(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2016

Over the course of a nearly 40-year career, from 1934 to 1972, New Haven’s J. Edward Slavin was bent on deterring youth at risk from a life of crime. During his first year as New Haven County high sheriff—deep in the Great Depression—he formulated an ambitious and innovative plan using a club, a movie, comic books, and a “Jail on Wheels” to reach young people.

“Jack” Slavin became high sheriff of New Haven County in 1935. His responsibilities included overseeing the New Haven County Jail and selecting grand juries. Slavin believed that if he could intervene early enough in the lives of at-risk boys and girls they would become good, law-abiding citizens instead of law-breaking criminals who were an expense to society. Slavin, quoted in the Waterbury Republican (July 23, 1944), said, “Do you know that we in America have the largest jail and prison population in the world? That proves we didn’t spend money in the right place. We spent it at the top, creating large police departments and other agencies for the prevention of crime and enforcement of law and order, while we neglected the bottom where crime starts.”

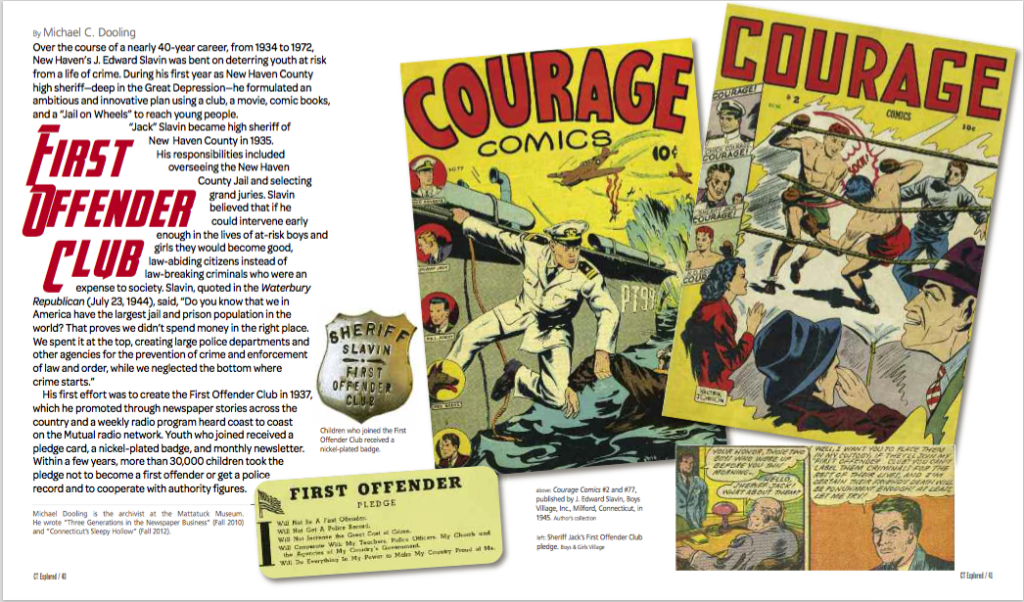

His first effort was to create the First Offender Club in 1937, which he promoted through newspaper stories across the country, and a weekly radio program heard coast to coast on the Mutual radio network. Youth who joined received a pledge card, a nickel-plated badge, and monthly newsletter. Within a few years, more than 30,000 children took the pledge not to become a first offender or get a police record and to cooperate with authority figures.

Slavin also envisioned a home where troubled boys could live, work, and learn as a way to redirect their energies away from a life of crime. He was inspired by the success of a residential program in Nebraska founded by Father Edward J. Flanagan in 1917. By 1940 Father Flanagan’s Home for Boys had grown into a fully functioning community known as Boys Town and located about 10 miles outside of Omaha.

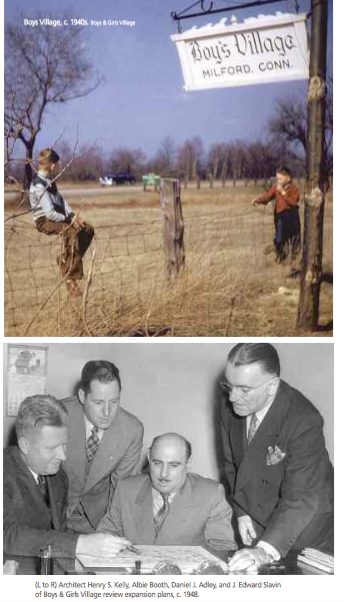

Slavin was the first president of his version of Boys Town, to be called Boys Village, and surrounded himself with people who could help fulfill his dream. The board of directors was composed of successful men from diverse fields, including William F. Hayes, former chief jailer for New Haven County, as vice president, Yale football legend Albert “Albie” Booth as treasurer, and home builder Peter Juliano as secretary. Other members of the board included Stanley Komykowski, a prominent 4-H member who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and trucking company magnate and former New Haven Police Commissioner Daniel J. Adley.

