by Jeffrey J. White

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

It was a time of mass hysteria and panic. The very fabric of our nation appeared threatened. Government officials called upon citizens to be attentive to their surroundings and their neighbors. “Suspicious” individuals were rounded up, placed in jail, and denied access to legal counsel. This highly charged situation developed in Connecticut from 1919 to1920 as alleged members and sympathizers of the Communist movement were deported back to the motherland in an operation called “The Palmer Raids.”[1]

The end of the second decade of the 20th century was a period of intense nationalism as the United States attempted to protect its flanks from the Germans on one side and the Bolsheviks, who had toppled a fledgling provisional government that had been in place in Russia for eight months, on the other. The continued influx of immigrants to the U.S. from these regions stirred fears that subversive elements would seek to overthrow our own Republic. Much of the fear was directed at labor unions, such as the Union of Russian Workers, the Industrial Workers of the World (“IWW”), and the Communist Labor Party, which were believed to provide a platform for the espousal of Marxist principles—and in some cases the overthrow of the American government. Groups such as the IWW fervently opposed World War I through pamphlets, work slowdowns, and possibly, sabotage.[2] In 1919 alone, there were 3,600 labor strikes nationwide involving four million workers.[3]

In an effort to “stamp out the Reds,” Congress and law enforcement officials moved aggressively. In 1918, Congress (and later that year, the Connecticut General Assembly) passed the Alien Act, which permitted the deportation of “any alien who, at any time after entering the United States, is found to have been at the time of entry, or to have become thereafter, a member of any anarchist organization.” The passage of the Alien Act paved the way for the events that transpired from November 1919 to January 1920 in what are commonly referred to as “The Palmer Raids.”

The raids were the brainchild of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Beyond his role as the nation’s top law enforcement officer, Palmer took a personal interest in the battle against the “Reds.” In April 1919, a nationwide bomb plot was uncovered. Scores of dynamite bombs enclosed in packages were discovered in several cities across the nation. Sixteen packages were found at the main branch of the New York City Post Office, and a slew of packages were found at 18 other post offices. The packages discovered in New York City were addressed to powerful political, judicial, and industrial leaders, including the Commissioner of Immigration, Frederic Howe, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Mitchell Palmer himself. That plot was foiled, but on June 2, 1919, Palmer’s Washington, D.C. home was damaged by a bomb. Newspaper accounts following the attack reported that a radical publication was found nearby.[4]

In response to these attacks, Palmer, aided by a young J. Edgar Hoover, devised a plan, to be carried out around the nation, to strike a death-blow to these subversive forces. These raids were primarily focused on the Union of Russian Workers, “which the government found had advocated the overthrow of government by force because its founding charter committed it to ‘a Socialist revolution by force.'”[5] During the late-night hours of November 7, 1919 (on the one-year anniversary of the founding of the Russian Soviet), 1,100 alleged anarchists in cities across the U.S. were arrested, for the most part without warrants.[6] Of those arrested, 249 individuals were ultimately deported, 51 for being “anarchists” and 184 for simply being members of the Union of Russian Workers.[7]

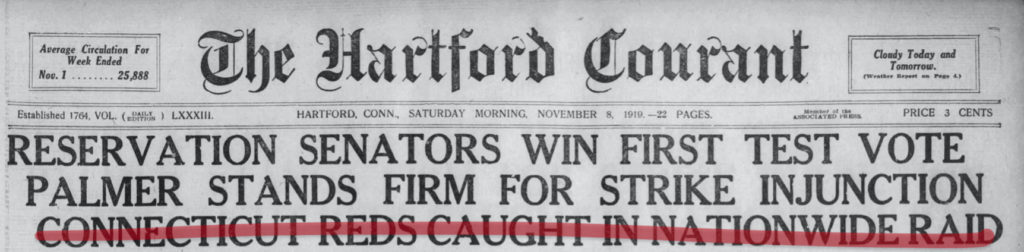

In Connecticut, 41 people were arrested in Hartford, New Britain, Ansonia, and Waterbury. The Hartford Courant reported the following day that the raid was designed to prevent “[a]nation-wide plot to defy governmental authority openly,” which had been “advocated for weeks by combined radical elements throughout the United States, including the I.W.W., anarchists and Russian agitators.”[8]

The raids continued in Connecticut as more arrests were made in Bridgeport, Rockville, and New Britain. The most widely reported arrest was that of Mark Kulesh of Manchester, who was the leader of the town’s Russian Peasants’ and Workers’ Union. During the Kulesh raid, the police seized two machine guns, “red” literature, and other radical paraphernalia. After his arrest, Kulesh “acknowledged that he had no love for the United States, did not approve of its form of government, and was a follower and advocate of the form of government held to be more radical than that of the Bolsheviki.”[9]

