By Diane C. Hassan

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Summer 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For more than a hundred years, an Oglala Lakota Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota named Cetan Kokipa — “Afraid of Hawk” in English—would lie in an unmarked grave in Danbury, Connecticut, on a hillside, overlooking a pond. It wasn’t until 2008 that he began his final journey home.

According to the Indian Census Rolls 1885 -1940, Albert Afraid of Hawk was born sometime between 1879 and 1881 on the Great Sioux Reservation. He was the third son of Emil Afraid of Hawk and his wife, White Mountain . His birth came at a time of tremendous cultural change for the Plains Indians. His father Emil survived the tragedy at the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876, and his older brother Richard lived through the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. The arrival of the transcontinental rail road in South Dakota, the scarcity of buffalo resulting from westward expansion and settlement, and the U.S. government’s development of the reservation system for containing Native American populations all played roles in the Lakota people’s drastic departure from traditional ways of life at the turn of the 20th century.

According to the Indian Census Rolls 1885 -1940, Albert Afraid of Hawk was born sometime between 1879 and 1881 on the Great Sioux Reservation. He was the third son of Emil Afraid of Hawk and his wife, White Mountain . His birth came at a time of tremendous cultural change for the Plains Indians. His father Emil survived the tragedy at the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876, and his older brother Richard lived through the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. The arrival of the transcontinental rail road in South Dakota, the scarcity of buffalo resulting from westward expansion and settlement, and the U.S. government’s development of the reservation system for containing Native American populations all played roles in the Lakota people’s drastic departure from traditional ways of life at the turn of the 20th century.

The 1898 Indian census shows 19-year-old Albert living on the Pine Ridge Reservation with his grandfather Slow Bull, next door to his parents and siblings. Some time in the months that followed, Albert made his way to Omaha, Nebraska. Evidence shows his presence there was related either to the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition or the Indian Congress, both of which were held in Omaha from June 1 to November 1, 1898.

The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition was a gathering much like a World’s Fair. It was meant to showcase the western region from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast and to attract tourists and economic opportunities to that part of the country. The Indian Congress, the largest assemblage of Native Americans up to that time, was part of the exposition. Visitors were able to witness first-hand the life style of American Indians.

More than 500 Indians representing 35 different tribes gathered for the Indian Congress; 88 were members of the Sioux tribe, and 10 were from the Pine Ridge Reservation, according to the congress secretary’s report. The gathering was well documented by journalists and others who clamored to take photos of American Indians. The report describes“… the Indians being photographed in costume in tribal groups and singly, in bust, profile, and full length, resulting in a series of several hundred pictures forming altogether one of the finest collections of Indian portraits in existence.”

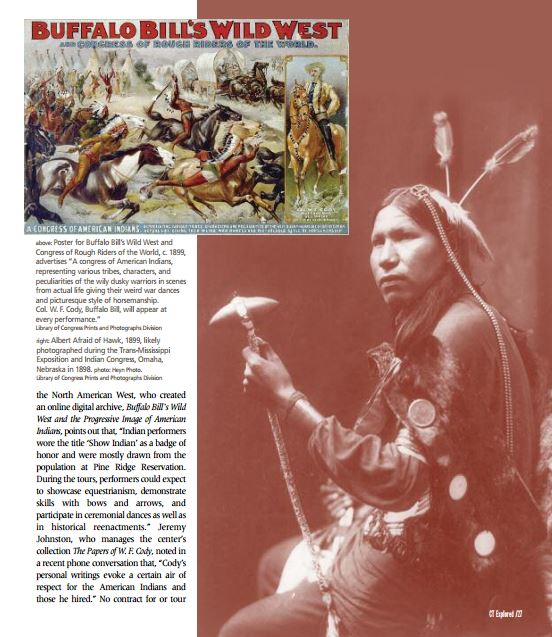

Several formal portraits of Afraid of Hawk, attributed to Heyn Photo and now in the collections of the Library of Congress and the Denver Public Library, verify his presence in Omaha. He might have been one of the delegates to the Indian Congress, or he may have been employed as a “show Indian” during the “Cody Day” celebrations that took place on August 31, 1898 as part of the exposition. An official exposition program reported “An assemblage of twenty-five thousand people or more, congregated within the grounds of the exposition,” by which Colonel William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was honored on the site where the first official performance of his Wild West show had been held 15 years earlier.

