By Paulette Clark Kaufmann

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On September 15, 1862, 18 months into the Civil War, 14-year-old Emilie Ely of Madison wrote to her married sister Elizabeth. She told of the family’s activities and the most pressing news: the threat of a draft should Madison not meet its quota for Lincoln’s mid-summer call for 300,000 more men to fight in the Union army. Connecticut was expected to provide more than 7,000 men, of whom 118 were to come from Madison. One of Emilie and Elizabeth’s three brothers had been fighting for the last year, and another had recently enlisted. Would the war claim their youngest brother, too?

Two months earlier, in July, Madison had held a special town meeting to vote “for the purpose of encouraging enlistments.” It was decided to set aside $100 per enlistee, $75 for a bounty to be paid to the enlistee and $25 toward a fund to cover wounds, sickness, and disability should it be needed by the soldier or his family.

In the 1860s Madison was home to more than 400 families with 338 men between the ages of 20 and 45, most of whom were engaged in farming. But by early September the bounty offer had produced just 57 volunteers, too few to meet Madison’s quota of 118. A call-up was announced. If Madison was not able to meet its quota in the two-day period, the town’s only remaining option was to resort to a draft.

In her letter Emilie described the first day of the call-up, during which only half of Madison’s remaining quota was met. Emilie provided an hour-by-hour account as men came forward, singly or by twos. Thirty-three men eventually enlisted bringing the total to 88, one of whom was 21-year-old Charles, the youngest of Emilie’s brothers, who had just graduated from Yale.

The quota unmet, the town scheduled a draft to begin at 9:00 the next morning.

Not all of Madison’s townspeople shared the same feelings about slavery and the war. The issue of slavery aside, many residents had commercial ties to the South, where the cotton economy provided much opportunity. The most successful of them was Madison-born Daniel Hand, who had lived and conducted business in Augusta, Georgia from the 1820s up through the declaration of war, by which time Hand had relocated to New York City, from where he managed the firm’s Northern business relationships. But it was during the Civil War that his firm truly flourished (under the management of Hand’s Southern partner), earning him a small fortune, part of which he donated to the town of Madison after the war to establish a school that would carry his name. (The Hand Academy, a quasi-public high school that charged modest fees for attendance, later became the Daniel Hand High School when public high school education became the norm in the state.)

Some residents responded early to the Abolitionist cause but found themselves in the minority. Around 1839 Chloe Scranton Bushnell, known for her support of the anti-slavery cause, invited friends and sympathizers to hear the noted abolitionist and clergyman Ichabod Codding speak in her parlor. Codding was an eloquent and stirring speaker on the subject of liberty and the cost of slavery. As news of Codding’s presence spread, the Bushnells’ house was mobbed by a group of villagers who gathered outside to pelt the building with rotten eggs. Wanting to protect his mother and her guests, 15-year-old Nathan Bushnell took an old Revolutionary War musket down from the kitchen wall and stood pointing its barrel out the open front doorway to deter the troublemakers from further assault.

As the prospect of a civil war loomed mid-century, feelings about the Union’s position were mixed. Mass meetings in favor of the war were held, complete with torchlight parades, flags flying on the town green at full mast, and house windows lit with candles. However, at least one Southern sympathizer, Moses J. Stannard, would not place lights in his window and flew a Southern flag to show his support for Southern secession, until he was arrested in September 1861 on orders of the U.S. State Department and imprisoned at Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor for disloyalty to the American cause.

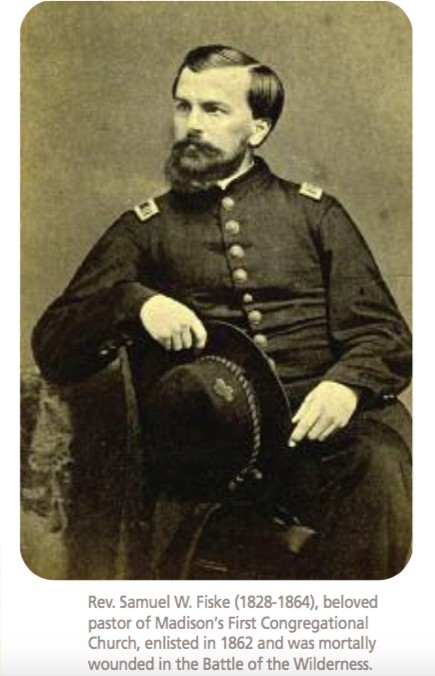

Emilie’s brother Charles was just one of many Madison residents who responded to the call-up in 1862. Rev. Samuel W. Fiske, the much beloved pastor of Madison’s First Congregational Church, set an extraordinary example by signing his enlistment papers during a church service. Two years into the war, during the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, Rev. Fiske was struck in the neck by a Confederate bullet. News of his wounding and hospitalization was telegraphed to New England papers, which posted day-by-day accounts of his lingering death. The man who had preached such memorable and meaningful sermons from his pulpit and who, as “Dunn Browne,” wrote a regular column of acute observations about the war for the Springfield Republican, was now silenced forever.

Emilie died within six months of her brothers’ departure, and she never saw them again. Edgar returned home to farm alongside his father; Willoughby suffered chronic illnesses after the war and made a scant living as a grocer, and Charles became a well-known educator of the deaf.

Paulette Clark Kaufmann was vice president of the Madison Historical Society. She is a former New York book publishing and marketing executive who now devotes her time to researching historical persons and themes for articles and exhibitions.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War in the Spring 2011 and Winter 2012/2013 issues, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.