While Kulesh’s arrest received considerable attention, the majority of those arrested were simply identified by name, age, and residence. Nearly all of the radicals arrested were men between 20 and 30 years old. These men were brought to Hartford for a hearing in front of U.S. Bureau of Immigration inspector William Clark. Almost immediately, a backlog of detainees overwhelmed Clark and the other immigration inspector assigned to hear these cases. Nevertheless, Palmer instructed officials around the country to expedite these hearings so that deportation could be achieved quickly.[10]

There was a critical difference between these hearings and a run-of-the-mill criminal case. Under the 1918 Alien Law, the burden of proof was placed squarely on the alien to prove that he should not be deported. For those accused, this seemed a monumental task as they were faced with combating the public perception that the government had “strong evidence,” because “it [was]pointed out, if there was not apparently satisfactory evidence against them they would not be held for hearings.”[11] Indeed, William Hazen, who directed the operations of the Department of Justice in Connecticut , stated before the hearings that “in his opinion there was little doubt [that]they would all be ordered deported.”[12] Despite Hazen’s confidence in the ultimate outcome, the evidence against those arrested was tenuous at best. Bruce Shubert, who reviewed many of the immigration files of those arrested during the November raids, notes:

Membership in the Union of Russian Workers was rarely proven. . . . The main evidence against the aliens consisted of a copy of the ‘Manifesto of Anarchists-Communists’ and of affidavits, filed by Department of Justice agents, which were also examples of syllogistic reasoning. The affidavits, exactly alike except for the name of the alien, stated that the accused was an alien, that he belonged to the Union of Russian Workers, that the Union of Russian Workers advocated overthrow of the United States government by force, and that, therefore, the alien was an anarchist.”[13]

Although the government’s evidence may have been weak in some cases, the detainees were handicapped by the fact that the availability of legal counsel was scant at best. For instance, three unidentified lawyers retained to represent some of the detainees withdrew “after the cases were heard and the evidence against them brought out. . . .”[14] It is unclear whether their withdrawal was hastened by strong evidence or by a realization that the odds were stacked against them.

By contrast, Harry Edlin, an attorney from New Haven retained by the Union of Russian Workers, appeared at the Federal Building in Hartford and demanded the right to see a group of detainees from Ansonia. Even though he was retained to represent members of the Union of Russian Workers whenever necessary, his overture was rebuffed by Inspector Clark, who argued that Edlin could not have access to the prisoners before the hearings because “he did not represent a single one of them, but was to appear for all of them.” Edlin responded by stating that “the American people would stand for it just so long as the country appeared to be at war, but when peace was once more declared the federal agents would no longer be permitted to compel the man to appear at a hearing without representation.”[15]

Clark’s rejection was indicative of a pattern of practice by officials in Hartford to deny counsel to the detainees. Notably, these denials were contrary to a Bureau of Immigration regulation that mandated that aliens should be advised of their rights to counsel from the outset of any hearing.[16] Yet it does not appear that these violations were reported; in most cases, the only opposition voices that were heard were those of attorneys hired by the respective labor unions.

Similarly, Rose Weiss of New York City, who had been retained by the Communist Labor Party, was also denied access to the detainees. In response, Weiss asserted that the detainees’ constitutional rights were being violated. Ironically, the detainees’ citizenship—or lack thereof—appears to have been raised to counter Weiss’s position: they were not protected by the Constitution, it was argued, because they were not citizens. Undeterred, Weiss maintained, in the words of the Courant reporter relating her story, that “the wholesale raids that have been waged throughout the country are entirely illegal” and “claimed that men were being deported from the country without being given an opportunity to hear some one say a word in their behalf.”[17] This argument did not gain much traction, however, as evidenced by the Courant‘s placement of Weiss’s comments on page eight, right before a listing of soldiers who had been enlisted to guard the Hartford county jail.

In many ways, the Courant‘s placement of Weiss’s constitutional arguments is emblematic of one overarching theme that arose during the Palmer Raids. During this era, the nation was engulfed in a collective passion for “law and order.” Law enforcement officials, including Palmer, who was touted as potential Democratic presidential candidate, became community heroes and were widely praised in newspaper articles.

The detainees also received widespread news coverage—but little of it was positive. One striking example occurred when 47 alleged anarchists were transported via train from Bridgeport to Hartford. Sixty-seven individuals had been arrested the night before, with 20 released immediately. The alleged radicals arrived in Hartford under heavy guard, and an immediate public spectacle ensued. The Courant reported that:

When the train pulled into the station, a big crowd had gathered to get a glimpse of the Reds. High school pupils had just been dismissed and hundreds of them poured down to the railroad station. They tried to get as near the cars as possible to satisfy their curiosity, but were orderly especially because of the activity of the police who would permit none inside lines drawn about the cars.”[18]

These evocative images may best sum up the mood of the nation in November 1919 as the nation yearned for a return to a time when law and order reigned supreme. Eventually, many of the detainees from the November raids were placed aboard a ship and sent across the Atlantic.

