small inset: The Lincoln-type milling machine perfected by Francis A. Pratt that became the industry standard. Museum of Connecticut History

By Ellsworth Grant

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. May/Jun/Jul 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

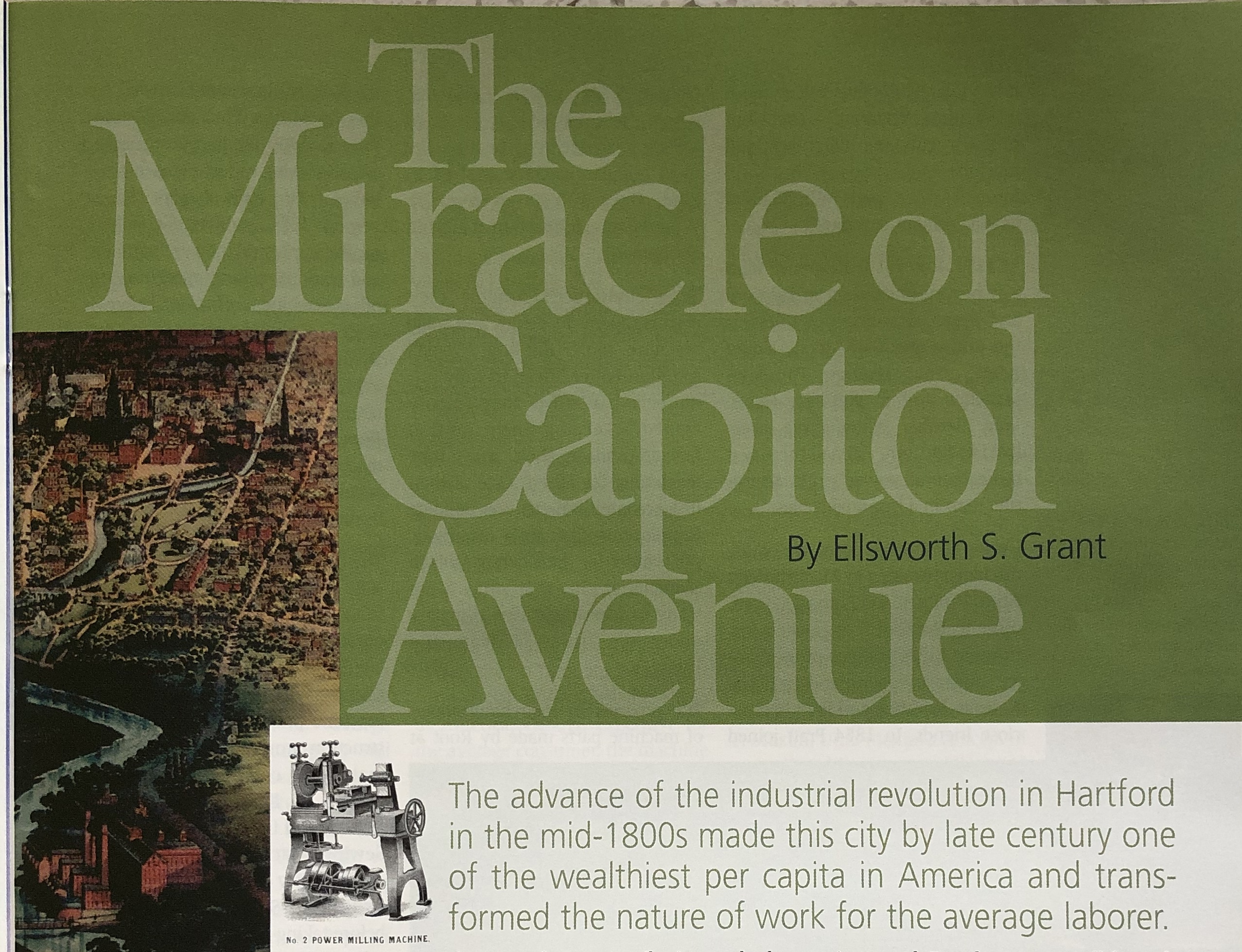

The advance of the industrial revolution in Hartford in the mid-1800s made this city by late century one of the wealthiest per capita in American and transformed the nature of work for the average laborer.

