By Amy Northrop Wittorff and Frank G. Winiarski

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2016

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

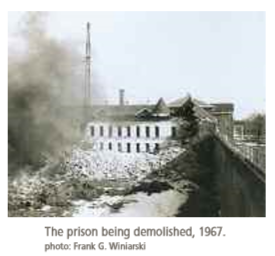

Wethersfield, Connecticut, founded in 1634, is known as the state’s “most auncient town.” That name calls to mind Wethersfield’s quaint historic district, sleepy cove, and lush suburban lawns. Few remember that it was home to the state’s main prison for 136 years, a distinction that was originally a point of pride. The prison made its mark on the development of the town throughout the 19th and into the 20th century before it was torn down in 1967.

Wethersfield, Connecticut, founded in 1634, is known as the state’s “most auncient town.” That name calls to mind Wethersfield’s quaint historic district, sleepy cove, and lush suburban lawns. Few remember that it was home to the state’s main prison for 136 years, a distinction that was originally a point of pride. The prison made its mark on the development of the town throughout the 19th and into the 20th century before it was torn down in 1967.

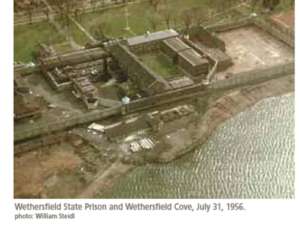

In the early years of Connecticut the only state or colony facility for housing prisoners was the New-Gate Prison in East Granby (then Simsbury), where convicts were held underground in a former copper mine. By the early 19th century, New-Gate was considered expensive and inhumane, and plans were begun to construct a new state prison. Many towns vied to be the site of the new prison, but Judge Martin Welles of Wethersfield succeeded in convincing the state legislature to award it to his hometown. His arguments included Wethersfield’s proximity to the state capital, Hartford, easy access to the Connecticut River for transporting building materials and goods, and local clay to make bricks, which was the proposed prison industry. In May and June 1826 the State house and senate approved the location, and land along Wethersfield’s Cove was purchased from several local landowners including Justus Riley and the Welles family (Judge Martin Welles among them.) Ground was broken for the construction of the main prison building, which included the four-story cell block, the Warden’s residence, and the Women’s Department on July 1, 1826.

Twenty inmates were brought from New-Gate to construct the prison buildings in June 1827, and another 20 in August. On September 29, 81 inmates joined them, for a total workforce of 121 prisoners. Among them were four women and Prince Mortimer, an African-American prisoner who was 103 years old. Moses Pillsbury of New Hampshire was named the warden.

The Penitentiary System

Wethersfield State Prison was considered to be a place of rehabilitation, not punishment. As with several other newly established penitentiaries in the early 19th century, including Maryland Penitentiary in Baltimore, Sing-Sing in New York, and the Charlestown State Prison in Boston, it adhered to the Auburn system of corrections in which prisoners worked in workshops during the day and spent their nights in solitary confinement in their cells. Meals were taken in the cells, and strict silence was enforced at all times to give prisoners the social solitude to reflect on their crimes. Each day groups of 10 prisoners were marched to and from the workshops in lockstep, meaning each inmate placed his hand on the shoulder of the inmate in front of him, the entire line marching together, eyes facing forward at all times. Wethersfield State Prison attracted tourists who came to see the prisoners walk in lockstep and to view their workshops and accommodations. Charles Dickens was among these visitors in 1842.

French political author and historian Alexis de Tocqueville visited the institution in 1831 and in his 1833 On the penitentiary system in the United States and its application in France (co-written by Gustave de Beaumont) called it a model institution among the “good” prisons (referring to the Auburn System)—“if it is not the best.” Tocqueville further commented, “As soon as the penitentiary system was adopted in the United States, the personnel changed its nature. For a jailor of a prison, vulgar people only could be found; the most distinguished persons offered themselves to administer a penitentiary where a moral direction exists.”

