By Karin Peterson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Against the backdrop of civil and political unrest that resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, another piece of legislation sought to stem the destruction of our nation’s heritage. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, signed by President Lyndon Johnson, gave the federal government a major role in the management of our country’s historical resources. Two key provisions of the law were the establishment of a historic preservation office in each state to represent federal interests and the creation of the National Register of Historic Places to recognize buildings, districts, and archaeological sites that were worthy of preservation. The first building in Connecticut nominated to the National Register was the endangered Amos Bull House at 350 Main Street, the oldest brick house in downtown Hartford. The story of its survival and transformation has many twists and turns, the involvement of many committed individuals, bureaucratic entanglements, and cliff-hanging denouements.

Against the backdrop of civil and political unrest that resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, another piece of legislation sought to stem the destruction of our nation’s heritage. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, signed by President Lyndon Johnson, gave the federal government a major role in the management of our country’s historical resources. Two key provisions of the law were the establishment of a historic preservation office in each state to represent federal interests and the creation of the National Register of Historic Places to recognize buildings, districts, and archaeological sites that were worthy of preservation. The first building in Connecticut nominated to the National Register was the endangered Amos Bull House at 350 Main Street, the oldest brick house in downtown Hartford. The story of its survival and transformation has many twists and turns, the involvement of many committed individuals, bureaucratic entanglements, and cliff-hanging denouements.

In 1955, more than a decade before passage of the National Historic Preservation Act, Connecticut established a state preservation office, the Connecticut Historical Commission (CHC). Initially the commission had no staff, and its members, who were appointed by the governor, acted only in an advisory capacity to the Connecticut General Assembly and the governor. In 1965 the commission hired Herbert Darbee and a supporting secretary to conduct a statewide survey of historic buildings. The following year, in response to the federal legislation, William Morris was appointed director of CHC (now called the State Historic Preservation Office), and in 1969 he hired John (Jack) Shannahan as his special assistant. By then the campaign to save the Amos Bull House was already several years old.

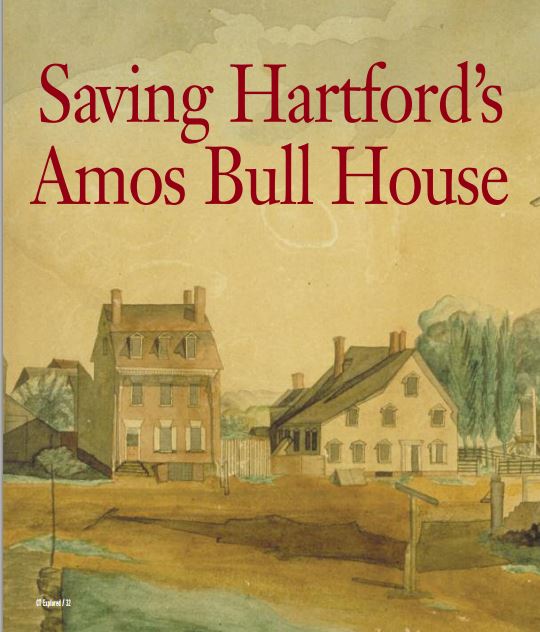

Amos Bull (1744-1825), like many of his contemporaries in turn-of-the-19th-century Hartford, cobbled together many occupations to earn a living, working as a merchant, school teacher, and choir director. In 1788 he purchased a parcel of land on the east side of Hartford’s Main Street and had a brick structure built to serve both as his dwelling and a store. He advertised in December of that year that he was open for business selling dry goods, hardware, and household items. Bull’s account book, now at the Connecticut Historical Society, shows that he sold goods to Daniel Butler, who lived a few doors away in what is now called the Butler-McCook House, a museum belonging to Connecticut Landmarks. In the early 19th century he also ran a school and served as the choir director at the nearby South Congregational Church.

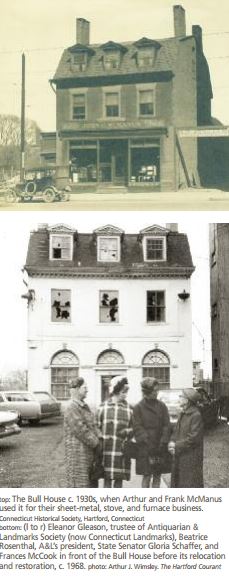

Bull sold the building in 1821 to Isaac Spencer, who lived here with his family while he served as state treasurer from 1818 to 1835, and for many years thereafter. In 1866, when the property was leased to grocer Alvin Squires, the 18th-century façade was updated with a center door flanked by large plate-glass windows. Then, for nearly 50 years, the building housed John C. McManus’s stove store. In 1940 Capitol Motors bought the property and moved the building to the back of the lot, altered the first floor into one large room, and inserted arched windows into the facade. The second floor was rented to another business. The last business to occupy the building was The Apollo, a Greek restaurant. The City of Hartford bought the abandoned, derelict property in 1966 as part of its urban renewal program.

