of wind. These qualities, along with the looseness of the rock forms and additional flora, confirm the work’s Impressionistic character.

Displaced by Hassam, Ranger moved on to Noank, 22 miles east on the Connecticut shoreline in 1904. Hassam himself lived a peripatetic life, and his exploding popularity soon carried him beyond Old Lyme, to Cos Cob, to the Northwest coast, to Europe, and eventually to Long Island. But the second tier of Old Lyme painters—Will Howe Foote, Frank Bicknell, Louis Cohen, William S. Robinson, Allen Butler Talcott, Matilda Browne, and others—remained. They closed ranks and formed the Lyme Art Association in 1914. Its gallery, designed by Charles A. Platt, opened in 1921. The colony and association thrived. Today, nearly a century later, Lyme Street is still crowded, and the local cows still pose for pictures.

Landing at the stoplight off Exit 70 from I-95 northbound, it’s difficult to guess that Griswold’s boarding house, now a world-class museum, is less than two miles away. A quick jog left, then a right past a bustling strip mall, brings you to the head of Lyme Street. Turn left again, and just past the Lyme Art Association you’ll spy the mansion where the art colony began. Open to the public since 1947, the Florence Griswold Museum recently completed a 14-month historic renovation. Inside and out, the house appears now as it did during the heyday of the Lyme Art Colony.

Landing at the stoplight off Exit 70 from I-95 northbound, it’s difficult to guess that Griswold’s boarding house, now a world-class museum, is less than two miles away. A quick jog left, then a right past a bustling strip mall, brings you to the head of Lyme Street. Turn left again, and just past the Lyme Art Association you’ll spy the mansion where the art colony began. Open to the public since 1947, the Florence Griswold Museum recently completed a 14-month historic renovation. Inside and out, the house appears now as it did during the heyday of the Lyme Art Colony.

It’s been a busy decade. In 1996, the museum established a master plan to transform itself from a beloved local attraction into a national cultural landmark. In 1998, an archeological excavation uncovered the original site of Hassam’s studio. A year later, the museum opened the Hartman Education Center, which hosts educational workshops, summer camps, and hands-on events. In 2001 and 2002, the museum acquired by donation the unparalleled collection of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company and opened the ultra-modern Robert and Nancy Krieble Gallery to exhibit it.

Behind the Krieble Gallery, the Lieutenant River winds north into the rural interior toward Roger’s Lake. Guests are invited to take canvas, brushes, and paints down to the bank to experience for themselves the plein air tradition of Hassam and his followers. Museum director Jeff Anderson is enthusiastic about the insight the museum provides into the lives of the artists. “Visitors can walk in the actual landscapes that inspired the artists, view paintings of those landscapes, and experience first-hand the communal boardinghouse where they lived and worked,” he says. “To this day, painters of all ages and skill levels come to capture on canvas the delightful views, keeping alive a tradition that started here over 100 years ago.”

If the Florence Griswold Museum is the historic cornerstone of the art colony in Old Lyme, then the Lyme Art Association next door provides its modern-day framework. The gallery Platt designed for the artists still stands, its shingles beaten by the New England weather to a chocolate brown. Natural light pours through four enormous skylights in the roof. Bob Potter, the Lyme Art Association’s executive director, says, “The association is part of this landscape of art in Old Lyme. This landscape in many ways hasn’t changed in a hundred years. If you go in the back country, you’re seeing the same rock walks, the rolling hills, the rivers that the original Impressionists saw. And it continues to attract artists, not just locally, but nationally as well.”

One of those artists attracted to Old Lyme is Jerry Weiss. A native of south Florida and a past resident of New York for 15 years, he relocated here because of the land’s diversity. Weiss describes his affinity for the region. “You have the ocean, the confluence of many rivers, farmland, marshland, low rolling hills, and forest…. Growing up in Florida, I really had an idealized vision of New England. It connects to snowfall and evergreens. It’s magical and otherworldly.” Around town, Weiss is easily spotted by his trademark Pendleton crusher hat, an accessory that seems appropriate for an artist who routinely traipses into the wild, away from humankind, to paint. Some artists have no compunction pulling off onto the shoulder and painting beside their cars, but it’s an activity that can become less about painting and more about serving as some sort of roadside attraction. For Weiss, art is about a relationship with nature. “I’d rather find a place off-road where no one is going to see me,” he says, “and do the Thoreau thing.” Hassam would have approved.

The Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts, where Weiss teaches part-time, stands on a newly expanded campus just half a mile down Lyme Street from the Lyme Art Association. In many ways, the college is the opus of Elizabeth Gordon Chandler, a long-time member of the Lyme Art Association, town resident, and world-renowned sculptor who, in the early 1970s, became concerned that the traditional, academic methods of fine-art instruction were passing into the dustbin of history.

Chandler cast the bronze reliefs found on either side of the nave at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York; she also wrought the bust of Adlai Stevenson at Princeton University. Chandler, now 92 years old, maintains a studio attached to a meandering colonial-style house she designed herself. The pulleys she used to hoist the reliefs destined for St. Patrick’s still hang from the ceiling. Chandler recalls the school’s founding: “Young people were coming into the association gallery asking, ‘Where can I learn art like this?’ After World War II, there was nothing for representational art. We were telling students to sit down and express yourself, the idea being anything else would suppress their creativity. Young students wanted to learn. I said to myself, if something isn’t done to teach the way they used to teach in the academies of old, there won’t be anyone left around to teach it.”

