By Chris Pagliuco © Connecticut Explored Winter 2007/08

Connecticut’s 17th-century witch trials have long been overshadowed by the more numerous and better publicized proceedings in Salem, Massachusetts. But Connecticut’s were among the first such trials in New England, preceding Salem’s by four decades. And Mary Johnson’s 1648 confession of witchcraft in Wethersfield was the first of its kind in the colonies.

In all, Connecticut heard 43 witchcraft cases, with 16 of these ending in execution. And Wethersfield, with nine documented accusations and three executions between 1648 and 1668, is where the story begins.

Wethersfield’s “witches” were victims of both their neighbors and their times. In the first case, that of Mary Johnson, there was no trial, or even a documented accusation, because Johnson confessed under pressure from Reverend Samuel Stone. Three years later Johnson’s 1648 execution, John and Joan Carrington, a married couple, were accused of and executed for witchcraft. Even less is known about this couple or the circumstances surrounding their ordeal. An inventory of the Carrington estate, completed in 1653, revealed the value to be a paltry 23 pounds, 11 shillings. (Their debts further cut that value in half.)

Wethersfield’s “witches” were victims of both their neighbors and their times. In the first case, that of Mary Johnson, there was no trial, or even a documented accusation, because Johnson confessed under pressure from Reverend Samuel Stone. Three years later Johnson’s 1648 execution, John and Joan Carrington, a married couple, were accused of and executed for witchcraft. Even less is known about this couple or the circumstances surrounding their ordeal. An inventory of the Carrington estate, completed in 1653, revealed the value to be a paltry 23 pounds, 11 shillings. (Their debts further cut that value in half.)

Documentation of Connecticut’s witch history is slim, so piecing the story together is challenging. In Wethersfield, more than 300 years after the fact, the line between legend and reality is particularly blurred because many court records are incomplete or missing altogether, and those that do exist offer severely biased accounts. Since the overwhelming majority of the victims were poor and often transient, most did not leave any personal belongings for historians to study. In many instances the only documentation of the victims’ very existence comes from the trials themselves.

Ironically, the most prominent source of information about Wethersfield’s witchcraft history is also the source of much misinformation. Elizabeth George Speare’s 1958 classic The Witch of Blackbird Pond, now a middle-school reading-list staple, vividly describes the Wethersfield meadows and cove and several real people from the time, making the novel seem biographical. While thoroughly researched and beautifully written, Speare’s book is in fact a work of fiction and not an authoritative source. In the novel, for instance, the witch of Blackbird pond is a Quaker. While Quakers were certainly viewed as dissidents, they were not persecuted in Connecticut as witches. Yet most readers would never think to question such a point. And so the line between fact and legend grows blurrier.

Ironically, the most prominent source of information about Wethersfield’s witchcraft history is also the source of much misinformation. Elizabeth George Speare’s 1958 classic The Witch of Blackbird Pond, now a middle-school reading-list staple, vividly describes the Wethersfield meadows and cove and several real people from the time, making the novel seem biographical. While thoroughly researched and beautifully written, Speare’s book is in fact a work of fiction and not an authoritative source. In the novel, for instance, the witch of Blackbird pond is a Quaker. While Quakers were certainly viewed as dissidents, they were not persecuted in Connecticut as witches. Yet most readers would never think to question such a point. And so the line between fact and legend grows blurrier.

Yet despite the dearth of evidence and though still cloaked in mystery, the story of Wethersfield’s witch accusations is important to understanding 17th-century Connecticut.

Fear and Instability

Those accused of witchcraft were thought to have signed a compact with the devil, choosing him over God and thereby gaining supernatural powers. A person exhibiting pride, discontent, greed, and lying risked being believed a witch. People despised witches on moral and religious grounds but also had practical reasons to fear them: chief among a witch’s powers was maleficium, or the ability to harm others by supernatural means.

