By Marty Podskoch

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2010

Subscribe to Receive Every Issue!

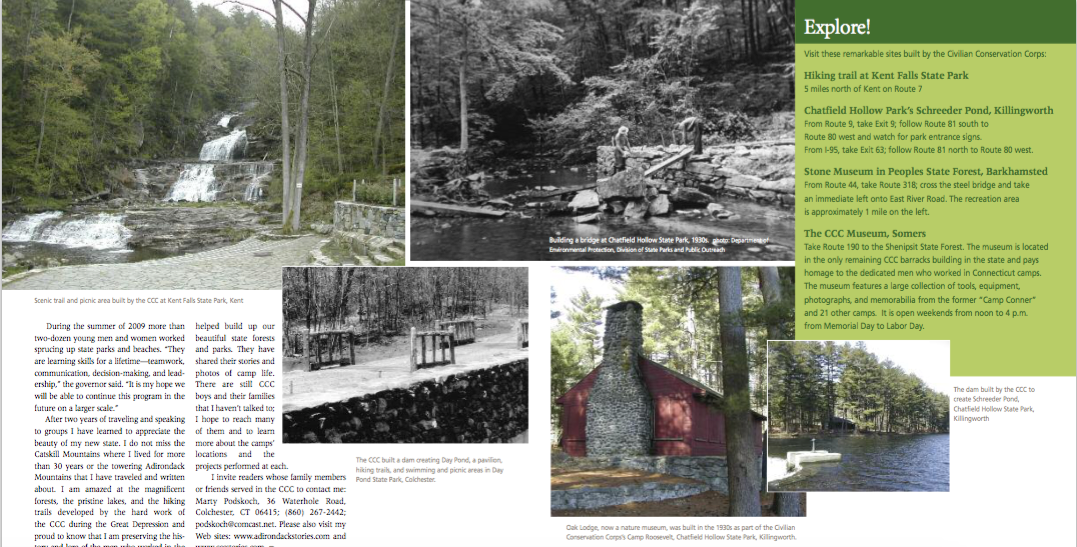

Have you ever hiked the scenic trails in Chatfield Hollow State Park in Killingworth, taken a swim on a hot day at Day Pond State Park in Colchester, or climbed the breathtaking trail along the falls at Kent Falls State Park? If you have you owe it to the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Connecticut’s state parks and forests from 1933 to 1942. During the Depression, this federal program paid thousands of young men all over the state to build campsites, cut trails in the forests, plant trees, and perform a hundred other conservation jobs. We have inherited thousands of acres of 67- to 75- year-old conifers that were planted by the “CCC boys.” Many miles of the gravel roads they built, some featuring stone bridges and culverts, were constructed so well that they remain in safe use all these decades later. Today we make use of dams, lakes, ponds, picnic pavilions, and recreation areas that came into being as the companies of CCC boys bent their backs to the work at hand.

