By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2013 Volume 11 Number 4

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

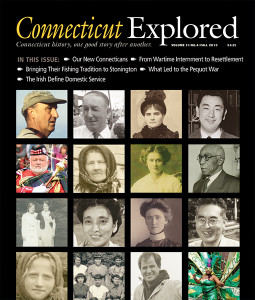

All Connecticans, from the first indigenous settler to the state’s most recent arrival, are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants. The Laurentide ice sheets that covered our state with a mile-high wall of ice 22,000 years ago made sure of that. Immigration has, for most of our history, steadily replenished the Land of Steady Habits with vibrant influxes of new ideas, cultural influences, and social values. Yet a curious anomaly in our immigration pattern—a break in the norm that occurred more than 300 years ago—created an environment that made subsequent immigration a particularly contentious and contested process.

All Connecticans, from the first indigenous settler to the state’s most recent arrival, are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants. The Laurentide ice sheets that covered our state with a mile-high wall of ice 22,000 years ago made sure of that. Immigration has, for most of our history, steadily replenished the Land of Steady Habits with vibrant influxes of new ideas, cultural influences, and social values. Yet a curious anomaly in our immigration pattern—a break in the norm that occurred more than 300 years ago—created an environment that made subsequent immigration a particularly contentious and contested process.

From 1620 to 1640, colonial Connecticut participated in what historians call “The Great Migration”—the rapid immigration of some 20,000 religiously and culturally homogeneous English Puritan refugees to the land they would conquer and remake as a New England. In 1640, with the outbreak of the English Civil War, that migration stopped on a dime. For the next century, New England’s population increased dramatically, but almost exclusively from the offspring of those original 20,000 English immigrants, who obeyed mightily the biblical injunction to “be fruitful and multiply.” On the eve of the American Revolution, this extended New England cousinage numbered more than 183,000 people in Connecticut alone, an extraordinarily self-possessed, white, Anglo-Saxon, Puritan seed-stock whose issue shaped the government, economy, society, and even the land to reflect their own culture and values.

Such a homogeneous and powerful group was not likely to embrace diversity, and when the Irish arrived in the early 19th century, first to dig canals and build railroads, later to flee the Great Hunger, the scions of the Puritans ridiculed the newcomers’ culture and condemned their religion. Anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic hostility was so strong in Connecticut in the 1850s that the nativist American Party won control of Connecticut’s government on a platform to resist foreign or Roman Catholic political or cultural incursion. The state’s six Irish militia units were disbanded in 1855, a policy the state regretted when the Civil War began six years later.

For all their desire to protect their cultural patrimony by keeping out the “other,” the Yankee descendants of the Puritans faced a problem of their own making. Throughout the 19th century they were mounting the machine-tool revolution that transformed New England into the industrial powerhouse that was the envy of the world. The new water- and steam-powered factories—the armories, textile and paper mills, clockworks, munitions plants, and brass and silver works—all depended on a labor force far beyond local capacity. And so, for all their fears, the Yankees came to rely on outsiders to literally make their fortunes, and the floodgates of immigration opened—to Italians, Poles, Swedes, Germans, Russians, Finns, and Lithuanians, who worked the factories, and even the farms the Yankees had depleted and abandoned. American migrants joined the throng, too: African Americans from the South; French Canadians from the North, and Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Jamaicans from the West Indies. By 1940, the homogenous world of the Puritan fathers was no more.

And the transformation continues. Recent decades have seen the arrival of Asians and Spanish-speaking people of many different cultures and nationalities. Each group brings new ideas, presents new opportunities, and poses new challenges. Like the Puritans of old, some Connecticans resist immigrants’ challenges to the status quo as a threat to our state’s—and our nation’s—future. But which Connectican among us can say he or she, too, is not also descended from immigrants who once posed the same challenge to the status quo, the same “threat” to the future?

Walt Woodward is State Historian. Read all of his columns on our BLOG.