By Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored inc. SUMMER 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

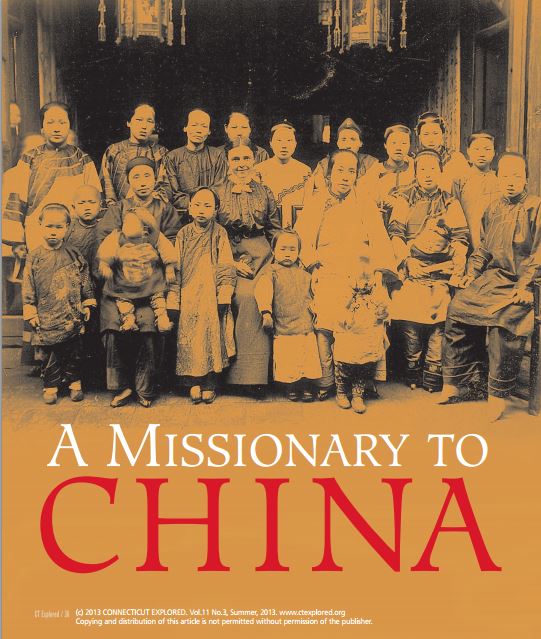

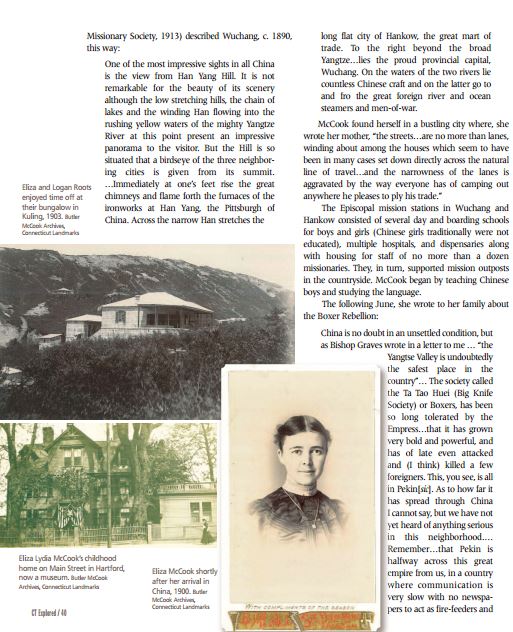

In October 1899, right around her 30th birthday, Eliza Lydia McCook left her Hartford home to serve as an Episcopal missionary in China. She traveled half way around the world to a country that was experiencing political unrest. The Boxer Rebellion—a nationalist, anti-foreign, and anti-Christian political movement—would, six months later, challenge the weak Qing dynasty and the growing foreign presence in China. Though the uprising was repelled with the assistance of the U.S. and seven other countries with interests in China, it was just the beginning of decades of political upheaval that at times threatened her safety. Still, McCook spent the rest of her life as a missionary there, marrying and raising a family. Her frequent letters home provide us with a window on life in central China in the first decades of the 20th century.

McCook was born in the family home on Main Street in Hartford (now the Butler-McCook House & Garden, a museum operated by Connecticut Landmarks) on October 22, 1869. She was the daughter of Episcopal minister and Trinity College professor John J. McCook and Eliza Butler McCook. Hers was a close-knit family that included four brothers and two sisters. After graduating from Hartford Public High School, she taught high-school English and French.

McCook’s decision to uproot herself from Hartford and move halfway around the world may have been influenced, according to Ruth Schloss in an article published in The Connecticut Antiquarian (June 1980), by Maria Huntington, “an older woman and experienced missionary” who accompanied her to China. McCook joined a missionary movement at its zenith—a movement that had for 70 years sent men and women around the globe to convert the local people to Christianity and to “improve” their lot through education and medical aid. Catholic and Protestant churches from a half dozen countries worked in China until the Communist takeover there in 1949.

As China slowly opened up to the West in the late 19th century, the American missionary force expanded rapidly. According to Jane Hunter in The Gospel of Gentility: American Women Missionaries in Turn-of-the-Century China (Yale University Press, 1984), the number of missionaries in China “more than doubled between 1890 and 1905, and by 1919 had more than doubled again, to thirty-three hundred workers.” The number of single women in missionary work, she notes, had never been higher, “perhaps because the women’s mission movement offered respectable careers even to the pious daughters of clergymen” such as McCook. Women (both single and married), Hunter further notes, constituted a majority of missionary volunteers in that era, causing concern among church leaders that men would turn away from missionary work as “women’s work” and ensuring that women would prove “to be particularly persuasive voices in the crusade for American influence in China.”

