(c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2013

(c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2013

By Neil Hogan

The Irish were the first large group of immigrants to Connecticut (after the British and Dutch settlers). Though they began arriving in substantial numbers in the 1840s, their story actually begins in the colonial period. “In colonial records,” wrote Albert E. Van Dusen in his history of our state, Connecticut (Random House, 1961), “one finds Irish in small numbers scattered throughout all parts of Connecticut … A few Irish were transported to Connecticut as convicts or redemptioners. The latter, too poor to pay for passage, were required to serve a master here for a specified term of years …”

A letter written in 1653 by a Boston lawyer and merchant named Amos Richardson to a friend in Connecticut described an example of the redemptioner process. Richardson, who later became an early settler of Stonington, Connecticut, wrote that a ship carrying Irish servants had just arrived in Boston and that he had purchased the indentures of four of them—a husband and wife and two other women. “Those who have had tryall of Irish servants heare have found them to be good and so I hope these will prove,” he wrote.

By the time the Irish migration peaked in the 19th century, indentured servitude had died out. New arrivals found work for hire. Unlike with other ethnic groups, Irish women outnumbered Irish men. Domestic service became these women’s main occupation. In Seven Days a Week (Oxford University Press, 1978), David Katzman writes, “Irish-born women formed the largest single group within the foreign-born service class and it was this factor which gave rise to the image of the Irish domestic as the typical American servant.”

For wealthy and even moderately prosperous Connecticut families, these Irish women served as affordable labor for household tasks that New England working-class women had begun to spurn in favor of factory jobs. In Erin’s Daughters in America (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), Hasia R. Diner asserts, “Young American women basically refused to do this kind of work. Native-born Protestant girls in the nineteenth century found the notion of domestic work so odious, so demeaning, so beneath their sense of self that they in fact often took lower paid jobs in mills and in factories … rather than humiliate themselves in someone else’s homes …” But for Irish women, who arrived with few job skills and little money, domestic service was an opportunity to make it on their own in an adopted homeland.

In 1850, returns compiled by a Norwalk census taker who made a mistake revealed just how popular domestic service was among Irish immigrants. The census taker’s instructions that year were to list the occupation of men only. The Norwalk enumerator, however, also noted the occupations of about a quarter of the women. Of 213 female natives of Ireland living there, he listed 58 as having occupations: 57 were domestic servants and 1 was a home nurse. Evidence related to the living situations of other Irish-born women suggests others may have been working as domestics, but that can’t be confirmed.

At first, Irish women only slightly outnumbered men. The 1850 census showed 27,600 Irish natives in Connecticut, with the number of women exceeding the men by only 619. The number of Irish natives in Connecticut grew by leaps and bounds during the next 50 years, reaching a high of 71,500 in 1900. The gender gap widened, too: In 1900 there were 8,859 more Irish women than men.

In every city and town in Connecticut during that half century, large numbers of Irish women worked as domestic servants in all kinds of settings. In 1860, census records of the rural hamlet of Southbury (total population: 1,345), showed 12 Irish women employed as servants: 6 worked for farmers, 2 for widows, 2 for innkeepers, and 1 each for a lawyer and the Congregational minister. In 1870, the Russell Military Academy in the Wooster Square neighborhood of New Haven had five faculty members and 35 students from as far away as Mexico and Panama. They were waited on by an all-Irish and all-female domestic staff of six ranging in age from 27 to 40. A few houses away, wealthy hardware manufacturer Joseph Sargent had a similar household staff: waitress Rose Riley, 36, seamstress Julia Gibney, 25, cook Maggie Doyle, 23, nurse Hanna Kent, 40, with the addition of male coachman, George Doherty, 30.

In every city and town in Connecticut during that half century, large numbers of Irish women worked as domestic servants in all kinds of settings. In 1860, census records of the rural hamlet of Southbury (total population: 1,345), showed 12 Irish women employed as servants: 6 worked for farmers, 2 for widows, 2 for innkeepers, and 1 each for a lawyer and the Congregational minister. In 1870, the Russell Military Academy in the Wooster Square neighborhood of New Haven had five faculty members and 35 students from as far away as Mexico and Panama. They were waited on by an all-Irish and all-female domestic staff of six ranging in age from 27 to 40. A few houses away, wealthy hardware manufacturer Joseph Sargent had a similar household staff: waitress Rose Riley, 36, seamstress Julia Gibney, 25, cook Maggie Doyle, 23, nurse Hanna Kent, 40, with the addition of male coachman, George Doherty, 30.

