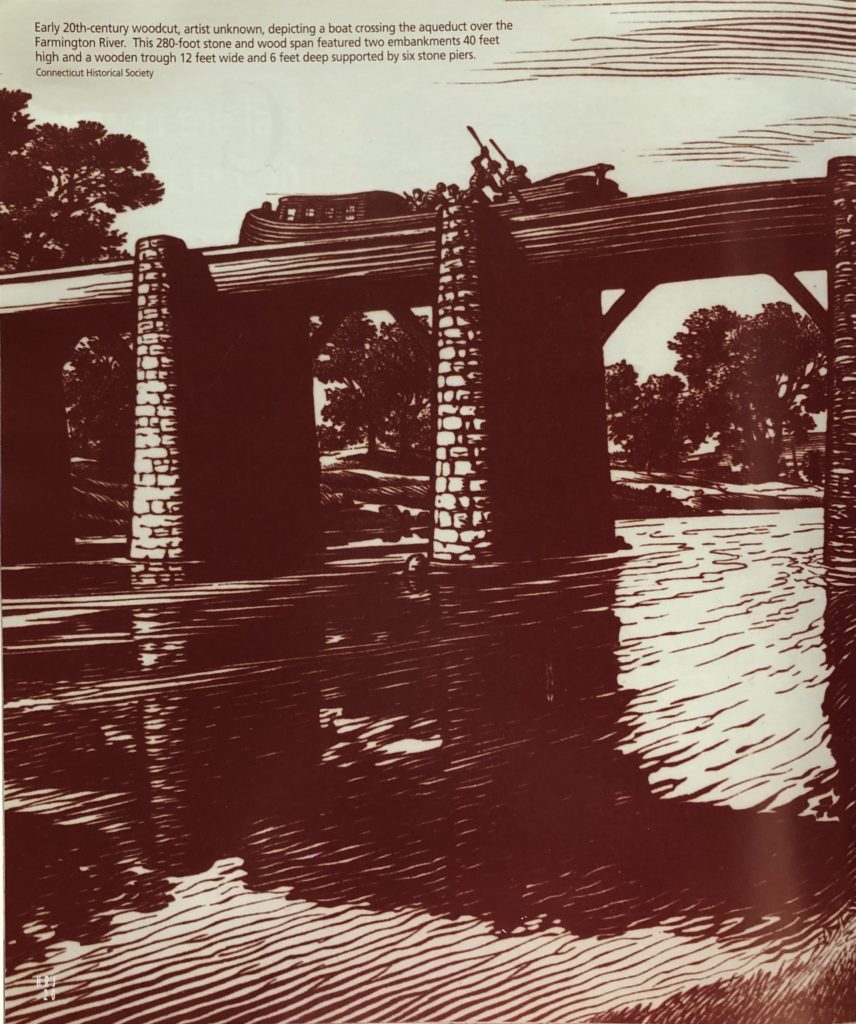

Early 20th century woodcut, artist unknown, showing a boat crossing the aqueduct over the Farmington River. Connecticut Historical Society

By Ellsworth S. Grant

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

It was the largest single transportation project in Connecticut’s history. It would extend from New Haven to Northampton, Massachusetts, and give New Haven a trade connection to northern New England that the city badly needed to compete with its sister capital in Hartford. (Connecticut had two state capitals until 1876.) It brought in the first tidal wave of immigrants from Ireland to dig. Yet, tragically, it failed 20 years after completion.

Canals were a transportation dream of the early Republic. George Washington called them “fundamental to nationhood” and was president of a canal company in Virginia. By 1790 canal companies had been founded in 8 of the original 13 states.

After the second war with England and the end of the Federalist Party, the country experienced an “Era of Good Feeling.” Leaders in Congress favored a protective tariff for manufacturers, a home market, and better transportation. “Let us,” said John Calhoun in 1817, “bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” That same year, New York began construction of the Erie Canal, stretching 363 miles from the Hudson River to Lake Erie. When completed in 1825, it outstripped all eastern seaports as the best route to the Midwest. Recently restored, it is still viable today.

In 1821, New Haven, realizing its port could no longer compete against the thriving towns along the Connecticut River in trading with New England, resolved to survey the country north through Farmington for a canal route. Under the skillful leadership of the lawyer James Hillhouse, representatives from 17 towns met in Farmington the following January and resolved that the project “would afford great convenience, enhance the value of production of the country and enrich the population.” A graduate of Yale in Nathan Hale’s class of 1773, Hillhouse served in Congress during the administrations of Washington and Jefferson; New Haven would remember him best for planting the city’s elms and laying out Grove Street Cemetery. [Readers will recall his role as the state’s first school fund commissioner in “West of Eden,” Summer 2007.]