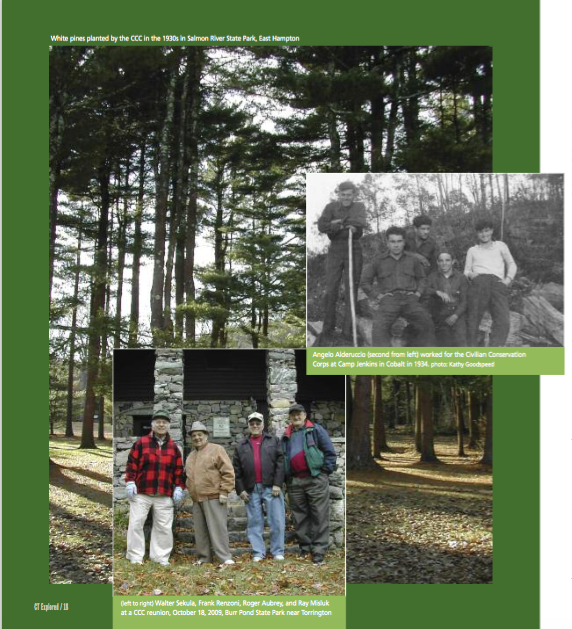

Have you ever hiked the scenic trails in Chatfield Hollow State Park in Killingworth, taken a swim on a hot day at Day Pond State Park in Colchester, or climbed the breathtaking trail along the falls at Kent Falls State Park? If you have you owe it to the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Connecticut’s state parks and forests from 1933 to 1942. During the Depression, this federal program paid thousands of young men all over the state to build campsites, cut trails in the forests, plant trees, and perform a hundred other conservation jobs. We have inherited thousands of acres of 67- to 75- year-old conifers that were planted by the “CCC boys.” Many miles of the gravel roads they built, some featuring stone bridges and culverts, were constructed so well that they remain in safe use all these decades later. Today we make use of dams, lakes, ponds, picnic pavilions, and recreation areas that came into being as the companies of CCC boys bent their backs to the work at hand.

The Civilian Conservation Corps began during the Great Depression, when millions of people in the United States were unemployed. President Herbert Hoover, unable to jumpstart the economy, ran for reelection in 1932 promising a “chicken in every pot.” His opponent, Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York, promised a “New Deal.”

Roosevelt won the election. At his inauguration on March 4, 1933 he said, “I propose to create a civilian conservation corps to be used in simple work, not inter- fering with normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control and similar projects.” His goal was to employ millions of young men from poor families in restoring our natural resources. By 1933, 44 percent of Connecticut had been deforested by clear-cutting, charcoal production, agricul- ture, pests and diseases, fire, and erosion. As governor of New York, Roosevelt had already tested a similar program in which thousands of unemployed men reforested one million acres of land.

On March 27, 1933 Roosevelt gave Congress the Emergency Conservation Work bill. Congress passed it promptly, and Roosevelt signed it on March 31. Roosevelt promised to recruit 250,000 men nationwide and have them report to CCC camps by July. He kept that promise. Over its lifetime, the program would employ more than 3 million young men. It turned out to be the largest peacetime mobilization of manpower and equipment in the nation’s history. The effort required the cooperation of many federal agencies. The Labor Department worked with state and local relief agencies to select the enrollees. The departments of agriculture and interior planned and organized the projects. The War Department was in charge of building and administering each camp. The Army provid- ed the food, clothing, medical care, and lodging. In April, 1933, Robert Fechner, a Democrat, was appointed as national director of the Emergency Conservation Work program, later called the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Federal law required each applicant to be male, between the ages of 18 and 25, unmarried, unemployed, healthy, not in school, and capable of doing work. Many of the boys had quit school after eighth grade to help their families and so were eager to

join because they would be earning $30 a month. At that time inexperienced help was earning around 10 to 15 cents an hour, or roughly $20 a month. The federal govern- ment sent $25 straight home to the parents, allowing the boys to keep $5 for themselves. In addition, the young men received three meals a day, clothing, shelter, and medical care.

Angelo Alderuccio from Bristol worked at the Cobalt camp in 1934. He said, “I was happy joining the CCC because my mother was going to get some money, and it took me off the streets.” Another enrollee, Ed Kelly of Woodbury, said, “I was interested because there were no jobs and I had card- board in my shoes to cover the holes. There were eight children in my family and the money I earned helped my parents.”

Angelo Alderuccio from Bristol worked at the Cobalt camp in 1934. He said, “I was happy joining the CCC because my mother was going to get some money, and it took me off the streets.” Another enrollee, Ed Kelly of Woodbury, said, “I was interested because there were no jobs and I had card- board in my shoes to cover the holes. There were eight children in my family and the money I earned helped my parents.”

On April 6, 1933 Connecticut had its first enrollee, and by May 31 eight camps had been established, with 200 to 250 men assigned to each camp. By July 29 another camp had been added, and at the end of December Connecticut had 10 camps employing about 2,722 men.

During the past two years I have gathered information about the CCC camps for my planned book, Civilian Conservation Corps Camps of Connecticut: Their History, Lore and Legacy. I have given more than 60 talks at libraries, historical societies, and retirement homes. CCC members and their families have come to me and shared their stories and pictures.

When I visited Niantic in April 2008 I met Carl Stamm, a retired state Department of Environmental Protection parks and forest supervisor, who offered to help search for the location of the CCC camps lost when buildings were removed shortly after the camps were closed. It was a great adventure for both of us trying to find concrete foundations, pipes, wells, and buildings amidst debris, trees, and brush.

