By Ross K. Harper

(c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2012

Subscribe to Receive Every Issue!

All images courtesy of Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc.

Archaeology is unique among the sciences in that it uses discarded bits and pieces left behind by past cultures to reconstruct human history. Archaeological excavations at a number of 18th-century house sites in Connecticut have revealed that colonial families had remarkably diverse household economies and that the frugality that is considered one of New England’s steadiest habits was an early part of Yankee culture and identity.

The household economy of Connecticut Yankees was key to their success. It helped them prosper and get through times of war, family tragedy, and economic inflation, and it served them well when they migrated out to the frontiers in great numbers. In the opening lines of her influential book The Frugal Housewife, published in 1829, Lydia Child advised:

The true economy of housekeeping is simply the art of gathering up all the fragments, so that nothing be lost. I mean fragments of time, as well as materials. Nothing should be thrown away so long as it is possible to make any use of it, however trifling that use may be; and whatever be the size of a family, every member should be employed either in earning or saving money.

People today are often surprised to learn that in the colonial period it was common practice for families to toss their household trash right out their doors and windows into the yard. And people simply lost things as they went about their daily business: a shoe buckle, a child’s clay marble. Over time these artifacts accumulated in layers and became buried. Archaeologists call household refuse deposits middens, and each one is a unique artifact archive containing important information about the people who used these objects.

The contents of middens not only tell us what people were doing in their houses and yards, they can also indicate when these activities took place. Objects are dated by how the technologies and styles of artifacts evolved over time. For example, most ceramic tablewares used in colonial Connecticut were made in England and are dated by changes in patterns and manufacturing techniques. Clay tobacco pipes, also mostly made in England, are dated by the shape of their bowl, their maker’s mark, and the diameter of the hole in their stems. (Essentially, as tobacco became cheaper, the bowls became larger and the stems became longer to allow the smoke to cool.) Though hard currency often became scarce during the colonial period, occasionally an archaeologist might find a well-worn copper halfpenny with the mint date neatly stamped on it.

Along with midden deposits, archaeologists also search around old houses for a simple fence post hole, a stone-lined well, a privy (outhouse) vault, or even a cellar hole from a house that once stood on the property. Such “features,” as they’re called, also typically contain artifacts that can be used to indicate how and when they were used—and sometimes even by whom.

Archaeological excavations take place outside of standing old houses, in farmer’s fields, or even right next to the curb of a busy interstate that was once a colonial road. For artifacts and features to fully yield their information potential they must be excavated in a controlled and systematic way. When properly excavated, individual artifacts and features can often be correlated with historical documents and associated with a particular family during a specific time. This photo essay features a few of the hundreds of thousands of artifacts found at the Sprague, Goodsell, and Daniels house sites.

The Sprague house offers a particularly vivid illustration of the way people lived in early 18th-century Connecticut. In the first decade of the 1700s, Ephraim Sprague, then a young man, married a local woman named Deborah Woodworth, and they built a house on a fertile terrace in the Hop River Valley in Lebanon (now in Andover). As was typical on the frontier, the family was rich in land and timber, but materially poor. Whatever tools, dishes, and clothing they didn’t carry in had to be made, repaired, purchased from as far away as Hartford or Norwich, or done without. The Spragues had eight children, and Ephraim served Lebanon as selectman, captain in the local militia, deacon in the local church, and representative to the colonial legislature. Although the colonial records relate information about Ephraim’s property and positions in society, they reveal few details about how the Spragues actually lived their day-to-day lives.

Archaeologists discovered the remains of Ephraim Sprague’s house buried and hidden in a cornfield. A cellar hole containing burned artifacts and carbonized wood indicated the house had burned down in a catastrophic fire in the 1750s. With two cellars and two fireplaces, the house was remarkably long and narrow, measuring about 72 feet by 16 feet. The architectural plan was taken directly from the cross-passage houses of the West Country of England, a form that no longer exists in America. Artifacts from the house area and an adjacent refuse midden provided unprecedented insights into the household economy of an early Connecticut family.

