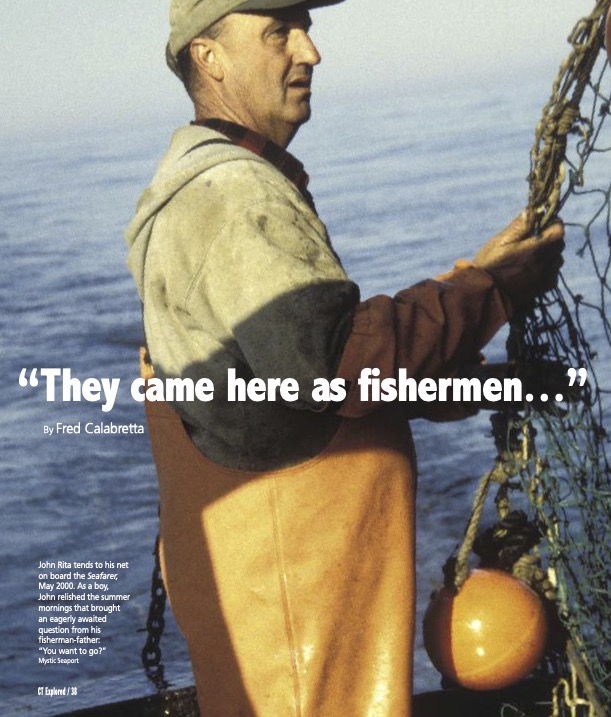

John Rita tends to his net on board the Seafarer, May 2000. As a boy, John relished the summer mornings that brought an eagerly awaited question from his fisherman-father: “You want to go?” Mystic Seaport Museum

by Fred Calabretta

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Only a couple of blocks from the tidy streets and stately homes are the sounds, sights, and yes—occasional odors—of a working waterfront. This is Stonington Borough, for many decades a fishing village and to a considerable extent a Portuguese fishing community on the border of Connecticut and Rhode Island. Changes have come to Stonington in recent decades, yet somehow it remains, at least in part, a fishing village. And the Portuguese presence, though diminished, has survived.

In 1993 Mystic Seaport Museum began a three-year project called the Stonington Fishing Oral History Project to document the history and current status of the Stonington Fleet. It generated 1,600 photographs and 35 oral history interviews. In addition to a number of fishermen, those interviewed included family members and others associated with the fishing fleet. The strong Portuguese presence in the Stonington fleet emerged as a central theme and the story of the fleet was in large part a story of immigration.

Located on a peninsula of land in southeastern Connecticut, Stonington Borough is part of the town of Stonington. Beginning in the 1750s, the original Yankee residents of the Borough—also known as Stonington Village—looked to the ocean as a place to make a living. They had brought Great Britain’s island-nation traditions with them. Fishing, ship and boat building, and later whaling, sealing, and steamboats all provided work opportunities and enriched the town’s economic and cultural makeup. Of these pursuits, only fishing survives, characterized by a local history spanning more than 250 years.

A major change to the cultural fabric of the village began in the 1850s when two families of Portuguese descent settled in Stonington. Substantial numbers of immigrants from many parts of the world, including not just Portugal but also Italy, China, Canada, and Vietnam, have been naturally drawn to coastal towns in the United States. The fundamental explanation for this may be summarized in one word: fishing. Commercial and subsistence fishing rank high in traditional importance in many cultures worldwide. Such New England ports as Gloucester, New Bedford, Provincetown, and Point Judith have also attracted Portuguese fishermen and their families.

The first Portuguese immigrants in Stonington were from the Azores, an island chain that is part of Portugal but is located about 900 miles west of the mainland in the mid-Atlantic Ocean. They were not the first Portuguese-speaking people in southeastern Connecticut. Other Azoreans—and Cape Verdeans—had previously arrived in New London County as sailors on whaleships. The people of the Azores share the language and traditions of Portugal. Once established in Stonington, they provided a base of support for additional relatives and friends to come from the old country. Their motivation for coming reflected the essence of the immigrant experience: They viewed the United States as a land of opportunity. The Portuguese presence in Stonington increased steadily for 100 years.

As Portuguese families found a home in town, many of them also found an occupation they knew well. Taking their place alongside the town’s other fishermen, they turned to the resources of the sea. Often they joined the crew of a friend or relative’s boat and were content to do so, although many eventually acquired boats of their own.