Slavin considered purchasing Charles Island off the coast of Milford in 1938 as a site for his Boys Village. The Dominican religious order had used the island as a retreat center since 1929. Slavin negotiated with the Dominican Fathers, and on September 19, 1938, The New York Times reported that Slavin had announced his intent to purchase the facility. The deal was never consummated, though. Events two days later undermined the deal, as the great New England hurricane of 1938, with sustained winds of more than 90 miles per hour and 14- to 18-foot tides, delivered devastating damage to the retreat buildings. Slavin withdrew his offer.

In 1941 Slavin and his associates acquired 82 acres off Wheelers Farms Road in Milford. Boys Village was established the following year, and its doors opened in 1944. It initially operated as a summer camp and became a year-round facility in 1947. With a 14-room farmhouse, small cottage, cornfield, potato patch, dairy barn, and poultry buildings, it was originally designed to accommodate 16 boys who were 10 years old and older. Patterned after a New England village, it offered communal living, educational and training facilities for industry and farming, and a psychological clinic. The boys grew most of the food they ate and were responsible for performing chores around the facility. In 1948 the board of directors made plans to accommodate a total of 31 boys.

The project was not without its critics. Neighbors expressed concerns about bringing what they perceived as undesirable elements into their neighborhood. Some of the boys would be attending Milford public schools, posing a potential burden on taxpayers. Slavin defended his effort in The Hartford Courant (January 2, 1942) by pointing out that his facility would be “…neither a penal institution nor a reform school. The fair-minded citizens of Milford, where I have been a resident and voter for nearly a quarter of a century, I believe, have confidence enough in me and know me well enough to know that I would not bring anything to Milford that would not be an asset to that beautiful town.”

The project was not without its critics. Neighbors expressed concerns about bringing what they perceived as undesirable elements into their neighborhood. Some of the boys would be attending Milford public schools, posing a potential burden on taxpayers. Slavin defended his effort in The Hartford Courant (January 2, 1942) by pointing out that his facility would be “…neither a penal institution nor a reform school. The fair-minded citizens of Milford, where I have been a resident and voter for nearly a quarter of a century, I believe, have confidence enough in me and know me well enough to know that I would not bring anything to Milford that would not be an asset to that beautiful town.”

The farm/village concept of teaching and reforming young people was not a new one. Since the early 19th century, juveniles who had scrapes with the law had been incarcerated alongside adult criminals butthe public realized the need for a better means of dealing with such children and began to petition the state legislature.

The first farm school in the United States was organized in 1833 on Thompson’s Island in Boston Harbor. The Boston Farm School served “at-risk” boys—mostly orphans and indigents. The boys were given academic instruction and taught agricultural skills and other useful trades. The juvenile reform movement in Connecticut began in 1851 when the Connecticut General Assembly established the first state reform school. Under this act, boys younger than 16 who committed an imprisonable offence could be sent to the reform school instead of to adult jails. The school opened in 1854 in Meriden.

The central-school concept at the reform school gave way to a cottage concept in 1880 when the legislature funded the first cottage on the grounds; more cottages followed during the next few years. The school (renamed the Connecticut School for Boys in 1893) provided education, devotional exercise, recreation, and chores that supported that facility. As time went on, vocational trades were taught to the boys so they would have work skills when they left.

A privately-funded effort was the Watkinson Farm School, created in Hartford in 1881 to carry out the wishes in the will of benefactor David Watkinson to provide “relief, protection, instructions, reformation and employment of children between the ages of 6 and 21.” Watkinson helped lead private philanthropy in creating more humane reform measures for wayward youth. Helen Worthington Roger notes in her “History of the Movement to Establish a State Reformatory for Women in Connecticut” (Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Winter 1929) that since at least the 1860s reformers had been pressuring the state to move children and women convicted of lesser crimes out of jails and prisons and into reform settings.