The rise of manufacturing, particularly the incorporation of interchangeable parts and use of special purpose machinery, changed the labor landscape irrevocably. It was a period of rapid innovation and new product development set in a large-scale factory setting. The period also saw a dramatic influx of immigrants to work in the expanding factories.

Though gun manufacturer Samuel Colt has generally been acclaimed as the leader of manufacturing in Hartford during the mid-19 th century, in fact, there were many others contributing to the burgeoning industrial base. While the Colt Armory’s mass production techniques made him a leading gun maker and he proved himself a marketing genius, Colt’s achievements in mass production did not rival those of the factories that thrived along Rifle Avenue , as Hartford ‘s Capitol Avenue was then named, especially after the Civil War.

Long before the building of the State Capitol, even before the completion of the Colt Armory, another entrepreneur was making rifles in the pasture land between Laurel and Broad streets parallel to the Little or Hog River . The success of Christian Sharps’ gun factory was responsible for the Rifle Avenue name and also the catalyst for a succession of businesses that made Hartford a center of metalworking-and renowned for the skill of its machinists-for a hundred years.

Sharps designed a breech-loading rifle that was destined to become one of the most famous single-shot firearms. It was possible to load and fire it five times a minute. During the Civil War some 100,000 Sharps rifles and carbines replaced the old muzzle loaders. Sharps first took his inventions to Robbins & Lawrence in Windsor , Vermont , a small but premier gun manufacturer and machine tool company that soon found it lacked space to fulfill all of its government contracts.

In 1851, Robbins & Lawrence built a two-story brick plant in Hartford and began churning out rifles for the British and later for the Union Army. The famous Brooklyn preacher and abolitionist, Henry Ward Beecher, whose three sisters lived in Hartford , claimed there was more “moral power” in a Sharps rifle than in a hundred Bibles.

During these same years two young machinists working in Massachusetts , Amos Whitney and Francis A. Pratt, came to Hartford to seek their fortunes in Colt’s “college of mechanics” under its superintendent Elisha K. Root. Whitney and Pratt became close friends. In 1854 Pratt joined George S. Lincoln & Company, where he improved a screw-fed milling machine that became the most popular machine tool of its kind. Over 100,000 were built. Whitney soon joined him at Lincoln & Company.