Archaeologists discovered the remains of Ephraim Sprague’s house buried and hidden in a cornfield. A cellar hole containing burned artifacts and carbonized wood indicated the house had burned down in a catastrophic fire in the 1750s. With two cellars and two fireplaces, the house was remarkably long and narrow, measuring about 72 feet by 16 feet. The architectural plan was taken directly from the cross-passage houses of the West Country of England, a form that no longer exists in America. Artifacts from the house area and an adjacent refuse midden provided unprecedented insights into the household economy of an early Connecticut family.

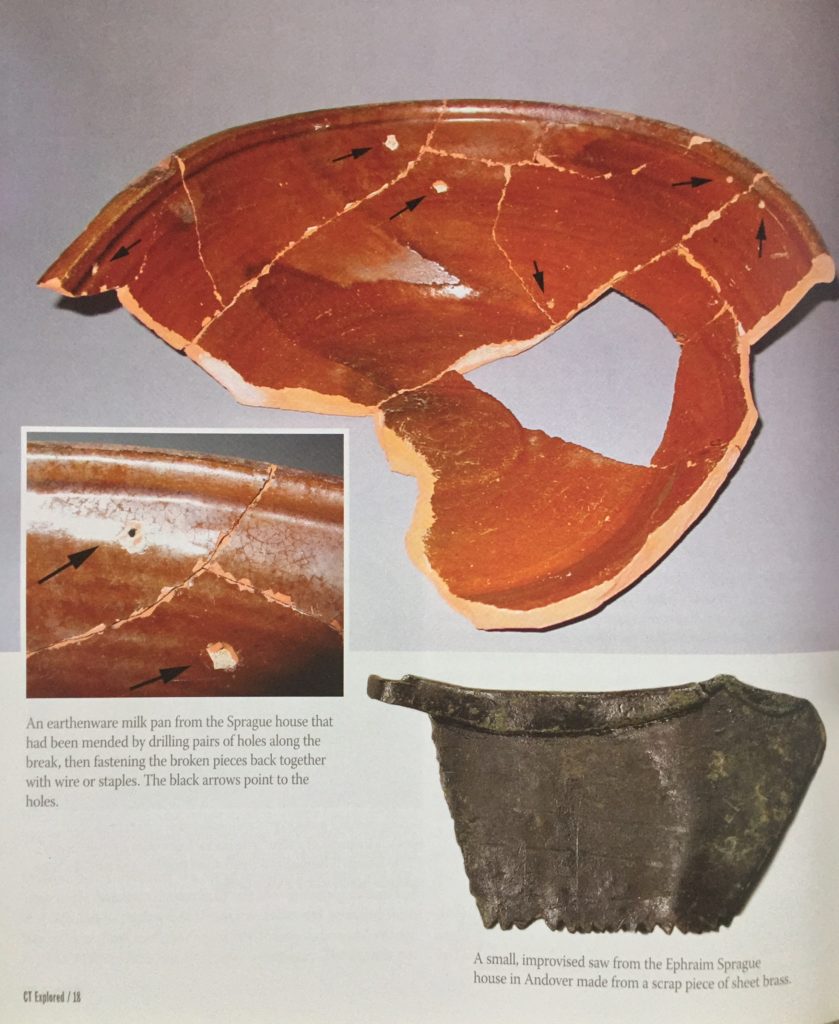

The discovery of black bear, fox, skunk, raccoon, beaver, and muskrat bones indicated the Spragues hunted for food and furs. They made their own musket balls and shot by casting molten lead in molds and by cutting lead scraps into cubes and pounding them into spheres. Lead was also shaped into fishing sinkers and pencils. A cache of deer antler had been sawn into pieces. The durable, yet highly workable qualities of antler made it ideal for making gunpowder measures and tool handles. Several of the earthenware vessels showed evidence of being broken and then repaired by drilling pairs of holes along the breaks and then fastening the pieces back together with wire or staples. Leaky brass kettles were repaired with improvised patches and rivets, and when they were too worn out to fix, they cut them up for other uses, including a small hand saw. An old drill bit was bent into a hanging hook and old pieces of sheet iron were cut and folded into a funnel and perforated to make a sieve. A number of the strike-a-lights used to make fire were recycled from worn out gunflints. Even the tobacco pipes showed signs of continued use. As pipe stems broke and became shorter and thicker, the ends or nibs were often ground down to fit more comfortably in the mouth until the hot pipe bowl was almost under the smoker’s nose!

