A Legacy of Nonviolence in Voluntown

A Legacy of Nonviolence in Voluntown

By Michael Centore

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Voluntown is an out-of-the-way place, tucked away in the northeast corner of New London County on the Rhode Island border. Its population of just over 2,500 makes it one of the smallest communities in the state. Like the other towns of the Last Green Valley National Heritage Corridor, it is an oasis of calm amidst the Northeast’s belt of urban sprawl.

Despite its remoteness, Voluntown found itself at the center of a national news story 50 years ago. The August 26, 1968, edition of the Las Vegas Sunreported: “State police maintained an armed guard yesterday at a Pacifist camp [in Voluntown]where a dozen [sic] heavily armed members of the . . . Minutemen staged a pre-dawn raid earlier this weekend. A force of 50 state police, warned by the FBI of the planned raid, arrested all six Minutemen early Saturday after a gun battle in which four Minutemen, a trooper and a woman resident of the camp were wounded.”

The story seemed to raise more questions than answers. What was this “pacifist camp”? Who were the Minutemen? Why did the situation turn so violent? It appeared that the unrest of that tumultuous year, which saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, had spread to even the quietest corners of the country.

The Origins of Polaris Action

Born in 1927 to a Unitarian minister father and a pacifist mother in Chicago, Bradford Lyttle was steeped in the language of nonviolence from an early age. In 1957 he joined Non-Violent Action Against Nuclear Weapons, led by Chicago Quaker Lawrence Scott. That August the group went to Las Vegas to demonstrate against U.S. testing of atomic bombs. Other demonstrations followed in 1958, including a run-in with the U.S. Coast Guard when the group attempted to sail a boat, the Golden Rule, into U.S. nuclear testing grounds in the Marshall Islands in February.

The group reorganized itself as the Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) in September. Lyttle was instrumental in organizing the CNVA-sponsored Omaha Action project, a protest against a ballistic-missile construction site in Mead, Nebraska. Along with several others, he was arrested for trespassing and sentenced to six months in federal prison in Missouri.

Lyttle was an inveterate reader with a master’s degree in English literature and spent much of his time in the prison library. There he saw an ad in a magazine for Polaris submarines built at General Dynamics in New London. He thought this might be an ideal place for a demonstration, considering Connecticut’s proximity to the mass media outlets of New York City. Upon his release in 1960 he came east to begin work on the CNVA’s Polaris Action project.

Among the CNVA associates who joined him in Connecticut were Robert (“Bob”) and Marjorie Swann. The Swanns were parents of four young children and active in pacifist circles. Marjorie had participated in Omaha Action and, like Lyttle, had been arrested for trespassing. She too had been sentenced to six months in jail.

Swann’s experience at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, made her a more devoted and circumspect activist. “For the ‘prisoner of conscience,’” she later wrote in an essay in Free Radicals: War Resisters in Prison(Trine Day, 2017), “prison can be a positive experience which adds depth to one’s commitment to brotherhood and peace.”

She and Bob, along with Lyttle and other collaborators, threw themselves into a “round-the-clock” Polaris Action project. In Decade of Nonviolence: Through the Years with New England CNVA(New England CNVA, 1970), she described the project as being “concentrated on educating Americans to the realities and dangers of the nuclear deterrent policy typified by the Polaris submarines and their deadly cargoes of nuclear missiles.” The group set up an office near the General Dynamics Electric Boat shipyard, distributed leaflets to workers, held daily vigils, and sailed out into the Thames River in attempt to board the submarines.

The Swanns founded the first CNVA “community house” in Norwich. About 10 to 15 people lived there while actions were happening at the New London base. The group lived frugally and depended largely on charitable donations.