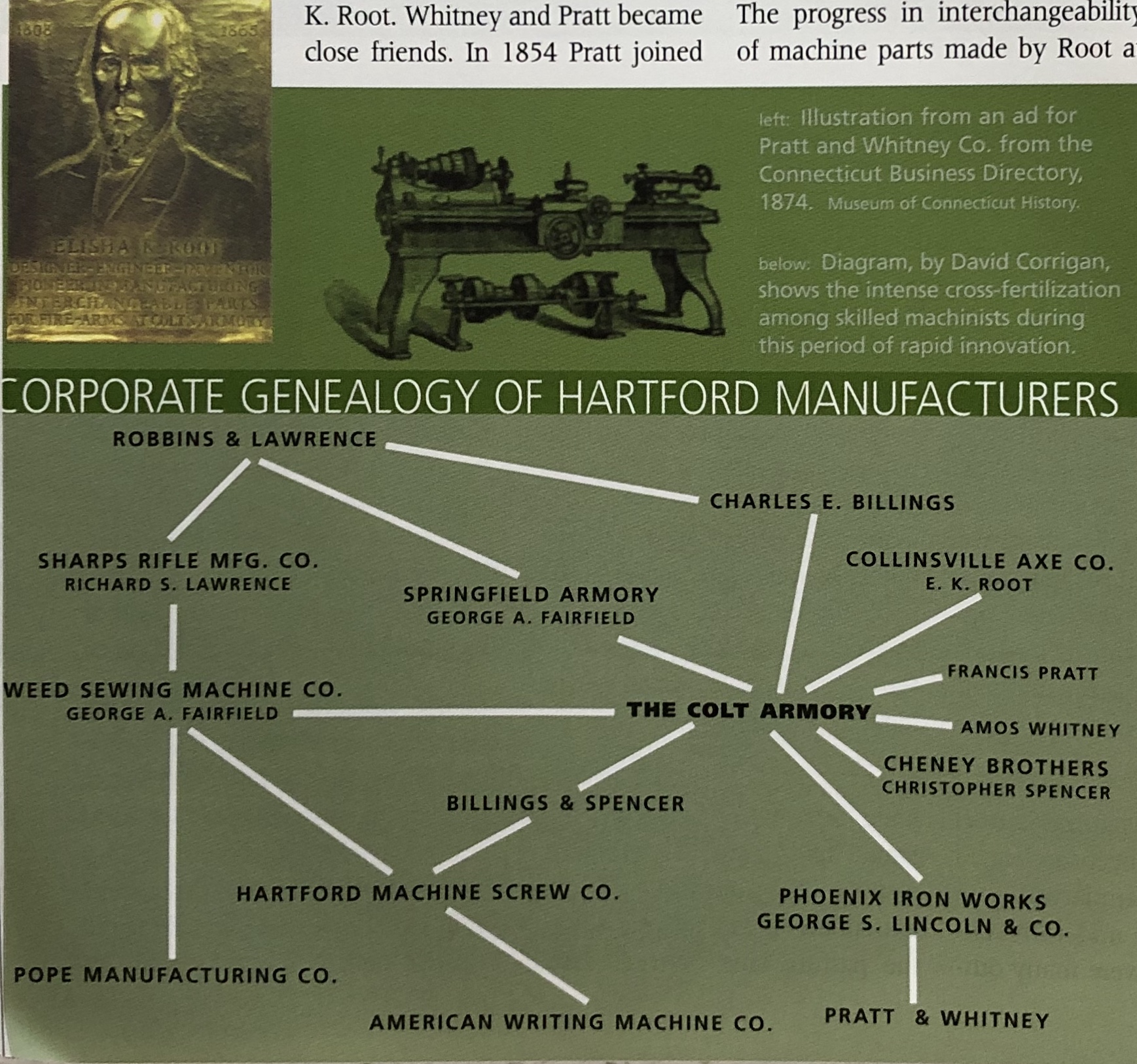

Top left: Elisha K. Root of Colt Manufacturing, mentor to many machinists who later went on to contribute to the manufacturing miracle on Capitol Avenue. Museum of Connecticut History.

They envisioned founding their own company to design and build machine tools. Renting a small room on Potter Street , its only furniture a coal stove, they “moonlighted,” keeping their jobs at Lincoln and in their spare time machining for others. One of their first accomplishments was building Christopher Spencer’s automatic silk winder for the Cheney Mills in Manchester . In 1860 they were ready to form their own company under the name of Pratt and Whitney.

The progress in interchangeability of machine parts made by Root at the Colt Armory was extended further by Messrs. Pratt and Whitney. Prior to 1900 the partners designed an astonishing variety of machines-lathes, boring mills, shapers, planers, vertical drills, grinders, die sinkers, profilers, presses, power hammers, and various cutting machines. No other machine tool builder, before or since, could match this record. Before World War I, Pratt and Whitney Machine Tool was the largest company of its kind. Like Root, Whitney also excelled in teaching hundreds of apprentices to become journeymen and start other businesses.

The first new industry to emerge on Rifle Avenue after the Civil War was Weed Sewing Machine Company. It obtained the patent rights of the late Theodore. E. Weed of Fairfield, Connecticut, inventor of a sewing machine prized for its simple construction and ease of operation, making it competitive with the designs of Elias Howe (1846), Allen B. Wilson, and Isaac Singer. The Weed Sewing Machine Company took over empty space in the now-struggling Sharps Rifle factory before taking over the entire factory when Sharps failed in 1870. Its most popular model was designed by George A. Fairfield, the superintendent of the company.

The invention of the sewing machine was the third stage in the evolution of mass production after the principles of interchangeability were applied to clocks and guns. The Weed Company played a major role in making Hartford one of three machine tool centers in New England and even outranked the Colt Armory in size if not fame. Weed eventually was the birthplace of both the bicycle and automobile industries.

