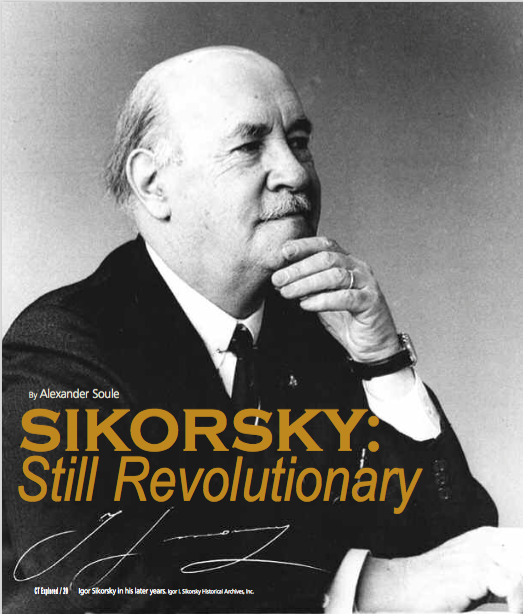

By Alexander Soule

By Alexander Soule

(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2014

Subscribe to receive every issue!

It was not an auspicious beginning. At the crack of dawn of September 21, 1926, 37-year-old Igor I. Sikorsky stood on a low hill on Long Island overlooking the thousands of people who crowded a narrow runway below. A biplane emblazoned with his own name had a French World War I ace at the controls and carried more than 2,500 gallons of gas as it attempted to take off on a 3,600-mile flight to Paris.

The weight of the fuel the craft was carrying collapsed the landing gear of the Sikorsky S-35, causing it to careen over an embankment at the end of the runway. The pilot and copilot managed to escape the ensuing fireball, but the two other crewmembers perished.

At stake that grim morning was the very survival of the Sikorsky Manufacturing Corporation, founded in 1923 as the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation and now leveraged to the hilt in the now-charred hulk of the smoldering S-35. “The financial situation of the company was obviously deplorable,” Sikorsky recalled in his autobiography The Story of the Winged-S (Dodd, Mead & Co., 1938). “At that time there was no possibility of insuring the ship and it was a total loss, the major part of which fell on our organization. All our capital was spent, and in addition there was an indebtedness many times in excess of our assets. Sikorsky, however, succeeded in scraping together enough cash to start work on a new plane. Within two years, Sikorsky had built an amphibious aircraft (one that could take off and land on water), and his fortunes turned a corner. The aircraft’s performance would secure Sikorsky a U.S. Navy contract and a deal with Pan American Airways.

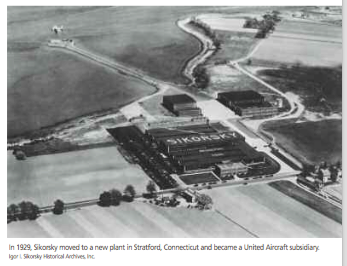

In 1929, with more business than his Long Island site could handle, Sikorsky accepted a $5-million buyout from the Hartford-based United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, which had just formed from the combination of Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, Hamilton Standard Propeller, and Chance Vought. “At the time there were other alternatives but my associates and I were strongly in favor of United Aircraft Corporation, because we felt that this fine, progressive and substantial organization which combined engine, propeller and aircraft manufacturers and at that time even airline operation, were a group which would permit us to develop to the best extent our inherent possibilities,” Sikorsky explained in The Story of the Winged-S.

Stratford was chosen as the site for a new Sikorsky factory, both because of the new airport under construction nearby and its waterfront location on Long Island Sound, providing the company both runway and waterway takeoff capabilities.

Stratford was chosen as the site for a new Sikorsky factory, both because of the new airport under construction nearby and its waterfront location on Long Island Sound, providing the company both runway and waterway takeoff capabilities.

In July 1929, the new plant was ready for its tenant. “An excellent, modern aircraft factory, with first-class machinery, equipment, offices, drafting rooms, research laboratories and a wind tunnel, was planned and … erected,” Sikorsky wrote. As United Aircraft president Eugene Wilson later recalled it, Sikorsky was soon running “the strangest factory on earth,” its plant floor crowded with Russian immigrants. Sikorsky had originally launched his airplane company with encouragement and financial backing from fellow Russian immigrants in New York City, having eventually landed there after fleeing the chaos of the Russian Revolution. Born May 25, 1889 in Kiev, he had honed both his craft and his reputation in Russia building the first-ever multi-engine plane, which would evolve into land-based bombers that saw action in World War I.

