by David Kluczwski

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

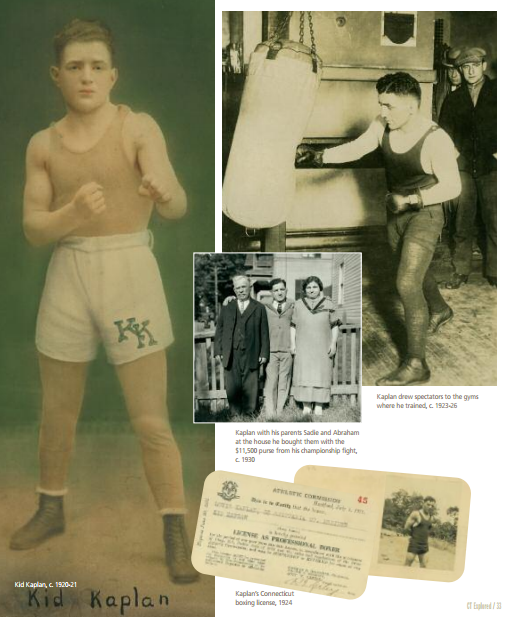

Kaplan came to the United States from Russia at the age of five around 1906 with his family, who settled in Meriden, Connecticut. Life was tough for the young family. His father worked in the junk business, collecting and selling others’ discarded items, and with finances tight Kaplan helped his father by carrying castoff items in sacks on his own back because they could not afford a horse or wagon. Bob Morrisette, a reporter for the Meriden Record Journal, said of Kaplan’s childhood, “Kaplan attended the Willow Street School, but his education went no further than the fifth grade. His first job was peddling fruit for Louis Sheftel, climbing stairs to second-and-third-story-apartments for a wage of 5 cents a day.” Years later, Kaplan’s daughter Rosanne Dolinsky recounted that Kaplan had had no choice but to wear the hand-me-down clothes of his sisters and was often the brunt of ridicule by other children.

Kaplan discovered his ability to fight by accident when a gang of boys framed him for stealing fruit from a vendor’s wagon. After being falsely accused, Kaplan gave the leader of the gang a beating so bad that the policeman who had arrived at the scene to arrest the actual thief recommended that Kaplan try his luck at boxing. Steven A. Riess, author of Sport in Industrial America (Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1995), notes that it was very common for immigrant Jewish youths to encounter conflicts in their neighborhoods as they walked to the park, to school, or in to the neighborhoods of other ethnic groups. Boxing, therefore, was a practical skill for many young immigrant Jews, including Kaplan, to attain. Riess also argued that boxing was appealing because in order to provide additional support to their struggling families, many Jewish boys worked full-or-part-time after school to contribute financially, which made it difficult for them to participate in organized sports such as football and baseball.

Boxing gyms were widely available, notes Allen Bodner in When Boxing was a Jewish Sport (Praeger Trade, 1997), and were often open at all hours of the day and night, especially for those individuals who held full-time jobs or took up work while attending school. Because equipment such as boxing gloves was provided by schools, gyms, and community centers, the sport was affordable for many Jewish youths.

Kaplan took up boxing in 1919 at the Lenox Athletic Club in Meriden, fighting among some local boys he knew. At the time he only owned sneakers, a belt, and a pair of green tights—and needed nothing more. His first fight netted him a total of eight dollars (from whom, we don’t know), and he recalled that only a dollar and a quarter of it remained for him after he gave the rest to his struggling family.

