By Jerry Roberts

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Summer 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Sometimes preservation means more than just conserving what you have. Sometimes it’s about re-building and even recreating what once was.

Sometimes preservation means more than just conserving what you have. Sometimes it’s about re-building and even recreating what once was.

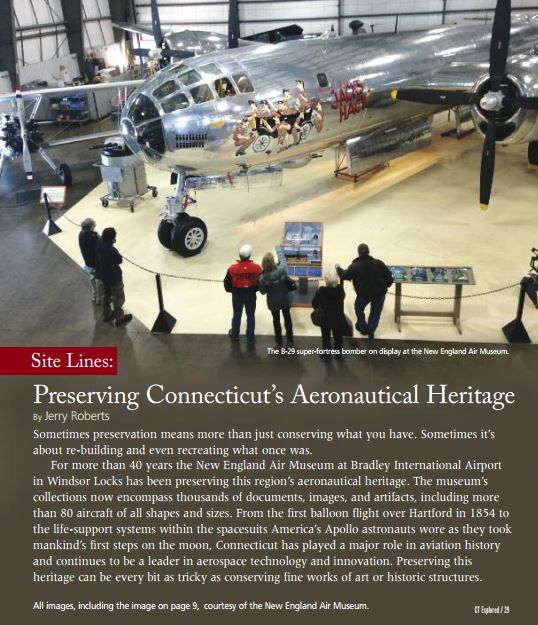

For more than 40 years the New England Air Museum at Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks has been preserving this region’s aeronautical heritage. The museum’s collections now encompass thousands of documents, images, and artifacts, including more than 80 aircraft of all shapes and sizes. From the first balloon flight over Hartford in 1854 to the life support systems within the spacesuits America’s Apollo astronauts wore as they took mankind’s first steps on the moon, Connecticut has played a major role in aviation history and continues to be a leader in aerospace technology and innovation. Preserving this heritage can be every bit as tricky as conserving fine works of art, or historic structures.

It’s easy to understand the challenges of preserving early flying machines (a project we’re undertaking; read on), but even relatively modern aircraft pose major conservation dilemmas. Seemingly stable aluminum is subject to corrosion, while Plexiglas canopies can become crazed and milky with long-term exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light. Rubber, leather, and early plastic components dry, crack, and decompose. Many aircraft also contain a variety of hazardous materials such as asbestos insulation and radium-painted cockpit instrumentation, all of which must be removed during the restoration process.

The New England Air Museum (NEAM) has been able take on several major restoration projects because of its dedicated group of more than 150 volunteers. While many of these volunteers are highly skilled craftsmen retired from Connecticut’s aviation industry, others come from a variety of walks of life, each bringing his or her own unique experience to the team.

Two of the largest aircraft preservation projects carried out in Connecticut are the restorations of a B-29 super-fortress bomber built in 1944 and the last of the great American four-engine flying boats, the Sikorsky VS-44a built in 1940. The B-29 sat outside, exposed to the elements, for decades and was nearly destroyed by a tornado in 1979 before being completely rebuilt by NEAM volunteers. Originally built in Bridgeport, the VS-44 had an impressive career that spanned WWII, post-war trans-Atlantic passenger service, and niche services to Iceland, South America, Catalina Island, and the Caribbean. In 1968 it was damaged after running aground in St. Thomas, where it was abandoned and suffered from extensive exposure to the corrosive tropical environment. It was at last brought back to Connecticut and completely refurbished by a team of more than 100 retired Sikorsky workers, many of whom had originally helped build it. Volunteers logged more than 300,000 hours during the 10-year restoration project.

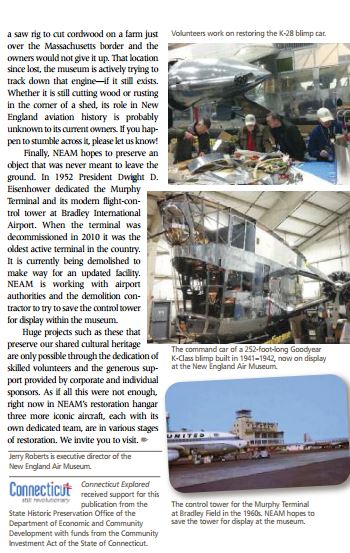

In the same giant hangar where the VS-44 is now on view, another great airship is being restored by its own dedicated team: the command car of a 252-foot-long Goodyear K-Class blimp built in 1941− 42. The K-28 was one of the original airships with which Goodyear pioneered the technology of illuminated aerial advertising that is now a familiar presence over cities and sports stadiums around the world. But Goodyear originally manufactured the K-Class blimps for the United States Navy to escort Allied convoys and search for German U-boats off shore during World War II. With a crew of 10, these massive, helium-filled sentinels carried radar, sonar buoys, aerial bombs, and a 50-caliber machine gun for self-defense. All of this equipment was later stripped out as Goodyear put the blimps into civilian use.