These Stonington newcomers joined local fishermen of various ethnic backgrounds. Traditionally, they all have depended on bottom-dwelling species known as groundfish including flounder, scup, and a popular non-finfish, the lobster. Cod and haddock long ranked high in importance, but their populations have diminished dramatically due to decades of intense fishing.

Beginning in the 19th century, much of the Stonington catch was sold in New York. Most contemporary Portuguese fishermen seem well aware of local fishing history, including their cultural roots. These excerpts from 20th-century oral histories paint a picture of their experience.

We had people from the Azores, the Madeiras, and then the mainland. It was a mixture of people from different parts of Portugal.

There were a lot of families. Families would come here and spread the news that there was a good living to be made here, and the rest of the family would come over here. A lot of them. Like you take the Maderia family. That’s a great big family. The Roderick Family. They were some of the biggest families in town, as far as the Portuguese people go. And there were others, even though the names are not the same, you know, sisters married other people. It was a very close community, the Portuguese community.

Joe Rendeiro, fisherman, 1994

In 1907 Manuel and Rose Roderick moved to Stonington from the Azores, establishing what would become a virtual fishing dynasty. Among their 14 children were 8 sons, all of whom followed their father into fishing. The family’s fishing experiences spanned multiple generations.

My mother’s side of the family, all her brothers were fishermen and my grandfather was a fisherman and a lobsterman, and my great uncles on my mother’s side are all fishermen. Her mother was a Roderick. I guess it was thirteen brothers and sisters, and all the brothers were draggermen.

Michael Grimshaw, lobsterman, 1995

I was born in Murtosa, Portugal, in 1934. It’s a little fishing community. I came here as a very young baby. My father… after a few years of working in the factories, he didn’t like it. And he was invited by a friend of his, Alfred Rubello, who was a fisherman from a town just south of us. They knew each other, and he invited him to come down here and fish.

Of course, back then Portuguese fishermen were in demand because they were taught the basics that most people have to learn after they go fishing. These people were taught this as young men. … You came home from school, if there was a school, and you helped your parents to survive. So, these people knew their business, their jobs, long before they came here. They came here as fishermen, which was considered an art in the old country. It was something that you didn’t learn in school, but it took a talent to know it. You had to have knowledge, and this knowledge was already in these people.

Joe Rendeiro, 1994

By 1950 more than half of Stonington’s several hundred fishermen were Portuguese, and their native language was commonly heard spoken in the streets. For these people, fishing is a way of life, rich in cultural, community, and family tradition.

By 1950 more than half of Stonington’s several hundred fishermen were Portuguese, and their native language was commonly heard spoken in the streets. For these people, fishing is a way of life, rich in cultural, community, and family tradition.

The fishermen I’ve known over the years, and I’ve heard the stories about my great uncles and all that, and they were all Portuguese. And I’ve found that the boats can change, and the fishing conditions can change, but the people really don’t. I think if you took my Uncle Danny today, and put him on a boat, he’d be the exact same type of fishermen as he was when my father started fishing with him in the ’40s.

And I think that has a lot to do with the closeness of Portuguese families.

It’s getting away from that now, because now we’re second and third generation Americans, but it used to be that Sunday was the day that you went to the oldest grandmother’s house. And you went there and had a nice big Portuguese dinner, and the whole family came. And I think that’s what’s kept the feeling of community with the fisherman going over the years. They all come from the same backgrounds, and they all had relatives that were fishermen. And fishing was a great business to get into. There was, there still is a lot of support within the Portuguese community for fishermen, and for the life they choose.

Michael Medeiros, son of a fisherman, 1994

Despite the challenges associated with the career, most fishermen of the past seem to have enjoyed their work. They loved being outdoors rather than “cooped up” in factories or other indoor places of work. They enjoyed the freedom and feeling of independence, expressed by one fisherman as feeling “free as a bird.”

But while fishing brings satisfaction to most fishermen, it also imposes hardship on their families. Activities as fundamental as shared meals are affected by a fisherman’s schedule. Wives and children also worry; they are well aware of the hazards of the business. They know that accidents, injuries, and even death are far too common. Fishermen work in one of the most dangerous occupations in the United States. According to U.S. Department of Labor statistics relating to occupational deaths, in 2011 the fishing industry’s rate of fatal injuries ranked number one among all occupations, at just over 127 per 100,000. And there are other concerns. Mothers and wives must manage homes, children, and financial affairs during the long hours the husband and father is fishing or maintaining, repairing, or simply checking on his boat. All family members experience the burden of an income that is unpredictable and inconsistent.