As we traveled I realized how fortunate I was to have moved to such a beautiful state. My wife and I had spent 33 years teaching and raising our family along the West Branch of the Delaware River in the Catskill Mountains. In 2005 we moved to Colchester, Connecticut to be close to our daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughters. We built our home right next to the Salmon River State Forest, just a mile from a CCC campsite.

In spring 2008 Carl and I visited Chatfield Hollow State Park in Killingworth. The park roads were closed to vehicles, but the park was packed with hikers. It was at this state forest that the first CCC camp, named Camp Roosevelt in honor of the president, was established. A group of 250 young men arrived on May 23, 1933. The young men set up Army tents and camped until wooden barracks could be built. Their largest project was building a stone dam that created Schreeder Pond. They also built a beautiful Adirondack-style building called Oak Lodge along the pond, 23 miles of truck trails, and miles of hiking trails. The camp closed on March 31,1937. Since then thousands of visitors have come to the pond each year to enjoy swim- ming, hiking, and picnicking.

Ed Gentile of Kensington was one of the men who built Schreeder Pond. He remembered, “We had a tractor pulling a scoop to make the pond. Recently my grandson told me he went fishing at Chatfield Hollow. I almost flipped and told him I played a part in building it.”

Ed Gentile of Kensington was one of the men who built Schreeder Pond. He remembered, “We had a tractor pulling a scoop to make the pond. Recently my grandson told me he went fishing at Chatfield Hollow. I almost flipped and told him I played a part in building it.”

The towns nearby benefited from the camps because the CCC hired local experi- enced men (called LEMS) as foremen to train and work with the boys. They taught them masonry, carpentry, forestry, mechan- ics, and cooking skills.

Each camp also worked on programs to prevent fires. Teams of 10 men apiece were trained to fight fires; many teams could leave the camp within one minute of receiv- ing a call. The CCC built a network of truck trails throughout the forest, enabling them to quickly get to a fire. They also built 1,000 water holes on state land and another 200 on private land to provide water to combat fires. Today, hikers frequently find these stone-lined holes, each about 6 feet deep and located near a spring, along trails.

Since the average enrollee had only been in school through eighth grade, each camp had an education advisor who held evening classes for interested boys. Those classes included conservation and forestry, machine construction, photography, reading, archery, mechanics, and writing.

The CCC also helped residents recover from the devastating 1936 flood and the 1938 hurricane. Ed Kelly said,

I was in Camp Britton, Windsor, during the 1936 flood. We got into boats and rescued people in their homes. The Connecticut River was right up to the bridge in Poquonock. In Wilson, a suburb of Hartford, water was up almost to the roofs. The timbers came down the river from Vermont and stacked up around the submerged bridge. We tried to rescue one guy but he didn’t want to leave because he had a barrel of wine in the cellar. His chickens were on the grape arbor. I can still hear the rats squeal- ing on furniture and junk floating down the river.

After the flood we went to Hartford to clean up the town. At night after we got back to camp we were filthy. Our clothes were steamed to kill any bacte- ria so we wouldn’t get sick.

After the clean up the Governor and the Mayor of Hartford had a big party for us. They made speeches about our contributions. We each got a watch and big dinner. Inscribed on the watch was ‘Hartford 1936’ and it was made in Bristol. I wish I had it today.

Two CCC camps, Britton (in Windsor) and Fechner (in Danbury), were primarily “bug camps.” The boys in these camps fought blister rust that attacked white pine trees. The CCC removed currant and goose- berry bushes surrounding those trees because they were the hosts of the disease.

Enrollees also fought gypsy moths by band- ing trees to prevent larvae from crawling up the trunks and destroying egg clusters by coating them with creosote. Camp Fechner removed and burned more than 10,000 trees affected by the Dutch elm disease.The campsite, with its old mess hall, is today rented as a shooting range.

In other CCC forestry projects, Camp Graves’s boys built the beautiful Mountain Laurel Sanctuary in Nipmuck State Forest in Union, a must-see in June when the state flower is in full bloom. They also thinned trees in Shenipsit Forest and improved roads on Soap Stone Mountain.