After the K-28’s retirement and ensuing decades of deterioration, NEAM volunteers spent more than two decades meticulously researching and restoring the last surviving example of a U.S. Navy K-Class blimp car to its original configuration. This required finding two replacement Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines and their Hamilton Standard propellers, creating new aluminum engine cowlings, and refabricating dozens of missing Plexiglas windows and much of the interior, including crew stations and bunks, replicated galley, navigation and radar equipment, sonar buoys, bombs, and the machine-gun turret. Although the restoration will not be completed for at least another year, visitors can watch its progress.

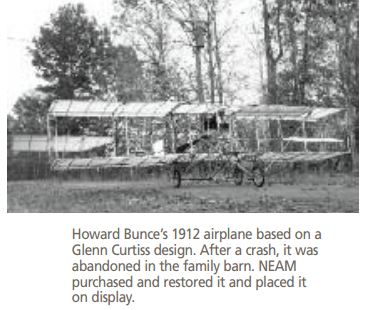

Some projects may never reach completion due to factors beyond our control. In 1910 in New Britain, Charles Hamilton made the first documented public airplane flight in Connecticut, flying a machine designed and built by legendary aviator Glenn Curtiss. Seventeen-year-old Howard Bunce of nearby Berlin wanted to be part of this new air age, too, and cobbled together his own version of a Curtiss Pusher. His attempts at flight at the Berlin Fair Grounds in 1912 were not very successful, but they were among the first made by an aircraft built in this state. After a crash the components of his flying machine were relegated to the family barn on Worthington Ridge, where he built a second machine that was no more successful than the first.

Some projects may never reach completion due to factors beyond our control. In 1910 in New Britain, Charles Hamilton made the first documented public airplane flight in Connecticut, flying a machine designed and built by legendary aviator Glenn Curtiss. Seventeen-year-old Howard Bunce of nearby Berlin wanted to be part of this new air age, too, and cobbled together his own version of a Curtiss Pusher. His attempts at flight at the Berlin Fair Grounds in 1912 were not very successful, but they were among the first made by an aircraft built in this state. After a crash the components of his flying machine were relegated to the family barn on Worthington Ridge, where he built a second machine that was no more successful than the first.

In 1962 what was left of the original flying machine was found in the Bunce family barn and was later purchased by the New England Air Museum. The decades-long restoration project, which involved combining surviving parts with meticulously re-fabricated missing components, began in 1966 under NEAM volunteer George Pranaitis and continued by others through 1992. Though the machine is now on display at the museum, its restoration was never truly completed because the museum was not able to secure the engine that had powered the aircraft. According to the NEAM volunteer Dick Everett, when he eventually tracked it down the engine was being used to power a saw rig to cut cordwood on a farm just over the Massachusetts border and the owners would not give it up. The museum is actively trying to track down that engine—if it still exists. Whether it is still cutting wood or rusting in the corner of a shed, its role in New England aviation history is probably unknown to its current owners. If you happen to stumble across it, please let us know!

Finally, NEAM hopes to preserve an object that was never meant to leave the ground. In 1952 President Dwight D. Eisenhower dedicated the Murphy Terminal and its modern flight-control tower at Bradley International Airport. When the terminal was decommissioned in 2010 it was the oldest active terminal in the country. It is currently being demolished to make way for an updated facility. NEAM is working with airport authorities and the demolition contractor to try to save the control tower for display within the museum.

Huge projects such as these that preserve our shared cultural heritage are only possible through the dedication of skilled volunteers and the generous support provided by corporate and individual sponsors. As if all this were not enough, right now in NEAM’s restoration hangar three more iconic aircraft, each with its own dedicated team, are in various stages of restoration. We invite you to visit

Jerry Roberts is executive director of the New England Air Museum.

Explore!

New England Air Museum

36 Perimeter Road, Windsor Locks

Neam.org, 860-623-3305

LISTEN! Grating the Nutmeg podcast Episode 14: Before BDL: Bradley Field and Eugene Bradley

41 Minutes. Release Date: September 6, 2016

What’s the history of Bradley International Airport and why is it named for someone from Oklahoma? Is it time to change the name? On the 75th anniversary of Bradley Field (almost to the day) CT Explored’s Elizabeth Normen spoke with Jerry Roberts of the New England Air Museum about the past, present, and future of Connecticut’s international airport and air museum. The last of our episodes from the Summer 2016 issue “Small Towns, BIG Stories.”

READ MORE:

Windsor Locks: Bradley International Airport

Sikorsky: Still Revolutionary

Frederick Rentschler: The Sky’s the Limit

The Rise and Fall of Balloonist Silas Brooks

![]() Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.