By Gregg Mangan

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Summer 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

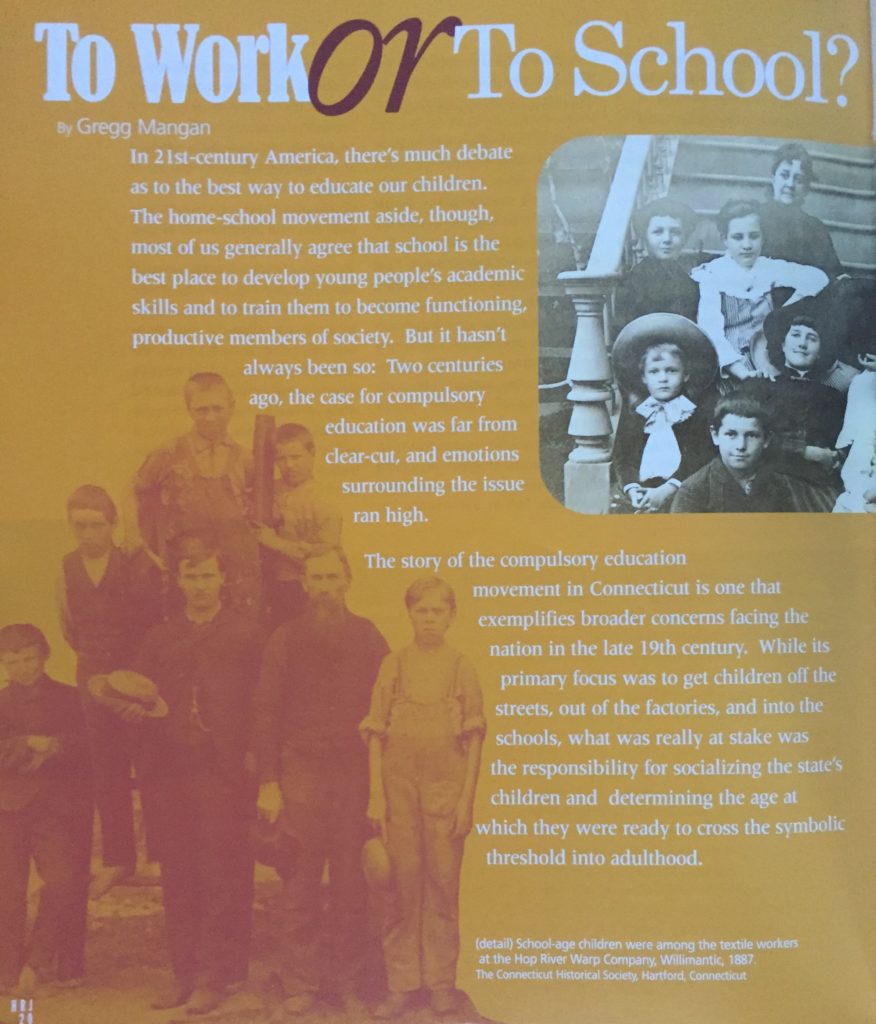

In 21st-century America, there’s much debate as to the best way to educate our children. The home-school movement aside, though, most of us generally agree that school is the best place to develop young people’s academic skills and to train them to become functioning, productive members of society. But it hasn’t always been so: Two centuries ago, the case for compulsory education was far from clear-cut, and emotions surrounding the issue ran high.

The story of the compulsory education movement in Connecticut is one that exemplifies broader concerns facing the nation in the late 19th century. While its primary focus was to get children off the streets, out of the factories, and into the schools, what was really at stake was the responsibility for socializing the state’s children and determining the age at which they were ready to cross the symbolic threshold into adulthood. The movement emerged from primarily middle-class concerns about the best way to prepare children for the future. Its proponents saw themselves as champions of children’s rights. In their view, mandatory schooling provided a brighter future for the state’s children and ensured safety and stability for the nation by supplying a well-trained workforce and educated electorate.

Opponents of compulsory education, many of whom either needed or wanted their children to be brought up as members of a professional workforce, railed at the idea of the government’s dictating to them how their children should be raised. The debate that played out in the state’s newspapers and political forums called into question the government’s power to infringe on parents’ rights. It fostered class conflict and redefined social and cultural relationships. Persistent public pressure and arduous legislative debate during the second half of the 19th century drove the state to forever change the role of children in families and society—and to alter the very notion of what it meant to be a child.

The first Connecticut schools were established in the early 17th century and were soon followed by the colony’s first education-related legislation. The 1650 Connecticut “Act for Educating Children” was derived from a law passed a few years earlier in Massachusetts. The act was Connecticut’s first step toward socialization through education, directing parents to ensure their children could read and comprehend the laws they were expected to live by. Subsequent legislation passed by the state during the next two centuries established a variety of loosely enforced age restrictions and financial penalties to be paid by parents for poor attendance. These laws were generally well received and supported by the public—until waves of immigrants began landing on American shores.