In the late 1930s enrollee applications declined as employment opportunities increased. By 1941 the number of enrollees nationwide had decreased from a peak of 600,000 to just 200,000. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entrance into World War II, the country needed its young men for the war effort. The CCC program, while never officially closed, ceased to receive funding.

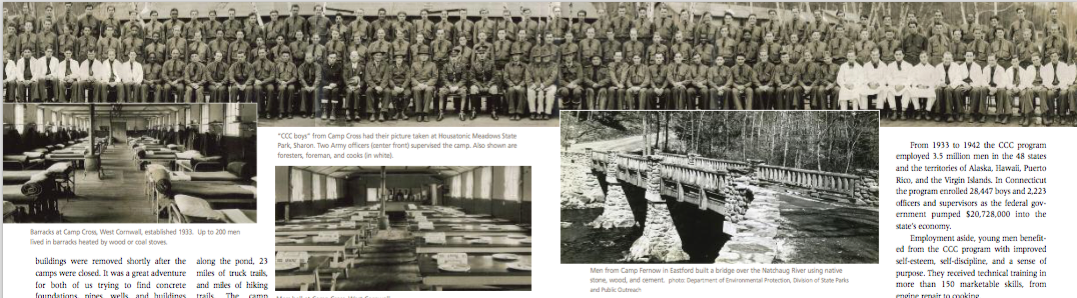

From 1933 to 1942 the CCC program employed 3.5 million men in the 48 states and the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. In Connecticut the program enrolled 28,447 boys and 2,223 officers and supervisors as the federal gov- ernment pumped $20,728,000 into the state’s economy.

Employment aside, young men benefit- ed from the CCC program with improved self-esteem, self-discipline, and a sense of purpose. They received technical training in more than 150 marketable skills, from engine repair to cooking.

Most of the men I interviewed felt the CCC was an important part of their life. Alderuccio said, “I learned to get along with everybody. We worked, ate, played, and slept together. We were tired at the end of the day. There was togetherness for all of us.”

With our nation experiencing one of the worst financial crises since the Depression, many are calling for a restoration of the CCC. It would not only give our young folks jobs but would also help them to develop a strong work ethic, learn skills, and develop and experience the satisfaction of building useful, enduring projects and conserving our natural resources.

Governor Jodi Rell, whose father was in the CCC in North Carolina, said in 2009, “Good ideas never grow old. The original CCC helped transform our national and state park system, including parks in Connecticut, and was a valuable experience for the young men who participated. That is why I want to bring the concept back this year in the form of the Connecticut Conservation Corps.”

During the summer of 2009 more than two-dozen young men and women worked sprucing up state parks and beaches. “They are learning skills for a lifetime—teamwork, communication, decision-making, and lead- ership,” the governor said. “It is my hope we will be able to continue this program in the future on a larger scale.”

After two years of traveling and speaking to groups I have learned to appreciate the beauty of my new state. I do not miss the Catskill Mountains where I lived for more than 30 years or the towering Adirondack Mountains that I have traveled and written about. I am amazed at the magnificent forests, the pristine lakes, and the hiking trails developed by the hard work of the CCC during the Great Depression and proud to know that I am preserving the his- tory and lore of the men who worked in the Civilian ConservationCorps.

After two years of traveling and speaking to groups I have learned to appreciate the beauty of my new state. I do not miss the Catskill Mountains where I lived for more than 30 years or the towering Adirondack Mountains that I have traveled and written about. I am amazed at the magnificent forests, the pristine lakes, and the hiking trails developed by the hard work of the CCC during the Great Depression and proud to know that I am preserving the his- tory and lore of the men who worked in the Civilian ConservationCorps.

I have also been very fortunate in meeting the men who more than 70 years ago helped build up our beautiful state forests and parks. They have shared their stories and photos of camp life. There are still CCC boys and their families that I haven’t talked to; I hope to reach many of them and to learn more about the camps’ locations and the projects performed at each.

I invite readers whose family members or friends served in the CCC to contact me: Marty Podskoch, 36 Waterhole Road, Colchester, CT 06415; (860) 267-2442; podskoch@comcast.net. Please also visit my Web sites: www.adirondackstories.com and www.cccstories.com.