by Leah S. Glaser

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2016/17

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This article is adapted form Leah S. Glaser and Nicholas Thomas, “Sam Colt’s Arizona: Investing in the West,” Journal of Arizona History 56:1 (Spring 2015), 29-52.

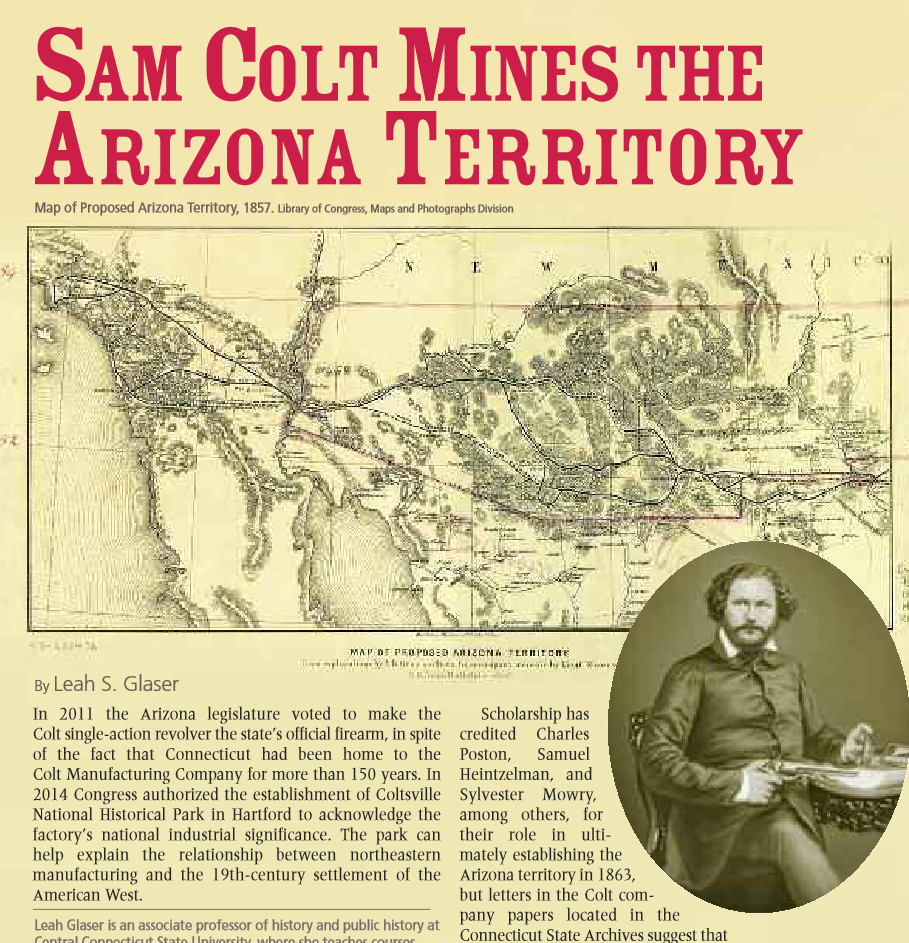

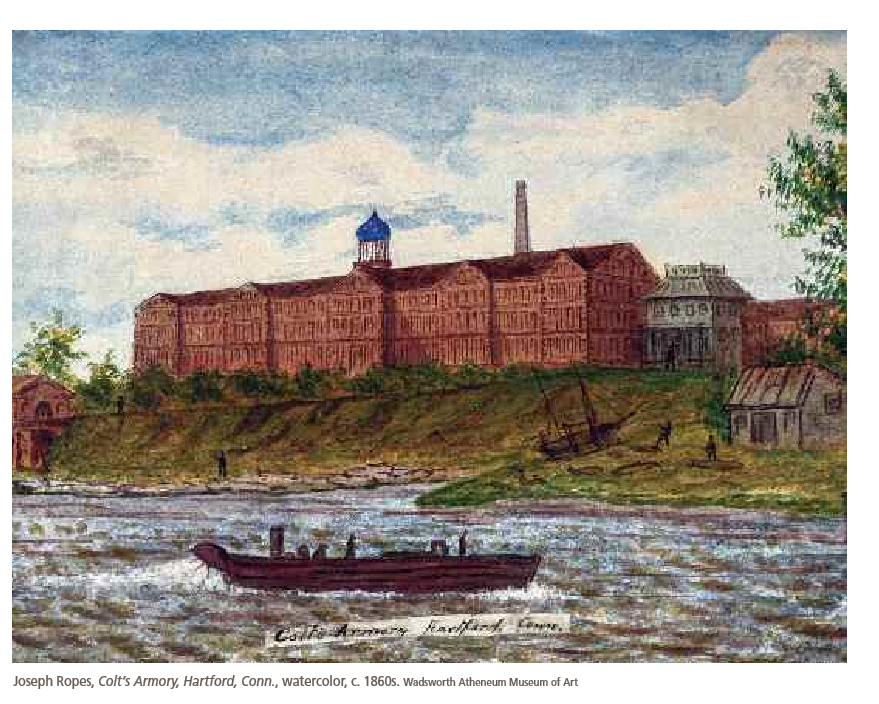

In 2011 the Arizona legislature voted to make the Colt single-action revolver the state’s official firearm, in spite of the fact that Connecticut had been home to the Colt Manufacturing Company for more than 150 years. In 2014 Congress authorized the establishment of Coltsville National Historical Park in Hartford, Connecticut to acknowledge the factory’s national industrial significance. The park can help explain the relationship between northeastern manufacturing and the 19th-century settlement of the American West.

Scholarship has credited Charles Poston, Samuel Heintzelman, and Sylvester Mowry, among others, for their role in ultimately establishing the Arizona territory in 1863, but letters in the Colt company papers located in the Connecticut State Archives suggest that Samuel Colt also played a key role, without ever actually traveling there. Born in Hartford in 1814, Colt was an inventor, businessman—and opportunist.

Colt patented his first revolver during the Texas Revolution in 1836 and marketed it to Western settlers. But before the Civil War and the 1873 introduction of the “gun that won the West” –a reputation it gained in popular culture (along with the Winchester) — Colt invested in American mining interests and lobbied Congress to politically stabilize the region. Although confined to Hartford with health problems, Colt served as the financier, financial advisor, and eventual director of the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company in the Arizona Territory. It ultimately failed as a business venture, but Colt and the company promoted the economic and political foundations for the region 2,600 miles from his Hartford, Connecticut home.