Immigrants of the late 19th century, arriving primarily from southern and eastern Europe, brought with them ideas about education and family obligations that differed from those established by New England’s puritan founders. While the views of working-class immigrants were grossly underrepresented in the local media, historian Stephen Lassonde noted in his book Learning to Forget: Schooling and Family Life in New Haven’s Working Class, 1870-1940 (Yale University Press, 2005) that many new arrivals to this country felt schooling prolonged a child’s dependence on his or her parents and that while at school children missed opportunities to learn a trade or earn much-needed income for their families. Working-class families who found their financial security threatened by the death, illness, or disability of an adult family member often depended on the extra money their children provided. To them, children’s moving in and out of the workforce while balancing family responsibilities was good preparation for the challenges they would face as adults.

In addition, Lassonde notes, immigrants coming from cultures rich in the oral traditions of their elders saw little use for textbooks; they felt children learned more from direct life experience. Furthermore, formal education threatened their cultural identity by imposing new, “American” values on their children, upsetting long-held familial practices and relationships.

Advocates of compulsory education saw immigrant families as exploiting their children for labor. Vitriolic editorials in the Hartford Courant, including one in the July 4, 1872 edition, maintained that the decision to educate children must be taken away from parents for several reasons: Many parents were cited as being “vicious and cruel and indifferent to the child’s welfare.” Others asserted that drunkenness or “some evil home influence” was to blame for truancy and that education provided the only path to sobriety, morality, and independence. Education was touted as “the great equalizer,” the only institution that could empower the lower classes to assimilate and rise in society.

The state legislature continued to respond to public pressure from educational proponents by enacting new education laws throughout the mid- and late 19th century. An 1842 act decreed that no child under the age of 15 be employed in manufacturing without evidence of some type of formal schooling. Unfortunately for reformers, many prospective employers ignored the requirement that a child present a certificate signed by his or her teacher upon application. In 1869 the law was updated, increasing the mandated school attendance period to three months for children under age 14 and creating a board of officials to inspect local businesses thought to be illegally employing children. An 1871 revision made schooling mandatory even for children of the unemployed, who were previously allowed exemptions due to financial hardship. Those found in violation of these laws paid a penalty of $5 per week for a maximum of 13 weeks. Still, many ignored education laws, and factories found ways of employing children “off the books” by hiring adults or contractors who then “subcontracted” their work out to the children. These jobs often fell to younger boys and girls, who worked for less pay than their older counterparts.

In an effort to increase compliance, advocates of mandatory education tried to convince their opponents that children rarely labored out of actual necessity and that few were employed with the best interest of the child in mind. An educated worker, reformers asserted, was better equipped to provide both a steady wage for his family and skilled labor for the country. An 1883 Hartford Courant editorial agreed: “If those who are just now deploring the scarcity of skilled artisans and mechanics…will make a little inquiry they will learn that of two carpenters the one who can find the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle . . . and can compute the amount of lumber needed in the construction of a building, will always command better wages.”

In an effort to increase compliance, advocates of mandatory education tried to convince their opponents that children rarely labored out of actual necessity and that few were employed with the best interest of the child in mind. An educated worker, reformers asserted, was better equipped to provide both a steady wage for his family and skilled labor for the country. An 1883 Hartford Courant editorial agreed: “If those who are just now deploring the scarcity of skilled artisans and mechanics…will make a little inquiry they will learn that of two carpenters the one who can find the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle . . . and can compute the amount of lumber needed in the construction of a building, will always command better wages.”

The reformist platform strongly embraced the concept of children’s rights. Insisting that children had the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as provided in the Constitution, education advocates argued that it was despicable to force children to forego those rights just so they could help produce cheap consumer goods. Without an education, reformers urged, children born into poverty did not have the tools necessary to work themselves out of it. The movement also recognized that education must begin early, as scientific evidence had begun to illuminate children’s physiological growth and the importance of early brain development.