The McCooks were not happy with their daughter’s decision, according to Schloss. They worried about her health in a climate that was “cold and dank in winter and humid in summer” and where accommodations lacked central heating. Diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever, cholera, and tuberculosis were common.

The American Episcopal Church first sent missionaries to China in 1840 and by 1890 had established a medical school to train Chinese physicians in Shanghai, a college to train Chinese missionaries, and stations in four other cities (Wuchang, Hankow, Yantai, and Peking) that included churches, hospitals, and schools.

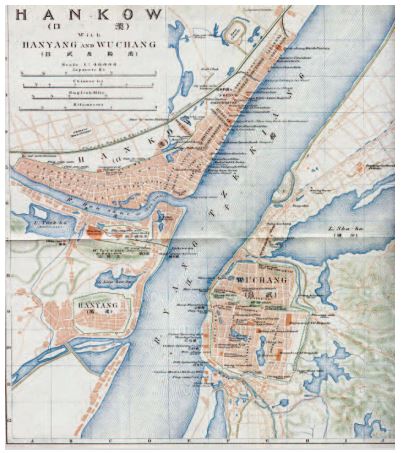

In December 1899, McCook arrived at the American Episcopal Mission in Wuchang (today Wuhan) in central China, more than 500 miles up the Yangtze River from the mission’s headquarters in Shanghai. It was an important junction on the railway from Peking (now Beijing) in the north to Guangzhou in the south. Missionaries Arthur Gray and Arthur Sherman in The Story of the Church in China (The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, 1913) described Wuchang, c. 1890, this way:

One of the most impressive sights in all China is the view from Han Yang Hill. It is not remarkable for the beauty of its scenery although the low stretching hills, the chain of lakes and the winding Han flowing into the rushing yellow waters of the mighty Yangtze River at this point present an impressive panorama to the visitor. But the Hill is so situated that a birdseye of the three neighboring cities is given from its summit. … Immediately at one’s feet rise the great chimneys and flame forth the furnaces of the ironworks at Han Yang, the Pittsburgh of China. Across the narrow Han stretches the long flat city of Hankow, the great mart of trade. To the right beyond the broad Yangtze…lies the proud provincial capital, Wuchang. On the waters of the two rivers lie countless Chinese craft and on the latter go to and fro the great foreign river and ocean steamers and men-of-war

McCook found herself in a bustling city where, she wrote her mother, “the streets… are no more than lanes, winding about among the houses which seem to have been in many cases set down directly across the natural line of travel… and the narrowness of the lanes is aggravated by the way everyone has of camping out anywhere he pleases to ply his trade.”

The Episcopal mission stations in Wuchang and Hankow consisted of several day and boarding schools for boys and girls (Chinese girls traditionally were not educated), multiple hospitals, and dispensaries along with housing for staff of no more than a dozen missionaries. They, in turn, supported mission outposts in the countryside. McCook began by teaching Chinese boys and studying the language.

The following June, she wrote to her family about the Boxer Rebellion:

China is no doubt in an unsettled condition, but as Bishop Graves wrote in a letter to me … ‘the Yangtse Valley is undoubtedly the safest place in the country’… The society called the Ta Tao Huei (Big Knife Society) or Boxers, has been so long tolerated by the Empress…that it has grown very bold and powerful, and has of late even attacked and (I think) killed a few foreigners. This, you see, is all in Pekin[sic]. As to how far it has spread through China I cannot say, but we have not yet heard of anything serious in this neighborhood.… Remember…that Pekin is halfway across this great empire from us, in a country where communication is very slow with no newspapers to act as fire-feeders and with a population far less homogenous than ours…. Everything goes on just as usual in the Compound—lessons, study, church, exercise— except that we don’t go out so much without escort and I don’t think one of us is frightened. Certainly I’m not…”

Just a week later, however, she moved across the Yangtze to Hankow, having received “news of some signs of uneasiness among a certain section of the people in this neighborhood.” (July 1, 1900). Hankow, a “treaty-port, is always the safest place because of the large foreign-built and guarded concession and Hankow with its foreign volunteers drilling and standing guard, and the English gunboats always on hand, is probably the safest place on the Yangtze,” she wrote to her family. She continued, “When I read, as I did in a ‘Courant’ Bess Morgan sent me…dated May 11, that many missionaries and 100 or so native Christians [Chinese Christians] had been killed in one encounter in China…I groan to think that I can’t afford a daily cablegram. I can only hope you have faith.” She may not have been well informed, however, as she and four other female missionaries soon were sent to Shanghai forsafety. In a letter dated July 5,she wrote, “This morning we learn[ed]that the American Ambassador at Pekin has been killed. Perhaps it is only a rumor. We shall stay in Shanghai [at the Episcopal Mission]… If there is trouble there we might be moved on to Japan.” A postscript read, “tonight start for Japan.”

