By Cathryn J. Prince

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., WINTER 2015/16

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

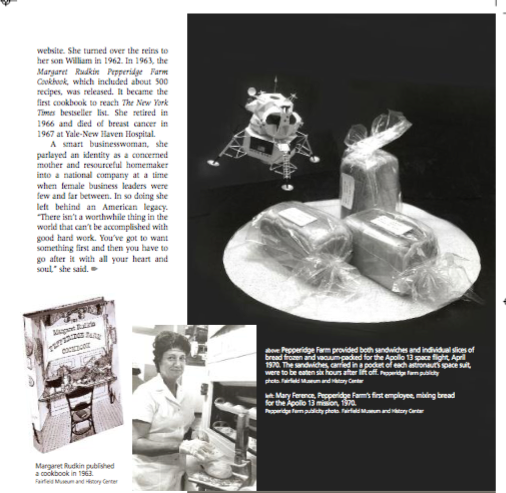

When the three Apollo 13 astronauts tucked into their sandwiches hours after liftoff, they were biting into more than fresh slices of Pepperidge Farm bread. They were sampling a slice of Connecticut history.

When the three Apollo 13 astronauts tucked into their sandwiches hours after liftoff, they were biting into more than fresh slices of Pepperidge Farm bread. They were sampling a slice of Connecticut history.

That was April 1970, 30 years after Margaret Rudkin founded Pepperidge Farm during the height of the Great Depression. By the time the astronauts headed to the moon the company was firmly ensconced in America’s cultural and culinary landscape, all because of one woman who, with ingenuity and perseverance—and in response to her child’s food allergies and her family’s economic need—transformed her kitchen business into a global enterprise.

Born in 1897 to James and Margaret Fogarty, Rudkin was the oldest of five children. Her father drove a truck for a living, and home was a brownstone on a quiet cobblestone street in New York City, in an area now known as Tudor City, according to the Margaret Rudkin Pepperidge Farm Cookbook (Atheneum Publishers, 1963). Dinnertime meant gathering around the table in her Irish-born grandmother’s large brick-floored kitchen. “No fancy stuff and sauces for us. Just plain, nutritious food with lots of bread and butter for the large family to be fed,” Rudkin later wrote of those simple meals.

After Rudkin’s grandmother died her family moved to Flushing, Queens. In high school she focused on math and finance and was class valedictorian. Rudkin continued studying math in college and upon graduation in 1915 landed a job in a bank. Several years later she went to work at McClure Jones & Co. as a customer representative in the office of Henry Albert Rudkin, a Wall Street broker 12 years her senior. Born in 1885, Henry grew up in New York City; his father Joseph hailed from Ireland, his mother Katherine was born in the United States.

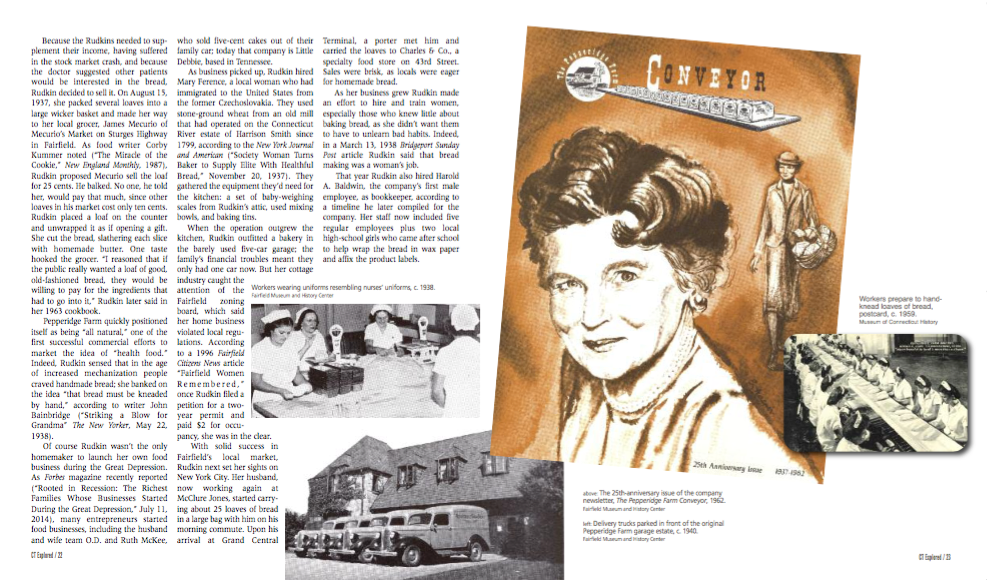

After the two wed in 1923 Margaret left McClure Jones for her new role as wife and, soon, mother; Henry, Jr. was born in 1924. William followed in 1926, Mark in 1929. In 1926 the family moved to Connecticut, purchasing a picturesque 123-acre farm in Fairfield, which they named Pepperidge Farm—named, according to the company’s website, for an ancient Pepperidge tree that grew on the property. “The ‘Farm’ part of the title wasn’t whimsy. They planned to lead a real country life. In fact, five hundred apple trees were planted as their first commercial venture in the country. And turkey raising was another,” according to the March 1973 issue of The Conveyer, Pepperidge Farm’s annual report.