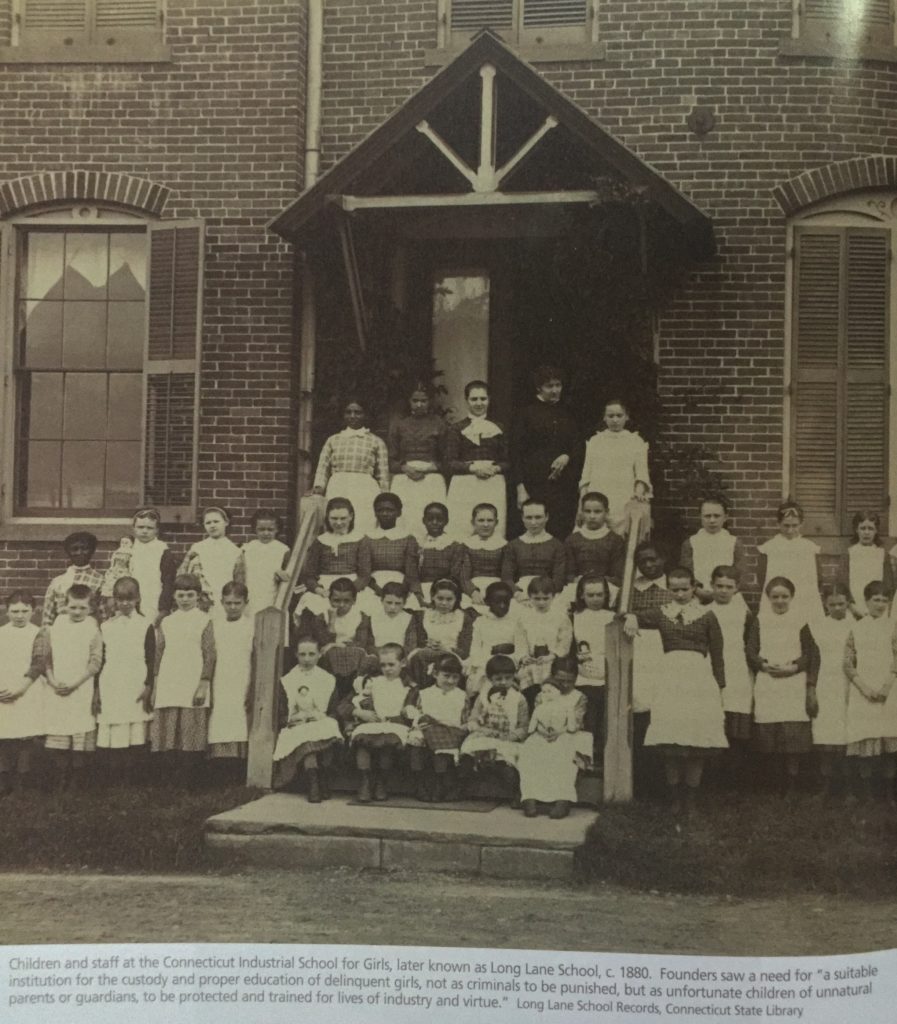

Though many advocates of compulsory education had children’s best interests at heart, others simply felt that socialization through education provided greater prospects for maintaining an orderly society. Unemployed children with too much free time on their hands often found ways of getting into trouble. In this respect, compulsory education was framed as a way of protecting children from the “dangerous classes” and transforming them into good citizens. During several economic downturns in the late 19th century, high rates of unemployment and low school attendance among children meant finding new ways to keep them off the streets. “Crime is directly the child of ignorance and idleness,” the Hartford Courant reported. Increases in juvenile crime led to crowding at state reform schools, which existed primarily because other types of schools did not. An 1871 study found that three-quarters of the boys in state reform schools had never before had any formal school instruction. Compulsory education became a means to put an end to ignorance and vagrancy and make the streets a safer place for law-abiding citizens.

Another factor in the movement’s growing momentum was the pride New Englanders felt at having always considered themselves national leaders. During an address to the state legislature on March 10, 1871, the Reverend Samuel Rockwell assured doubters that maintaining Connecticut’s reputation meant producing citizens of “superior intelligence.” At the time of Rockwell’s address, Connecticut’s school year lasted eight months and eight and a half days, the longest of any state in the nation. In a commencement address the following year, Governor Marshall Jewell proclaimed Connecticut to be at the forefront of education. “In the future,” he claimed, “when we have crystallized and Christianized the whole continent, we have every reason to expect that they [Connecticut students] will be found in the front rank, where they have always been, fighting for liberty and for law.”

Although the compulsory education movement had a strong middle-class following, it was never able to develop an entirely unified front. Many advocates drew sharp class distinctions in their arguments and did not think that intermingling the classes served their best interests. Some feared the influence ignorant children might bring into the classroom. Others worried that an entire population of educated people left no one to employ in society’s more menial jobs.

As remains the case today, determining who should pay educational costs was paramount and spurred heated debate. The fiscal controversy started with a state law passed in 1868. With less than half of school-age children in Connecticut receiving any formal education at the time, the state passed the Free School Law, eliminating tuition at public schools and transferring the fiscal burden to taxpayers. The law made each town responsible for raising enough money to operate its schools for a minimum of six months per year.