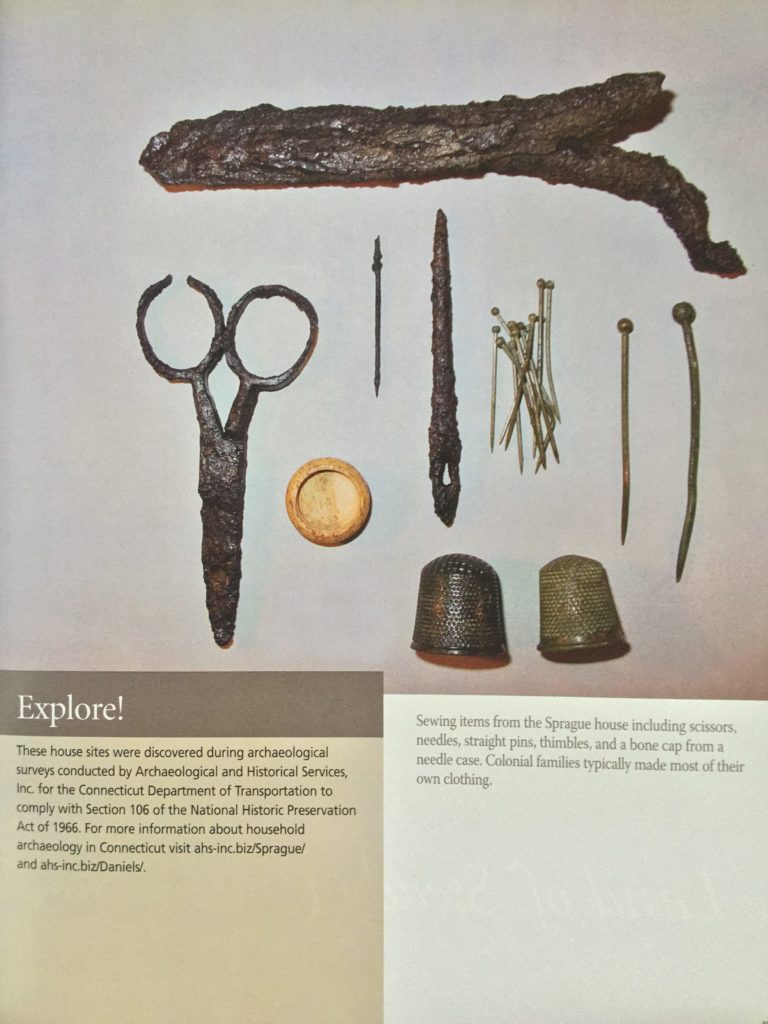

Most of the Spragues’ daily activities revolved around raising, harvesting, preserving, and preparing food. Along with evidence of butchering livestock and dairying, large quantities of carbonized corn, oats, and potatoes that had been burned and preserved by the house fire were found. Cellars were essential for storing barrels of salted beef and pork, beer, cider, and various fruits and vegetables, as they kept foods from freezing in the winter and cool in the summer. In one of the Spragues’ cellars, a series of round pits that they had dug into the floor were discovered. These were used to store and preserve root vegetables (potatoes, carrots, parsnips) through the winter by burying them underground. Families typically made most of their own clothing; scissors, needles, thimbles, and hundreds of straight pins were scattered throughout the Spragues’ house area.