Henry hired European craftsmen to build a farmhouse in the English Tudor style. Leaded glass windows graced the stone façade and a gabled slate roof capped the house, according to the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism’s historic resources inventory. There was a stable complex for 12 horses, and a large garage housed a fleet of cars.

The family’s first years in Connecticut kept a steady rhythm: Henry commuted to New York City, Margaret tended to her children and the home. And so it went until October 28, 1929, when the stock market crashed and left virtually no American unscathed. According to Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties (The Overlook Press, 2010), the market lost $14 billion in a single day. During this period a series of challenges befell the Rudkins: a grave polo accident left Henry unable to work for six months, the family finances fell into disarray, and, eight-year-old Mark began suffering from asthma. The child’s physician suggested additives in commercially processed foods might be exacerbating the boy’s condition.

According to Megan Elias in Food in the United States, 1890-1945 (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2009) commercially processed foods increasingly incorporated additives such as food coloring and saccharine. High fructose corn syrup and hydrogenated oils would join the list in time. Meanwhile, Americans increasingly consumed frozen and canned foods, and boxed cereals such as Kellogg’s Rice Krispies introduced in 1928. Also, commercially processed bread such as Wonderbread, which debuted May 21, 1921, was readily available to homemakers, according to The Wondercookbook (Ten Speed Press, 2007).

Rudkin heeded her physician’s advice and decided to bake her own bread. “Natural foods and natural sugars and the wheat germ contained in old-fashioned whole wheat bread might help this child who needed special food,” Rudkin later said in the March 1937 issue of Conveyor. Always analytical and methodical, Rudkin studied the history of bread making and scoured old books for recipes.

According to a 1938 Reader’s Digest article, the 40-year-old mother used her kitchen coffee grinder to mill flour from whole wheat she bought at a local feed store. And in her cookbook Rudkin admitted, “My first loaf of bread should have been sent to the Smithsonian Institution as a sample of Stone Age bread, for it was hard as a rock and about 1 inch high. So I started over again, and after a few more efforts by trial and error, we achieved what seemed like good bread.”

According to a 1938 Reader’s Digest article, the 40-year-old mother used her kitchen coffee grinder to mill flour from whole wheat she bought at a local feed store. And in her cookbook Rudkin admitted, “My first loaf of bread should have been sent to the Smithsonian Institution as a sample of Stone Age bread, for it was hard as a rock and about 1 inch high. So I started over again, and after a few more efforts by trial and error, we achieved what seemed like good bread.”

Because the Rudkins needed to supplement their income, having suffered in the stock market crash, and because the doctor suggested other patients would be interested in the bread, Rudkin decided to sell it. On August 15, 1937, she packed several loaves into a large wicker basket and made her way to her local grocer, James Mecurio of Mecurio’s Market on Sturges Highway in Fairfield. As food writer Corby Kummer noted (“The Miracle of the Cookie,” New England Monthly, 1987), Rudkin proposed Mecurio sell the loaf for 25 cents. He balked. No one, he told her, would pay that much, since other loaves in his market cost only ten cents. Rudkin placed a loaf on the counter and unwrapped it as if opening a gift. She cut the bread, slathering each slice with homemade butter. One taste hooked the grocer. “I reasoned that if the public really wanted a loaf of good, old-fashioned bread, they would be willing to pay for the ingredients that had to go into it,” Rudkin later said in her 1963 cookbook.

Pepperidge Farm quickly positioned itself as being “all natural,” one of the first successful commercial efforts to market the idea of “health food.” Indeed, Rudkin sensed that in the age of increased mechanization people craved handmade bread; she banked on the idea “that bread must be kneaded by hand,” according to writer John Bainbridge (“Striking a Blow for Grandma” New Yorker, May 22, 1938).

Of course Rudkin wasn’t the only homemaker to launch her own food business during the Great Depression. As Forbes Magazine recently reported (“Rooted in Recession: The Richest Families Whose Businesses Started During the Great Depression” July 11, 2014), many entrepreneurs started food businesses, including the husband and wife team O.D. and Ruth McKee, who sold five-cent cakes out of their family car; today that company is Little Debbie, based in Tennessee.