Reports of mineral wealth in the American Southwest had proliferated since Spain’s Francisco Vásquez de Coronado traveled through the region in 1540 – 1541. Explorer Zebulon Pike’s 1810 report to Thomas Jefferson about his 1803 expedition sent Americans scrambling for gold and silver deposits into what was then Spanish territory. After Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821, Americans took advantage of the trade and commerce moving north, along the Camino Real, from Mexico City.

During and after the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, the occupying American army further boosted the regional economy. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the war, ceded New Mexico territory to the United States. But it was the 1854 Gadsden Purchase, acquired to encourage trade with Mexico, that invited American mining interests into southern Arizona. The local Apaches first welcomed the U.S. military as allies against the Mexicans, but they eventually turned hostile with increased American presence.

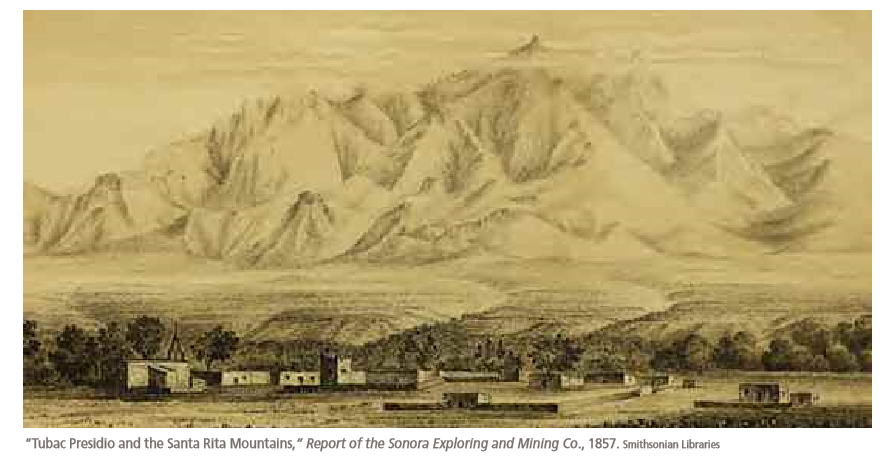

Following the California Gold Rush (around 1850), Kentucky native Charles Debrille Poston joined an expedition with German engineer Herman Ehrenberg to investigate the area recently acquired as part of the Gadsden Purchase. In his 1915 volume History of Arizona (Filmer Brothers), historian Thomas Farish mentions that the Texas and Pacific Railroad Company gave Poston and Ehrenberg $100,000 to open mines in the new territory. They established their headquarters at the abandoned Tubac presidio and purchased a nearby 17,000-acre ranch. After meeting career military man Major Samuel Heintzelman at Fort Yuma, the fort commander persuaded optimistic Midwestern capitalists interested in the Southwest to incorporate the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, a joint stock company, to take over abandoned Mexican silver mines and purchase land for American settlement. Poston would serve as manager, and Heinzelman as president.