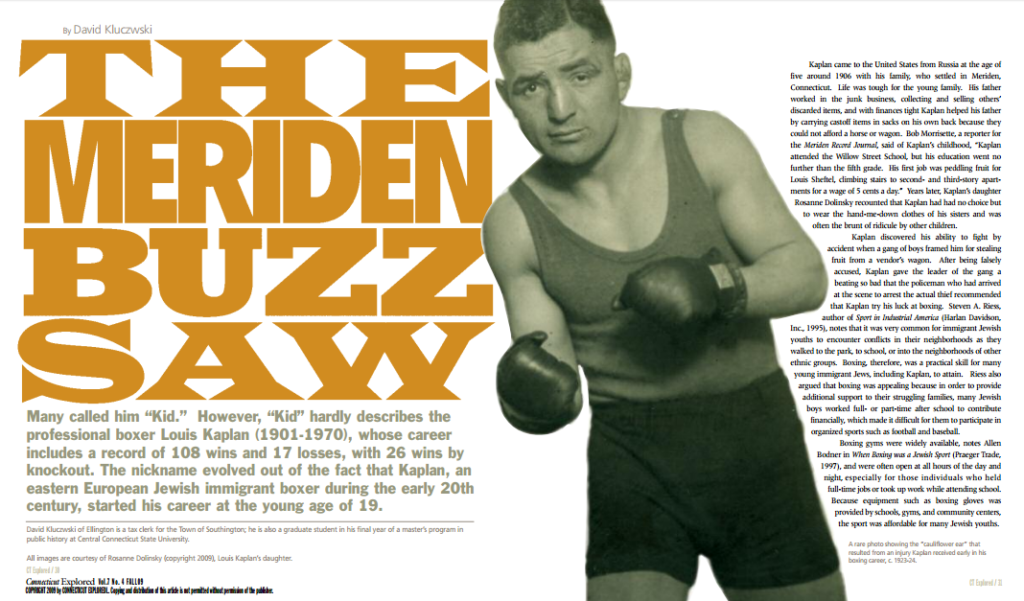

At the Lenox Athletic Club Kaplan met Moe Levine, operator of a pool room and smoke shop who occasionally worked as a sports promoter. Levine knew nothing about the sport of boxing, but he was instrumental in launching Kaplan as a professional boxer. Levine was able to arrange unofficial boxing bouts in New York City for Kaplan, jump starting the young man’s career. In one of these bouts, Kaplan’s ear was mangled; observers called it a “cauliflower ear” because of its new shape. Although a minor injury, it was this slight misfortune that completely transformed Kaplan’s boxing career. Shortly after the fight in which his ear was injured, Kaplan hitchhiked from Meriden to Hartford; a man named Dennis McMahon picked him up. Upon seeing Kaplan’s “cauliflower ear,” McMahon immediately recognized that the boy was a boxer. McMahon, who as an actual boxing promoter knew much more about the sport than Levine did, agreed to buy Kaplan’s contract.

As the ranks of Jewish boxers grew, these athletes became rolemodels in their communities. Riess notes that the skills they exhibited in the ring countered stereotypes that labeled Jews as weak and cowardly. This stereotype was derived, in part, from the fact that many Jewish immigrants worked as either peddlers or tailors, neither of which occupation required much physical strength.

Despite his raw talent, Kaplan did not typify the ideal boxer. He was short in stature, and his arms were short, too, limiting his reach. But whatever Kaplan lacked in physical ability he made up within heart, and soon he earned a new nickname, the “Meriden Buzz Saw.” The name originated from Kaplan’s fighting style, which was characterized by his refusal to stop punching until his opponent wore down. He never turned down an opponent and gave his all in the ring. Kaplan also took his training and preparation for fights to the highest levels in order to beat his best during a fight. Manny Leibert, a long time boxing promoter in Connecticut, told the Jewish Ledger newspaper in 2006 that Kaplan “would run from Hartford to Meriden sometimes just to keep in shape. He would run long distances. Conditioning is very important in boxing. If you are fighting ten rounds, you don’t want to get tired after five rounds and quit.”

Kaplan’s hard training and his determination in the ring led to the crowning a chievement of his boxing career, the world feather weight championship of the world in 1925. On January2, with more than 2,000 friends from Meriden in the crowd, Kaplan took on Danny Kramer of Philadelphia for the championship at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The Meriden Daily Journal reported that it took Kaplan only 9 rounds out of 15 to defeat Kramer and win the title. His proud parents were in the audience. At a celebration in their home the day after her son’s victory, his mother Sadie told the Meriden Morning Record, “I am the happiest woman in the world, I want to thank Meriden for all it has done for my boy. I am so pleased with the reception, the fine way they treated him Saturday night. Everything was wonderful. And, Louie’s my boy. That explains everything. No further statement is necessary.”

Pride was not all he provided his parents. Kaplan used the $11,500 he earned from the championship bout to buy them a home. He also bought a horse and wagon to lighten the workload for his father, who still was hauling junk.

As early 20th-century Jewish boxers such as Kaplan accumulated wealth and status, many encountered organized crime. Peter Levine in Ellis Island to Ebbets Field (Oxford University Press, 1992) notes that Barney Ross, a Jewish boxer from Chicago, often saw Al Capone and his mob at his fights. Although it was never proven whether Ross fixed any of his bouts for Capone and his gang, such shady characters frequented Ross’s matches (and those of other prominent Jewish boxers such as Ruby Goldstein, Abe Attell, and Benny Leonard) and placed bets on the outcome. The mob’s interest in boxing did nothing to enhance the sport’s credibility as a career choice. While many boxers caved to organized crime’s demands, accepting money and other perks in exchange for throwing fights, others—including Kaplan—were able to resist.