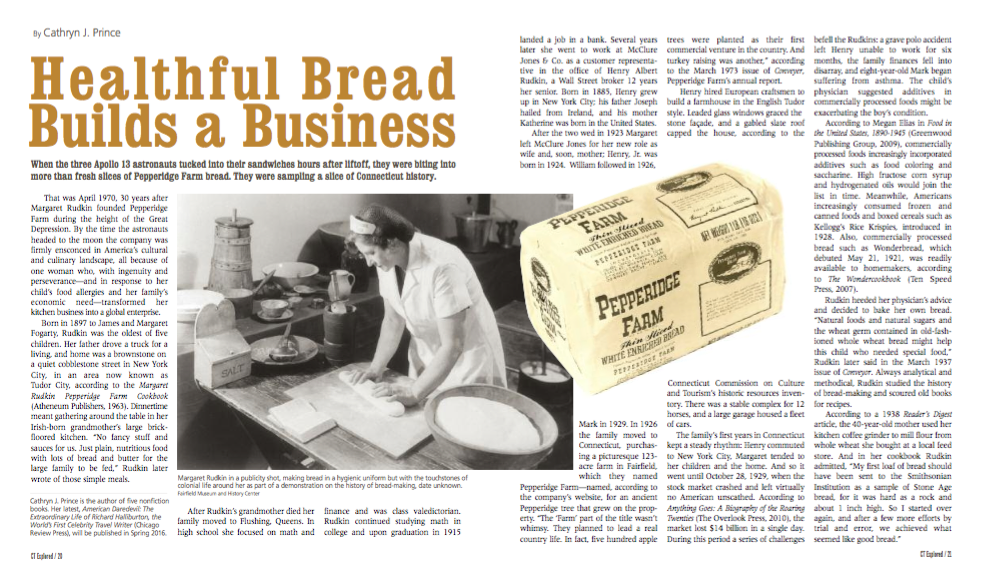

As business picked up, Rudkin hired Mary Ference, a local woman who had immigrated to the United States from the former Czechoslovakia. They used stone-ground wheat from an old mill that had operated on the Connecticut River estate of Harrison Smith since 1799, according to the New York Journal and American (“Society Woman Turns Baker to Supply Elite With Healthful Bread,” November 20, 1937). They gathered the equipment they’d need for the kitchen: a set of baby-weighing scales from Rudkin’s attic, used mixing bowls, and baking tins.

When the operation outgrew the kitchen, Rudkin outfitted a bakery in the barely used five-car garage; the family’s financial troubles meant they only had one car now. But her cottage industry caught the attention of the Fairfield zoning board, which said her home business violated local regulations. According to a 1996 Fairfield Citizens News article “Fairfield Women Remembered,” once Rudkin filed a petition for a two-year permit and paid $2 for occupancy, she was in the clear.

With solid success in Fairfield’s local market, Rudkin next set her sights on New York City. Her husband, now working again at McClure Jones, started carrying about 25 loaves of bread in a large bag with him on his morning commute. Upon his arrival at Grand Central Terminal, a porter met him and carried the loaves to Charles & Co., a specialty food store on 43rd Street. Sales were brisk, as locals were eager for homemade bread.

As her business grew Rudkin made an effort to hire and train women, especially those who knew little about baking bread, as she didn’t want them to have to unlearn bad habits. Indeed, in a March 13, 1938 Bridgeport Sunday Post article Rudkin said that bread making was a woman’s job.

That year Rudkin also hired Harold A. Baldwin, the company’s first male employee, as bookkeeper according to a timeline he later compiled for the company. Her staff now included five regular employees plus two local high-school girls who came after school to help wrap the bread in wax paper and affix the product labels.

In late winter 1938 Rudkin upgraded from her makeshift equipment to professional equipment. At $987, it was an expensive investment, Baldwin noted, but needed to turn out nearly 3,000 loaves a week. She bought the company’s first delivery truck, a half-ton Dodge panel truck, for $795. Harold Pennington became the company’s first full-time driver at $18 a week.

In spite of the Great Depression and a jobless rate that reached 17 percent in 1939, business thrived. Rudkin understood that consumers would still spend money; they just wanted to spend it wisely, according to an article in The Economist (“Thriving on Adversity,” October 1, 2009).

As the 1930s closed, numerous newspaper articles opened doors for the company. A 1939 Reader’s Digest article “Bread, de Luxe” noted, “this home-baked bread industry has presented the local community with a thriving business, 45 new jobs and an annual payroll in excess of $50,000.” The article further noted, “Born in a depression summer, when most people were thinking of retrenchment rather than expansion, conducted by a woman without previous business experience, it illustrates what wit and intelligence can do with an old idea.”

As the company expanded it added whole wheat bread with raisins, rye, pumpernickel, along with dinner rolls. Again Pepperidge Farm needed more space. In 1940, using $15,000 in borrowed capital, Rudkin relocated the company to the spacious former Packard showroom on Connecticut Avenue in Norwalk. She also leased the former Norwalk Hospital building. Walter Bradnee Kirby, the architect who designed the buildings on the original farm, designed the new facility, which boasted an in-house cafeteria, infirmary, and full-time nurse.