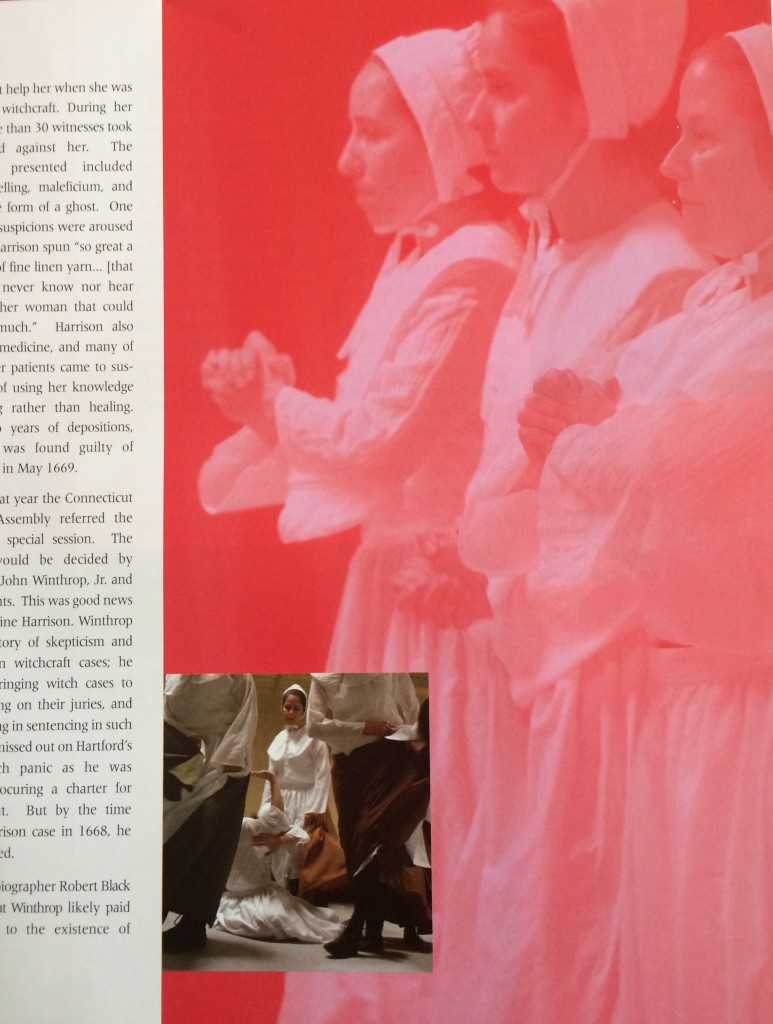

Image courtesy of Judy Dworin Performance Project Inc. from “The Witching Hour,” 2007. photos: Nick Lacy

How could the Puritans, whose culture emphasized education and prudence, have believed such outlandish notions? According to Yale historian John Demos, “Fear was an elemental part of life in all the new settlements” and created an environment that fostered witchcraft accusations. Wethersfield residents, for their part, had plenty to fear. They could lose their sheep and other farm animals to wolf and bear attacks. The Connecticut River could flood at any time, wiping out crops. Epidemics visited the region in 1647 and1648, killing dozens of townspeople in an already small and unstable population. The local Native Americans were equally dangerous. The Pequot War began with a “massacre” in Wethersfield in 1637; nine Wethersfield residents were killed, two captured, and the entire population horrified. (Some Wethersfield residents got their revenge weeks later with the slaughter of hundreds at the Pequot Massacre in Mystic.)

Even the elements of society that were supposed to lend stability to the community were in turmoil. Religious controversy dominated Wethersfield throughout the 1640s and 1650s. While details of the conflict are vague, the seriousness of the strife is suggested by large numbers of settlers fleeing Wethersfield for the newer towns of Guilford, Stamford, Branford, and other settlements. During the 1650s, members of a Puritan congregation in town sought to remove their minister, a move that led to the exodus of more than half the church members to Hadley, Massachusetts. (This local conflict was part of a greater regional dispute called the Hartford Controversy.) In this context of uncertainty and flux came the first accusations of witchcraft in New England.

The instability of life in colonial Connecticut created a need for order. A theme that connects those accused of witchcraft is that they each had challenged the social orthodoxies of their communities, thus rocking the boat and making their neighbors uneasy. In some ways, witch accusations served as a form of social release during these difficult times, and the community’s more vulnerable members made easy scapegoats. Many of the accused were economically vulnerable or had been convicted previously of thievery or other similar offenses. All three of Wethersfield’s “witches” who were executed, Mary Johnson and Joan and John Carrington, are notable for their lack of wealth and social standing. About a decade later, another poor couple, Katherine Palmer (who had been accused of witchcraft) and her husband Henry, fled during the Hartford witch panic.

Others accused of witchcraft, though not poor, were unconventional, and even contentious figures who challenged the proper order of society in the young Puritan colony. James Wakeley, sometimes attributed to Hartford, went to court 37 times within a 20-year period, half the time representing the prosecution and half the time the defense. Wethersfield’s last convicted witch, Katherine Harrison, may have been reviled for her rapid ascension to wealth. As a young woman, Harrison was a servant to a prominent family in Hartford. By the time her husband, a farmer, died, she had inherited from him an estate valued at nearly a thousand pounds. Within months of her husband’s death, an onslaught of lawsuits and accusations against Katherine began.

Analysis of church and court records reveals that women of the period identified weakness and a proclivity toward sin as chief characteristics of their gender. And historian Elizabeth Reis explains that while men were more confident in their ability to withstand the devil’s temptation, “Women were more likely to interpret their own sin, no matter how ordinary, as a tacit covenant with Satan.” No matter how horrifying the prospect, “A good Puritan woman/witch needed to repent [for her sins]….”

Mary Johnson likely was guided by this line of thinking. A house servant, she had two years earlier (first in Hartford and then in Wethersfield) been convicted of thievery and whipped. In her confession, she revealed that she was discontent with her many chores and that “…a devil was wont to do her many services.” To the Puritans the term discontentment meant “thinking oneself above one’s place in the social order,” according to Carol Karlsen in her book The Devil in the Shape of a Woman (Norton, 1998), a sentiment Johnson’s confession clearly reflects. Later in her confession Johnson also admitted to having killed a child and committed adultery. While no other mention of that child is known, Johnson was apparently pregnant when convicted, and her execution was delayed until her own child was born. It was determined that her newborn baby would be raised by her prison keeper’s son until the child reached turned 21.

