(c) CONNECTICUT EXPLORED Inc. FALL 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

The insurance companies of Hartford hummed into activity as usual on the morning of April 18, 1906. It was a warm and fair day, a Wednesday. No rain was forecast. Front-page news in The Hartford Courant was the continued tense negotiations between coal-mine owners and the United Mine Workers of America; on the West Coast, a brand-new underwater telegraph cable finally linked the U.S. to China.

As the day wore on, there was no physical sign in Connecticut that an earthquake had taken place in the predawn hours some 3,000 miles away on the country’s Pacific coast; tremors reached only as far east as central Nevada. In a region known for its seismic activity, this massive quake was far worse than any previously recorded. Though lasting less than a minute, the earthquake set off a cascade of events that would bring cosmopolitan San Francisco face to face with its own fragility.

The quake, rated an 8.3 or a 7.8 in magnitude depending on the scale used, was centered just a couple miles off the city’s shoreline. San Francisco, with a population of more than 400,000, was a boom city that had taken off after the gold rush. It was made up mostly of quickly assembled wood-frame buildings, many of them situated on filled land that had originally been part of San Francisco Bay-two conditions that made structures particularly vulnerable to earthquakes. Nevertheless, a report prepared by University of California professor Albert W. Whitney for the city’s chamber of commerce months after the quake asserted that “the structural damage [due to the quake]was probably on the whole not large” and that “the business of the city could have gone on with very little interruption if there had been no fire..”[1]

Word of the quake soon reached Hartford by telegraph. Even as it did, the 30 or so fires that would ignite from overturned lamps, broken gas lines, and compromised chimneys (including the “Ham and Eggs” fire, allegedly started by a woman preparing breakfast) were well established and rampaging through scattered areas around the city. By this time, too, the San Francisco fire department, its state-of-the-art alarm system disabled and its fire chief mortally wounded, was becoming all too aware that the city’s water mains had busted as well. Only a few cisterns of water remained to fight the growing conflagration; even sea and sewer water would have to be used. Meanwhile, soldiers under the command of Brigadier General Frederick Funston, a Spanish-American War hero, arrived to help keep order and fight the fire. Though Funston was lionized after the disaster, some of his actions remain controversial; in fact, his bringing in the troops was illegal, as martial law had not been declared.

In an attempt to create firebreaks (building-free expanses that flames would be unable to cross), the Army resorted to widespread dynamiting of homes and businesses. Unfortunately, the lack of skill of those handling the explosives, the flawed strategy with which the explosives were employed, and the nature of the explosives themselves mostly served to spark additional fires.

When the last of the conflagrations touched off by the quake was finally extinguished on April 21, a full 74 hours after the original tremor, Hartford insurers confronted the worst loss they had ever seen. San Francisco’s financial and city centers were virtually demolished; 500 city blocks, or 28,000 buildings, were lost. Among the ruins were banks, department stores, factories, warehouses, shops, hotels, libraries, art galleries-even the luxurious Grand Opera House, where world-famous tenor Enrico Caruso had performed to great acclaim the night before the quake. Half of the city’s population was homeless. According to Professor Whitney’s 1906 report, if all the claims related to this catastrophe were paid in full, the effort would wipe out all the fire-insurance premiums collected over the preceding 50 years.[2]

