By Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The sperm whale was designated the Connecticut state animal in 1975. Why do we have a state animal that’s not indigenous to the state or its coastal waters?

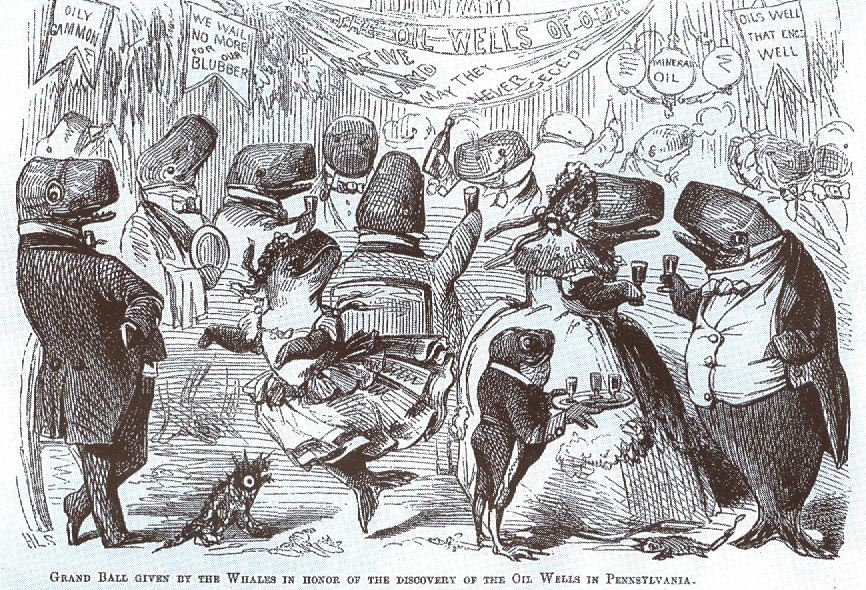

“Grand Ball Given by the Whales in Honor of the Discovery of the Oil Wells in Pennsylvania,” Vanity Fair, 1861

According to the State of Connecticut Web site, the sperm whale was chosen “because of its specific contribution to the state’s history and because of its present-day plight as an endangered species.” The site goes on to note that “during the 1800’s Connecticut ranked second only to Massachusetts in the American whaling industry. The sperm whale was the species most sought after by Connecticut whalers circling the globe on ships out of New London, Mystic and other Connecticut ports to bring back needed oil for lamps and other products.” As Edward Baker noted in discussing the War of 1812 (Hog River Journal, Summer 2012), that war “established—once and for all—the concept of ‘freedom of the seas,’ allowing Connecticut to expand, particularly its whaling industry. The industrial revolution could not have happened without a lubricant like sperm oil.”

Sperm oil was used in lamps and candles (it burns clear and bright and without smoke or odor) and as a lubricant in machinery (it can withstand high temperatures). Demand increased as the industrial revolution gained momentum and only went into decline with both the sharp drop in the whale population due to over-fishing and the invention of kerosene and alternative mineral- and petroleum-based lubricants in the mid-19th century. By the late 19th century, Connecticut was better known for its precision manufacturing than for its whaling industry.

Because whaling was so important to Connecticut, in this issue, we offer a trio of stories about the state’s 19th-century maritime trades. We note Mystic Seaport’s re-launch this summer of the restored 1841 Charles W. Morgan, the last extant wooden whaling ship; we tell the story of the related industry of sealing through the four-year round-the-world voyage of New Haven’s Joel Root and relate the adventures of Sarah Gray of Lebanon, who accompanied her whaling-captain husband Sluman Gray on five voyages. We also share Eliza Lydia McCook’s story. McCook left Connecticut on a venture of another sort to pursue the life of a missionary in turn-of-the-20th-century China during a time of political upheaval and great cultural change fueled in part by the Western hunger for trade. These stories remind us that Connecticut has been part of a global economy for more than 200 years.

Closer to home, we celebrate July 4th with the Bowens in 1870s Woodstock (where Independence Day events were attended by presidents and thousands of spectators), Frederick Gunn’s role in creating the concept of summer camps for kids, the 100th anniversary of Connecticut’s state parks, and Monte Cristo Cottage, the boyhood summer home of America’s only Nobel Prize-winning playwright, Eugene O’Neill.

Closer to home, we celebrate July 4th with the Bowens in 1870s Woodstock (where Independence Day events were attended by presidents and thousands of spectators), Frederick Gunn’s role in creating the concept of summer camps for kids, the 100th anniversary of Connecticut’s state parks, and Monte Cristo Cottage, the boyhood summer home of America’s only Nobel Prize-winning playwright, Eugene O’Neill.

Catch these Connecticans’ spirit of adventure and get out and explore! Summer is the time when most of Connecticut’s historic sites are open. Visit Mystic Seaport for the Morgan re-launch, the Butler-McCook House in Hartford to learn more about Eliza McCook, Roseland Cottage in Woodstock to see the Bowens family’s vintage July 4th decorations, or any of the 107 state parks. Check Spotlight, Afterword, and Heritage Hotspots for more ideas about what to do this summer.

Explore!

Real all of the stories from the Summer 2013 issue