In 1876 Hartford Machine Screw was granted a charter “for the purpose of manufacturing screws, hardware and machinery of every variety.” The basis for its incorporation was the epochal invention of the first single-spindle automatic screw machine. For its next four years the new firm occupied one of Weed’s buildings, milling thousands of screws daily on over 50 machines. Its president was the same George Fairfield who ran Weed and its superintendent was Christopher Spencer, arguably Connecticut ‘s most versatile inventor. Soon Hartford Machine Screw outgrew its quarters and built a new factory adjacent to Weed, where it would remain until 1948.

With the opening of the new Capitol Building in 1878, the name Rifle Avenue was replaced by Capitol Avenue . Under George Fairfield the Weed Company still flourished as the second largest employer in the city. Then occurred a fortuitous meeting that revolutionized its culture. The chain of events began at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, where Colonel Albert A. Pope of Boston saw for the first time that strange two-wheeled contraption with an enormous front wheel and solid rubber tire. Only England made the “penny farthing” bicycle, which was touted as being twice as fast as a horse. But the public disdained this new technology, horses were frightened by it, and municipal ordinances banned it from parks and avenues.

Pope, however, was fascinated. Convinced the bicycle could be a useful and profitable product, he organized the Pope Manufacturing Company in Boston and looked for a contractor with skilled machinists. In the spring of 1878 he approached George Fairfield, then the largest machinery builder for Colt’s Armory. On this occasion Pope brought his prototype, riding it from the railroad station to the Weed factory, followed by scores of wide-eyed youngsters. Fairfield caught the Bostonian’s enthusiasm and convinced a reluctant board of directors to accept an order for 50 bicycles.