Prison Construction

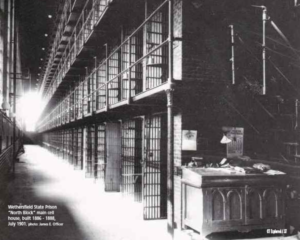

The first building completed was the main cell block: a four-story cell house 48 feet wide and 177 feet long consisting of 136 cells for 136 prisoners. The brownstone for the walls came from Portland, Connecticut and the iron bars from Salisbury, Connecticut. Cells were 3½ feet wide, 7 feet long, and 7 feet high. They were furnished with a plank bed that folded up to the wall, a straw mattress, and a slop bucket. The cell doors were made of 3½-inch-thick oak boards. The cell house was heated by two stoves, one on either end of the cell block, and water was drawn from two wells in the prison yard. By 1830 the prison population had already outgrown the facility; an addition to the main hall building provided 64 new cells, a kitchen, and a new wall that created an enclosed yard that included the two wells that provided water to the prison. In 1835 another 16-cell addition created space to house maximum-security and insane prisoners. This would be the pattern for the next 100 years as the State of Connecticut struggled to construct and modernize prison facilities to accommodate the rapid growth of the prison population.

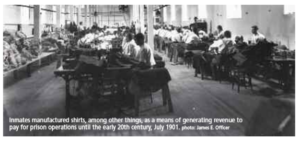

The prison’s workshops produced a variety of goods including shoes, boots, clothing, furniture, pewter “Britannia Ware,” clock parts, spectacles, canned goods, and firearms. The prison had a contract with the Hitchcock Chair Company from 1828 to the 1840s. Male inmates made the chairs, and female inmates wove the rush or cane seats. During the early 20th century the workshops included a machine shop, sign shop, paint shop, rug shop, and concrete shop. The ventures allowed the prison to fund itself and return a profit to the state.

Violence and Poor Management

As de Tocqueville marveled at the low cost of operating the prison and the fact that its prolific workshops turned a profit for the State of Connecticut, he did not see the abuse of prisoners and mismanagement of the prison that may have been occurring at that time. In 1832 Judge Welles, a prison director, accused then-warden Amos Pillsbury (son of the first warden Moses Pillsbury) of denying prisoners medical care, diverting their food to the warden’s own family kitchen, and failing to adequately heat the buildings, among other accusations. Pillsbury was removed for nine months (1832-1833) but was reinstated to his position. Welles ended his service on the prison board in 1833.

Just two years after de Tocqueville’s visit, the prison experienced its first violence. On April 30, 1833, night watchman Ezra Hoskins was murdered by three inmates in their unsuccessful escape attempt. On September 12, 1835, inmate Harvey Griswold attempted to murder Pillsbury by stabbing both him and a guard with a knife but only succeeded in wounding them. Other wardens were not so fortunate. N. Daniel Webster, warden from 1857 to 1862, and his replacement William Willard were both murdered by inmates, in 1862 and 1870, respectively. A total of two wardens and four guards were killed by prisoners during the 136 years of the prison’s existence.

Overcrowding and Executions

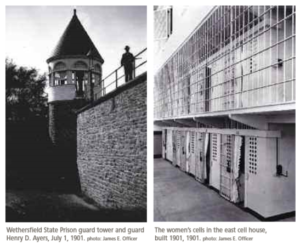

In 1872, the prison commission recommended building a new prison at a new site, but the legislature rejected the plan, calling instead for upgrading the existing facility. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Wethersfield State Prison saw repairs and improvements to infrastructure, including the introduction of steam heat, improved ventilation, a toilet and sink in each cell, better drainage, and 83 new cells. In 1886 construction began on a brick, 396-man cell house, steam boiler house, kitchen, chapel, and laundry. The prison could now accommodate up to 480 prisoners.