Rev. Logan Roots, a missionary in Hankow whom McCook would later marry, wrote in a letter to his mother (July 27, 1900):

We are standing face to face with issues of the most far-reaching import. The fact that for the first time in the history of our mission in this region all the country work has been abandoned, and even Wuchang, with its school, hospitals, buildings of all sorts and thousands of dollars worth of property— books and furnishings and personal property—to say nothing of its young native Christians—the fact that all these are now abandoned and left without even a gatekeeper, and turned over to the Chinese officials is only a small indication of the vast change and the troublous times which are ahead of us.”

In all, as many as 180 foreign missionaries and hundreds of Chinese Christians were killed, primarily in the north, before the rebellion was subdued. McCook remained in Japan for three months before moving back to Shanghai. In February 1901 she returned to Hankow, her permanent post, where she was placed in charge of women’s education and reform. It began a period of growth for the mission’s schools as the Chinese realized that they could no longer isolate themselves from Western ways. Of the Chinese women, McCook wrote:

I believe that learning a little will waken them from the stolid, stupid lethargy into which the women fall almost as soon as they are married … It will increase their self respect as well as the respect of their husbands for them, and will, I hope, pave the way as well to unbinding their feet and other desirable reforms.

The following summer, Logan Roots proposed marriage to McCook. Roots was born in Illinois on July 27, 1870 but raised in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Harvard College and the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After being ordained in the American Episcopal Church, he was sent to Hankow in 1896. Before they could be married, McCook had to apply to be released from her contract to serve the church mission as a single woman.

The following summer, Logan Roots proposed marriage to McCook. Roots was born in Illinois on July 27, 1870 but raised in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Harvard College and the Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After being ordained in the American Episcopal Church, he was sent to Hankow in 1896. Before they could be married, McCook had to apply to be released from her contract to serve the church mission as a single woman.

The not-so-young couple (McCook was 32 and Roots 31) married on April 17, 1902 in Hankow. Only their church “family” was present. Two years later, during theirfirst furlough to the United States, the Hartford McCooks finally met Eliza’s new husband and the couple’s infant son John. The Roots would have four more children, all born in China—and all while Logan was away on church business. While in the United States in 1904, Logan was consecrated Bishop of Hankow (one of two bishops overseeing the mission’s two districts in China), a post he would hold for 34 years

Life in China was hectic for the Roots family, revolving around church work and travel, constant hosting duties as leaders of the district church, and the demands of rearing five young children. Eliza homeschooled her children until the three boys were sent to the Kent School in Connecticut, while both daughters would attend the newly created Kuling American School, for which Eliza served as acting principal in 1924.

While she raised her family and fulfilled her duties as the bishop’s wife, Eliza continued to be involved in women’s reform. As noted in a survey she helped develop in 1909 to gain “a more scientific knowledge of conditions which surround us,” issues of concern included cigarette and opium smoking and drinking among Chinese women and girls, gambling, enslavement of young girls, prostitution, “concubinage, or the taking of secondary wives, destruction or abandonment of girl babies,” and foot-binding.

The years leading up to the Revolution of 1911, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of China in 1912, brought political unrest and violence close to home once more. Son John McCook Roots wrote (in Chou: An Informal Biography of China’s Legendary Chou En Lai, Doubleday, 1978) that a bomb stored by revolutionaries exploded just 300 yards from his parents’ home. Much of the revolutionary activity was centered in southern China and finally erupted in Wuchang on October 11, 1911. Hankow was a main battlefield for two months, during which time a large part of the city burned, according to Gray and Sherman. The mission’s St. Paul’s Cathedral became a temporary hospital to treat the wounded. This time, the Roots family did not evacuate. Eliza wrote, “It is certainly one of the most remarkable revolutions of history and we have been at the heart of it.” Both Eliza and Logan were active in relief work, according to Schloss. Logan was chairman of the Famine Relief Executive Committee, and Eliza organized Red Cross work and a sewing workshop for Chinese women to make bedding and clothing for soldiers.