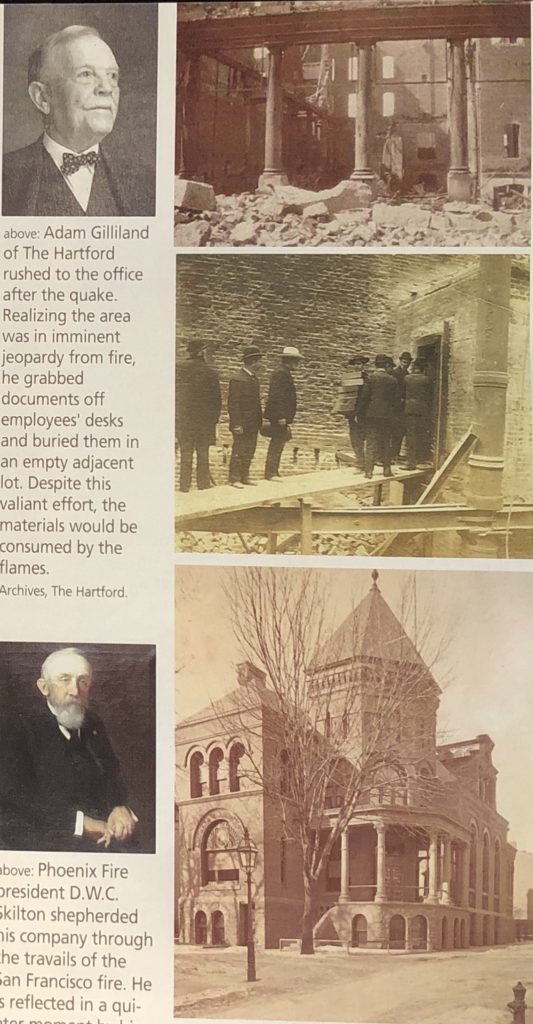

top left: Adam Gilliland of The Hartford’s San Francisco office. Archives, The Hartford. top right and middle: One the vault remained of Aetna’s San Francisco office. Archives, Ace Group, Philadelphia. Bottom left: Anna Ball Pierce, Phoenix Fire president “D. W. C. Skilton,” Hartford Art School. Bottom right: Connecticut Fire Insurance Company, Prospect and Grove streets, Hartford, 1885. photo: C. T. Stuart. Archives, The Travelers

Hartford’s Fire Insurance Companies

Connecticut’s fire insurance companies had survived their share of great losses in the past. Nearly every urban conflagration since the mid-19th century-of which there were many in the days before smoke alarms and sprinkler systems-had been keenly felt by the insurance sector. On the plus side, the active response of Hartford’s six major fire insurers to these incidents had bolstered their reputation, and that of the growing property-casualty insurance industry, throughout the U.S.

At the time of the San Francisco disaster, the Hartford Fire Insurance Company, the city’s oldest , was already nearing its century mark. Since its founding in 1810, it had covered some significant losses, including nearly $2 million after the 1871 Chicago fire (in which 18,000 buildings were consumed). The company, whose cash reserves totaled more than $5 million and total assets topped $18 million, opened its Pacific department in San Francisco in 1870.

The Aetna Insurance Company, founded in 1819, had flourished independently from Aetna Life, its life insurance twin, since 1853. Its policyholders had also weathered devastating fires, including the Chicago blaze in 1871, for which the company paid out almost $3.8 million. But Aetna had flourished and expanded in the intervening generation and, under the presidency of William B. Clark, had by the time of the San Francisco fire just moved into more spacious quarters in a new building on Hartford’s Main Street. It had a cash capital reserve of $4 million and total assets of more than $16 million.

A San Francisco-based agent for Aetna began selling policies on the West Coast in 1858. Eight years later, the company opened a Pacific branch in the city. A 1956 Aetna publication notes the success of this western business: “Every year except 1906.the business yielded handsome profits.” [3] It was a popular insurer among San Francisco’s Chinatown residents.

Connecticut Fire Insurance Company was founded in 1850. Its president in 1906 was John D. Browne, a former secretary of Hartford Fire, and the company’s headquarters were located in a beautiful Italianate-style building at Grove and Prospect streets. Until 1906, none of its losses had topped $300,000. It had a capitalization of $1 million and more than $5 million in assets.

Phoenix Fire Insurance Company was just over 50 years old, having been founded in 1854. Its business history illustrated the intimacy and interconnectedness of Hartford’s fire insurance community. Aetna’s president Clark had learned the fire insurance trade at Phoenix under the tutelage of that company’s president, who had once been the Aetna’s secretary. In 1906, Phoenix Fire’s president was Civil War veteran D.W.C. Skilton, who had begun his insurance career at Hartford Fire. Among the company’s previous losses were $937,219 in the Chicago fire of 1871 and $385,956 in Boston’s conflagration of 1872. The company had $2 million in capital; total assets topped $8 million.