Frances McCook, born in 1877, had spent her entire life in Daniel Butler’s house at 394 Main Street. Over the years she had seen her childhood neighborhood of private homes become a commercial district and then had watched as it deteriorated. In response to the announced demolition plans of the Hartford Redevelopment Agency to clear the property for new construction, McCook wrote an opinion article, “A Plea to Preserve the Amos Bull House,” which appeared in The Hartford Courant on May 9, 1967.

In July, Eric Hatch, chairman of CHC (the governing board of the state office of the same name), took up the challenge and proposed that the Bull House be preserved by moving it and using it as CHC offices. He and others had already explored the possibility with the Hartford Redevelopment Agency (HRA), but no suitable sites had been found. “Miss McCook,” as she was known, offered the rear portion of her property, which extended to Prospect Street, but only if the arrangement would not hinder her garden view. After a lengthy discussion, the commission voted to authorize Hatch to proceed with negotiations.

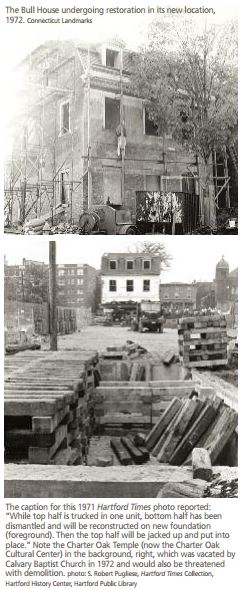

Commission members toured the Bull House in November and found that the second and third floors retained most of their original 18th-century details but the first floor and the facade had been substantially altered. Robert Carter, an Essex-based architect who had experience with historic buildings, was hired to develop plans that accommodated CHC’s needs while restoring the building to its original configuration. Because of the major changes to the first story, it was decided to cut the structure in two and only preserve the upper portion. This was to be moved and set up on top of a newly built first story. Carter was authorized by the commission to file the plans with the state Department of Public Works.

The city then revealed plans to widen Prospect Street by five feet. Could the Bull House still be moved to the rear of McCook’s property? The solution was to turn the structure so that its gable end faced the street. With this orientation, McCook’s adjacent carriage house would partially screen the building from her view. 1967 ended in an upbeat mood, with bids in the works for the move and arrangements with the HRA and McCook well advanced.

On January 11, 1968 a small ceremony was held in the office of Governor John Dempsey. The media alert noted, “This… marks the first acquisition and restoration of an historic property by the State Historical Commission under a program planned to halt destruction of historic resources by neglect or other causes….”

But new troubles arose. Not one bid to move the building was received. The state requested an extension, but the city did not want to delay its demolition program. The second round yielded no bids, either. Meanwhile, Travelers had leased the property to the rear of the Bull House for parking. This lot was in the path to its new location. After several requests to Travelers were unanswered, Hatch contacted a personal friend who was a vice president there, and the necessary permission to cross the lot was granted.

But were there sufficient funds to move and restore the building? In a memo that October Assistant Attorney General Robert Hirtle described to CHC Director Morris an exchange he had had in which HRA’s special counsel Thomas Heslin stated that HRA “would rather smash this building down than to put any money into such a project.” Luckily by this time the structure had been added to the new National Register of Historic Places. Under the National Preservation Act, federal dollars—the HRA’s funding source—could not (and can not) be used to either demolish a listed building or pay for new construction in its place. The Bull House was safe—for the time being.

But were there sufficient funds to move and restore the building? In a memo that October Assistant Attorney General Robert Hirtle described to CHC Director Morris an exchange he had had in which HRA’s special counsel Thomas Heslin stated that HRA “would rather smash this building down than to put any money into such a project.” Luckily by this time the structure had been added to the new National Register of Historic Places. Under the National Preservation Act, federal dollars—the HRA’s funding source—could not (and can not) be used to either demolish a listed building or pay for new construction in its place. The Bull House was safe—for the time being.