The adoption of reform facilities for delinquent girls paralleled that for the boys. Connecticut Industrial School for Girls was established in Middletown in 1868 as a private institution that believed that, as Mark Jones notes in The Connector (Connecticut State Library, November 2002), “the best place for [delinquent]girls was on a country farm far away from what they believed was crime, filth, and degradation of the city.” The school was built with a cottage plan meant to mimic a family structure. It became a state institution in 1921. The state changed the school’s name to Long Lane Farm in 1921 and to Long Lane School in 1943. [See “Remaking Wayward Girls,” Summer 2003].

By the 1940s cottage-style living, classroom education, vocational training, religious involvement, recreational activities, and working at the facility had been established as the accepted mode of reforming less-violent juvenile delinquents.

Slavin thus joined a long tradition of private efforts to improve the lot of vulnerable youth, taking his place among those who felt the state’s system did not offer youths much of a chance. He also hoped to catch young people before they fell into the court system. Slavin’s oft-stated goal was “to provide a village of opportunity for the homeless boy, where he may develop a spirit of self respect, a love for work, and a desire to forge ahead through honest industry. … I really believe all boys have good in them if they are shown the right way. I always believed that if you keep a boy busy he won’t get into trouble. I’m not interested in how much it costs to grow a boy. I’m interested in what kind of boy he’ll make.” He spelled out in Boys’ Village: A Home for Homeless Boys (1943) the goals of Boys Village:

Slavin thus joined a long tradition of private efforts to improve the lot of vulnerable youth, taking his place among those who felt the state’s system did not offer youths much of a chance. He also hoped to catch young people before they fell into the court system. Slavin’s oft-stated goal was “to provide a village of opportunity for the homeless boy, where he may develop a spirit of self respect, a love for work, and a desire to forge ahead through honest industry. … I really believe all boys have good in them if they are shown the right way. I always believed that if you keep a boy busy he won’t get into trouble. I’m not interested in how much it costs to grow a boy. I’m interested in what kind of boy he’ll make.” He spelled out in Boys’ Village: A Home for Homeless Boys (1943) the goals of Boys Village:

- To establish and conduct a farm for boys on a plan sufficiently extensive to afford instructions.

- To restore handicapped and homeless boys in need of care and protection to a normal life wherever possible through a carefully planned and executed manner, involving relief, employment, medical care and education.

- To establish and conduct a place for the social betterment of young boys.

- To establish, maintain and provide a place for young boys so as to give them an opportunity to grow and develop in “social usefulness.”

The village was designed to operate differently from the more traditional homes for boys. An early Boys Village publication described the experience:

The one inflexible rule of Boys’ Village [as it was originally punctuated]is that its boys shall not be regimented. The atmosphere is personalized and homelike, and the boys are guided rather than compelled by a trained staff. The boys live normally and wholesomely, with personal interests, possessions and friends, and they attend the churches of their choice and the Milford public schools where many of them are at the head of their classes. A sense of responsibility and self-sufficiency is developed in them to a far greater extent than is possible in “institutionalized” homes.

Slavin’s strategies to reach young people early—beginning with his radio show and First Offender Club—were visionary. His next project was to write a screenplay for a film called First Offenders, produced in 1939, with the tagline, “Stop turning kids without a chance into men without hope!” The plot involved a high-school boy convicted of killing his girlfriend and the crusading young assistant district attorney who attempts to save him by establishing a farm for first offenders. The movie, released nationally by Columbia Pictures, was directed by Frank McDonald and starred Walter Abel and Beverly Roberts. Roberts co-starred with a young Humphrey Bogart in 1936’s Two Against the World. McDonald was best known for directing Gene Autry and Roy Rogers westerns and directed more than 100 movies, according to IMDb.com. An Internet search reveals a French movie poster advertisingFirst Offenders. It received favorable reviews, one stating that it “deals intelligently and forcefully with the ever growing problem of delinquent youth” (The Hartford Courant, March 25, 1939).

Slavin published several comic books in 1945 under the banner Courage Comics and the auspices of Boys Village. The theme of the stories was courage in the face of adversity; the comics featured scenarios relating to crime, athletics, and heroism in World War II. Characters included U.S. Navy Lieutenant Chick Courage, boxer K.O. Brown, and a dog named Red Badge. One recurring character closely resembled Slavin. “Sheriff Jack” would save young offenders from a jail sentence, preventing them from being exposed to hardened criminals. He dissuaded them from pursuing a life of crime by taking them under his wing and having them join the First Offender Club.