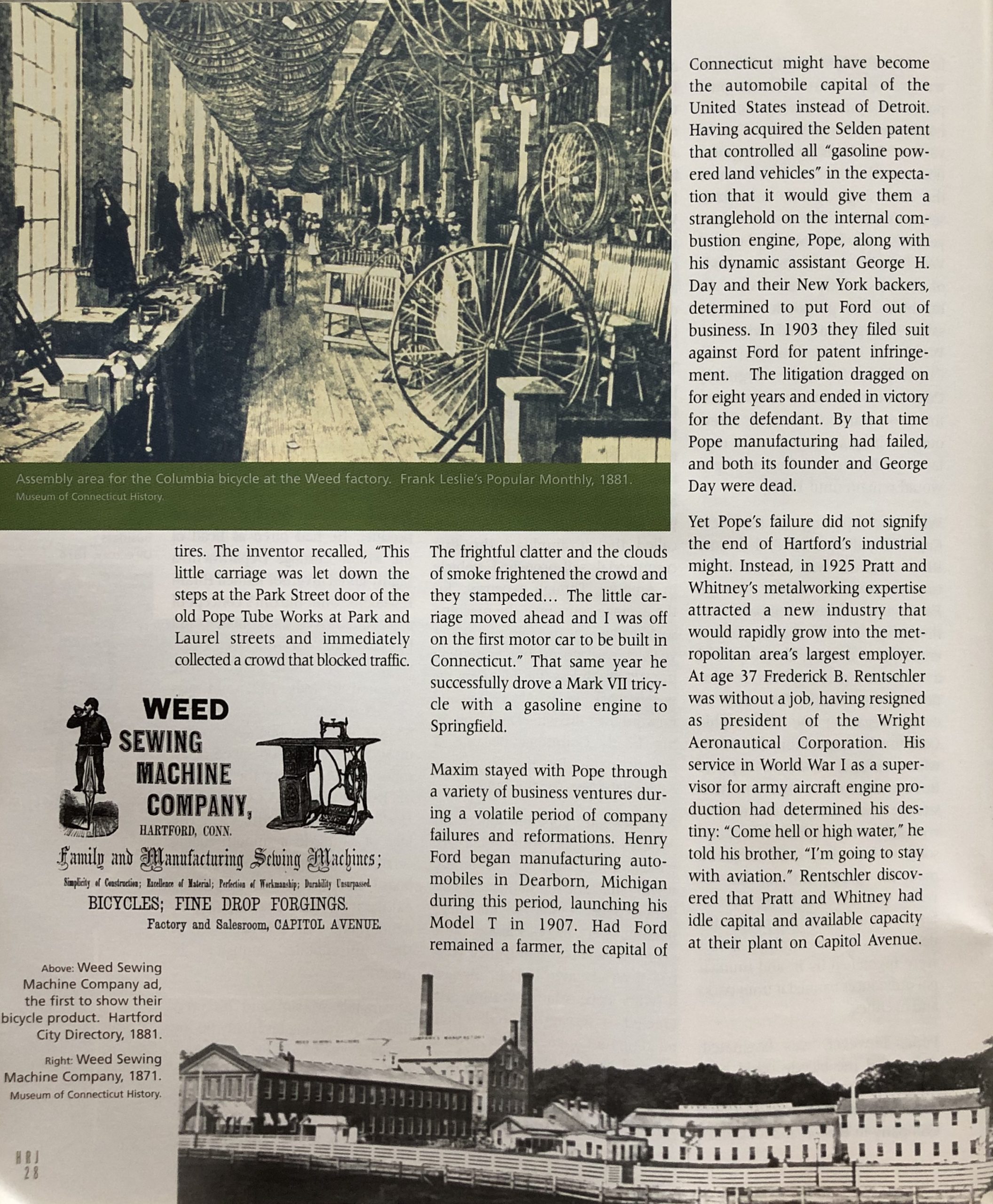

The directors’ reluctance was well-placed. Weed encountered one difficulty after another: learning to forge the head, proper shaping of the wheel rims so as to hold the tires, fabricating steel handle bars and cranks. Weighing in at 60 pounds, the production version was called the ” Columbia ,” the first commercial self-propelled vehicle in America . Though expensive for the average consumer, the machine sold readily-at the rate of 1,000 a year. It was sturdy but extremely hazardous. Unless the rider kept his weight back, he would be pitched forward over the wheel and land on his head. Columbia became a generic name for the bicycle as Kodak later was for the camera.