In 1893 a state law passed requiring the state prison to handle the execution of condemned prisoners. Before then all executions in Connecticut were carried out by the county governments and were open to the public. In 1894 the gallows house was built, and John Cronin became the first of 55 men to be executed by hanging there. Hanging was the official means of execution in Connecticut until it was abolished in May 1936.

Bodies of deceased prisoners that were not claimed by their families or sent to Yale Medical School were interred in the prison cemeteries, which still exist in the northeast corner of Cove Park. Burials had taken place there since 1828, on a high knoll overlooking the cove just 2½ feet below the surface. Complaints about buried bodies resurfacing in 1888 led to a new prison cemetery’s being laid out adjacent to the old one, with burials now deeper at six feet. An estimated 60 to 80 bodies are buried there, including those of the indigent and victims of the 1847 typhus fever epidemic. Several Civil War veterans are among those interred there.

Bodies of deceased prisoners that were not claimed by their families or sent to Yale Medical School were interred in the prison cemeteries, which still exist in the northeast corner of Cove Park. Burials had taken place there since 1828, on a high knoll overlooking the cove just 2½ feet below the surface. Complaints about buried bodies resurfacing in 1888 led to a new prison cemetery’s being laid out adjacent to the old one, with burials now deeper at six feet. An estimated 60 to 80 bodies are buried there, including those of the indigent and victims of the 1847 typhus fever epidemic. Several Civil War veterans are among those interred there.

Improvements to the prison continued and cells were added through the early 20th century. On Christmas Day 1901 the dining hall opened, along with a steel cell block that by 1931 contained 248 cells, including a special section for women. Female prisoners were allowed curtains, carpets, and even pet birds. They were guarded by a matron who lived in a room above the cell block.

Change in the 20th Century

Major changes in the prison’s system of discipline occurred in the 20th century. In 1914 the Auburn system was abolished, as was the system of financing the prison through the revenue generated by prison labor. Responding to labor-union pressure, in 1927 the legislature passed laws dictating that all revenue from prison labor go to the state, and the prison became dependent on appropriations. Reports thereafter complained of chronic underfunding. The federal Hawes-Cooper Act of 1934 addressed the unfair nature of contract labor in prisons and effectively prohibited prison-made goods from being sold. This ended lucrative contracts such as one with the New York Shirt Company. The prison administration partly made up for this by producing goods for the state such as license plates, highway signs, concrete construction barriers, and printing. The prison’s shirt shop closed and was replaced by smaller shops for concrete work, tailoring, canning goods from the Osborn Farm (an off-site, low-security correctional institution in Somers that opened in May 1931).

The electric chair replaced hanging as the means of execution in 1936. Joseph McElroy of New Haven was the first of 18 men to be executed by electrocution between 1937 and 1960. These executions were carried out in an execution chamber near the prison hospital and machine shop.

Advantages to the Town of Wethersfield

The prison’s presence in Wethersfield allowed the town to become one of the first of Hartford’s suburbs to receive the modern conveniences of transportation, communication, and utilities. The Hartford & Wethersfield Horse Railway began operating in 1863, with prisoners laying the track along State Street. When the trolley was electrified in 1897, power was also brought to the prison and Wethersfield became one of the earliest Hartford suburbs to expand electricity to private homes. Public water came to town when fire hydrants and water pipes were installed and the first public water main was run to the prison in 1869. Throughout the prison’s existence in Wethersfield, privileged low-risk prisoners (called trustees) performed the duties of a public works department, cleaning and maintaining the streets, removing snow, and repairing storm damage—including that caused by the 1936 flood and 1938 hurricane—to roads, bridges, and public buildings.

The Final Chapter

Crowded conditions along with work demands on prisoners associated with production quotas for the New York Shirt Company contract led to a sit-down strike in 1913; two more strikes in 1918.proteseted work quotas and poor food quality. In 1919 a prisoner was killed in an uprising in the shirt and shoe shops. A spittoon was thrown, and guards fired their pistols, mortally wounding the prisoner, Louis Brown, who was thought to have thrown the object. In 1929 a planned uprising was deterred by the planned use of planes with machine guns on standby at nearby Brainard Field. Prisoners heard of this preparation, and no uprising took place.