Before motion pictures became popular, outdoor entertainments such as the Wild We st show brought romance, excitement, and wonder to cities and towns across the United States. Paul Fees, former curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum, writes in his essay “Wild West Shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” (available on the Buffalo Bill Center of the West Website),“ In 1899, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West [show]covered over 11,000 miles in 200 days giving 341 performances in 132 cities and towns across the United States. In most places, there would be a parade and two two-hour performances.”

Records in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming show that in 1899 those hired by Buffalo Bill earned $25 per month, roughly equivalent to $679 in 2012. Jason Heppler, a historian of the North American West, who created an online digital archive, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians, points out that, “ Indian performers wore the title ‘Show Indian’ as a badge of honor and were mostly drawn from the population at Pine Ridge Reservation. During the tours, performers could expect to showcase equestrianism, demonstrate skills with bows and arrows, and participate in ceremonial dances as well as in historical reenactments.” Jeremy Johnston, who manages the center’s collection The Papers of W. F. Cody , noted in a recent phone conversation that, “Cody’s personal writings evoke a certain air of respect for the American Indians and those he hired.” No contract for or tour roster listing Afraid of Hawk has been located, but a photograph in the center’s collection shows him and a group of fellow Show Indians.

On June 28, 1900, hundreds of performers and employees of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World arrived in Danbury, Connecticut for afternoon and evening performances. The production had already made stops in Hartford, New Haven, and South Norwalk. For several days the show had been crippled by illness, with nearly 50 performers suffering from symptoms of food poisoning. Upon reaching Danbury, the condition of 20-year-old Albert was the most grave. In a sad twist of fate, members of the show had eaten tainted canned corn and contracted botulism. The July 2 edition of The New Haven Register reported on the events leading up to Albert’s death, under the headline “He Fell Victim to Modern Civilization. Canned Corn Killed Him.”

Albert Afraid of Hawk, 1899, likely photographed during the Trans-Mississippi Exposition and Indian Congress, Omaha, Nebraska in1898. photo: Heyn Photo. Libray of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Johnny Baker, the adopted son of Cody and manager of the show, visited the teepees of the Sioux Indians and he found Afraid of Hawk deathly sick. He insisted that a physician should be called and after a consultation, the chiefs, one of whom was the famous Black Hawk, decided that a white medicine man should do what he could to relieve the Indian’s suffering. … Johnny Baker came again while the doctor was there. When he heard that it would be impossible for the sick Indian to accompany the show to Pittsfield he asked that he be taken to the hospital. “Spare no expense,” he said to the physician. “Save his life, no matter what the cost may be.” As he was lifted to the wagon, Afraid of Hawk called one of the chiefs to his side and spoke a few wordsin his native tongue. “He says he is going to die,” said the interpreter, turning to the doctor, “and he is bidding the other members of the tribe farewell.” …The advent of the Indians caused a ripple of excitement at the hospital. The interpreter … took a seat close by the bed of the sick man. The stalwart form of Afraid of Hawk was convulsed with pain but he made no complaint. … A few minutes before 10 o’clock he sank into a stupor and died.

The Danbury Evening News ran an account of Afraid of Hawk’s burial:

By the side of a new made grave in Wooster Cemetery, Friday afternoon, stood a lone Indian. He stood with head bowed and bare as he watched the remains of his dearestfriend, Man Afraid of Hawk, being lowered to their last resting place on the banks of the sleepy little pond in the center of the necropolis…ina plot purchased for the purpose by the proprietors of the show. Rev. J.D. Skene, pastor of St. James’ church, performed the ceremony using the simple touching ritual of the Episcopal church. David Bull Bear took his place at the head of the casket ….