Settling San Francisco’s Claims

About 90 percent of San Francisco’s properties were insured against fire, but underinsurance was endemic. Earthquake damage was not covered in most policies; some insurers, including Phoenix Fire, even had specific earthquake clauses, but the Phoenix waived such clauses in settling its San Francisco claims despite legal counsel to the contrary.

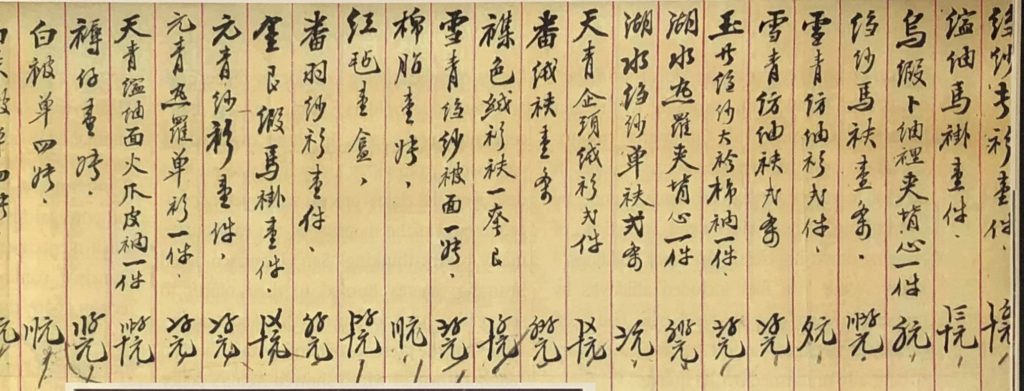

Inventories of lost property were submitted by Aetna policyholders in Chinese. Archives, ACE Group, Philadelphia

Some insurance companies proposed discounting claim payments by 25 percent because the fires had been caused by the earthquake. When news of the proposed discount leaked to the press, the insurance companies that had voted for the so-called “horizontal cut” (including National Fire of Hartford, whose president, James Nichols, defended the policy in San Francisco newspapers) were derisively dubbed the “six-bit” companies. The firms that voted against the discount proposal, including some of Connecticut’s most prominent (Hartford Fire, Aetna, Connecticut Fire, and British-owned Orient) became revered as the “dollar-for-dollar” companies. In addition, according to the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce report, “.there was no serious attempt made in general to escape paying for damage done by dynamiting “-the widespread practice of bringing down hopelessly damaged buildings. [4] Many Aetna Fire files included affidavits by property owners or employees who had been on site stating that that the lost buildings had been structurally unharmed by the quake

In those days, owners tended to take out multiple policies on their property-sometimes from 20 or more insurers-because insurance companies limited coverage to reduce their liability. Policies of $10,000, $5,000, $2,000 or less were the norm, even for large businesses. One notable exception was the $100,000 Hartford Fire policy on the J.A. Folgers & Co. coffee office and warehouse. The Hartford Courant reported the day after the quake that Hartford fire insurers “had said.that they expected to pay their losses promptly and without embarrassment.” Hundreds of adjusters and company officials from around the country headed to San Francisco. The number of claims would be daunting: more than 11,000 claims for the six fire insurers (Hartford Fire, Aetna, Connecticut Fire, Phoenix, National Fire, and Orient Insurance), with the majority (4,972 claims) against Hartford Fire.

Extensive inventory lists, many from the displaced residents of Chinatown, help give an idea of the human scale of the disaster and of the cost to replace lost goods. For instance, an inventory submitted for the $18,165 loss of the general store of Sue Shing Lung included ginger, wine, tea, melon seeds, roast geese, and opium; a penciled notation by the adjuster indicates that the last item was not covered. Another inventory, for a $607.30 loss, included a Shaw piano (value $400), numerous books, articles of clothing, and musical scores.

Copies of policies were kept locally by agencies and by policyholders; home offices didn’t generally keep copies. In those cases where paperwork from either party in California was destroyed, the claims process was severely compromised. On the morning of the earthquake, many quick-thinking San Francisco-based insurance agents hurried to their offices to secure important documents. One Aetna underwriter had the presence of mind to stash the vital Sanborn maps, which showed Aetna’s policy obligations in detail, in a vault that was hoped to be fireproof. After weeks of waiting for the vault to cool enough to prevent “spontaneous combustion” of the materials inside, the vault was opened and, according to correspondence from President Clark to company agents, “contents [were]found intact, not a paper scorched.”