Although the archaeology showed that the Spragues practiced sound household economy, the family also purchased fine tablewares and personal items, most of them made in England. Discovered among the ruins of the house were a complete white stoneware tea set, a hand-painted delftware punch bowl, and matching table forks and bone-handled knives made of iron. There were cufflinks engraved with floral and cornucopia motifs, relief-cast shoe buckles, and knee buckles embellished with glass gems. There were also brightly colored glass beads and both plain and decorated buttons made of brass, pewter, and glass. A few of Ephraim’s more sentimental possessions were revealed as he dictated his will on November 1, 1754, including his “best beaver hat,” a white muslin handkerchief, gloves, and a cane.

As archaeological excavations have been carried out at other colonial-period sites, similar patterns in household economy have emerged.

What would future archaeologists say about you if they discovered your household trash?

Ross K. Harper, Ph.D., is an archaeologist with Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. in Storrs.

Explore!

These house sites were discovered during archaeological surveys conducted by Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. for the Connecticut Department of Transportation to comply with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.. For more information about household archaeology in Connecticut visit

ahs-inc.biz/Sprague/ and ahs-inc.biz/Daniels/

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 13: Discovery: Connecticut’s Most Important Dig Ever

42 Minutes. Release Date: August 23, 2016

Take an earwitness journey to the 1659 John Hollister homesite on the Connecticut River in ancient Wethersfield, and join the archaeologists, graduate students, and volunteers from many walks of life as they uncover one of the richest early colonial sites ever found in Connecticut.

Summer 2014: History Underground

Guide to Images:

Sprague Brass Saw: A small, improvised saw from the Ephraim Sprague house in Andover made from a scrap piece of sheet brass.

Sprague milk pan repair: An earthenware milk pan from the Sprague house that had been mended by drilling pairs of holes along the break, then fastening the broken pieces back together with wire or staples. The black arrows point to the holes.

Sprage Sewing Items: Sewing items from the Sprague house including scissors, needles, straight pins, thimbles and a bone cap from a needle case. Colonial families typically made most of their own clothing.