Another party at the table was Arthur Leibundguth, director of the Antiquarian and Landmarks Society (A&L, a statewide network of historic properties, now called Connecticut Landmarks). As the saga unfolded, Leibundguth was an active partner and supporter. If the Bull House moved as planned, A&L would be its near neighbor as the Butler-McCook House & Garden were promised as a gift upon the death of Frances McCook. In July 1969 he wrote HRA Executive Director Robert Bliss, “I would like to stress the importance of having both buildings on the same property as being an ideal arrangement. …Both of these buildings are all that remain of the 18th century style of [domestic]architecture that existed in… downtown Hartford…. together… [they]constitute a welcome addition to any urban renewal area and should be thought of as an asset rather than a liability.”

Negotiations and the bureaucratic process dragged on while the forlorn building was the target of vandals; broken windows let in rain, and there was a fire. Although the property was legally the responsibility of the city, CHC paid for it to be boarded up. Meanwhile, cost estimates for the project escalated. The State Department of Public Works now thought the cost would exceed $300,000 and admitted having no experience with 18th-century buildings. The CHC believed it could do the work at much less expense and asked the state attorney general for an opinion of its establishing legislation: Did CHC have the statutory authority to do restoration work on its own properties? An affirmative answer came in June 1970.

The unanswered question remained, however, as to whether the state could justify spending so much public money on this project in the face of so many other needs. Seemingly out of options, the commission voted at its August 1970 meeting to abandon the project. Hatch, still chair of the commission and by this time the State Historic Preservation Officer, forwarded to Washington the request from the redevelopment agency to remove the Bull House from the National Register so the building could be demolished. The fate of the Bull House seemed sealed.

But Hartford Mayor Antonina (Ann) Uccello would not accept this defeat. She sent a letter to Governor Dempsey reminding him about the ceremony that had been held in his office and urging his involvement. She also asked CHC to reconsider its decision and formed a committee to raise funds from private sources. Leibundguth offered to have the non-profit A&L serve as a fiscal agent for donations to the Committee to Save the Bull House. Fundraising got off to a strong start with the promise of $25,000 from the local Howard and Bush Foundation.

Private individuals wrote to the commission expressing dismay at the decision to abandon the fight. Hatch responded to a Mrs. Pratt of Tolland: “…saving the Bull House… is our concern too but we have a duty to perform that regretably [sic]transcends this worthy effort. All of us in this country are suffering from the effects of inflation and heavy increases in taxation. … the Historical Commission finds itself in an extremely uncomfortable position in being forced to make the decision to reluctantly abandon this structure.” Frederic Palmer, a preservationist and board member of A&L, wrote: “What kind of terrible example are you setting others? Think of the discouragement you[r]action will bring…[others]trying to save some place or building….”

In response to the outpouring of support and interest, the commission in October voted to reverse its earlier decision contingent upon the Committee to Save the Bull House’s raising $65,000 by December 31, 1970. The battle was back on.

The Hartford Redevelopment Agency, however, was not alone in feeling the Bull House was not worth saving. The Hartford Times on January 4, 1971 published a letter by Edward Emmons to the editor that argued, “it makes no sense to save such a piece of junk.” The writer buttressed his opinion by quoting one Dr. English, the president of a Virginia preservation organization, but English responded that he had been misquoted and that in fact he felt the building was well worth preserving. At the same time, petitions collected names of individuals who “view the deteriorated Amos Bull house as standing in the way of REDEVELOPMENT,” and individuals appeared at a meeting of the commission to complain that the Bull House was a public nuisance.

Redevelopment staff also felt strongly it was improper for the city to be involved with the restoration of the Bull House because the project did not comply with municipal building codes. Since the state was outside the jurisdiction of city regulations, it was proposed that the state purchase the building so its restoration could be done as desired. To avoid further delays, Jack Shannahan paid the purchase cost of $1 out of his own wallet.

The year 1971 did not start auspiciously. The newly elected governor, Thomas Meskill, froze state spending, and there was a new city mayor, George Athanson. Former Mayor Uccello begged both leaders to support the project, and Meskill agreed to release $44,000 in state funds. At the commission’s June 1971 meeting it was announced that the Committee to Save the Bull House had exceeded its goal, raising $72,834.53. In response to this good news, the commission voted unanimously to move and restore the Bull House.

But new bureaucratic knots appeared: the contracts presented to CHC based on federal Housing and Urban Development guidelines did not comply with requirements for state contracts. And the sole bid on the project would expire unless the contract was rewritten promptly.