The hours, there’s a lot of hours. How does it affect the family? Well it does. You are not with your family a lot. There are a lot of things you can’t do, that you like to do with the children. Holiday’s don’t correspond with theirs. When they get a day off, we don’t take days off. We fish holidays, weekends, and weather.

Tim Medeiros, fisherman, 1994

As Portuguese immigrants infused the ranks of the fishing fleet and the population of Stonington Village, several institutions and events became very important, both to the Portuguese and to the community as a whole. St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, located in the village and established in 1851, became very important, both to the Portuguese and to the community as a whole. St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, located in the village and established in 1851, became the center of Portuguese spiritual life. The Holy Ghost Society, a social and religious organization, was established in the village in 1914. Common in Portuguese communities worldwide, it remains active today, based in a building on Main Street.

The Stonington fishing fleet has gained its greatest visibility during the annual Blessing of the Fleet. This event, founded in 1954, was based on similar events in other Portuguese fishing communities. For more than 50 years it fused two themes of great importance to the fishermen and their families: It was a celebration of the fishing way of life and a memorial to fishermen who had lost their lives pursuing a dangerous occupation.

A large dockside celebration on Saturday night offered music, dancing, and Portuguese foods. Sunday began with a memorial fishermen’s mass, followed by a street parade, a dockside memorial tribute, the actual blessing of the boats by the region’s Catholic bishop, and finally a procession of boats to a rendezvous outside the harbor, where a memorial wreath was placed in the sea.

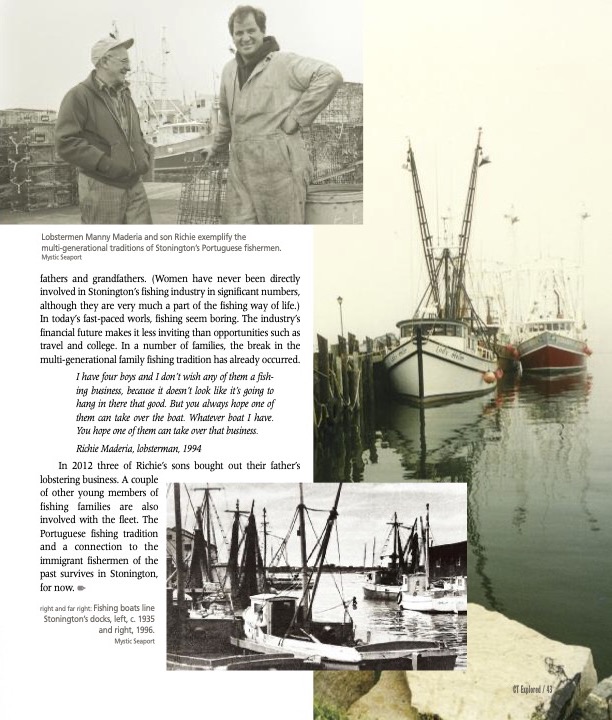

top left: Lobstermen Manny Maderia and son Richie exemplify the multi-generational traditions of Stonington’s Portuguese fishermen. Mystic Seaport Museum; right and bottom: Fishing boats line Stonington’s docks, left, c. 1935 and right, 1996. Mystic Seaport Museum

The event, most of whose organizers have been members of Portuguese fishing families, drew heavily from similar celebrations in the old country. The parade included a rolling statue of St. Peter, patron saint of the fishermen, towed by fishermen and their sons. A Portuguese music and dance group was always a highlight of the parade, adding another strong cultural accent to the event.

In recent years the Blessing of the Fleet has become smaller. The Saturday night celebration and Sunday morning’s parade are no longer held. Although these activities attracted thousands of participants, rising expenses sealed their fate as costs such as insurance and the required police presence continued to rise.

Still, the Blessing survives as members of Portuguese fishing families work to continue the elements they consider most important—the special Mass at St. Mary’s Church, a memorial service at the dock, the blessing of the boats, and the laying of memorial wreath in the waters of off Stonington Harbor.

A stone monument located near the end of the town dock remains a focal point for the event. It bears the names of 38 local men who have lost their lives fishing. A number of the names etched into the monument, such as Roderick, DeBragga, Pont, and Maderia, reflect the losses within the Portuguese community.