In 2008, Robert Young, then superintendent of Wooster Cemetery, was re-mapping the cemetery. He came across a burial card for Section 22 for an individual named “Afraid of Hawke.” Young had heard the rumors that an Indian from the Buffalo Bill Wild West show had been buried there, and this document confirmed those rumors. Young enlisted research assistance from The Danbury Museum & Historical Society, of which he was then board president, and the rediscovery of the story of Afraid of Hawk began to come together. A death certificate filed in the City of Danbury town clerk’s office listed Afraid of Hawk’s occupation: Rough Rider. Young eventually located descendants, including 84-year-old Daniel Afraid of Hawk, Albert’s last living nephew, who lives on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation.

Family members knew that Albert had joined the Wild West show and never returned. Young was able to fill in some unknowns for them during his initial visit to Pine Ridge Reservation in 2010. Discussions then began with Daniel and the tribal council to start the repatriation process and return Afraid of Hawk’s remains to his family and homeland.

In November 2011, Marlis Afraid of Hawk, Daniel’s daughter, grew impatient. She was troubled about whether the endeavor would succeed, until she had a dream. In the dream, “I was 5 or 6 years old,” she recalled to a group gathered at Danbury Hospital during her visit for the excavation in 2012. “My siblings and parents were gone and I was scared. So, I went outside to look forthem butthey were nowhere in sight. I saw this person coming from the north. He had long hair, but I didn’t recognize his face. I went back into our house and heard him playing a flute. The sound was very comforting. When he stopped, I went back outside. I heard him clearly, he said: ‘Yu` pah,’ it means come here. He waved and suddenly the clouds came together. Many horses—pintos, palominos—and then the Lakota people stepped down from the clouds. The grandmothers, the grandfathers, the children… and even a dog with travois [a kind ofsled], and then the warriors on horseback.”

After attending a ceremony with tribal elders, Marlis explained, she understood her dream’s meaning. The Lakota who came from the sky were her ancestors, and the man with the long hair was Albert. It wasthis vivid vision that propelled the repatriation effort forward. Marlis took the lead and contacted Young. Marlis, her father Daniel, and her brother John Afraid of Hawk, along with Richard Red Elk, a distant cousin who was enlisted by the tribal council to serve as their driver, set out on their 1,700-mile journey to Danbury.

On Tuesday, August 14, 2012, Nicholas Bellantoni, Connecticut’sstate archaeologist (See “Right Down the Street…” page 20.), arrived at Wooster Cemetery to begin the excavation and learned that the family would be present. He would spend roughly one week at the cemetery with relatives and strangers holding vigil at the graveside and participating in traditional Lakota rituals. Despite his experience with countless excavations, archaeological digs, and exhumations during a 40-year career, Bellantoni felt an added pressure that day. “I wasn’t very confident that there’d be something forthem to bringhome,” admitted Bellantoni in a recent phone interview. “I wanted to prepare them in advance that there was a good chance that remains wouldn’t be found.” Initial soil testing had confirmed the acidity of the soil and thus the slim likelihood of finding organic remains. As the work progressed, sage and sweet grass, placed near photos of Albert, were tended by John and burned continuously. Pipes were passed, drums beaten, songs sung, and stories told. Throughout the process, Bellantoni was in constant discussion with the family about his procedures and findings.

procedures and findings. “I remember talking to Albert and asking him, ‘Please behere.’I’dnever begged like that,” he confessed. Assisting Bellantoni were Bruce Greene and other volunteers from the Friends of the Office of State Archaeology and Dr. Gary Aronsen, a forensic and biological anthropologist from Yale University. Also present were Bob Young and his wife Mary Jo, Tania Porta, who was the funeral director in charge of remains, and Wendell Deer with Horns, a Lakota Sioux living in Connecticut who was instrumental in assisting the family. State officials representing the Native American community in Connecticut, cemetery personnel, reporters, photographers, and curious onlookers came and went each day.