Unfortunately, these pioneers underestimated the political, cultural, and environmental challenges in southern Arizona. Convinced by engineers’ reports that the region held rich silver ore deposits, Heintzelman and former military and now mining entrepreneur Sylvester Mowry urged the U.S. Congress to create a southern (Arizona) territory, separate from New Mexico, in order to procure more government resources. Still, stockholders refused to provide additional funds until Poston and his partners produced better results. Then Major William Chapmen, a West Point schoolmate of Heintzelman with mining interests in Mexico, introduced Heinzelman to Samuel Colt, who was looking to invest in Arizona mining.

The Cincinnati shareholders approved Colt’s offer of $10,000 in cash and $10,000 worth of firearms in exchange for $100,000 in company stock. With Colt’s help, the company intended to arm every one of its miners. Factory ledgers indicate that the Colt Manufacturing Company sent about 600 pistols and 30 rifles to Tubac, along with enough interchangeable parts to meet any contingency. Upon receiving Colt’s check on January 1, 1858, Heintzelman announced, “our troubles are over.” In February 1858, Colt accompanied Mowry and Heintzelman to Washington to support a resolution to create a new Arizona territory with a north-south border along the 109th meridian, reserving northern Arizona as Indian territory.

From 2,600 miles away, Colt attempted to insert himself in the management of the company. By letter, he offered advice on internal operations, made business introductions, and networked on behalf of the company. He furnished equipment and supplies. He offered to send more money for transportation and supplies and to hire a surveyor, carpenters, and a wheelwright, requesting additional company stock in return.

Yet even after his election to the board of directors in March 1858, he confided to Heintzelman that he felt like an outsider. Heintzelman was the only person in the company he knew personally.. He pushed Heintzelman hard, in his correspondence and by leveraging his cash flow, to make something happen at the mines. “Please let me hear from you constantly,” he implored, “and report all your and the company’s movements. If any members of the Company from the mines, or elsewhere, or any personal friends of yours, come to the East, give them introductions … I want to be fully posted.”

Unsatisfied, Colt sent a trusted proxy from Hartford to be his eyes and ears: his brother-in-law, Richard Jarvis. Jarvis was appointed company treasurer and left for Arizona in the summer of 1858. Jarvis was young and inexperienced, but his family was excited about the personal and financial opportunities the new position promised. “[I]f he stays in that country long enough I have no doubt he will acquire influence, station, and fortune,” Jarvis’s father William boasted.

Colt also urged Heintzelman to take a leave of absence from the military to inspect and report on the Arizona operations in person. Colt approached the former and current secretaries of war, Jefferson Davis and John Floyd, respectively, to grant Heintzelman a 12-month leave. He funded Heintzelman’s travel to Arizona, pledging to “make the necessary advances,” and presented him with a new revolver at a dinner in New York City on the eve of the trip.

Colt also urged Heintzelman to take a leave of absence from the military to inspect and report on the Arizona operations in person. Colt approached the former and current secretaries of war, Jefferson Davis and John Floyd, respectively, to grant Heintzelman a 12-month leave. He funded Heintzelman’s travel to Arizona, pledging to “make the necessary advances,” and presented him with a new revolver at a dinner in New York City on the eve of the trip.