Ann Rita has helped organize the Blessing for many years. She knows the fishing life very well. Her husband recently retired from the occupation, her father was a fisherman and lobsterman, her brother and his sons are lobstermen, and her sister is married to a fisherman. Ann recently summarized the meaning of the Blessing to her and her family. “The Blessing will never die. We’ll always honor our fishermen.”

Not surprisingly, the boats of the fishermen of Stonington are vital to their work and central to their identity. Often named after wives or daughters, they function as a large and complex tool of their trade. For many decades the fishermen of Connecticut relied on small sailboats called smacks, which were an adequate platform for the principal fishing methods of the day: hand lining and the use of seine nets and fish traps. Hand lining involved hundreds of hooks attached to long lines. Seine nets were long nets drawn in a large circle to entrap fish. Complex floating fish traps employed nets, floats, and anchors.

Shortly after 1900, the development of internal combustion engines revolutionized the fishing industry. Trawling—dragging a large net across the ocean floor—became the fishing method of choice. Diesel engines extended the power and range of Stonington’s fishing fleet several decades later. By the 1970s boats had become much larger and more powerful than the tiny smacks. Efficiency was also greatly increased, putting increased pressure on fish stocks. Today the boats of the fleet range from lobster boats as small as 25 feet long to offshore “trip” boats and scallop boats up to 100 feet long.

Throughout the 20th century the fleet experienced cycles of boom years and lean times. By January 1950 there were 37 draggers fishing out of Stonington. Today there is fewer than half that number. Natural cycles and overfishing have accounted for the ups and downs.

Commercial fishing has become a complicated business—despite the growth in diners’ demand for fish. Vast quantities of fish and other seafood are imported. Diminished stocks of lobster and many species of fish are a reality. Several decades of increased government regulation—intended to protect depleted fish stocks—have greatly frustrated Stonington’s fishermen and driven some away from the work they once enjoyed. Catch limits, designated numbers of fishing days, and other restrictions have inhibited their ability to determine their own earning potential. Still, there are some bright spots, such as an ongoing successful harvest of scallops.

Staying abreast of government regulations has become what seems to the fishermen to be an ever-increasing burden, made more complicated by the geographic location of the Stonington fleet. Depending on the specific fishing grounds of choice for individual fishermen or lobstermen, Stonington’s proximity to New York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and federal waters has forced some members of the fleet to stay current on four sets of complex laws and regulations.

Throughout the 20th century, and especially in the years following World War II, major changes have come to Stonington, as with most coastal communities as our relationship with the oceans changed. Once primarily a place of work, today the sea is primarily a playground. The village of Stonington now holds a strong allure for those seeking recreation, relaxation, and inspiration. Coastal property is much in demand. Resulting high real estate values have placed Stonington homes beyond the reach of most working-class families, who have moved to outlying areas. One long-time Stonington fisherman and borough resident summarized the change:

That’s all it was, mainly a fishing town. There just aren’t any [fishermen]around anymore. I don’t know of anybody in town here that used to be a fisherman, my age or anything. There’s no fishermen around here. I’m the only one.Manny Maderia, fisherman and lobsterman, 1993

Change has also come to the Portuguese fishing families of Stonington. Most significantly, a majority of boys and young men are no longer drawn to the work that so appealed to their fathers and grandfathers. (Women have never been directly involved in Stonington’s fishing industry in significant numbers, although they are very much a part of the fishing way of life.) In today’s fast-paced world, fishing seems boring. The industry’s financial future makes it less inviting. than opportunities such as travel and college. In a number of families, the break in the multi-generational family fishing tradition has already occurred.

I have four boys and I don’t wish any of them a fishing business, because it doesn’t look like it’s going to hang in there that good. But you always hope one of them can take over the boat. Whatever boat I have. You hope one of them can take over that business.

Richie Maderia, lobsterman, 1994

In 2012 three of Richie’s sons bought out their father’s lobstering business. A couple of other young members of fishing families are also involved with the fleet. The Portuguese fishing tradition and a connection to the immigrant fishermen of the past survives in Stonington, for now.

Fred Calabretta is curator of collections and oral historian at Mystic Seaport Museum. He managed the museum’s Stonington Fishing Oral History Project and edited Fishing Out of Stonington (Mystic Seaport, 2004).

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s maritime history on our TOPICS page

Read more stories about Connecticut’s history of immigration in the Fall 2013 issue.