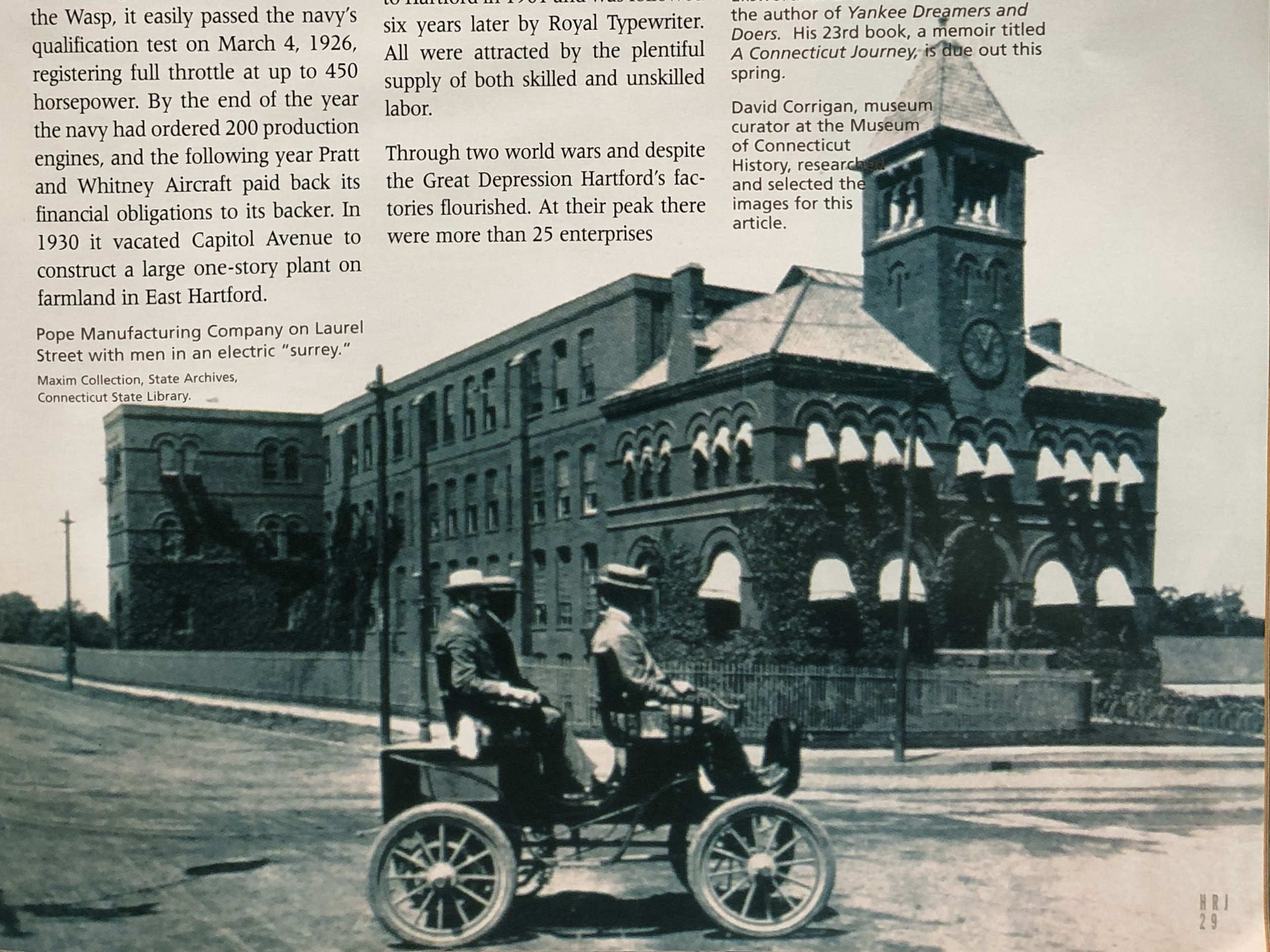

A decade later Pope introduced his “safety” version, with equal-size wheels and chains. By 1890, the sewing machine market having collapsed, Weed employed 600 men making safety bicycles alone. Nine years earlier Pope had gained control of Weed and in 1891 he merged it with Pope Manufacturing. He erected a cream-colored office building on Capitol Avenue , with a paneled apartment for himself on the top floor, and moved his staff from Boston . New production methods were introduced for making pedals, hubs, spokes, and other parts. Pope set up the first metallurgical laboratory in New England . At its peak the Pope complex occupied 18 acres of factory space. Nearly 4,000 employees turned out 50,000 bicycles a year.

Emulating the paternalism of Sam Colt a generation earlier, Pope provided nearby housing and recreation for his workers. Columbia Street and Park Terrace were laid out and filled with attractive nine-room homes. He also gave 75 acres to the south of the factory for the creation of Pope Park .

Unfortunately the bicycle fad peaked by 1896 and collapsed in1900. Desperate to save his empire, Pope focused on developing a new product. He had hired as head of the Motor Carriage Department a highly gifted inventor named Hiram Percy Maxim. Until Maxim’s concept of a gasoline-driven automobile could be perfected, Pope built electric carriages. The Mark III electric appeared in May 1897 and was offered to the public at a price of $3,000. It had an operating radius of 30 miles and a top speed of 12 miles an hour. Under the headline of “HORSELESS ERA COMES,” the Hartford Courant enthused: “The idea of sitting in a smooth rolling carriage, nothing front of the dashboard but space. is something exhilarating and fascinating.” Its debut marked the real beginning of the automobile industry in America .

Meanwhile Maxim and his crew had been working feverishly on the gasoline engine. They installed a three-cylinder version in a Crawford runabout, the most advanced style of carriage, with ball-bearing wheels and rubber tires. The inventor recalled, “This little carriage was let down the steps at the Park Street door of the old Pope Tube Works at Park and Laurel streets and immediately collected a crowd that blocked traffic. The frightful clatter and the clouds of smoke frightened the crowd and they stampeded. The little carriage moved ahead and I was off on the first motor car to be built in Connecticut .” That same year he successfully drove a Mark VII tricycle with a gasoline engine to Springfield .

Meanwhile Maxim and his crew had been working feverishly on the gasoline engine. They installed a three-cylinder version in a Crawford runabout, the most advanced style of carriage, with ball-bearing wheels and rubber tires. The inventor recalled, “This little carriage was let down the steps at the Park Street door of the old Pope Tube Works at Park and Laurel streets and immediately collected a crowd that blocked traffic. The frightful clatter and the clouds of smoke frightened the crowd and they stampeded. The little carriage moved ahead and I was off on the first motor car to be built in Connecticut .” That same year he successfully drove a Mark VII tricycle with a gasoline engine to Springfield .