Ceremonial spade used by Governor Oliver Wolcott at the Farmington Canal’s groundbreaking, July 4, 1825, featuring a portrait of James Hillhouse by William Giles Munson. New Haven Museum

Benjamin Wright, chief engineer of the Erie Canal, was hired to undertake a rough survey and concluded that the proposed route was “favorably formed for a great work of this kind.” The legislature granted a charter of incorporation to the Farmington Canal Company in May 1822. Five commissioners, headed by Judge Simeon Baldwin, were appointed; the others were prominent New Haveners, including the inventor Eli Whitney. They estimated the cost of construction would be half a million dollars, 40 percent of which would be subscribed by the newly formed Mechanics Bank of New Haven. Soon, Massachusetts approved granting a charter in that state that would extend the route from Southwick to Northampton, allowing the canal to reach the Connecticut River. Another New Haven bank put up $100,000 for the Hampshire and Hampden Canal Company, and later the two companies merged. Their investors dreamed of a canal system that would someday even reach the St. Lawrence River in Canada!

Even though New Haven’s elite supplied most of the capital as well as the administration for the canal, the original subscription for 1,000 shares did not meet the expectations of the Canal Committee, a foreboding of trouble ahead. Finally, three years after incorporation, groundbreaking ceremonies took place on July 4, 1825, at Salmon Brook Village in Granby, attracting a crowd of more than 2,000. The New Haven delegates traveled in a canal boat on wheels that was covered with a white awning and flag-decorated curtains and drawn by four horses, which were frequently changed. Oliver Wolcott Jr., Connecticut’s governor, spoke briefly, but another bad omen occurred when the spade he used to break ground broke.

Though Wolcott had shown himself a supporter of economic ventures, especially woolen mills, it is curious that he did nothing to help the canal financially. The state did not offer one dollar’s aid. The reason was the powerful influence of the Hartford-based Connecticut River Company that opposed any competition to its dominance of Connecticut River traffic and was engaged in building a canal around the Enfield Rapids to allow navigation north of Hartford. Certainly, the lack of state money contributed to the Farmington project’s failure.

The Farmington Canal commissioners hired Davis Hurd, an engineer on the Erie Canal, as chief engineer. His design for the 86-mile route called for a trench 4 feet deep, 20 feet across at the bottom, and 36 feet wide at the top. At each side were an embankment to hold the water in and a 10-foot-wide towpath. To accommodate the 292-foot rise between New Haven and Granby, he had to construct 28 wooden locks, each 75 feet long and 12 feet wide. On the outer side a dry wall of heavy stone supported the canal. Stephen Walkly and Leonard Johnson of Southington served as general contractors for building the locks, a task that caused them numerous headaches. Various sections of the canal were built by local contractors.