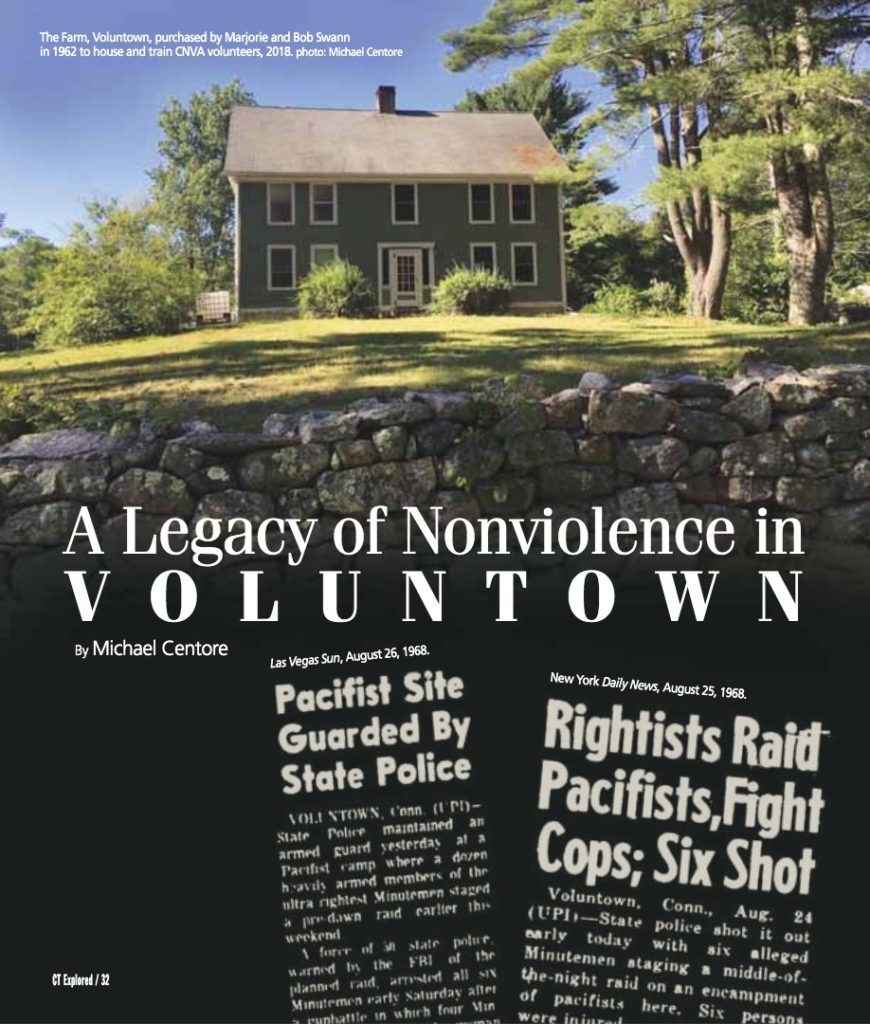

They experienced pushback from the local community. The Polaris Action office was vandalized on more than one occasion. The group remained, even developing a “shipyard conversion campaign” that outlined ways Electric Boat could transition from munitions production into desalination technology, but they began to think about finding a new base of operations. The Swanns realized they wanted to be in a more rural setting where they could foster community and develop connections to nature and ecological living. In 1962 they found the ideal location in an 18th-century farmhouse on a 40-acre parcel of land in Voluntown.

Moving to Voluntown

Barbara Deming was a 43-year-old reporter for the Nationwhen she attended a seminar on nonviolence in New London in August 1960. Members of the CNVA impressed her with their sense of purpose, and she decided to stay and work with Polaris Action. In 1962 Deming’s partner, the painter Mary Meigs, helped the Swanns financially to purchase the Voluntown farmhouse. Their intention was to use it as a headquarters for a New England branch of the CNVA. “The Farm,” as it came to be known, was close enough to Electric Boat that the group could continue Polaris Action.

Soon activists were traveling from the CNVA’s national headquarters at 5 Beekman Street in New York City to Voluntown to participate in events, establishing a dialogue between the two communities. The Farm became something of a rural outpost for the pacifist movement; the primary focus was on anti-war efforts, but residents began branching out into organic gardening and other environmentally sustainable practices.

In his autobiography, Peace, Civil Rights, and the Search for Community(Schumacher Center for New Economics, 1998), Bob Swann wrote of the Farm, “Our entire budget for all living expenses including food, transport, utilities, etc., was around $20,000 per year. We raised all this money from our New England mailing list. No one received a salary for working with CNVA, and all expenses came out of the same pot.”

The Swanns’ daughter Carol, who lived in Voluntown with her parents and three siblings, explained to me the ethos of the Farm: “Some people get impressions that it was a commune. But it was not a commune. CNVA was a seminal center for the training of nonviolence and political direct action in its time. There were anywhere from 10 to 50 people of various genders, races, sexual identities, and ages, studying, training, gardening, and taking action. Gandhi’s principles of living simply, consuming less, sharing finances for economic equity, and creating alternative structures to replace oppressive ones were all a part of CNVA’s mission.”