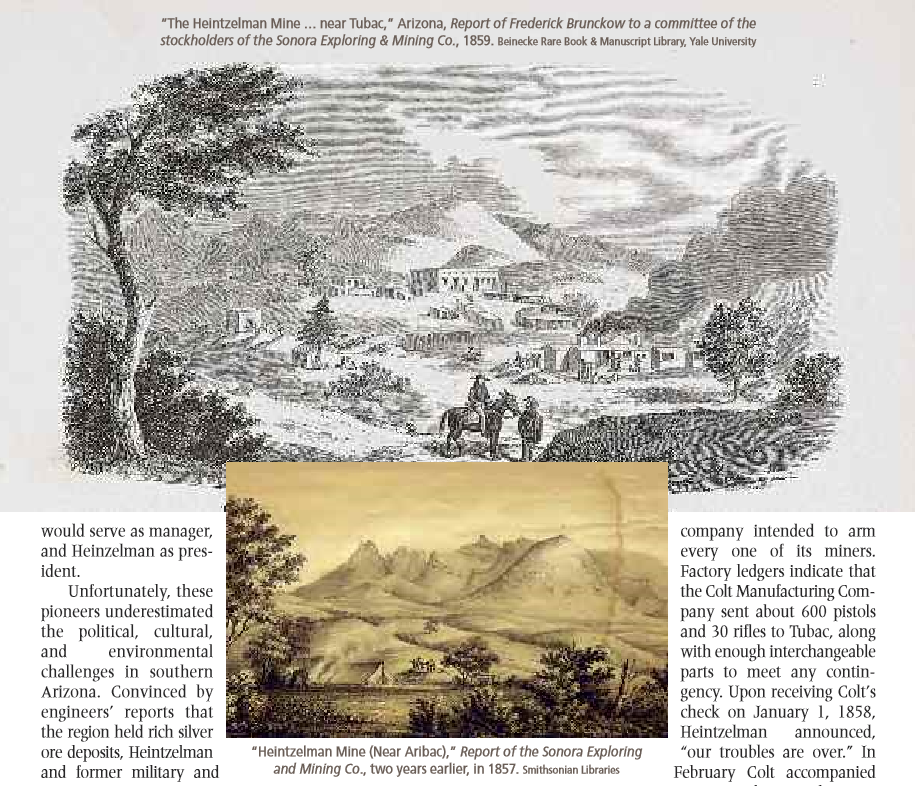

When Heintzelman arrived at the mine, he found it yielding far less ore than the company had anticipated. He blamed the labor force, but he appointed a highly skilled engineer, Frederick Brunckow, to supervise mining operations and left Arizona in January 1859. Once he reported problems with Indian attacks and thefts, Colt wanted all the miners and new settlers associated with the company “well armed,” enough to defend their properties.

Jarvis remained optimistic in his correspondence with his family about his prospects, despite Colt’s growing concern that the mine had become “a hole to bury money in.” Colt provided Jarvis with funds to invest in additional Sonoran properties, but Heintzelman’s somber assessment disturbed stockholders, aggravating tensions between Eastern and Midwestern board members. Family letters hint that an anxious Colt plotted to seize control of the company at the April 1859 stockholder’s meeting in Cincinnati, which he did by becoming its chief shareholder. Tubac’s Weekly ArizonianApril 21, 1859, recorded Colt as president, shipping magnate and New York investor William T. Coleman as vice president, and Richard Jarvis as treasurer. The company re-incorporated in New York after rejecting Connecticut as suspiciously beneficial to Colt’s personal interests, and because New York had more favorable joint stock laws.

Colt now enjoyed a board of directors he could trust to follow his vision and reassure stockholders. Heintzelman bitterly handed over the reins of the mining company to Colt, furious with Colt’s business tactics. Heintzelman recorded in his journal that Colt was “a most unreasonable man and one I don’t care to do business with.” Now free to operate by his own instincts and with his trusted associates and family in positions of influence, Colt looked to other financial ventures, such as selling munitions to Fort Buchanan.

Colt’s presidency raised his profile in Arizona. He promoted his brand name in the Weekly Arizonian, which his Cincinnati business partners, the Wrightson brothers, had begun publishing at Tubac in February 1859 to promote a railroad in Arizona. One issue lauded Colt’s self-made-man mystique, describing the manufacturing giant as having grown up “so poor that he mortgaged a lathe and other machinery to the Ames Manufacturing Company, to secure a debt of $750. Colt is now generally believed to be the richest man in Connecticut and he has the most complete armory for the manufacture of firearms in the world.”

Unfortunately, none of the steps to secure financial solvency resolved the mining company’s problems on the ground. Over the summer and spring of 1859 and into the Spring of the following year, the mines suffered more Indian attacks, likely the Apache. Colt shipped two steam engines and other machinery, worth about $27,000, hoping to keep the mines operating, but his director, chief engineer, and others expressed a desire to abandon the dangerous territory.

Colt’s private secretary, Jesse D. Alden (whom Colt had sent to relieve Jarvis at Tubac in September 1859), testified to the increasing dangers and risks in the region. Apache had raided the wagon station and ransacked the area, stealing muskets and supplies. “I was obliged to leave my bags at one of the stations and arrived here with no other clothing but what I had on my back,” he informed his employer. The lost items included gifts from Elizabeth Jarvis Colt to her brother, from whom Alden borrowed “a clean suit.” Jarvis’s father likely echoed the feelings of Colt and others, when he wrote, “It is a shame that the government keeps so little care of its people and possessions.”