Some insurers, however, did not fare so well. The Pacific office for Hartford Fire lost one of two safes on its premises. One set of maps survived the blaze-“badly scorched but not illegible” -and proved invaluable in settling claims.[5] However, the maps were incomplete. Corroboration for the large Folgers policy could not be found; the office manager settled the claim on the basis of memory.

Logistics were another complication. Their offices burned out, most California-based agents moved operations to Oakland or Berkeley. For a while, Hartford Fire’s office manager, Adam Gilliland, opened up a makeshift office in his own home and would bury important documentation in a zinc-lined box in his backyard every night for safety. A new Aetna office was established in San Francisco before the end of April, less than two weeks after the fire.

Because so many insurance firms had policies for the same lost piece of property, many firms decided to work together to estimate losses for complicated claims. The “dollar-for-dollar” companies, including Aetna, Hartford Fire, Connecticut Fire, and Orient, grouped together, creating an organization that was known as the “Thirty-Five Companies” and was led by an internal body called the Committee of Five.

Reinsurance, a way to spread the risk beyond the principal insurers, had existed for decades, but its merits were fully revealed after the San Francisco conflagration. Aetna was able to reclaim more than a quarter of its gross loss through its reinsurance partners-recouping more than $1 million. Phoenix Fire had gross liability of more than $2.4 million, but it held reinsurance policies worth nearly a half million dollars, which were paid off by other firms. The salvage of reusable materials from the damaged buildings (including many, many charred bricks, no doubt) reduced the insurer’s final payout by another $148,000.

Reputations Rise from the Rubble

Newspapers seemed intent on reporting insurance companies’ “gross incivilities,” in dealing with claims, but the Connecticut insurers largely evaded bad press. [6] Hartford Fire and Connecticut Fire settled their claims in full, minus one or two percent deducted because of their speedy payout in cash; Phoenix eventually did the same for its policyholders. The Orient of Hartford paid an amount equivalent to about 93 percent of the total value of its claims, minus a percent or two for cash. An industry watchdog reported that the company was “undoubtedly able to pay in full” and that its “methods [were]sharply criticized.” [7] (Even the National, which had favored the 25-percent across-the-board discount, ultimately paid about 94 percent.) Aetna was the most generous of all, settling claims at 100 percent and taking no discount for cash. One commercial policyholder wrote a glowing letter to the Aetna’s agents, saying, “We beg at this time to express to you our appreciation of the courteous treatment extended.by all persons connected with the Aetna Insurance Co..[T]he losses were adjusted with a minimum of delay, and the writer was put to no more trouble than to give your adjuster such information as sound business policy dictated that he should have.”

In fact, most insurers were extremely conscious of retaining their good reputation from the outset. A May 1906 circular to Connecticut Fire agents from the company’s president states: “All clearly Total Losses must be paid in full. We must retain our reputation for square dealing.”

Ultimately, Aetna paid less in claims for San Francisco ($2,983,000) than it did for the Chicago fire. Connecticut Fire settled its claims for $2,374,057. Phoenix Fire paid $1,771,103, while National Fire’s total was $2,569,578 and Orient’s, $792,981. Hartford Fire had the greatest liabilities of all: a gross loss of $10,276,500, which reinsurance and salvage cut down to $6,766,937. [8] A later Hartford Fire publication states that the full amount ultimately paid was $11,557,365.

Even with decades’ worth of premiums siphoned away, the insurance companies were still rich with investments. Of the nearly $7 million in cash assets that Phoenix Fire held in 1904, about $4.5 million were in corporate and railroad stocks and bonds. It also had sizable holdings of local bonds and more than a million dollars in bank stocks.

Companies in the past had been prompted to sell shares to pay off their claims. After the 1871 Chicago fire, Aetna found itself in the red even after wiping out its reserve fund, selling off stocks and bonds, and borrowing more than a quarter of a million dollars. To close the gap, it sold 15,000 additional shares in the company, thus raising $1.5 million to cover claims. In May 1906, Aetna’s directors authorized the borrowing of $2 million to settle claims; this, combined with other company funds, paid for the San Francisco losses. According to The Hartford Courant , those who inquired whether Aetna’s securities would be sold (perhaps on the cheap) were disappointed.