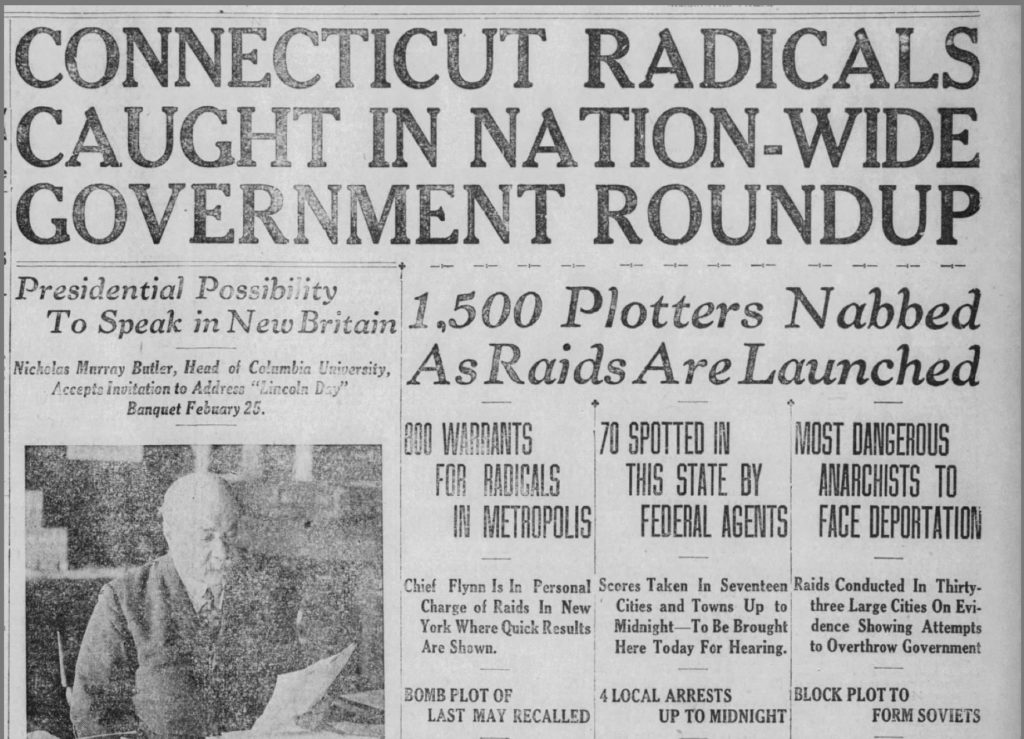

A few months later, Palmer ordered another nationwide raid, this one specifically targeting the Communist and Community Labor parties, to take place on January 2, 1920. The following day, The Hartford Courant’s front-page headline read “Connecticut Radicals Caught in Nation-Wide Government Roundup.” The raids spanned 17 Connecticut cities and towns and resulted in 72 arrests. As with the November raids, Ansonia was a hotbed of activity as 17 people were taken into custody; 12 arrests in Bridgeport followed, and 4 each in Manchester and Hartford.

As before, Hartford was the epicenter of activity as the detainees were transferred to the capital city for hearings. Foreshadowing the obstacles that these detainees would face, the Courant reported that “[i]t is expected the hearings will progress more rapidly than was the case with the last batch, as in making out the warrants it is assumed the government had investigated the individual cases before the final plans for the raids were completed. . . .”[19]

As the days progressed, more was learned about this group of detainees. The first woman radical was taken into custody as officials arrested alleged radical Communist Party leader Mary Muroff of Naugatuck. The Hartford Courant reported that some of the detainees were quite wealthy. Yet, perhaps as a sign of things to come, the Courant, in an almost passing manner, reported that while incriminating evidence had been found, “nothing in the way of explosives or machine guns such as was unearthed in the previous campaign had been brought to light.”[20]

In fact, as with the November raids, the majority of individuals were subject to arrest for their purported membership in organizations such as the Communist or Communist Labor parties. None of the 4,000 to10,000 individuals arrested nationwide during the raids were charged with the bombing plot that was uncovered in April 1919.[21] Indeed, Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis F. Post, who personally reviewed many of the immigration files, wrote after the raids ended that of the 556 individuals ultimately deported, “in no instance was it shown that the offending aliens had been connected in any way with bomb throwing or bomb placing or bomb making.”[22]