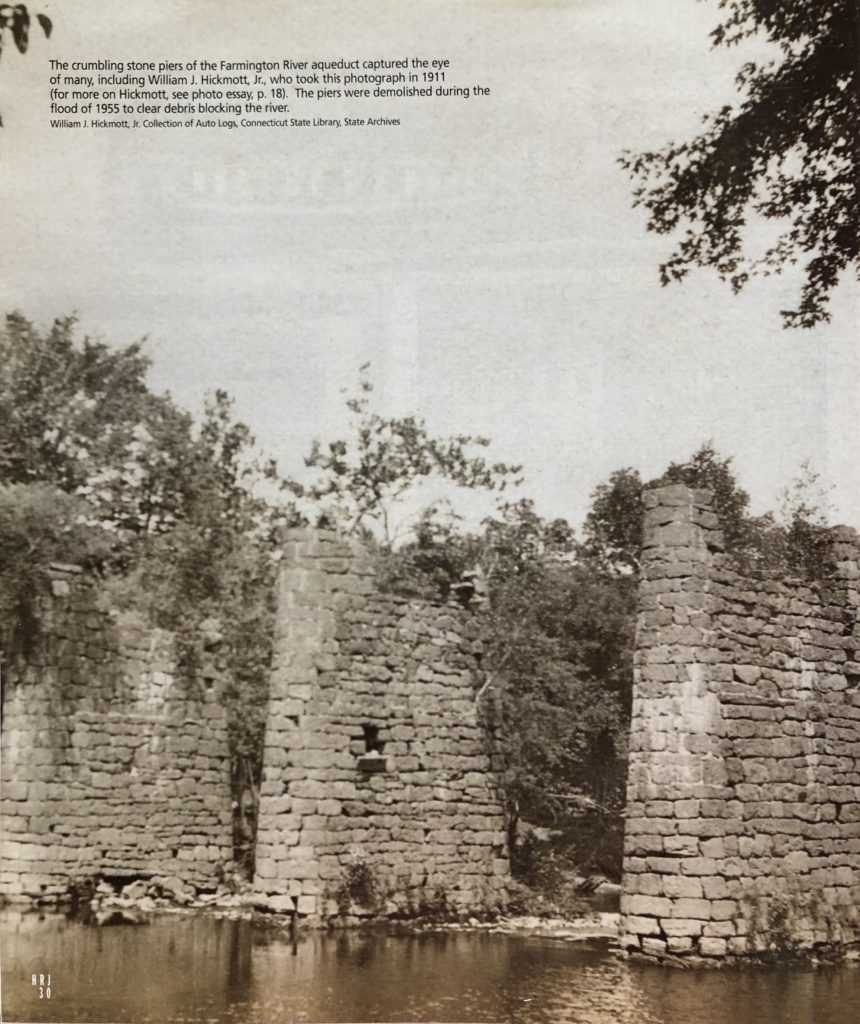

The most challenging engineering feat was the building of aqueducts over the rivers that intersected the canal route. The one crossing the Farmington River was the largest, a 280-foot span of stone and wood. Hurd designed two embankments 40 feet high and a wooden trough 12 feet wide and 6 feet deep supported by six stone piers. The horses that pulled the boats walked across on a towpath next to the trough.

Who would dig the big ditch? Local labor, including the small population of free blacks (especially in the New Haven area) who were able to get work on the canal, was in short supply. The staid Yankee Congregationalists were astonished when 28 gangs of Irish immigrants, armed with picks and shovels, appeared along the proposed route. They labored in crews of 10 to 20 each. Their heavy brogues and rough appearance, coupled with the limitless capacity of some for hard liquor, caused consternation and resentment. When in 1832 a Catholic church was organized in New Haven to serve the Irish Catholics, an editorial in the local paper was headed, “The Pope’s Coming!” The Irish were not welcome; they were objects of distrust and therefore isolated. Hired by contractors and subcontractors on the canal, they were the lowly, nameless diggers. Not only underpaid, the workers (as well as the contractors) were often paid late because of the company’s teetering on insolvency. Sometimes, they were paid in scrip, redeemable at half the paper value.

A folk song the Irish crew loved to sing illustrated their harsh relationship with their employers:

A new foreman was Gene McCanna

By God he was a blaming man

Last week a premature blast went off

A mile in the air went Big Jim Croft.

When next payday came around

Jim Croft was a dollar short. When he

Asked, “What for?” came the reply:

“You were docked for the time

You spent in the sky.”

By the summer of 1826, progress was visible in Farmington, although many residents were unhappy with the location of canal bridges and the construction of embankments. The dispute stopped further work for four months. The Hartford Courant made jibes at New Haven and the canal, calling it “the little ditch.” By June 1828 a feeder canal began bringing water from the Farmington River and the aqueduct to carry the canal over the river was finished. In anticipation of the opening, the first canal boat, named the James Hillhouse in honor of the canal’s superintendent, was launched. Two hundred ladies and gentlemen boarded the boat, which was drawn by three horses over the aqueduct.

The official opening, however, was delayed by heavy rain. On September 4, the embankment gave way and the mouth of the feeder canal damaged. By November all was repaired, and on November 10, the James Hillhouse left New Haven for Farmington carrying 60,000 shingles. Two days later, it rendezvoused in Farmington with the Weatogue coming south from Simsbury with a party of celebrants. The same afternoon, a packet boat from New Haven arrived with passengers and 200 barrels of salt. In the succeeding weeks the canal became busy with New Haven boats hauling commodities such as salt, sugar, molasses, flour, coffee, and hides; they returned with upcountry produce such as apples, cider, butter, and wood.

In 1835 the canal opened all the way to Northampton, Massachusetts. On July 30, the Northampton, using the Hampshire & Hampden Canal in Massachusetts and drawn by five horses at 4 miles per hour, completed the first through journey from Hillhouse Basin in New Haven to the Connecticut River. The 70-mile trip took 24 hours and cost passengers $3.75, including meals. The boat was greeted along the way by cheering crowds and a roaring cannon. When the last stretch was reached, four gray horses took the towline. From the bow of the Northampton, Governor Wolcott waved to the governor of Massachusetts. It seemed like an auspicious beginning.