The amphibious Sikorsky-built Pan Am Clippers became an icon at the outset of transoceanic flight, but Sikorsky did not foresee the short-lived era of the flying boat. Airports soon sprouted to accommodate larger, land-based planes. It was a strategic blunder deftly sidestepped by Sikorsky’s former United Aircraft peer Boeing, which had been spun back out as an independent company in the Air Mail Act of 1934. Boeing produced a dozen big Pan Am Clippers, but it also built on its experience building cross-country mail carriers to create the first all-metal passenger airliner in 1933, and in 1938, the first airliner with a pressurized cabin. Douglas Aircraft, meanwhile, won a contract in 1932 to build a fleet of DC-1 passenger airplanes for TWA (then the Transcontinental and Western Air, Inc., later named Trans World Airlines). With the California company progressing in 1936 to the iconic DC-3, the writing was on the wall for Sikorsky’s flying boats.

The amphibious Sikorsky-built Pan Am Clippers became an icon at the outset of transoceanic flight, but Sikorsky did not foresee the short-lived era of the flying boat. Airports soon sprouted to accommodate larger, land-based planes. It was a strategic blunder deftly sidestepped by Sikorsky’s former United Aircraft peer Boeing, which had been spun back out as an independent company in the Air Mail Act of 1934. Boeing produced a dozen big Pan Am Clippers, but it also built on its experience building cross-country mail carriers to create the first all-metal passenger airliner in 1933, and in 1938, the first airliner with a pressurized cabin. Douglas Aircraft, meanwhile, won a contract in 1932 to build a fleet of DC-1 passenger airplanes for TWA (then the Transcontinental and Western Air, Inc., later named Trans World Airlines). With the California company progressing in 1936 to the iconic DC-3, the writing was on the wall for Sikorsky’s flying boats.

“The trouble was that, when he proved that his flying boats could cross the oceans safely in one jump, he paved the way for their replacement by land planes,” Wilson wrote in a 1956 Reader’s Digest article about Sikorsky. “By 1938 we had a factory full of wonderful people, but no orders. Several factors saved Sikorsky from the speedy demise of the flying clipper: Nazi Germany’s 1939 invasion of Poland, which put United Aircraft and other U.S. manufacturers on a war footing, and Sikorsky’s longtime fascination with the possibilities of vertical lift. As a child he’d experimented with rubber-band helicopters, and in 1909 and 1910 he attempted the real thing with two helicopters that never got off the ground.

Sikorsky had two more things going for him: a patron in United Aircraft’s Wilson, who had a war chest bursting with excess cash and a willingness to bet on an unproven technology, and a made-to-order engineering shop with proven success solving knotty aeronautical problems and converting theory to working prototypes.

In 1939, airplane production dominated the attention of Wilson and his cohorts at United Aircraft, which moved its Chance Vought airplane manufacturing division to Sikorsky’s Stratford plant. During the war years, the U.S. government ordered 10,000 F4U-Corsair fighters, overwhelming the production capabilities of the rechristened Vought-Sikorsky facilities in Stratford. (Other companies took up the slack at other sites.) Vought-Sikorsky employed more than 12,000 people at the peak of the war years, making it among the largest manufacturing sites in New England.

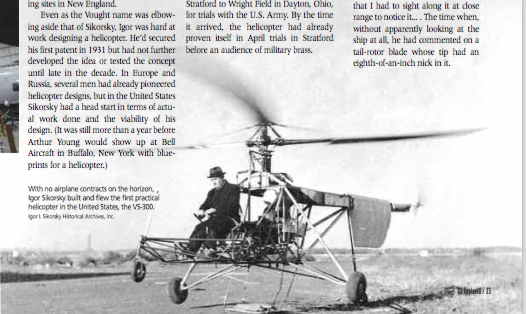

Even as the Vought name was elbowing aside that of Sikorsky, Igor was hard at work designing a helicopter. He’d secured his first patent in 1931 but had not further developed the idea or tested the concept until late in the decade. In Europe and Russia, several men had already pioneered helicopter designs, but in the United States Sikorsky had a head start in terms of actual work done and the viability of his design. (It was still more than a year before Arthur Young would show up at Bell Aircraft in Buffalo, New York with blueprints for a helicopter.)

Even as the Vought name was elbowing aside that of Sikorsky, Igor was hard at work designing a helicopter. He’d secured his first patent in 1931 but had not further developed the idea or tested the concept until late in the decade. In Europe and Russia, several men had already pioneered helicopter designs, but in the United States Sikorsky had a head start in terms of actual work done and the viability of his design. (It was still more than a year before Arthur Young would show up at Bell Aircraft in Buffalo, New York with blueprints for a helicopter.)