Nevertheless, the conditions for these detainees were for the most part the same as for those captured during the November raids. Many waited in the Hartford county jail for weeks, if not months, to be heard. Bail was almost nonexistent, as many bonding companies were unwilling to pay for the release of these dissidents. Scores of family members attempted to see the detainees, with apparently little success. Most important, the policy of denying the detainees legal counsel was approved by a change to the immigration regulations, which effectively allowed government officials to deny legal counsel until the deportation hearing “has proceeded sufficiently in the development of the facts to protect the Government’s interests. . . .”[23] By March 1920, 181 detainees remained in the Hartford county jail. As the costs of detaining these individuals began to mount, a Courant editorial noted that “it is doubtful if there will be any regrets when the last of them has gone somewhere, either released or deported.”[24]

Eventually, though, the tide began to turn in the dissidents’ favor, in large part due to the actions of Secretary of Labor William Wilson and Assistant Secretary Louis Post. Wilson ruled that membership in the Communist Party did not require automatic deportation under the Alien Law; as a result, Post ordered that many of those held be released on bail. Post also restored the immigration regulation that mandated that a detainee had the right to counsel from the beginning of the proceedings.[25] In addition, U.S. District Court Judge G. W. Anderson released many of the detainees, either because their hearings violated the due process clause or the government had not established that the Communist Party advocated the overthrow of the government by force or violence.[26] Through the work of the courts and the Labor Department the fervor would subside by April 1920. Palmer’s tenure as attorney general expired the following year. He never returned to public office.

Although the Palmer Raids ended in 1920, remnants of this period of history would remain in Connecticut law for years to come. For example, a Hartford ordinance banning the display of red flags, which was passed in 1921, remained on the books until 1945. Specifically, the ordinance made it unlawful for any person “to display in any parade, assembly, or other meeting place, the ‘Red Flag’..” The penalty for violating this ordinance was a fine not exceeding $100 or imprisonment not exceeding six months, or both.[27] This ordinance was modeled after a Connecticut state statute, which was part of a series of statutes that outlawed “offenses against the sovereignty of the state.” These provisions were not repealed until 1971, when the current penal code took effect. The U.S. District Court in Connecticut further sealed the “red flag” statute’s fate in 1971 when it held that the statute was unconstitutional.[28]

The events that transpired in Connecticut and throughout the nation from 1919 to 1920 provide a looking glass for ordinary citizens to evaluate the decisions being made today. A citizenry educated in the strength and value of the Constitution is essential-and the earlier that education starts, the better. Recently, a group of Connecticut high school students had the opportunity to learn about the Palmer Raids through a program sponsored by the Center for First Amendment Rights. Such programs help ensure that the Constitution will continue to live and breathe through the actions of the next generation of Americans.

Jeffrey J. White is an attorney at Robinson & Cole LLP in Hartford.

Explore!

Read more Labor History stories on our TOPICS page.

Footnotes

1. For an exhaustive discussion of the Palmer Raids in Connecticut, see Bruce B. Shubert, “The Palmer Raids in Connecticut, 1919-1920,” 5 Connecticut Review 53 (October 1971).

2. Ibid.

3. David Cole, Enemy Aliens: double standards and constitutional freedoms in the war on terrorism (New Press, 2003), at 117.

4. See http://www.xroads.virginia.edu/~UG01/starner/~ams5k/public_html/ONLY_ch03.html

5. Cole, supra note 3, at 119.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Hartford Courant , November 8, 1919, p. 1.

9. Hartford Courant , November 9, 1919, p. 1.

10. Hartford Courant , November 11, 1919, p. 1.

11. Hartford Courant , November 13, 1919, p. 11.

12. Ibid.

13. Shubert, supra note 1, at 57.

14. Hartford Courant , November 19, 1919, p. 2.

15. Hartford Courant , November 9, 1919, p. 2.

16. Shubert, supra note 1, at 58; Cole, supra note 3, at 266 n.18.

17. Hartford Courant, November 13, 1919, p. 11.

18. Hartford Courant, January 3, 1920, p.1.

19. Hartford Courant, January 4, 1920, p. 1.

20. Hartford Courant, January 6, 1920, p. 1.

21. Cole, supra note 3, at 127

22. Ibid. at 123 (quoting Louis F. Post, The deportations Delirium of Nineteen-twenty; a Personal Narrative of an Historic Official Experience, (Kerr 1923) at 192).

23. Cole, supra note 3, at 266 n.18.

24. Hartford Courant , March 17, 1920, p. 18.

25. Shubert, supra note 1, at 62.

26. For an excellent discussion describing the aftermath of the Palmer Raids, see Shubert, supra note 1, at 63-69.

27. Compiled Charter of the City of Hartford , July 1931, Section 511.

28. Anderson v. Vaughn, 327 F. Supp. 101 (1971).