By 1880, according to census records, there were 4,789 Irish-born women working as servants in Connecticut homes and institutions. By 1900, the number had grown to a peak of 5,571. In each case, almost half of these women were under age 25.

A 1936 Department of Labor survey of household employment in Hartford, Waterbury, and Litchfield found 1,151 women working as domestic servants in those communities, representing 22 nationalities. Irish women accounted for the largest percentage. The report said they “made up 14 percent of the Hartford workers, 12 percent in Waterbury and 28 percent in Litchfield.”

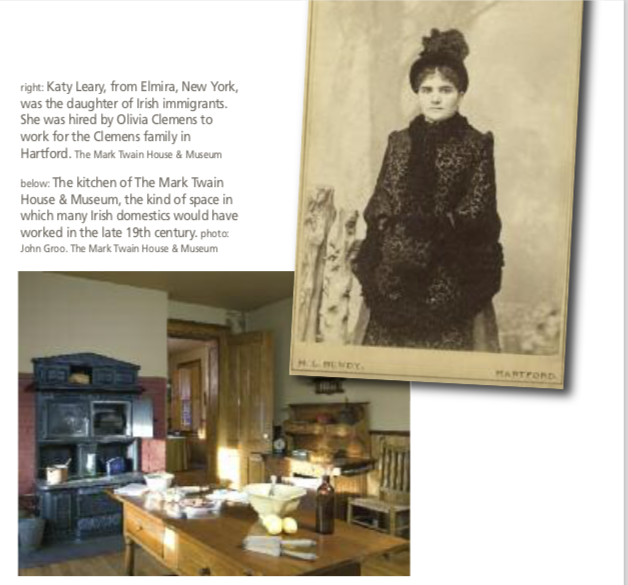

The survey also confirmed that domestic service was not easy. Work hours were long, averaging 10 hours a day and 60 to 70 hours per week. Hourly wages were lower than those for women in other occupations. Although the value of room and board increased the servant’s overall compensation, some servants lived in cellars or attics and had limited guest privileges. The duties of one middle-aged Hartford Irish woman who had been a domestic servant since she was a young girl included cooking, serving, cleaning, answering the phone, and helping to care for two children in a family of seven in a 16-room house.

Domestic work could be a tenuous existence. In 1847, two Irish servants in Lyme died in bed from fumes from a charcoal furnace, according to the Boston Pilot (February 6, 1847.) Bridget Hagan, 23, described in the New Haven Daily Palladium (June 11, 1852) as “a worthy and honest Irish girl,” died in that city when a camphene stove exploded in her employer’s home. (A highly volatile substance, camphene was sometimes used as a lamp fuel in the mid-19th century.) In 1853, Catherine Bohan, a servant in a Wallingford home, was charged with stealing money and a gold watch. Her 13-year-old accuser, Mary Rich, was the daughter of the tollgate keeper on the road between Wallingford and Durham. Rich said she learned while in a “magnetic and somnambulant state” that the Irish servant living in the home of a family named Parmalee was the thief. After deliberating for just 15 minutes, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty.

The fact that most Irish servants were Catholic and most New Englanders were Protestant exacerbated the natural tensions of living-in. According to Faye E. Dudden, in Serving Women: Household Service in Nineteenth Century America (Wesleyan University Press, 1983), some Protestants believed tracts that accused Catholic priests of instructing servants “to poison the food of their Protestant employers” and “to carry the small children of the family to them for secret baptism.” Some were afraid they were being spied on. One alarmed Protestant wrote in the Zion’s Herald and Wesleyan Journal (October 6, 1847): “Twelve years ago in the house which I boarded in this city there was a servant woman who … told my landlady that the priest made her tell what she had heard talked about in the house. … Many a rich family in Boston and all their private affairs are thus exposed to the Roman priesthood in this city by the Catholic servants they employ.”

In Lakeville, Connecticut in 1883, the fate of female Irish servants became a bargaining chip in a sectarian dispute over various religious, political, and educational issues. When a Catholic pastor urged a boycott of Protestant storeowners, Protestant women threatened to fire all their Irish servants, reported the New Haven Register (October 10, 1883). Fortunately, tempers on both sides cooled before words became actions.

Irish servants also came under criticism for more practical failings. In their 1869 book American Woman’s Home, Hartford’s Catharine Beecher and her sister Harriet Beecher Stowe (of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame) complained about Irish servants’ “toiling from daylight to sunset” to finish chores that a New England girl would complete before noon. They described Irish servants as displaying “all the unreasoning heats and prejudices of the Celtic blood …” and portrayed them as slovenly, uncultivated, disrespectful, and overbearing. Still, on another occasion, Stowe conceded there were mitigating circumstances: “Considering their youth, their inexperience, their coming strangers into the country, their separation from parental oversight—their uniform purity and propriety is certainly remarkable.”

