(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

The year was 1850; the place, Hartford, Connecticut. On the grounds of the American Asylum (now the American School for the Deaf in West Harford), alumni from across the Northeast had assembled to present a suitably inscribed silver pitcher and salver to the school’s two surviving founders, Thomas H. Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc. (The third, Dr. Mason F. Cogswell, had died in 1830.) As an expression of gratitude for the establishment of the first successful school for deaf persons in America and for its several “daughter” schools, alumnus Thomas Brown, a student from 1822 to 1827, signed the sentiments of the assembly quoted above.

The school had a modest beginning in April 1817, when it enrolled seven students ranging in age from 9 to 51. Its first quarters were rented rooms on Hartford’s Main Street. By the end of the school’s first year the student body had grown to 21, and the staff to 6, including a steward and 5 instructors Gallaudet and Clerc, among them. Encouraged by generous grants from the State of Connecticut in 1816 and the federal government in 1819, the nascent school was ready, by 1820, to erect its first building: a combination of classrooms and offices and a dormitory for an ever growing body of residential students from across the Northeast.

According to the journal of master mason and plasterer Phineas Shepard, work on the building began in April 1820, with hopes of its being occupied in the autumn. A composition by a student dated March 26, 1821 noted the project’s delay to the following spring. An unidentified student wrote, “I believe that we shall remove to the new asylum in the spring… a very commodious, large and handsome building on Lord’s Hill. I think that we shall be very happy to live there.”

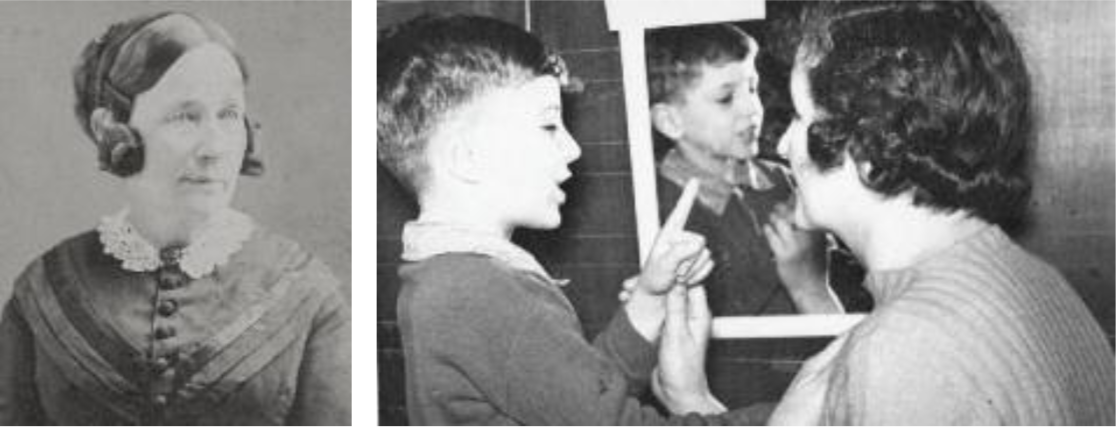

The importance of living quarters for students could hardly be underestimated. From the school’s very beginning, many of its students have come from out of state and spent from 2 to 5 (and in recent times up to 12 or more) years at the school. It became for them a second home and a vital cultural community. Staff, such as long-term matron Phoebe White, helped to create a homey atmosphere. As student John Burpee wrote in a tribute in 1846, “Mrs. White is the matron. How kind she is, and has charge of the pupils as a mother has of her children. They love her.”

(lef) Phoebe White who from 1839 to 1871 had charge of the girls who boarded at the schools; (right) A student in speech class learning how words are formed, c. 1945. The American School for the Deaf, Museum Archives

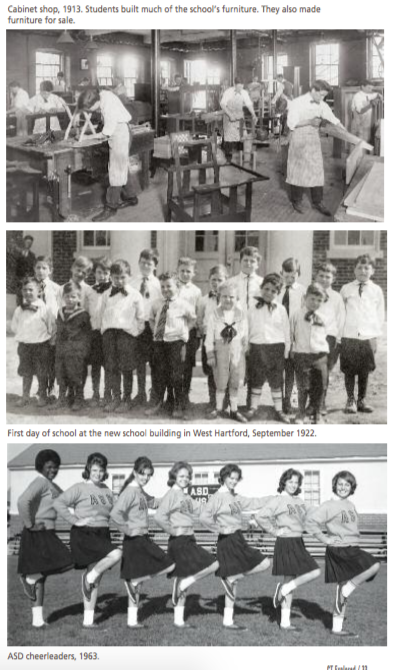

At first the students’ day chiefly involved learning communication skills and religious instruction, but thanks to a forward-looking administration, this rather restricted curriculum was soon expanded. Vocational training was added to the school’s curriculum in 1821. Woodworking, tailoring, shoemaking, and printing soon followed, making ASD the first school in Connecticut to include practical vocational education as a regular part of its curriculum. Academic subjects, French and geography among the first, were added as it became evident that not all students were destined to pursue trades. The school’s second student, George Loring, was a good example. He was not only bright and intellectually curious, he was the son of a wealthy Boston mercantile family. By 1852 the student body included enough such students to warrant the establishment of an academic high school.

(top) Cabinet shop, 1913, (middle) First day of school, 1922, (bottom) ASD cheerleaders, 1963. The American School for the Deaf, Museum Archives

At its founding, few students under age 12 were admitted. Thanks to the experiences of such imaginative teachers as David Bartlett, who taught from 1828 to 1832 and again from 1860 until his death in 1879, however, it became evident that the development of communication skills was best begun at a much earlier age. As a result, the age of admission was gradually lowered. For more than 30 years, ASD’s “Birth-to-Three” program has been providing year-round services to infants and young children who are deaf or hard of hearing and their families.

Today the school supports a full K-12 academic program and post-graduate training for students wishing to acquire additional vocational skills. Ever responsive to developments in educational philosophy and communication technology, the school has consistently pioneered new programs for enhancing its students’ experience. And under the leadership of Edward Peltier, a new building, eminently suited to the new era, has replaced the old, thus equipping the school to launch a third century of service to the deaf community.

Gary E. Wait was the archivist for the American School for the Deaf from 2000 to 2012. He wrote “American School for the Deaf: The Mother School of Deaf Education,” Spring 2005.

Explore!

“The Mother School of Deaf Education,” Spring 2005

Read more about childhood and education our our TOPICS page.