In addition to the tax burden, the state also encouraged responsible citizens to seek out truant children, counsel them, and in the cases of the truly impoverished, provide them with money and clothing. This last suggestion in particular struck a nerve with the public, setting the stage for a debate about just where the average citizen’s responsibilities ended.

In 1885 a bill passed compelling children to “regularly” attend school from ages 9 through 16. This law excluded, however, children considered destitute of suitable clothing. Detractors of the law condemned the very notion of suitable clothing as prerequisite for school attendance and scorned the implication, however remote, that private citizens were now somehow obligated to ensure schoolchildren were adequately clothed. The concern was that once children became excluded due to a lack of suitable clothing that it would only be a matter of time before it was brought before the taxpayers to provide those clothes.

The author of an angry editorial reprinted in the Hartford Courant, disgusted at taxpayers’ being charged with providing free books to schoolchildren, drew the line at supplying free clothes (which the new law did not explicitly charge the public with supplying). The author wondered, probably rhetorically, if the next exclusion would require taxpayers to provide free meals to malnourished children or if children might be denied education because they lived in homes without adequate sanitary facilities. “Of course, it was bound to come. Compulsory education officers have found children who cannot go to school because their clothing is unfit. This, by analogy, is to furnish the school board with an argument for adding free clothing to free school books.

“By analogy,” the editorial continued, “every child attending the schools should be thrust into a bathtub on arrival, washed by the teachers, combed by the janitors, and rubbed down by special corps of barbers, shampooers, manicures and pedicures, while tailors measure him and dress makers her for nice new clothes and cooks attend to the table orders.” The attack concluded with a simple warning: “The public must furnish school sites, buildings, heat, light, and instruction and the parents should do the rest . . . Further than this the state cannot go without entering the area of socialism, with its logical and actual tendency to anarchy.”

These fears may sound alarmist to us today, but taxpayers’ complaints at that time reflected the broader, deeper concerns spurred by the immigration movement. Although these waves of new settlers may not have brought with them designs on overthrowing the American economic system, that did not stop the compulsory education debate from taking on an urgency inextricably linked to issues of national security. In governments abroad where only the ruling classes had a say in policy, the intelligence of the lower classes seemed to matter little; but America was a democracy. “If you put a ballot in a man’s hand, you must put knowledge in his brain,” the Hartford Courant advised. “The safety of the government . . . lies in a public school system that shall reach with equal privilege and equal obligation and opportunity of education every child in the land.”

Beyond the need to ensure safety by providing a more controlled and uniform approach to socialization through education, came a desire to justify our faith in democracy to the world. Monarchs always claimed that republican government did not work because the masses were unfit to rule. Advocates of the compulsory education system felt a responsibility to prove these elitists wrong. At an address delivered at the annual Connecticut Teacher’s Association meeting in October 1873, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, discussing traditional aristocratic approaches to education, claimed, “They had the idea that the top could take care of the bottom; we believe that by taking care of the lowest the rest can take care of themselves . . . Our notion is democratic, we are attempting to educate the people, not a class.”

Beyond the need to ensure safety by providing a more controlled and uniform approach to socialization through education, came a desire to justify our faith in democracy to the world. Monarchs always claimed that republican government did not work because the masses were unfit to rule. Advocates of the compulsory education system felt a responsibility to prove these elitists wrong. At an address delivered at the annual Connecticut Teacher’s Association meeting in October 1873, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, discussing traditional aristocratic approaches to education, claimed, “They had the idea that the top could take care of the bottom; we believe that by taking care of the lowest the rest can take care of themselves . . . Our notion is democratic, we are attempting to educate the people, not a class.”

With so much perceived to be riding on the outcome, it is no wonder that it took external events to slowly defuse the compulsory education debate. Advances in industrial mechanization at the beginning of the 20th century decreased the demand for child labor, and a tightening of enforcement loopholes made regular school attendance standard for Connecticut’s children. But despite the achievements of 19th-century education advocates, it would be premature to consider the issue resolved. The story of compulsory education is one without a clearly defined beginning and end. It is true that a great deal of the publicity and legal wrangling surrounding the issue tapered off by the early 20th century, but the evolution of societal priorities ensures that the emphasis on education will continually be redefined by changes in politics, economics, and cultural values. While the compulsory education movement brought large numbers of children into the classroom by the end of the 1800s, it was not until the 1930s that children were required to attend high school and only in 1998 that the state lowered the compulsory school age from seven to five. Perpetually evolving classroom curricula and initiatives such as the federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 demonstrate the degree to which we are still struggling to devise effective strategies and a sound, educational infrastructure in our pursuit of the best way to prepare our children for adulthood.

Gregg Mangan is manager of digital humanities at Connecticut Humanities.

Read More!

Go to our Topics page about Childhood in Connecticut history