The Swanns became mentors to many of the younger visitors. “Their interest was in being effective social activists and organizers,” Carol says of her parents. C.J. Hinke was a young activist from New York when he began traveling to the Farm to work on Polaris Action. “There were core duties to be performed,” he wrote to me in an e-mail, “but mostly we each decided where we would be most effective. We alternated activist work with the physical chores a farm requires.”

Some local residents viewed the Farm with suspicion. Sociopolitical tensions were mounting across America, and Voluntown was no exception. In 1966 their fears boiled over into outright hostility when arsonists torched a barn on the property close to the house. Firemen arrived too late to put out the blaze. It was a frightening prelude of what was to come.

Threats and Surveillance

Founded in the early 1960s in Missouri by Robert Bolivar Depugh, a chemist and entrepreneur specializing in veterinary pharmaceuticals, the Minutemen were a fervent anti-communist organization with ties to the John Birch Society. Depugh was a former “Bircher,” and the conspiratorial thinking of that group informed his new band of vigilantes. Though ostensibly based in Missouri, Depugh’s home state, the organization had cells across the country.

In October 1966 police in Queens, New York, arrested 24 Minutemen and seized a massive amount of weapons and ammunition, including 125 rifles, a bazooka, and 3 grenade launchers. Police alleged that the Minutemen were plotting to attack three camps in the tri-state area that the Minutemen believed had communist sympathies, including CNVA headquarters in Voluntown.

Depugh was sentenced in January 1967 to four years in prison for violations of the National Firearms Act. In his 1968 book about the group, The Minutemen, reporter J. Harry Jones contends that “from that day forth . . . the Minutemen rhetoric became yet more violent and now was coated with a sense of immediacy and fear that had been less pronounced until then.”

This is the environment Jerry Elmer, then a 17-year-old antiwar activist, encountered on his first visit to the Farm in 1968. “On the bulletin board in the dining room was a threatening letter from a right-wing paramilitary group that called itself the Minutemen,” he writes in his memoir Felon for Peace(Vanderbilt University Press, 2005). “The letter had been sent to many peace groups; it showed the crosshairs of a rifle and bore the words: ‘Beware! Even now the crosshairs are at the back of your head!’” Hinke informed me of a similar experience: “Birchers and even the Klan made a lot of printed threats [to the CNVA],” he said, “but we never took them seriously.”

A few days after Elmer’s arrival in mid-August, Catholic missionaries Tom and Marjorie Melville gave a presentation at the CNVA about their work in Guatemala. CNVA residents noticed three unfamiliar men at the meeting who appeared to have been drinking. Later the three men followed residents back to the main house for a brief, if combative, discussion. They looked around the first floor before leaving abruptly.

Both the Minutemen and the CNVA were known to be monitored by law-enforcement agencies. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover spoke of an ongoing investigation of the Minutemen when he testified before the House Appropriations Subcommittee in 1965. Lyttle believes that the Connecticut state police began to observe the CNVA more closely after the barn burning of 1966. “They did not want pacifists killed on their watch,” he told me, citing the political consequences of such a tragedy. Hinke stated plainly, “All peace organizations were considered infiltrated. Government couldn’t tell the difference between pacifists and Maoists.”

The Attack

Ever since the barn burning, CNVA residents had maintained a nightly watch. At 2:30 a.m. on August 24, 1968, Mary Suzuki Lyttle and Roberta (“Bobbi”) Trask were up talking in the farmhouse family room. Mary was Bradford Lyttle’s wife of two years, and Bobbi was a junior college teacher spending the summer at the Farm with her two children.

At approximately 2:45, the Farm’s dog began barking ominously. Before the women knew what was happening, two masked men burst into the farmhouse and blocked the door. “They had rifles with fixed bayonets, packages of tape and rope and tanks of gasoline strapped to their backs,” Trask recalled in the National Catholic Reporter, September 4, 1968. The men forced the women onto a couch and kept their rifles aimed at them.

Mary Suzuki Lyttle’s account, Minutemen Attack on New England CNVA: A Report (NECNVA, September 28, 1968), describes how the event unfolded. Two more men, armed with pistols, knives, and gasoline, entered the house. After they searched the first-floor rooms, one of them taped her mouth and eyes shut. He was taping Trask’s eyes shut when there was a loud disturbance outside, then the sound of more men entering the room. Trask claimed in the National Catholic Reporterto have heard one of the men say, “This is the state police. Stop where you are.” Suzuki Lyttle’s report said Trask heard one of the intruders respond: “Here come two of them. I’ll take care of them.”