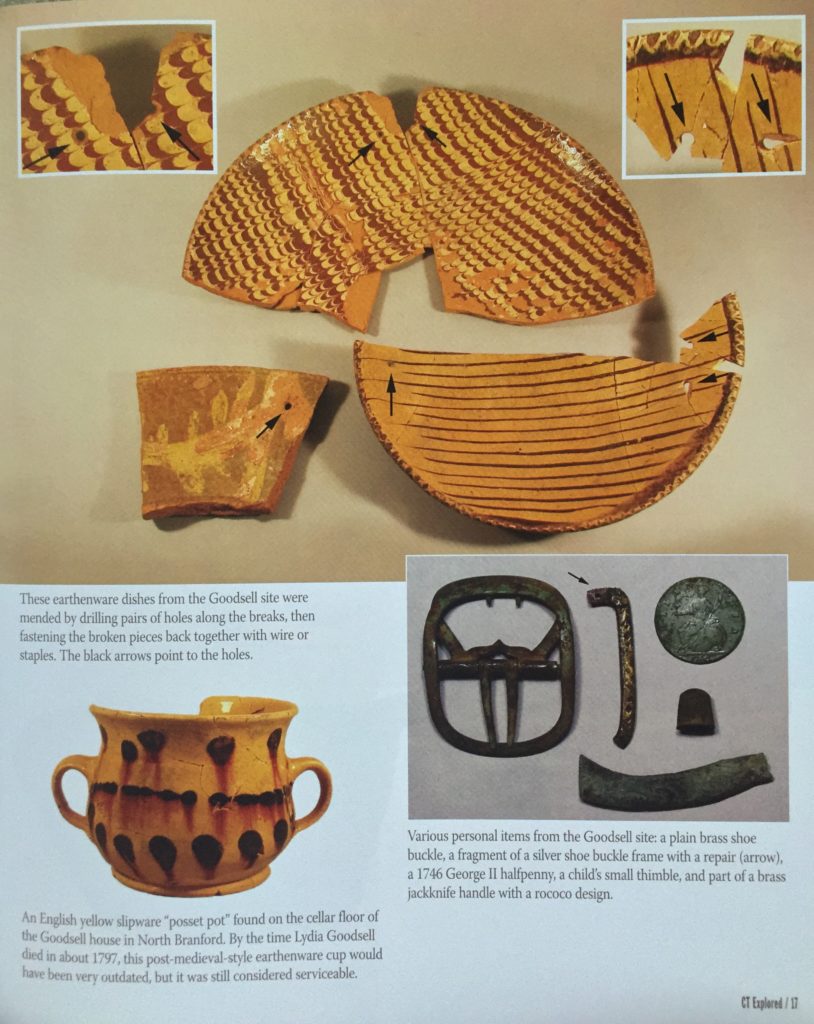

Goodsell posset pot: An English yellow slipware “posset pot” found on the cellar floor of the Goodsell house in North Branford. By the time Lydia Goodsell died in about 1797, this post-medieval-style earthenware cup would have been very outdated, but it was still considered serviceable.

Goodsell Ceramics Repairs: These earthenware dishes from the Goodsell site were also mended by drilling pairs of holes along the breaks, then fastening the broken pieces back together with wire or staples. The black arrows point to the holes.

Goodwill accouterments: Various personal items from the Goodsell site: a plain brass shoe buckle, a fragment of a silver shoe buckle frame with a repair (arrow), a 1746 George II halfpenny, a child’s small thimble, and part of a brass jackknife handle with a rococo design.