Other firms were not so fortunate: Connecticut Fire was forced to sell 5,000 shares to cover its losses. And in another strange parallel, Hartford Fire officials went to an Aetna director, J.P. Morgan, for his personal assistance. With his help, the company issued 7,500 shares of stock, all underwritten by J.P. Morgan and Co.; the effort raised $3.75 million. In the wake of the fire, some 40-odd fire insurers from around the country and around the world paid about $235 million (equivalent to about $5 billion today).

In October 1907, Aetna’s president William Clark announced that all claims had been settled and loans taken by the company paid off. Some other companies’ claims took much longer to be settled; paperwork straggled in years after the fire. Connecticut Fire was settling losses until at least June 1911.

The good faith with which the Hartford insurers paid off their claims in San Francisco was noted by the marketplace-as the companies intended-and by industry watchers. One insurance trade publication remarked that “it is preposterous to assume that individual companies involved for millions of dollars paid their claims in full as adjusted ‘for the advertisement’ or from any other motive than an impelling sense of justice.” [9] Still, it is undeniable that meeting their obligations ensured a good reputation, and that meant good business. A post-San Francisco advertisement for Hartford Fire, for instance, touted the company’s successful involvement (“No other company in one year ever distributed to its policy-holders so vast a sum”) and fostered its desired image as a benevolently reliable insurer.

Though no company could have foreseen the scale of the earthquake-sparked fires, the insurance companies of Connecticut ably fulfilled their responsibilities and proved that they were capable of paying off the largest claims that had ever been made against them. Each survived the 1907 recession, an event partly attributable to the San Francisco disaster. Still, over the course of the 100 years since the Great Fire, only one firm, Hartford Fire (now known as The Hartford), continues to offer property-casualty coverage. The rest of the companies, whether through merger or sale or cessation of coverage, were unable to survive the onslaught of time as well as they once did the “general conflagration” of San Francisco.

Lisa Guernsey is an “insurance brat” with a ferocious love of history who moved to Hartford at age 15. Now living in New York City, she is the copy chief at domino magazine.

Explore!

“What a Disaster!” Fall 2011

Limited Bibliography

Archives of the ACE Group of Companies, Philadelphia.

Best’s Special Report Upon the San Francisco Losses and Settlements of the Two Hundred and Forty-Three Institutions Involved in the Conflagration of April 18-21, 1906. New York: Alfred M. Best Company, 1907.

Gall, Henry R. and William George Jordan. One Hundred Years of Fire Insurance: Being a History of the Aetna Insurance Company, Hartford, Connecticut, 1819-1919. Hartford: Aetna Insurance Co., 1919.

Guatteri, Mariagiovanna, Martin Bertogg, and Andrew Castaldi. A Shake in Insurance History: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. Zurich: Swiss Reinsurance Company, 2005.

Hawthorne, Daniel. The Hartford of Hartford: An Insurance Company’s Part in a Century and a Half of American History. New York: Random House, 1960.

The Messenger. Hartford: Aetna Insurance Group, March-April 1956.

Report of the Special Committee on Settlements Made by Fire Insurance Companies in Connection With the San Francisco Disaster. New York: National Association of Credit Men, 1907.

Smith, Dennis. San Francisco Is Burning: The Untold Story of the 1906 Earthquake and Fires. New York: Viking, 2005.

The Travelers Archives, Hartford.

Whitney, Albert W. ( Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Trustees of the Chamber of Commerce of San Francisco) on Insurance Settlements Incident to the 1906 San Francisco Fire. Pasadena, Calif.: California Institute of Technology, 1972.

Notes

[1] Whitney, pp. 5-6

[2] Whitney, p. 69

[3] Aetna 1919, p. 190

[4] Whitney, p. 31

[5] Hartford 1960, p, 183

[6] Whitney, p. 26

[7] Best’s 1907, p. 37

[8] Best’s 1907, p. 54

[9] Best’s 1907, p. 14