The last hurdles having been overcome, Lupachino & Salvatore of Hartford was hired for $188,550 to move the Bull House and prepare it for its new life. Shannahan recalls that the move, in October 1971, attracted great interest as the public expected the building to collapse. He further recalls that, in a grand gesture to prove otherwise, one of the contractors placed a glass of water on the main carrying beam—and not a drop spilled during the moving process. Sadly, Frances McCook was not to know this happy conclusion, as she had died in March, at age 93.

A&L continued to play an active part in the project and supplied period woodwork, including interior doors, floorboards, and wainscoting for use in the building restoration. As the steward of multiple historic house museums, A&L’s Leibundguth also provided practical advice about security systems and placement of electrical outlets.

The official dedication of the Bull House, with Governor Meskill and former Mayor Uccello in attendance, took place on June 10, 1972. There was such ample space for the small staff that initial plans did not include finishing the third floor and designated one room as a museum. During the next 20 years, the staff grew to fill every nook. The proximity of the McCook carriage house offered an unusual answer to the now-pressing need for space. The CHC rented the carriage house from A&L, and the two structures were joined to create a single facility, into which staff moved in 1992.

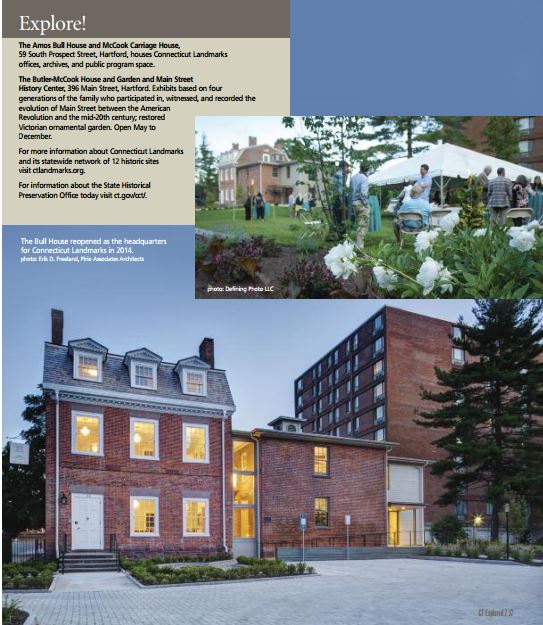

The conjoined buildings remained CHC headquarters until 2003 when the agency became part of the Connecticut Commission on Arts, Tourism, Culture, History and Film, later shortened to the Commission on Culture and Tourism. When the merged staffs were relocated to offices on Constitution Plaza in 2007, the future of the Amos Bull House was once again uncertain. The state policy to consolidate smaller agencies into larger ones made this facility redundant. In an uncanny fulfillment of Leibundguth’s critical involvement long ago, the ownership of the Bull House was transferred to Connecticut Landmarks (CTL), also for $1. After a successful major capital campaign raised funds to refurnish and refresh the buildings, the Amos Bull House and its mate the McCook carriage house debuted as the CTL headquarters in May 2014. Today, in addition to staff offices, the Bull House and McCook Carriage House house a central archives for the organization, a community program space, and a historic garden and green space between the last two of the 18th-century buildings that once lined Hartford’s Main Street.

Karin Peterson is the museum director for the State Historic Preservation Office and once had her office on the third floor of the Bull House. She worked for A&L for 15 years and negotiated one of the carriage house leases between A&L and the State of Connecticut.

Karin Peterson is the museum director for the State Historic Preservation Office and once had her office on the third floor of the Bull House. She worked for A&L for 15 years and negotiated one of the carriage house leases between A&L and the State of Connecticut.

Explore!

The Amos Bull House and McCook Carriage House, 59 South Prospect Street, Hartford, houses Connecticut Landmarks offices, archives, and public program space.

The Butler-McCook House and Garden and Main Street History Center, 396 Main Street, Hartford. Exhibits based on four generations of the family who participated in, witnessed, and recorded the evolution of Main Street between the American Revolution and the mid-20th century; restored Victorian ornamental garden. Open May to December.

For more information about Connecticut Landmarks and its statewide network of 12 historic sites visit ctlandmarks.org.

For information about the State Historical Preservation Office today visit www. ct.gov/cct.

The Butler-McCook House, Winter 2003

Destination: Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden, Summer 2008

Caroline Ferriday & Her Infinitely Generous Family, Fall 2019

Caroline Ferriday: A Godmother to Ravensbruck Survivors, Winter 2011/2012

City, Country, Town: Connecticut Landmarks, Summer 2010

A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House, Fall 2019

Read all of our historic preservation stories on our TOPICS page