Helicopter design entails addressing six major factors, according to J. Gordon Leishman, professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Maryland: weight, engine power, rotor torque, vibration, stability, and the basic theories of lift as applied to rotors. Sikorsky’s resulting VS-300, a Tinker Toy-like contraption that underwent so many rebuilds workers called it “Igor’s nightmare,” suffered from extreme vibration on its first flight on September 14, 1939. That year, wearing his trademark fedora hat and seated in an open cockpit, Sikorsky managed short “hops” of up to a few minutes’ duration with lines tethering the aircraft to the ground. In May 1940, the VS-300 took its first untethered flight, and the following January, the U.S. Army signed a contract for Sikorsky to build the R-4 Hoverfly helicopter.

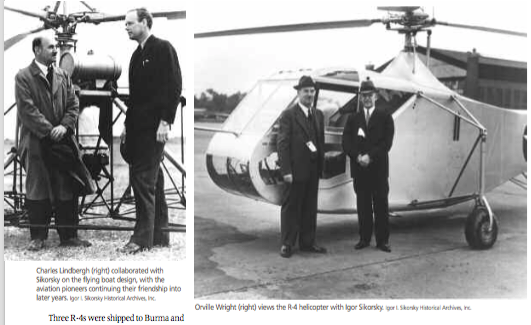

Over six days in mid-May 1942, a pilot flew the R-4 more than 750 miles from Stratford to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, for trials with the U.S. Army. By the time it arrived, the helicopter had already proven itself in April trials in Stratford before an audience of military brass. As chronicled by the Stratford-based Igor I. Sikorsky Historical Archives, those trials included the pilot’s spearing a 10-inch ring using a projecting tube and “handing” the ring to Igor Sikorsky while hovering. In another demonstration, the pilot maneuvered the helicopter to lower a bag of eggs suspended from a rope to the ground, keeping the shells intact.

Pilot Charles “Les” Morris recalled the event in a memoir published by the Sikorsky Archives, providing a glimpse of his boss’s penchant for engineering detail. Mr. Sikorsky hovered near, nervously chewing at the corner of his mouth. His keen gray-blue eyes flashed out from under the familiar gray fedora as they searched every detail of the craft to detect any sign of flaw. I knew the capacity of those eyes from experience—that time they had seen from twenty-five feet the strut that was so slightly bent that I had to sight along it at close range to notice it … The time when, without apparently looking at the ship at all, he had commented on a tail-rotor blade whose tip had an eighth of-an-inch nick in it.

Pilot Charles “Les” Morris recalled the event in a memoir published by the Sikorsky Archives, providing a glimpse of his boss’s penchant for engineering detail. Mr. Sikorsky hovered near, nervously chewing at the corner of his mouth. His keen gray-blue eyes flashed out from under the familiar gray fedora as they searched every detail of the craft to detect any sign of flaw. I knew the capacity of those eyes from experience—that time they had seen from twenty-five feet the strut that was so slightly bent that I had to sight along it at close range to notice it … The time when, without apparently looking at the ship at all, he had commented on a tail-rotor blade whose tip had an eighth of-an-inch nick in it.

Three R-4s were shipped to Burma and were used in April 1944 in a combat theater for the first time to rescue occupants of a medical evacuation plane that had crashed in enemy territory. “It felt, you know, that I was part of the whole sequence of events, with Sikorsky thinking, ‘This is a good machine for rescuing people,’” said pilot Carter Harman. “I went ahead and I showed it could be done on his machine.” Sikorsky’s nephew Dmitry “Jimmy” Viner made history on November 29, 1945 with the first use of a helicopter to hoist people from peril, hovering a Sikorsky R-5 helicopter to pluck two crewmembers from an oil barge snagged on Penfield Reef off Fairfield during a storm.

Helicopters were used in isolated instances during World War II, but they played a major role in the Korean War in the early 1950s. The spindly, bubble-canopied Bell H-13 Sioux is the most recognizable helicopter from period—thanks to its prominent role in the opening credits of the war sitcom M*A*S*H. But the Sikorsky H-19 Chickasaw (the S-55 in Sikorsky’s aircraft lineage) performed yeoman’s work evacuating wounded soldiers, ferrying troops and cargo, and performing rescues, among other utility missions.

The U.S. government ordered more than 1,000 Chickasaw helicopters. This was comeback of sorts for Sikorsky, after earlier attempts to build larger helicopters from smaller models failed due to design flaws affecting stability and control. “After losing those contracts Sikorsky was practically out of business,” said Dan Libertino, executive director of Sikorsky Archives. “Then they came up with the S-55…. That became the utility helicopter of choice.In 1952, two S-55 variants became the first helicopters to cross the Atlantic, hopscotching from Maine to Iceland and then Scotland. The company sold thousands more successor helicopters that traced their engineering inspiration to the S-55.