In 1947 Slavin resigned his post as president of Boys Village and Daniel J. Adley was named to fill the position. Adley and his four brothers and sisters had been orphaned after their father was killed in a railway accident and their mother died a few months later. The children were placed in an orphanage, and Daniel was later moved to Connecticut Junior Republic in Litchfield. In spite of their difficulties as children, in 1926 Daniel and his brothers founded Adley Express, one of the largest trucking companies in the Northeast. Adley not only had the financial savvy he brought to his position as board president but also first-hand experience in group-home environments. He had a very personal and emotional motivation to see Slavin’s vision fulfilled.

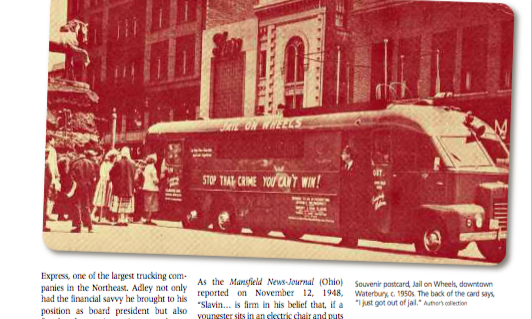

Slavin also stepped down as high sheriff. This gave him time to implement another plan to help support Boys Village: a traveling crime-education center he called “Jail on Wheels.” He outfitted a bus with exhibits displaying modern equipment and methods used by police for outwitting and punishing criminals, including the science of fingerprints, recording devices, forensics techniques, a lie detector, and means of restraining and punishing criminals. The Jail on Wheels included a reproduction jail cell and an electric chair identical to the one used at the state prison in Wethersfield. Slavin’s intent was to discourage young people from pursuing a life of crime by showing them the possible consequences of their wrongs. As the Mansfield News-Journal (Ohio) reported on November 12, 1948, “Slavin … is firm in his belief that, if a youngster sits in an electric chair and puts the leg irons around his calves and the steel cap on his head, he will never forget what the reward is for high achievement in the world of crime.”

Slavin also stepped down as high sheriff. This gave him time to implement another plan to help support Boys Village: a traveling crime-education center he called “Jail on Wheels.” He outfitted a bus with exhibits displaying modern equipment and methods used by police for outwitting and punishing criminals, including the science of fingerprints, recording devices, forensics techniques, a lie detector, and means of restraining and punishing criminals. The Jail on Wheels included a reproduction jail cell and an electric chair identical to the one used at the state prison in Wethersfield. Slavin’s intent was to discourage young people from pursuing a life of crime by showing them the possible consequences of their wrongs. As the Mansfield News-Journal (Ohio) reported on November 12, 1948, “Slavin … is firm in his belief that, if a youngster sits in an electric chair and puts the leg irons around his calves and the steel cap on his head, he will never forget what the reward is for high achievement in the world of crime.”

Slavin relied on donations from visitors to cover expenses. After one year of traveling the country, the mobile jail had been toured by more than a million people. Slavin paid off the remaining debts for Boys Village and put a second Jail on Wheels out on the road. Immediately thereafter, plans for a badly needed expansion of Boys Village were undertaken. Human services agencies from around Connecticut had made requests on behalf of another 150 boys.

Slavin died in 1972 at the age of 76. His obituary in the Connecticut Sunday Herald (November 5, 1972) said, “Sheriff Slavin was a tough-jawed, grass roots politician, who fought hard for the one thing he believed in most, keeping the kids out of trouble. A man like this, especially in the promiscuous young society of today, will be sorely missed.”

Boys Village is still serving Connecticut with sophisticated behavioral-health programs focusing on young people and their families. It has been re-named Boys & Girls Village and is still at its original site on Wheelers Farms Road. Its services and reach have grown with the addition of a second campus, in Bridgeport. The facility serves more than 700 clients a year, although relatively few live on the campus. Daniel Adley’s family has been directly involved in its operation for the past 75 years.

Perhaps the organization’s mission can best be summed up with its founder’s own words: “I believe in giving an American kid a chance to grow right.”

Michael Dooling is the archivist at the Mattatuck Museum. He wrote “Three Generations in the Newspaper Business” (Fall 2010) and “Connecticut’s Sleepy Hollow” (Fall 2012).

Click here to subscribe or purchase the current or back issue!