Her election to the presidency of the Lyme Art Association in 1974 gave Chandler the leverage she needed. After some initial difficulties, the school opened in 1976 in the basement of the Platt gallery. Over the next decade, the school quickly outgrew its facilities until it acquired the Sill House on Lyme Street. In 2003, a new academic center was added, and today the college is a respected degree-granting institution offering a BFA in Fine Arts along with certificates in sculpture and painting. Nearly half the student body comes to the college from out of state.

“I’ll tell you one thing. It’s not the light.” That’s school president Fred Osborne’s pragmatic answer to the question of what draws prospective freshmen to Old Lyme. “Students choose this school because of its traditional approach. The college and the Pennsylvania Academy are the only two institutions teaching in the Western tradition of drawing and the study of color. We’re interested in the physical, technical, and conceptual skills that have been the hallmarks of that tradition.” It’s a methodical approach and, judging from the increasing roll of professional artists counted among its alumni—names like Ralf Feyl, Peggy Root, and Tim Lawson—one that seems to be working.

In a town saturated with art history, the Cooley Gallery, a half mile further down Lyme Street from the college, is an engine of the present, a commercial retail gallery that offers works of 19th- and early 20th-century representational art to the buying public. The gallery is housed in a late Federal-style converted carriage house that is painted the sort of colonial yellow that echoes fife trills and drum cadences. Inside, visitors will find an impressive collection of Hudson River School and American Impressionist works for sale, including many by former residents of the Old Lyme Art Colony.

In a town saturated with art history, the Cooley Gallery, a half mile further down Lyme Street from the college, is an engine of the present, a commercial retail gallery that offers works of 19th- and early 20th-century representational art to the buying public. The gallery is housed in a late Federal-style converted carriage house that is painted the sort of colonial yellow that echoes fife trills and drum cadences. Inside, visitors will find an impressive collection of Hudson River School and American Impressionist works for sale, including many by former residents of the Old Lyme Art Colony.

A congenial atmosphere swells inside the Cooley Gallery’s canary walls. Unlike at many Manhattan galleries, visitors here are encouraged to browse around, move paintings into better light, and enjoy owner Jeff Cooley’s impromptu lectures on such subjects as the subtle distinction between the American Barbizon style and tonalism, or how the right frame can make a good piece great. When he shifts his weight onto his heels and folds his arms, you know you’re about to hear something special.

“What’s great about this,” he says, standing in front of a painting by William S. Robinson titled The Landing, “is that not only is it a fabulous example of a tremendous American Impressionist work, with its fleck brush strokes and bright colors, but it also shows a typically Old Lyme scene. ‘The Landing’ was the dock on the Lieutenant River right behind the Florence Griswold house. The river played a huge role in the social lives of the artists and was a major enticement to painters looking to spend their summers here. The artists boated together, went fishing together. Certain amorous adventures between the artists and their wives, not necessarily their own wives, may have influenced the development of the colony from a social standpoint. So, in addition to being a gorgeous painting, this is the scene where that all would have happened.” Hanging on either side of the Robinson are Old Lyme scenes by Charles Vezin and Frank Dumond. And next to those, Will Howe Foote, Frank Bicknell, Bruce Crane. And more, upstairs and downstairs.

Old Lyme today has a more colorful palette of artists than it did a century ago; the community now embraces not just painters but also sculptors, photographers, and writers, including best-selling author Luanne Rice. Artists frequently appear as characters in her books, and part of her novel, Safe Harbor, was inspired by a painting by Linden Frederick that she purchased from the Cooley Gallery. She smiles wistfully when she speaks about her hometown. “I grew up knowing I wanted to be a writer, inspired by Old Lyme’s light, by the golden marshes, the rocky shores, coves ringed by thick oaks and pines, mountain laurel covering the hillsides, the unmistakable scent of salt and honeysuckle. We grew up in awe of living in such a place, knowing that the artists came here in search of light and beauty. I feel so grateful and inspired, to be able to turn to Old Lyme again and again; it gives meaning to my work and my life.”

For Rice, as for all its artists past and present, Old Lyme is a fount and a refuge. The magic of the landscape endures.

Joseph Newman is an associate director at the Cooley Gallery. He is a native of Salem, Connecticut, and is currently a master’s degree candidate at Harvard University.

The author would like to express his utmost gratitude to the staffs of the Florence Griswold Museum, the Lyme Art Association, the Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts, and the Cooley Gallery for their generous assistance, especially Tammi Flynn, Liz Farrow, Anna Swain, Helen Barnett, Lorre Broom, and Nancy Pinney.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art history and landscape and environment on our Topics page.

Footnotes

[i] Estelle Riback, Henry Ward Ranger: Modulator of Harmonious Color (Fort Bragg: Lost Coast Press, 2000), 3.

[ii] Examining the path of Venus across the disk of the sun provided early astronomers with data to better calculate the distance between the Earth and the sun. See The Transits of Venus by William Sheehan and John Edward Westfall (Prometheus Books, 2004) for more information.

[iii] Jack Becker, Henry Ward Ranger and the Humanized Landscape (Old Lyme, Florence Griswold Museum, 1999), 12.

[iv] Becker, 15.

[v] Henry Ward Ranger’s description of Old Lyme is among his most-quoted utterances. It originally appeared in the New Haven Morning Journal and Courier on July 5, 1907, and was recently re-published in The Hog River Journal Winter 2005/2006 in Liz Farrow’s article The Spirit of Miss Florence Restored.

[vi] William H. Gerdts, “American Tonalism: An Artistic Overview,” in Tonalism: An American Experience, ed. William H. Gerdts, Diana Dimodica Sweet, and Robert R. Preato (New York: Grand Central Art Galleries, 1982), 19.

[vii] Jeff Anderson, “The Art Colony at Old Lyme,” in Connecticut and American Impressionism (Storrs: University of Connecticut, 1980), 123-124.