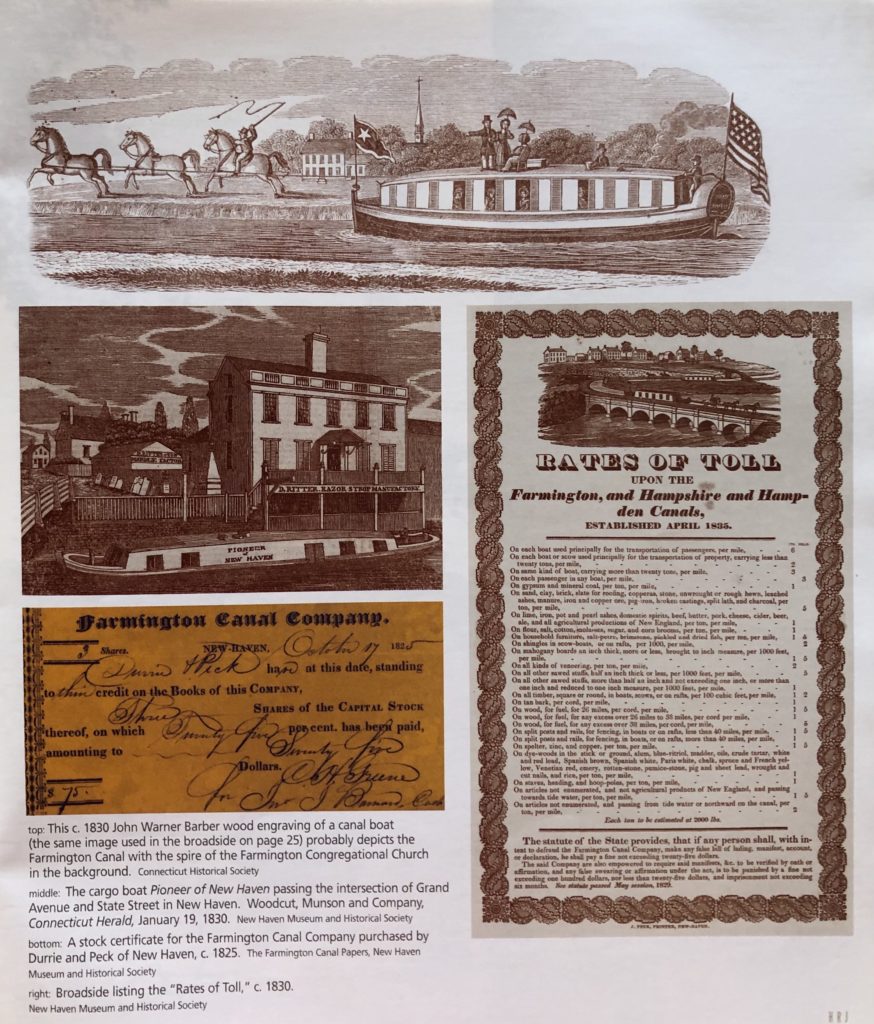

top: John Warner Barber, engraving, c. 1830. Connecticut Historical Society. middle left: The cargo boat “Pioneer of New Haven” at Grand Avenue and State Street, New Haven. Woodcut, Munson and Company, Connecticut Herald, January 19, 1830. New Haven Museum. bottom left: Stock certificate, c. 1825. New Haven Museum. right: broadside, c. 1830. New Haven Museum

But it was not to last. There were still long periods when the canal had to be closed because of breaks and the lack of income for adequate maintenance. Twice the big stone arch carrying it over the Salmon Brook at Granby was washed away. In 1829 very dry weather impeded navigation; the next year, a bad break in the bank occurred, and that fall a drought forced closing a section for three months. Every time there was a break due to flooding, damages had to be paid to the farmers whose fields were inundated. Over a four-year period, the company spent more than four times its total revenue. In the reorganization of 1836, the original investors lost $1 million.

In 1840 Joseph E. Sheffield of New Haven took control. Though still undercapitalized, the canal company did better; its best year, 1844, saw record-breaking tonnage, no days lost, and a good profit, the only one the project ever made. But a severe drought the next July shut down the entire canal for two months.

Already a new and cheaper form of transportation was sealing the canal’s doom, a steam-spouting iron monster that ran on tracks on dry land. Discouraged and fearful of a bleak future, the stockholders in 1846 accepted the inevitable and petitioned the legislature for the right to build a railroad. On January 11, 1848, the year trains began running from New Haven to Plainville, all canal operations ceased.