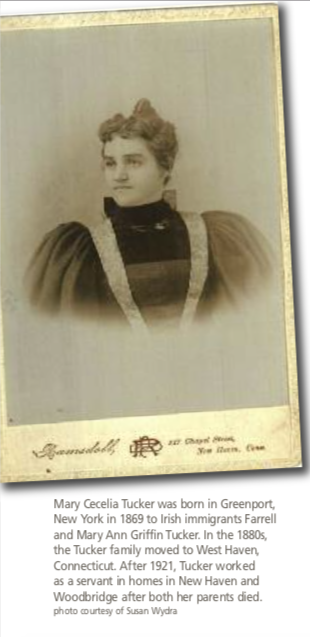

The Irish women who came to the United States to work as servants were of peasant stock and had grown up in one- or two-room cottages. Though they lacked polish and sophistication, they hardly deserved the harsh stereotype pinned upon them. In fact, not a few of them sparkled. When Mark Twain’s wife Olivia Clemens added a young Irish-American servant from Elmira, New York, to the domestic staff in Hartford, Twain was skeptical, according to another Twain servant, Mary Lawton. In her memoir A Lifetime With Mark Twain (Harcourt, Brace, 1925), Lawton quotes Twain’s response: “So you hired that girl. … Well did you notice them wide, thick black eyebrows of hers? … She’s got a terrible fierce temper, I believe. Nothing halfway about her. Yes, I think you’ll find she has a temper. She’s Irish.”

But “that girl,” Katy Leary, eventually won the hearts of the entire Clemens family, so much so that she became, according to Lawton’s book, the only person other than Olivia who was allowed to dust and tidy up the desk where Twain did his writing. Lawton also wrote that Leary’s “quaint sayings and philosophies and funny stories of the family happenings bubbled up like the Fountain of Life, and were an unfailing source of delight to all who heard them … The Irish wit of her, the Irish quickness of her, the Irish deftness of her and sometimes when necessary the Irish blarney of her was something to think over, something to laugh over and something sometimes to weep over.”

But “that girl,” Katy Leary, eventually won the hearts of the entire Clemens family, so much so that she became, according to Lawton’s book, the only person other than Olivia who was allowed to dust and tidy up the desk where Twain did his writing. Lawton also wrote that Leary’s “quaint sayings and philosophies and funny stories of the family happenings bubbled up like the Fountain of Life, and were an unfailing source of delight to all who heard them … The Irish wit of her, the Irish quickness of her, the Irish deftness of her and sometimes when necessary the Irish blarney of her was something to think over, something to laugh over and something sometimes to weep over.”

Another sparkling domestic servant was Maggie Maher, a Tipperary girl, who in the 1860s became the prize in a tug-of-war between two prominent New England families: the Dickinsons of Amherst, Massachusetts, whose daughter was the famous poet Emily, and the Boltwoods of Hartford. When Maher decided to leave the Boltwoods and return to the Dickinsons so she could be nearer her own sister, she set off a tempest of alternating charges, curses, offers, and threats, according to Daniel E. Sutherland in Americans and Their Servants (Louisiana State University Press, 1981). In the end, she remained with the Dickinsons.

Testimony from Irish domestics themselves is rare, but the diary of Mary McKeon of Cashcarrigan, County Leitrim, has survived to provide a fascinating first-person account of domestic service. McKeon was just 16 in 1883 when she was greeted in New Haven by an aunt and uncle and went to work for a family named Osborn. Her diary entries describe the daily routine: “I came downstairs at 6 and swept my walk before breakfast. … I washed the paint [and]I cleaned silver this forenoon. … I brushed the window blinds. … I had to fold my clothes and sweep my walk, set my table and bring water before breakfast. … I had to work very hard this forenoon. … I had to wait for dinner, we had 6 courses, the last was strawberries and ice cream. …”

McKeon spent her leisure time with other Irish servants: Mary McWeeney on Grove Street, Maggie Lyons on Dwight Street, and Mary Mooney of Savin Rock. She tells about their meeting at church on Sunday mornings and strolling downtown of an evening to shop and socialize. McKeon confided how much she missed her home and family. “It’s a lovely day. I’m just thinking of home and this day 3 years, I was newly landed in America,” she wrote, adding, “I’m homesick and discontented. … I’ve been dreaming of Dan and my Uncle Tim and home these last three nights.”