The company provided employee benefits—including six sick days pay per year—according to the Pepperidge Farm 1957 employee handbook. On their 10th anniversary, employees received a bonus equal to four weeks’ wages and a monogrammed sterling silver fruit bowl. The company threw an annual Christmas party featuring dinner, dancing, and entertainment, door prizes, and safe-driving awards for the truck drivers.

According to Baldwin Rudkin knew the name of every employee and paid better-than-average wages. Yet while Rudkin made it a practice to hire women, the wages she paid women lagged far behind those of their male counterparts. For example, in 1961 a male mixer had a starting salary of $2.15 an hour while a female mixer started at $1.75, according to the handbook.

The advent of World War II presented the company with many challenges, including the rationing of butter, flour, honey, sugar, and milk. Throughout the war Rudkin “obeyed every war measure to the letter,” Baldwin noted in The Conveyor. “The winning of the war was our primary object, but our secondary aim was to continue to maintain our high standards for quality of P.F. bread. The quantity of bread suffered, but never the quality.” Each time the bakery cut a pound of butter from a recipe, it substituted one-quarter cup of heavy cream. As both ingredients had the same butterfat content, nothing was lost in taste or quality, according to Baldwin, who pointedly recalled that flour was in such short supply they had to scrape the bottom of the flour bins.

By the late 1950s Henry Rudkin had quit his Wall Street job and begun managing marketing and finances for Pepperidge Farm. While he would play a key role in the business, especially in its early years, Margaret would always be the public face of the company. During this decade Pepperidge Farm acquired Black Horse Frozen Pastry Company of Keene, New Hampshire. Coffee cake and Melba toast were also introduced.

By the late 1950s Henry Rudkin had quit his Wall Street job and begun managing marketing and finances for Pepperidge Farm. While he would play a key role in the business, especially in its early years, Margaret would always be the public face of the company. During this decade Pepperidge Farm acquired Black Horse Frozen Pastry Company of Keene, New Hampshire. Coffee cake and Melba toast were also introduced.

Meanwhile, Margaret started accruing awards. In 1955 the Women’s International Exposition presented her with an “Award to Industry” for outstanding achievement. In 1956 she was named one of the “Famous Seven” best-known women executives in the United States, and after her retirement in 1962, she lectured at Harvard Business School and spoke before Wall Street groups and at the International Institute of Business Administration at Fontainebleau, France. Fortune Magazine included Rudkin on a list of 50 most powerful businesswomen in the period from 1950 to 1960.

Rudkin introduced other goods and products, most famously cookies in 1955. The “European” varieties were produced by agreement with manufacturer Delacre from Belgium. She sent bakers there to train and imported a 150-foot oven from Belgium. Milanos and Brussels were the first of the “Distinctive Cookie” line to hit the shelves. The “Old-fashioned” line, which included chocolate-chip and oatmeal cookies, arrived in 1957. As the food writer Corby Kummer wrote, the cookies were cleverly marketed as being “old-fashioned”—in reality no old-fashioned recipe used as much sugar or raisins or yielded as soft a cookie as Pepperidge Farm’s.

When the Camden, New Jersey-based Campbell Soup Company purchased Pepperidge Farm from Rudkin in 1961 for $28 million, Rudkin became the first woman to sit on Campbell Soup’s board. But she stayed at the helm, introducing the Goldfish cracker in 1962, having found the recipe on a 1958 trip to the Swiss biscuit manufacturer Kambly, according to the company website. She turned over the reins to her son William in 1962. In 1963, the Margaret Rudkin Pepperidge Farm Cookbook, which included about 500 recipes, was released. It became the first cookbook to reach the New York Times bestseller list. She retired in 1966 and died of breast cancer in 1967 at Yale-New Haven Hospital.

A smart businesswoman, she parlayed an identity as a concerned mother and resourceful homemaker into a national company at a time when female business leaders were few and far between. In so doing she left behind an American legacy. “There isn’t a worthwhile thing in the world that can’t be accomplished with good hard work. You’ve got to want something first and then you have to go after it with all your heart and soul,” she said.

Cathryn J. Prince is the author of five nonfiction books. Her latest, American Daredevil: The Extraordinary Life of Richard Halliburton, the World’s First Celebrity Travel Writer(Chicago Review Press), will be published in Spring 2016.

Explore!

For more information about Pepperidge Farm see the E. Lee Schneider Pepperidge Farm Collection and the Henry and Margaret Rudkin Collection at the Fairfield Museum & History Center, 370 Beach Road, Fairfield. Fairfieldhistory.org, 203-229-1598

WATCH the Connecticut Old State House’s Conversations at Noon program featuring the Pepperidge Farm story!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Food History on our TOPICS page.