After an excavator stripped away the topsoil to a depth of two feet, the dirt was removed four inches at a time and screened. A metal detector was used as the team descended into a very narrow excavation space. That space was tight, as they didn’t want to disturb the plots lying on either side. When the excavation reached four feet, pings began to emanate from the detector, and the team switched to hand tools. They soon unearthed white plated metal handles and then nails from the upper board of the coffin. “I could tell from the handles that it wasn’t a top-of-the-line coffin for the period but that it was made from hardwood. Buffalo Bill had taken care of Albert,” Bellantoni said.

Bellantoni decided to concentrate on one end of the plot to determine if skeletal remains were present there. The Danbury Evening News account of Albert’s burial noted that he was laid to rest in a Christian pattern, with his head to the west. Physical evidence, such as nails from the bottom coffin board, emerged, yet no human remains had appeared. Delicate scraping with a trowel revealed an object about the size of a 50-cent piece. It was part of a skull. “He’s here,” Bellantoni exclaimed to those holding vigil nearby. Once the cranium was exposed, the daunting task of removal began. Bellantoni explained, “Small roots ran throughout the interior of the skull, which was packed with moist wet soil. There was a risk of it exploding and/or crumbling during removal. It was so fragile, my heart was in my throat,” he later reported.

Bellantoni decided to concentrate on one end of the plot to determine if skeletal remains were present there. The Danbury Evening News account of Albert’s burial noted that he was laid to rest in a Christian pattern, with his head to the west. Physical evidence, such as nails from the bottom coffin board, emerged, yet no human remains had appeared. Delicate scraping with a trowel revealed an object about the size of a 50-cent piece. It was part of a skull. “He’s here,” Bellantoni exclaimed to those holding vigil nearby. Once the cranium was exposed, the daunting task of removal began. Bellantoni explained, “Small roots ran throughout the interior of the skull, which was packed with moist wet soil. There was a risk of it exploding and/or crumbling during removal. It was so fragile, my heart was in my throat,” he later reported.

Examination of the skeletal remains confirmed that Afraid of Hawk had ridden horses bareback style, and an intact incisor exhibited distinct characteristics unique to Native Americans. Remnants of the fabric used as a burial shroud were unearthed along with the straight and safety-style pins that had fastened the sheet closed. Surprisingly, hair fibers were discovered, along with three copper beads. As Bellantoni explained, “The copper from the beads and an earring that had been worn in Albert’s left ear neutralized the soil acidity and enhanced the organic presentation.”

Albert Afraid of Hawk was laid to rest according to the Lakota tradition, at the Pine Ridge Reservation, near Manderson, South Dakota, 2012. Photo by Mary Jo Young

The remains of the Afraid of Hawk family’s long-missing “lala” (meaning “grandfather” and used both as a familial designation and title of honor) and all of the artifacts retrieved from his grave were prepared and returned to South Dakota for reburial. At the close of their visit, the family bestowed Lakota names upon several people integral to the project. For Bellantoni, they chose the name Tāku wan Waste’ Okīlē, which means “He Who Finds Good.” They then left Danbury, knowing Albert would follow them home shortly.

Back in South Dakota, Albert’s remains were wrapped in a buffalo hide and placed upon a scaffold, along with food for his family in the spirit world. Daniel sang Lakota songs, and a smudging ceremony was held to bless Albert on the next phase of his journey. After being separated from his people for more than a century, Albert Afraid of Hawk now rests in his homeland with the ancestors.

Explore!

Read more stories about Native Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

“12,500-Year-Old Paleoindian Site Discovered”

“State Archaeologist on 30 Years of Great Finds“