Revolutionary Sun Yat Sen was elected provisional leader of the new Republic of China in December 1911, and Emperor Puyi abdicated the throne two months later. In a letter home dated December 1911, Eliza asked, “What do you think of the election of a reputed Christian [Sun Yat-Sen had been raised in Hawaii, educated in Christian schools, and baptized] … to be the head of a Chinese Republic? Are we dreaming, or is this the same old China that has let a Manchu dynasty egg it on to kill Christians for the last 100 years or more? … But we do believe in the Chinese … & we feel sure that in some way, sometime, they will be able to work out their salvation along the lines of a Republic.” In 1913, Eliza was awarded a medal by General Li, vice president of the new government.

After a period of quiet during World War I, the 1920s saw political conflict between the Kuomintang (KMT), the growing Communist movement, and the government in Peking. In 1925, the “Hankow Incident” caused the Roots family to flee for safety to its country home in Kuling. Eliza wrote her sister of missionaries who had, over the course of a number of weeks, been “chased and stoned, …Some of them are feeling discouraged after years of work… Unfortunately for China, the country is so disunited and the heartless, money-grubbing militarists are so completely in the saddle that even her [China’s] best friends can’t see salvation for her.”

After a visit to the U.S. in 1926 and 1927, Eliza and her youngest daughter Elizabeth tried, against her family’s wishes, to return to China. (The rest of the children remained in school in the U.S.) But fighting centered in Wuchang between the KMT and that group’s former Communist allies kept them in Japan. That violence “probably…[by]members of the communist wing who had been directed to loot and kill foreigners,” she wrote, led to the murder of a personal friend. Logan, who had remained in Hankow, wrote to Eliza in April that he felt the “madness which has beset … the Kuomintang … of late is abating and there may be a reshift soon which will bring some saner elements into power and allow … that you may even come back to Hankow.” By June, mother and daughter had returned. Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-Sen’s successor and leader of the KMT, emerged as the leader of China.

Eliza’s health began to decline in the late 1920s. In the early 1930s, several of her children, having completed their schooling in the United States, came to take up adult careers in China—even as the Communist threat and unrest increased. Her daughter Frances, a graduate of Mount Holyoke College, returned in 1932 to teach in Wuchang. Her son Logan, a physician, returned to Peking to study the language so he could practice medicine there. He was married in Kuling in 1933; Madame Chiang Kai-shek attended. Eliza was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1934 and died in Kuling on August 4, 1934 with her son Logan and daughters Frances and Elizabeth by her side. She was 63. Her husband and sons John and Sheldon arrived a few days later en route from London via a special plane from Shanghai arranged by General and Mme. Chiang Kai-shek.

Logan Roots retired in 1937 and left Hankow with his daughter Frances in 1938 as World War II closed in. Having retired to Mackinac Island, Michigan, he died and was buried there in 1945.

Eliza McCook Roots experienced China during a period of great change as China moved from centuries of dynastic rule through the brief era of the Republic of China to the Communist takeover. The twin Western forces of commercial interest and Christian missionary zeal forced political, economic, and cultural modernization in China, with both positive and negative repercussions. Throughout, Eliza and her family steadfastly continued their work with the conviction that Christianity and education would uplift and empower Eliza McCook, Hankow, China 1902, the most downtrodden of Chinese society.

Eliza McCook Roots experienced China during a period of great change as China moved from centuries of dynastic rule through the brief era of the Republic of China to the Communist takeover. The twin Western forces of commercial interest and Christian missionary zeal forced political, economic, and cultural modernization in China, with both positive and negative repercussions. Throughout, Eliza and her family steadfastly continued their work with the conviction that Christianity and education would uplift and empower Eliza McCook, Hankow, China 1902, the most downtrodden of Chinese society.

Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored and a member of the board of Connecticut Landmarks.

Explore!

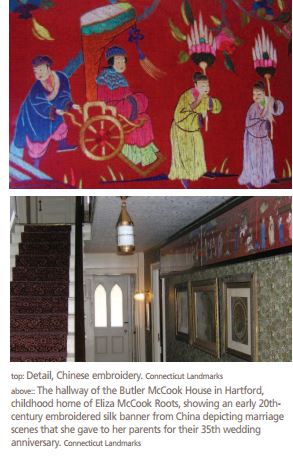

Connecticut Landmarks’s Butler-McCook House & Garden and Main Street History Center, 396 Main Street, Hartford. The home, collections, and garden of four generations of a family dating from the American Revolution to the mid-20th century: a family of physicians, industrialists, missionaries, artists, globe trotters and pioneering educators, and social reformers. For more information visit ctlandmarks.org or call 860-522-1806.

“The Butler-McCook House,” Winter 2003

“Rev. John James McCook: Understanding Homelessness in 1890s Hartford,” Feb/Mar/Apr 2004

“The McCook Boys Collect Baseball Cards,” Fall 2009