As early 20th-century Jewish boxers such as Kaplan accumulated wealth and status, many encountered organized crime. Peter Levine in Ellis Island to Ebbets Field (Oxford University Press, 1992) notes that Barney Ross, a Jewish boxer from Chicago, often saw Al Capone and his mob at his fights. Although it was never proven whether Ross fixed any of his bouts for Capone and his gang, such shady characters frequented Ross’s matches (and those of other prominent Jewish boxers such as Ruby Goldstein, Abe Attell, and Benny Leonard) and placed bets on the outcome. The mob’s interest in boxing did nothing to enhance the sport’s credibility as a career choice. While many boxers caved to organized crime’s demands, accepting money and other perks in exchange for throwing fights, others—including Kaplan—were able to resist.

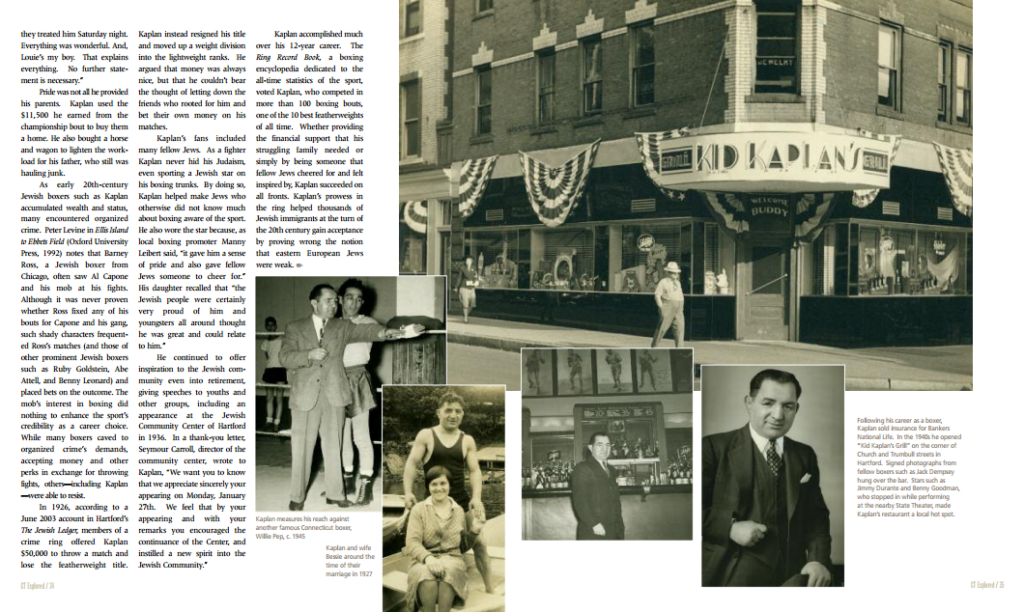

In 1926, according to a June 2003 account in Hartford’s The Jewish Ledger, members of a crime ring offered Kaplan $50,000 to throw a match and lose the feather weight title. Kaplan instead resigned his title and moved up a weight division in to the light weight ranks. He argued that money was always nice, but that he couldn’t bear the thought of letting down the friends who rooted for him and bet their own money on his matches.

Kaplan’s fans included many fellow Jews. As a fighter Kaplan never hid his Judaism, even sporting a Jewish star on his boxing trunks. By doing so, Kaplan helped make Jews who otherwise did not know much about boxing aware of the sport. He also wore the star because, as local boxing promoter Manny Leibert said, “it gave him a sense of pride and also gave fellow Jews someone to cheer for.” His daughter recalled that “the Jewish people were certainly very proud of him and youngsters all around thought he was great and could relate to him.”

He continued to offer inspiration to the Jewish community even in to retirement, giving speeches to youths and other groups, including an appearance at the Jewish Community Center of Hartford in 1936. In a thank-you letter, Seymour Carroll, director of the community center, wrote to Kaplan, “We want younto know that we appreciate sincerely your appearing on Monday, January 27th. We feel that by your appearing and with your remarks you encouraged the continuance of the Center, and instilled a new spirit in to the Jewish Community.”

Kaplan accomplished much over his 12-year career. The Ring Record Book, a boxing encyclopedia dedicated to the all-time statistics of the sport, voted Kaplan, who competed in more than 100 boxing bouts, one of the 10 best featherweights of all time. Whether providing the financial support that his struggling family needed or simply by being someone that fellow Jews cheered for and felt inspired by, Kaplan succeeded on all fronts. Kaplan’s prowess in the ring helped thousands of Jewish immigrants at the turn of the 20th ce

ntury gain acceptance by proving wrong the notion that eastern European Jews were weak.