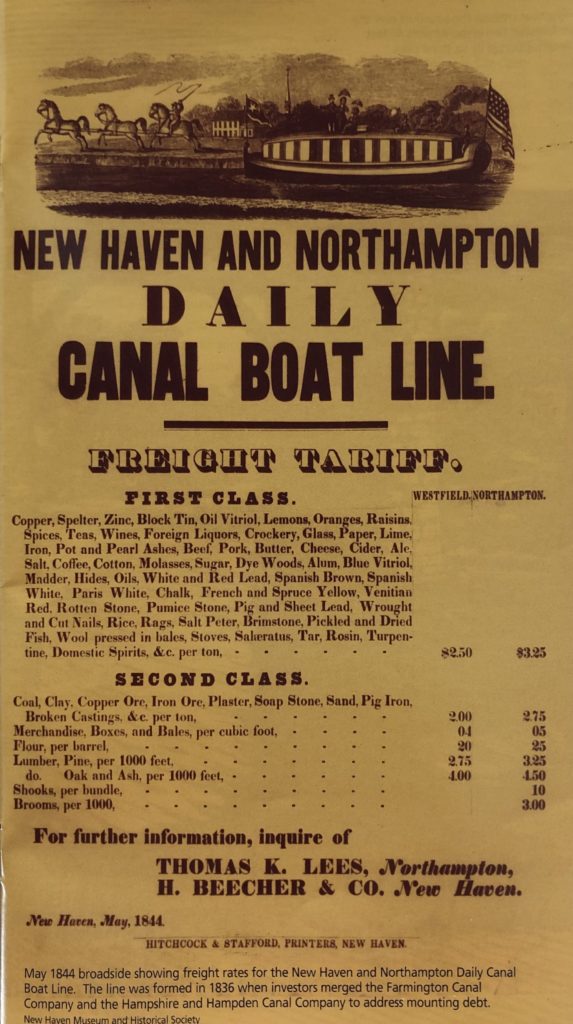

Broadside, May 1844, showing freight rates for the New Haven and Northampton Daily Canal Boat Line. The line was formed in 1836 earn investors merged the Farmington Canal Company and the Hampshire and Hampden Canal Company to address mounting debt. New Haven Museum

During the two decades of its existence, the Farmington Canal greatly stimulated the local economy. Agricultural output and manufactures could be easily and cheaply shipped and likewise imports brought in by merchants. Property values increased along the route. Farmington benefited by shipping wood to New Haven in its own line of boats. On Main Street the Union Hotel was, according to one young traveler, “an impressive sight.” The number of retail stores jumped from 12 to 18. Plainville and Unionville also prospered. As the head of navigation because of the feeder dam and canal, Unionville was able to develop a flourishing industrial center. Recreation was another benefit: in winter there was skating on the canal and in summer swimming. These developments, however, could not obscure the fact that New Haven banks and individual investors had suffered heavy financial losses.

Stone piers of the Farmington Canal aqueduct over the Farmington River, 1911. photo: William J. Hickmott, Jr. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

This story in a slightly shorter version appears in Connecticut Disasters: True Stories of Tragedy and Survival, by Ellsworth S. Grant (Insiders’ Guide: 2006), available at area bookstores. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Globe Pequot Press, www.globepequot.com.

Explore!

Canal Sites to Visit

Statue of William Lanson, one of the contractors that built the New Haven portion of the canal, Canal Street, New Haven. Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, New Haven, 2021. photo: Elizabeth J. Normen

After the canal was abandoned, a rail bed was laid over much of the route. The Canal Railroad then operated well into the 20th century (merging with the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad in the late 1800s). Today, large portions of the rail line have been converted to a trail stretching from New Haven to Northampton, Massachusetts. Large sections are paved for walking and biking. The trail is accessible at many points, and maps are available online. https://fchtrail.org/pages/default.asp.

In Cheshire, the Lock 12 Historical Park, 487 North Brooksvale Road (Route 42), offers a restored section of the canal including a lock, lockkeeper’s house, museum, bridge, and 2.9-mile hiking/biking trail. The park is operated by the Town of Cheshire and is open year-round (the museum is open the first Sunday of every month from noon to 2 p.m., weather permitting.) For more information, call (203) 272-2743 or visit https://www.cheshirect.org/cms/one.aspx?portalId=8580940&pageId=17501652.

Read all of our stories about Connecticut travel & transportation history by clicking on the category link at the top of the page.

CT History for Kids: Read about the Farmington Canal and the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail at Where I Live: Connecticut.

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!