Maxim stayed with Pope through a variety of business ventures during a volatile period of company failures and reformations. Henry Ford began manufacturing automobiles in Dearborn , Michigan during this period, launching his Model T in 1907. Had Ford remained a farmer, the capital of Connecticut might have become the automobile capital of the United States instead of Detroit . Having acquired the Selden patent that controlled all “gasoline powered land vehicles” in the expectation that it would give them a stranglehold on the internal combustion engine, Pope, along with his dynamic assistant George H. Day and their New York backers, determined to put Ford out of business. In 1903 they filed suit against Ford for patent infringement. The litigation dragged on for eight years and ended in victory for the defendant. By that time Pope manufacturing had failed, and both its founder and George Day were dead.

Yet Pope’s failure did not signify the end of Hartford ‘s industrial might. Instead, in 1925 Pratt and Whitney’s metalworking expertise attracted a new industry that would rapidly grow into the metropolitan area’s largest employer. At age 37 Frederick B. Rentschler was without a job, having resigned as president of the Wright Aeronautical Corporation. His service in World War I as a supervisor for army aircraft engine production had determined his destiny: “Come hell or high water,” he told his brother, “I’m going to stay with aviation.” Rentschler discovered that Pratt and Whitney had idle capital and available capacity at their plant on Capitol Avenue . He singled out a four-story building that had been occupied by the defunct Pope-Hartford Automobile Company. His ambition was to make a radial, air-cooled aircraft engine that would surpass anything yet built. A few days later he got a favorable answer from Pratt and Whitney’s general manager, $250,000 in startup money, and use of the company name.

Initially Rentschler chose only six men to work with him, including two brilliant engineers named George Mead and Andrew Willgoos. In just a few months the first experimental engine was assembled. Called the Wasp, it easily passed the navy’s qualification test on March 4, 1926, registering full throttle at up to 450 horsepower. By the end of the year the navy had ordered 200 production engines, and the following year Pratt and Whitney Aircraft paid back its financial obligations to its backer. In 1930 it vacated Capitol Avenue to construct a large one-story plant on farmland in East Hartford .

Initially Rentschler chose only six men to work with him, including two brilliant engineers named George Mead and Andrew Willgoos. In just a few months the first experimental engine was assembled. Called the Wasp, it easily passed the navy’s qualification test on March 4, 1926, registering full throttle at up to 450 horsepower. By the end of the year the navy had ordered 200 production engines, and the following year Pratt and Whitney Aircraft paid back its financial obligations to its backer. In 1930 it vacated Capitol Avenue to construct a large one-story plant on farmland in East Hartford .

Like birds flocking together, the three industrial giants on Capitol Avenue-Hartford Machine Screw, Pope Manufacturing, and Pratt and Whitney Machine Tool-were surrounded south and west by their satellites and other manufacturers: Billings & Spencer, specializing in drop forging; Hartford Rubber Works, which pioneered the pneumatic tire in 1889; Gray Pay Station Telephone Company, founded by William Gray, who had been trained at Pratt and Whitney; Arrow, Hart & Hegeman, which made electric switches; and two typewriter companies. Underwood Typewriter moved to Hartford in 1901 and was followed six years later by Royal Typewriter. All were attracted by the plentiful supply of both skilled and unskilled labor.

Through two world wars and despite the Great Depression Hartford’s factories flourished. At their peak there were more than 25 enterprises employing more men and women than all the insurance companies and banks together. By the 1960s however, the service sector dominated the economy, and one by one the factories were shut down, merged, or moved to the suburbs.

Today, none of the incubators of the miracle on Capitol Avenue remain. They accounted for the progression of mass production from guns to sewing machines to machine tools to bicycles to automobiles and, finally, to jet aircraft engines. It would be hard to match that record of entrepreneurial ingenuity anywhere, at anytime.

Ellsworth S. Grant was an historian and the author of Yankee Dreamers and Doers. His 23rd book, a memoir titled A Connecticut Journey, was published in 2004.

David Corrigan, museum curator at the Museum of Connecticut History, researched and selected the images for this article.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut companies on our Made in Connecticut Topics page.