The longing for home was common. Englishwoman Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley wrote in her book Travels in the United States, Etc. during 1849 and 1850 (Harper & Brothers, 1851) of an encounter she had with a servant in Bridgeport while touring America in October 1849. “Here was a poor Irish housemaid … who touched our feelings extremely,” she wrote. “When she came in with our tea. … she seemed delighted to talk about the ’ould country, ill off as she had been there. She seemed to think it the most beauteous and charming place on the face of the globe. …”

One Irish servant in the 1930s found the town of Litchfield to be an antidote for her homesickness. “A family by the name of Green was looking for someone to go to Litchfield for the summer,” wrote Elizabeth Knox in her Autobiography of Elizabeth Mary Doherty Knox (unpublished, collection of the Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society). “I took the job right away. … Litchfield was like Ireland at that time of year… everything springing to life,” wrote Knox, a native of Tournafulla, County Limerick. Pastoral Litchfield did more for Elizabeth than remind her of Ireland. She wrote that her morning duties included picking up milk at a nearby farm. She often had to do the milking herself, as most Irish girls could. In the process, she got to know the farmer’s son, and she eventually became his wife.

As much as longing for their families and homeland tugged at their heartstrings, servants found satisfaction in the opportunities available to them in America. An oral history interview by Elizabeth M. Buckingham in Bridgeport on October 6, 1939 (Works Progress Administration, Bridgeport Historical Society, Bridgeport Public Library) provides another Irish servant’s experience. Identified only as “Mrs. G.,” she was born in Strokestown, County Roscommon, and left Ireland around 1907 thanks to a cousin who paid her fare. She worked as a cook for a New York City family and later became a pastry maker in the home of an unidentified wealthy Bridgeport family. Mrs. G. said the Irish staff there included two cooks, two waitresses, and two chambermaids; the lady of the house was pleased with the arrangement, saying that girls who knew each other would be more contented and more satisfactory. Mrs. G. said her $65-a-month salary not only covered expenses but left enough for her to send money home to Ireland to help her family. After five years, she left domestic service and married a fellow Irish immigrant who worked on Bridgeport’s trolley cars. Her employer gave her “a wedding present of my bedroom, living room and kitchen stove and her husband gave me $50.”

Ellen O’Neill was an Irish immigrant who found both a suitable workplace and a sort of home away from home. Nellie, as she was known, arrived at Ellis Island in May 1897 from Sneem, County Kerry, with three brothers. Her brothers became coachmen and gardeners. She was hired as a cook and housekeeper at 71 Williams Street, Norwich, the upscale home of two professional women, Christiana Faunce, a physician, and Helen Marshall, a high-school Latin teacher. Nellie’s grandson, Paul Keroack, says that O’Neill family tradition has it that her employers treated Nellie like a daughter. When Nellie left to marry after seven years, Faunce and Marshall gave her a set of fine china. Keroack treasures two of his grandmother’s belongings: the cookbook Nellie used in the kitchen of her employers and a greeting card given Nellie upon her departure bearing the inscription, “The latch string is always out at 71 Williams Street.”

Another Irish woman who recalls a happy end to her tenure as a domestic servant is Mary Moran Waldron of Hamden, who at the age of 102 is probably the oldest former domestic servant in Connecticut. According to her son George Waldron, president of the Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society, Mary arrived in New Haven in 1928 at age 17 from Ballyhaunis, County Mayo. Her son says Waldron found work and developed lifetime friendships with two families, the Vogals and the Bogarts. Like many other servants, she was able to save enough money to pay the passage of a relative: her sister Delia Moran also worked as a housemaid after arriving in America. Moran later married John O’Brien and had two children. Mary and her husband David Waldron, also a native of Ballyhaunis, had eight children. Mary’s son says that she still reminisces about her days as a servant.

In hopes of documenting more fully the experiences of Irish immigrant women in Connecticut who worked as domestic servants, the Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society is collecting reminiscences about them for the society’s library and possibly for publication of a book or audio-visual presentation. The 81-page diary of Mary McKeon is being transcribed by a Sacred Heart University student; the transcript will be made available to the public. Anyone with documents or stories about Connecticut Irish domestic servants is invited to contact the society: 203-392-6435 or ctiahs@gmail.com.

Neil Hogan is editor of the Connecticut Irish-American Historical Society’s quarterly newsletter The Shanachie.

Explore!

The Connecticut Irish American Historical Society

Ethnic Heritage Center

270 Fitch Street

New Haven

For more information visit ctiahs.com or call 203-392-6126.