By the mid-1950s the prison was overcrowded and lacked adequate recreation and rehabilitation facilities for its inmates. In February 1956, 200 to 300 prisoners (about a third of the population) participated in a sit-down strike to protest poor food quality, lack of recreation, and unfair parole policies. Prisoners also demanded a better movie screen. On July 28 the entire 700- to 750-member prison population gathered in the recreation yard and refused to return to the cells. Warden George Cummings was pelted with rocks and resigned on the spot, at about 2 a.m. U.S. Army Lt. General Frederick G. Reincke took over as acting warden to restore order and institute rehabilitation programs.

In 1958-1959, more than 1,000 prisoners were housed at the prison. The prison cannery was converted to a dormitory for 60 to 70 “trustees,” who also slept in cell-block corridors and in the laundry. A Quonset hut was also set up in the prison yard to house prisoners. On January 6, 1960, 400 inmates staged a riot in the east and north cell blocks. The Wethersfield Fire Department brought in fire hoses, and state police tear-gassed rioting prisoners. Extensive damage was done to the north cell block. In the wake of the riot Governor Abraham Ribicoff ordered expedited construction of new prison facilities in Enfield and Somers. Three years later, 793 prisoners were moved to Somers, and the Wethersfield prison ceased operations.

In 1958-1959, more than 1,000 prisoners were housed at the prison. The prison cannery was converted to a dormitory for 60 to 70 “trustees,” who also slept in cell-block corridors and in the laundry. A Quonset hut was also set up in the prison yard to house prisoners. On January 6, 1960, 400 inmates staged a riot in the east and north cell blocks. The Wethersfield Fire Department brought in fire hoses, and state police tear-gassed rioting prisoners. Extensive damage was done to the north cell block. In the wake of the riot Governor Abraham Ribicoff ordered expedited construction of new prison facilities in Enfield and Somers. Three years later, 793 prisoners were moved to Somers, and the Wethersfield prison ceased operations.

In 1962 the Connecticut Department of Motor Vehicles built a facility on the south lawn of the prison. The prison was torn down in 1967. Some local officials campaigned to keep the original Greek revival portion of the prison, but to no avail. The land that is now Cove Park and the Solomon Welles House, which served as the warden’s home from 1900 to 1963, was leased to the Town of Wethersfield for 99 years.

Few traces of the old prison remain: just the flagpole, prison cemetery, cannery, pump house, and garage buildings. Today they go largely unnoticed by the many people who come to do business at the Department of Motor Vehicles or enjoy an event at the park. The prison has, however, left a lasting legacy in the development of the town and in the memories of Wethersfield residents who lived and worked in the shadow of its walls.

Information for this article was gleaned from wardens’ reports, directors’ reports, the Hartford Daily Times and the Connecticut Courant, housed at the Connecticut State Library, the Hartford Public Library, and the Wethersfield Historical Society library.

Amy Northrop Wittorff is executive director of Wethersfield Historical Society. Frank Winiarski is a local historian and Wethersfield State Prison expert.

Explore!

Castle on the Cove: the Connecticut State Prison and Wethersfield, on view through 2017. Wethersfield Historical Society, Keeney Memorial Cultural Center, 200 Main Street, Wethersfield. Wethersfieldhistory.org, 860-529-7656

Cove Park, access via Main Street and State Street, Wethersfield

110 acres on Wethersfield Cove with a boat launch with access to the Connecticut River, park grounds, ball fields, picnic areas, and a soccer field off State Street. Wethersfieldct.com

Read:

“Escape from New-Gate Prison,” Summer 2006. www.ctexplored.org/escape-from-new-gate-prison/