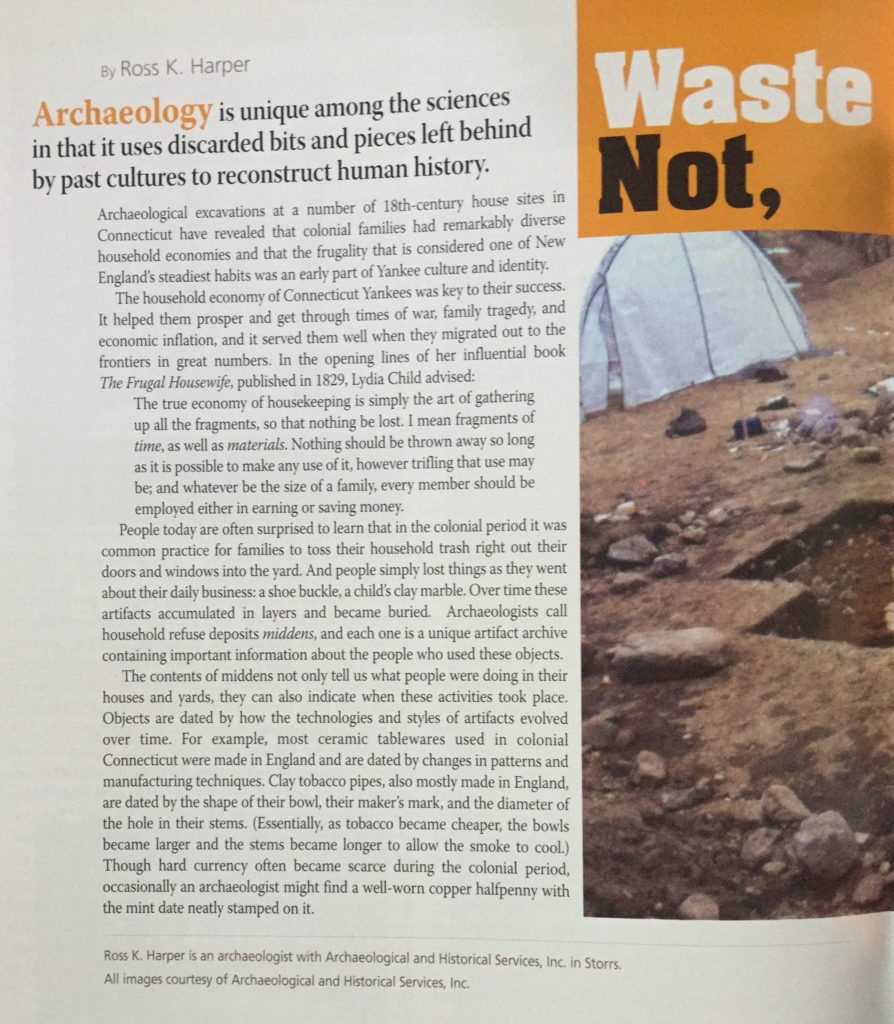

Daniels Cellar: The Daniels house in Waterford during excavation, showing the stone-lined cellar hole that had been buried in a field. Beyond the cellar is a highway entrance ramp that was built over a colonial-era road. The white tent in the background had been placed over the cellar so it could be excavated in the winter.

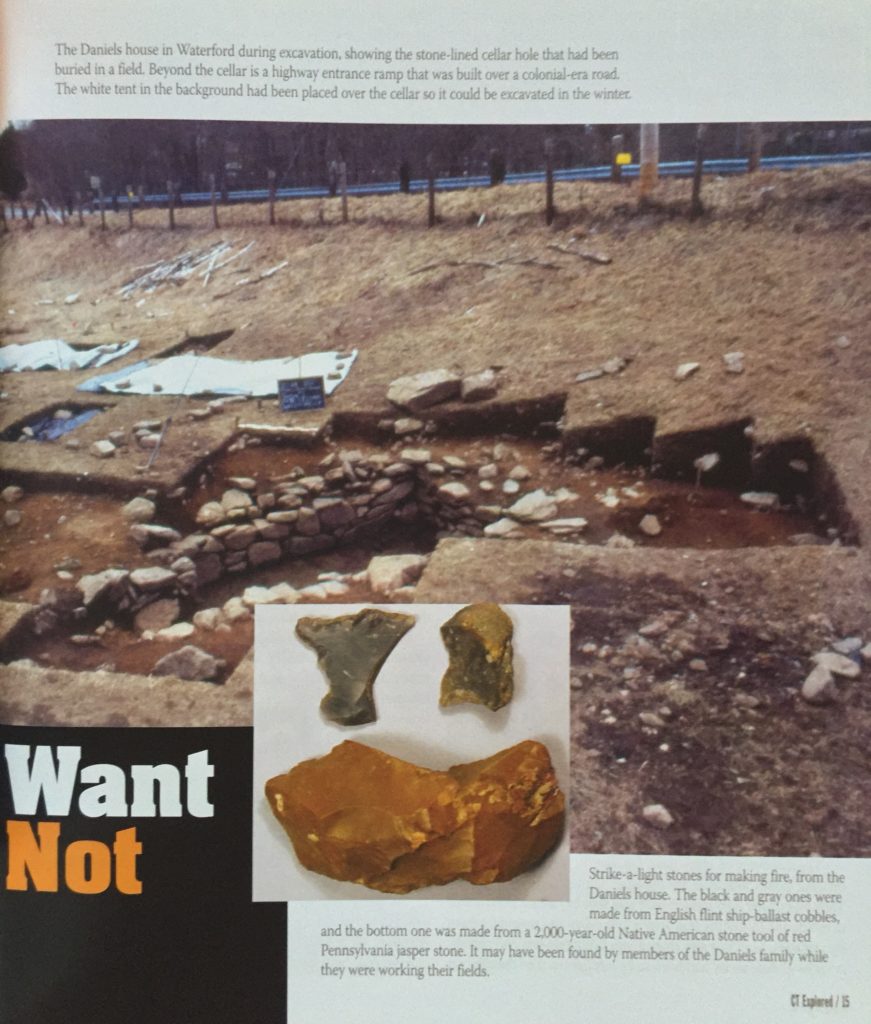

Daniels flint strikers: Strike-a-light stones for making fire, from the Daniels house. The black and gray ones were made from English flint ship-ballast cobbles, and the bottom one was made from a 2,000-year-old Native American stone tool of red Pennsylvania jasper stone. It may have been found by members of the Daniels family while they were working their fields.