Informed by the FBI about the Minutemen’s planned raid, the state police had positioned officers around the Farm to intercept the intruders. But the intruders had somehow gotten past them and staged their attack. Once the state police realized this, they sent up flares to light the area, waking Carol Swann, whose parents were away that night, in a bedroom upstairs. “I looked out the window and saw dozens of men in masks and camouflage, holding rifles, climbing over the stone walls in the front yard and coming toward the house,” she told me. Confusion about who was who resulted from the fact that the troopers were in plainclothes, making it hard to tell intruder from law enforcement.

The state police swarmed the property and poured into the house. One of the intruders, brandishing a bayonet, charged at a trooper who was coming into the family room. In the melee the trooper’s rifle went off and shot Trask in the thigh. State police and intruders engaged in a shootout that spilled into the adjacent rooms and outside the house.

“Jerry Elmer ran into the bedroom with me and said, ‘Get under the bed, we’re being attacked,’” says Swann. Elmer remembers several residents coming into the bedroom, leading to a “macabre debate” over whether or not to barricade themselves inside.

Behind the farmhouse, where he had been sleeping in a cabin on the property, Hinke was accosted by state police. Two children nearby—likely Trask’s, though not confirmed—screamed from another cottage. One of the intruders who had stationed himself near the cottage kept the door closed so the children would remain safe, Suzuki Lyttle’s report noted.

When the dust had settled, a total of seven people were wounded: two troopers, Trask, and four of the five intruders who were identified as Minutemen. All five were arrested that night. A sixth person, not present at the attack, was arrested at his home on charges of conspiracy to commit arson. Trask was whisked to the hospital in Norwich after a trooper applied a tourniquet to her leg, an action that Suzuki Lyttle’s report claims likely saved her life. One of the Minutemen was blinded as a result of his injuries.

Aftermath

In the days following the attack, CNVA residents stuck to their principles of nonviolence and mutual understanding. That October they sponsored a weekend conference, “The Rise of the Right: The Role of Nonviolence,” which one member wrote in the December 16, 1968, CNVA newsletter “succeeded in making us more aware of the ideas and feelings of people who hold right-wing views.”

In November the five Minutemen pled guilty to charges of aggravated assault, reduced from assault with intent to kill. In December they were sentenced to prison. Speaking of the Minuteman who had lost his eyesight, a CNVA resident told the New York Times: “All of us would rather see our place burned down than to see a Minuteman blinded.”

It was clear the attack had traumatized some. Bradford Lyttle told me that his wife Mary was “completely terrified” by the invasion. Though she had “been through it all,” including civil rights protests, stints in jail, and participation in the CNVA Quebec-to-Guantanamo Walk for Peace, the horrors of that fateful night proved too much. She soon left the peace movement and relocated to Ireland.

Today the Farm is known as the Voluntown Peace Trust and continues the pursuit of nonviolence. CNVA alumni all over the world uphold the organization’s mission. Bradford Lyttle writes and speaks about nuclear deterrence from Chicago, Hinke protests against censorship and works to abolish the draft in Thailand, Elmer is an attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation in New England, and Carol Swann is a somatic therapist and radical conflict facilitator in Berkeley, California. She cites her parents as the primary inspiration for the training program she co-founded, “Somatics and the Performing Arts for Social Change.” Her father passed away in 2003 after doing pioneering work in the community land trust movement. Her mother passed away in 2014, a committed activist and proponent of nonviolence until the very end.

Today the Farm is known as the Voluntown Peace Trust and continues the pursuit of nonviolence. CNVA alumni all over the world uphold the organization’s mission. Bradford Lyttle writes and speaks about nuclear deterrence from Chicago, Hinke protests against censorship and works to abolish the draft in Thailand, Elmer is an attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation in New England, and Carol Swann is a somatic therapist and radical conflict facilitator in Berkeley, California. She cites her parents as the primary inspiration for the training program she co-founded, “Somatics and the Performing Arts for Social Change.” Her father passed away in 2003 after doing pioneering work in the community land trust movement. Her mother passed away in 2014, a committed activist and proponent of nonviolence until the very end.

The Minutemen served their sentences and reentered private life. Stories have been told—most recently by former CNVA member Steve Trimm in an August 1, 2018 article in the Albany, New York Times Union—of their returning to the Farm to seek forgiveness. Considering the legacy of the CNVA, there is no doubt they would have received it. As Barbara Deming wrote in “On Revolution and Equilibrium,” (Liberation, February 1968) published the same year as the attack: “We can put more pressure on the antagonist for whom we show human concern.”

Michael Centore is a resident of Suffield and the editor of Today’s American Catholic.