Colt tried to keep abreast of day-to-day business. He instructed Alden to write as often as once per week, no matter how uneventful the week may have been—and he waived pleasantries. “My letters will probably be mostly about business,” he warned.

Colt maintained faith that mining and American ingenuity held the keys to Arizona’s promising future. In January 1860, Richard Jarvis wrote to Ohio congressman Thomas Corwin, on Colt’s behalf, explaining that “[t]he future of at least the Western portion of Arizona must depend upon the development of its mineral wealth.” He emphasized that the region most likely held a wealth of “precious, useful metals,” including gold, silver, and copper. This remained untapped because of the “difficulties and dangers” posed by “thieving and plundering bands of Apache.” Jarvis blamed Congress for not asserting the authority of law over the area. So long as southern Arizona was “a place of refuge for the vicious, and the outlawed of neighboring communities,” it would resist industrial development.

Arizonans also seemed to resist Colt’s products. The pace at which Arizonans had adopted Colt’s weapons disappointed and frustrated him. In a postscript to a February 1860 letter to his friend William M. B. Hartley, who managed the Colt Manufacturing Company’s New York office, Colt lamented: “I am noticing in the newspapers occasionally complimentary reference to the Sharp and Burnside rifles and carbines, anecdotes of them, of their use upon ‘grisley bares,’ Indians, Mexicans, and so fourth [sic]. This is all wrong. It should be Colt’s rifles, carbines, and so fourth. When there is or can be made a good story of the use of Colt revolving rifles, carbines, shot guns or pistols for publication in Arizona, the opportunity shouldn’t be lost.” He went on to request 100 copies of any such stories, promising to reward with a pistol or rifle any editor who published a favorable article. He also asked Hartley to encourage stories describing any accidents caused by his competitors’ guns, according to James L. Mitchell in Colt: the Man, the Arms, the Company (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole, 1959).

Meanwhile, conditions at the mines deteriorated rapidly. Chief engineer Frederick Brunckow reported continued Apache campaigns to steal workhorses and oxen. To maintain financial solvency, Colt began to sell or lease the company’s Arizona property to individual board members and other investors. In June 1860, the company’s board sent Andrew Talcott, originally of Glastonbury, Connecticut, to fill the position. Nevertheless, the volatile conditions persisted, igniting a worker rebellion that killed Brunckow and two other employees.

Meanwhile, conditions at the mines deteriorated rapidly. Chief engineer Frederick Brunckow reported continued Apache campaigns to steal workhorses and oxen. To maintain financial solvency, Colt began to sell or lease the company’s Arizona property to individual board members and other investors. In June 1860, the company’s board sent Andrew Talcott, originally of Glastonbury, Connecticut, to fill the position. Nevertheless, the volatile conditions persisted, igniting a worker rebellion that killed Brunckow and two other employees.

Before the company could regain footing, the Civil War forced the withdrawal of federal troops from Arizona in April 1861, and the company shut down its southern Arizona operations that summer. Consequently, Indian raiders and armed Mexicans crossed the border, compelling American civilians to flee the territory. Colt died of complications from gout on January 10, 1862, just as the Confederate Congress created its own Arizona Territory. When Confederate troops briefly occupied Tucson the following March, the U.S. Congress responded by also creating Arizona Territory, west of the 107th meridian, in February 1863, but it was too late to save the company. Hartley claimed that the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company had extracted $100,000 worth of silver from the Tubac mines, “but want of a Territorial Government, and military protection, from the thieving Apaches, as well as the lack of capital adequate to the effective working, and equipment of the mines have retarded the success….”

The Sonora Exploring and Mining Company ultimately failed to overcome the challenges of operating in a distant and unfamiliar land. Climate, isolation, inefficient management, Indian attacks, a national political crisis, unskilled labor, and Colt’s own health proved insurmountable obstacles. Nonetheless, Colt’s efforts to profit on his investment and create a market for his firearms in newly acquired American territory contributed to the political and economic infrastructure of what would eventually become Arizona.

Permanent Anglo settlement, supported by mining and agriculture, did not take firm root in the region until the 1870s when the imposition of American laws and governance, and the arrival of the railroad, eroded the political and economic power of Arizona’s Mexican community. Subsequent military campaigns against the Apaches profoundly changed the economic and political landscape, fostering American mining there for the next century. Colt firearms likely contributed to the success of those campaigns.

Leah Glaser is an associate professor of history and public history at Central Connecticut State University, where she teaches courses about the history of the American West.

LISTEN!

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 27: “Sam Colt Mines the Arizona Territory,” based on a lecture given at the Presidents College, University Of Hartford.