Image courtesy of Judy Dworin Performance Project Inc. from “The Witching Hour,” 2007. photos: Nick Lacy

“Diabolical Possession”

In 1662, several Wethersfield residents were implicated in the Hartford witchcraft hysteria, the first widespread witch panic in New England history. Two separate but equally disturbing incidents triggered the panic: the “diabolical possession” of Hartford resident Ann Cole and the fatal illness suffered by eight-year-old Elizabeth Kelly. Young Kelly’s damning last words “Goody Ayers chokes me!” were enough to set witch accusations flying. In all, eight people were formally charged; three, and possibly a fourth, were executed. Wethersfield residents Katherine Palmer and James Wakeley were both among the formally accused, yet neither was tried; both names appear in Rhode Island records shortly thereafter, suggesting they fled for their safety.

Elizabeth and John Blackleach of Wethersfield were also suspected of witchcraft during the panic, but formal charges were never filed, and they later counter-filed a slander case. Incredibly, despite what must have been an ordeal for them, the Blackleaches would next become accusers themselves, bringing charges against fellow Wethersfield resident Katherine Harrison.

The trial of Katherine Harrison provoked a major revision of Connecticut trial law. According to Connecticut state historian Walter Woodward, Harrison’s was “the pivotal case in the transformation of colonial witch craft prosecution” from reliance on single-witness testimony to requiring multiple and corroborating testimonies.

Harrison apparently was known for having difficult relationships with her neighbors, a situation that didn’t help her when she was tried for witchcraft. During her trial, more than 30 witnesses took the stand against her. The evidence presented included fortune telling, maleficium, and taking the form of a ghost. One woman’s suspicions were aroused because Harrison spun “so great a quantity of fine linen yarn… [that she]…did never know nor hear of any other woman that could spin so much.” Harrison also practiced medicine, and many of her former patients came to suspect her of using her knowledge for killing rather than healing. After two years of depositions, Harrison was found guilty of witchcraft in May 1669.

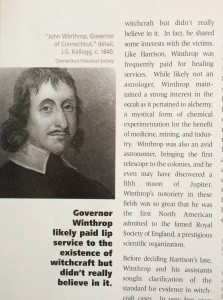

In May that year the Connecticut General Assembly referred the case to a special session. The verdict would be decided by Governor John Winthrop, Jr. and his assistants. This was good news for Katherine Harrison. Winthrop had a history of skepticism and restraint in witchcraft cases; he avoided bringing witch cases to trial, serving on their juries, and participating in sentencing in such cases. He missed out on Hartford’s 1662 witch panic in Hartford as he was abroad, procuring a charter for Connecticut. But by the time of the Harrison case in 1668, he had returned.

In May that year the Connecticut General Assembly referred the case to a special session. The verdict would be decided by Governor John Winthrop, Jr. and his assistants. This was good news for Katherine Harrison. Winthrop had a history of skepticism and restraint in witchcraft cases; he avoided bringing witch cases to trial, serving on their juries, and participating in sentencing in such cases. He missed out on Hartford’s 1662 witch panic in Hartford as he was abroad, procuring a charter for Connecticut. But by the time of the Harrison case in 1668, he had returned.

Winthrop biographer Robert Black surmises that Winthrop likely paid lip service to the existence of witchcraft but didn’t really believe in it. In fact, he shared some interests with the victims. Like Harrison, Winthrop was frequently paid for healing services. While likely not an astrologer, Winthrop maintained a strong interest in the occult as it pertained to alchemy, a mystical form of chemical experimentation for the benefit of medicine, mining, and industry. Winthrop was also an avid astronomer, bringing the first telescope to the colonies, and he even may have discovered a fifth moon of Jupiter. Winthrop’s notoriety in these fields was so great that he was the first North American admitted to the famed Royal Society of England, a prestigious scientific organization.

Before deciding Harrison’s fate, Winthrop and his assistants sought clarification of the standard for evidence in witchcraft cases. In very few cases was there physical evidence of verifiable offenses, leaving only “spectral evidence” to determine a case. Spectral evidence, or evidence pertaining to ghosts, spirits, dreams, or other visions in the absence of a body, was, of course, hearsay and therefore unreliable. Winthrop’s inquiry led to development of a set of standards that strengthened the evidentiary requirements for conviction. Among the new rules was one requiring that “a plurality of witnesses must testify to the same fact, ” a major shift that placed more burden on the prosecution than the defense.

The Harrison case marked a change in Connecticut magistrates’ approach that had been brewing for some time, as many shifted from being witch hunters to witch skeptics. Harrison’s death sentence was overturned, and she was released with the recommendation that, for her own safety, she leave town. Accusations, trials, and even convictions would continue for several more decades, including a second Connecticut panic, in Fairfield, but never again would a witch be executed in the state of Connecticut.

Christopher Pagliuco is a high school history teacher in Madison, Connecticut, town historian for Essex, and member of the CT Explored editorial team. He is author of The Great Escape of Edward Whalley and William Goffe: Smuggled through Connecticut (History Press, 2012).