The U.S. government ordered more than 1,000 Chickasaw helicopters. This was comeback of sorts for Sikorsky, after earlier attempts to build larger helicopters from smaller models failed due to design flaws affecting stability and control. “After losing those contracts Sikorsky was practically out of business,” said Dan Libertino, executive director of Sikorsky Archives. “Then they came up with the S-55…. That became the utility helicopter of choice.In 1952, two S-55 variants became the first helicopters to cross the Atlantic, hopscotching from Maine to Iceland and then Scotland. The company sold thousands more successor helicopters that traced their engineering inspiration to the S-55.

With military manufacturing straining a Bridgeport facility into which Sikorsky had expanded in 1943, Sikorsky was forced to license production for 900 R-6 helicopters to a Michigan company, chosen in part for its previous experience producing aircraft engines and propeller blades under license from United Aircraft subsidiaries Pratt & Whitney and Hamilton Sundstrand. By 1955, Sikorsky Aircraft solved its capacity problem by relocating its facility further up the Housatonic River.

Today, that headquarters is the largest single manufacturing plant in Connecticut, having employed more than 9,000 people at the height of the U.S. war in Afghanistan. Between 1955 and today, Sikorsky’s fortunes have hewed closely to its successes and failures in landing U.S. military contracts. The company has vied with Bell, Boeing, and predecessor companies for U.S. Army and Navy contracts while still trying to drum up interest from commercial customers and international militaries.

In 1960, as the United States inched toward greater involvement in the Vietnam War, rival Bell Helicopter beat out Sikorsky for an all-purpose, turbine-engine helicopter, despite the fact that Sikorsky’s XH-39 had set helicopter altitude and speed records at Bridgeport and at Bradley Field in Windsor Locks. With full production beginning in 1960, Bell’s UH-1 Iroquois “Huey” would become the most-manufactured helicopter in U.S. history, with more than 16,000 units produced.

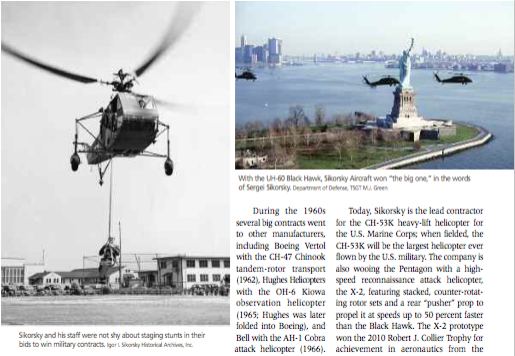

During the 1960s several big contracts went to other manufacturers, including Boeing Vertol with the CH-47 Chinook tandem-rotor transport (1962), Hughes Helicopters with the OH-6 Kiowa observation helicopter (1965; Hughes was later folded into Boeing), and Bell with the AH-1 Cobra attack helicopter (1966). Sikorsky, however, won the most prized contract of them all. In 1974 the company beat out fellow finalist Boeing to produce the U.S. Army’s next utility helicopter, and the UH-60 Black Hawk entered service in 1979. According to the Sikorsky Archives, the company is approaching 4,000 Black Hawk and derivative aircraft built—and counting. “Let’s put it this way. When the contract was first publicized, the aircraft industry in America knew that this was the big one,” said son Sergei Sikorsky in my interview with him in October 2013. “Whoever won this one would probably dominate the helicopter scene.” Sergei’s father did not live to see that day. Igor Sikorsky died on October 26, 1972, at age 83.

Today, Sikorsky is the lead contractor for the CH-53K heavy-lift helicopter for the U.S. Marine Corps; when fielded, the CH-53K will be the largest helicopter ever flown by the U.S. military. The company is also wooing the Pentagon with a high-speed reconnaissance attack helicopter, the X-2, featuring stacked, counter-rotating rotor sets and a rear “pusher” prop to propel it at speeds up to 50 percent faster than the Black Hawk. The X-2 prototype won the 2010 Robert J. Collier Trophy for achievement in aeronautics from the National Aeronautic Association, the highest accolade in the U.S. industry.

More than 85 years since Igor Sikorsky left Long Island to set up shop in Connecticut, his company remains revolutionary. “After the Wright brothers, I think his contributions to the development of aviation were the most important in the world,” said Michael Speciale, executive director of the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks. There you can see several Sikorsky airplanes and helicopters and learn more about the pioneering Igor Sikorsky. Alexander Soule is an independent writer and Redding resident.

More than 85 years since Igor Sikorsky left Long Island to set up shop in Connecticut, his company remains revolutionary. “After the Wright brothers, I think his contributions to the development of aviation were the most important in the world,” said Michael Speciale, executive director of the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks. There you can see several Sikorsky airplanes and helicopters and learn more about the pioneering Igor Sikorsky. Alexander Soule is an independent writer and Redding resident.

Explore!

The New England Air Museum 36 Perimeter Road, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks neam.org; 860-623-3305