By Abraham Ribicoff. Adapted from the original by Ethan Manis

By Abraham Ribicoff. Adapted from the original by Ethan Manis

(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2016

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

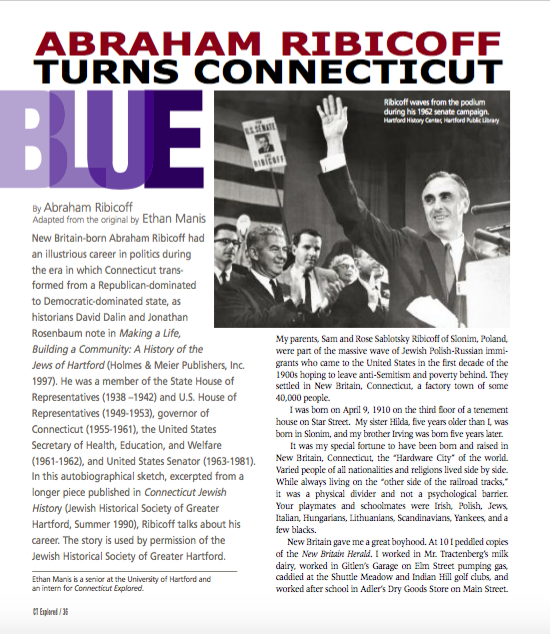

New Britain-born Abraham Ribicoff had an illustrious career in politics during the era in which Connecticut transformed from a Republican-dominated to Democratic-dominated state, as historians David Dalin and Jonathan Rosenbaum note in Making a Life, Building a Community: A History of the Jews of Hartford (Holmes & Meier, 1997). He was a member of the State House of Representatives (1938 – 1942) and U.S. House of Representatives (1949-1953), governor of Connecticut (1955-1961), the United States Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (1961-1962), and United States Senator (1963-1981). In this autobiographical sketch, excerpted from a longer piece published in Connecticut Jewish History (Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford, Summer 1990), Ribicoff talks about his career. The story is used by permission of the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford.

My parents, Sam and Rose Sablotsky Ribicoff of Slonim, Poland, were part of the massive wave of Jewish Polish-Russian immigrants who came to the United States in the first decade of the 1900s hoping to leave anti-Semitism and poverty behind. They settled in New Britain, Connecticut, a factory town of some 40,000 people.

I was born on April 9, 1910 on the third floor of a tenement house on Star Street. My sister Hilda, five years older than I, was born in Slonim, and my brother Irving was born five years later.

It was my special fortune to have been born and raised in New Britain, Connecticut, the “Hardware City” of the world. Varied people of all nationalities and religions lived side by side. While always living on the “other side of the railroad tracks,” it was a physical divider and not a psychological barrier. Your playmates and schoolmates were Irish, Polish, Jews, Italian, Hungarians, Lithuanians, Scandinavians, Yankees, and a few blacks.

New Britain gave me a great boyhood. At 10 I peddled copies of the New Britain Herald. I worked in Mr. Tractenberg’s milk dairy, worked in Gitlen’s Garage on Elm Street pumping gas, caddied at the Shuttle Meadow and Indian Hill golf clubs, and worked after school in Adler’s Dry Goods Stores on Main Street. At 16, in the summer, I had a pick-and-shovel job digging ditches on a new road being laid on Stanley Street. Each job was a learning and maturing process. During the road job, I worked next to Angelo, an Italian immigrant. He saw me suffering from blistered hands and aching back. Until I toughened up he “carried me,” doing my work as well as his. The lesson I learned from him I carried through my entire life to this day: There isn’t a person in the world, no matter how illiterate or simple, who doesn’t know or can do something that I can’t. Every person is deserving of respect. With all these jobs, my parents, unlike many others, never took a dime of my earnings. They insisted that they be deposited in the savings bank to go toward a college education.

Graduating from New Britain High School in February 1927, I was two months shy of 17. I got a job as an expediter at the G.E. Prentice Manufacturing Co. in Kensington. One person who became my close friend was Ed Conlin, an Irish Catholic, who was foreman of the tool room. We went through the election of 1928 together when anti-Catholicism was rampant against the Democratic candidate, Al Smith. At that time I determined to go into politics and help eliminate prejudice of all kinds.

In the fall of 1929 I entered New York University. It was the start of the [Great] Depression. In 1930 I was visited by Fred Troup, vice president of the Prentice Manufacturing Co. He offered me, at the age of 19, the job of being in charge of their sales office in Chicago at the sum of $100 per week. That was then a fortune. I took it with the understanding that I would take some night courses and then would leave to enter law school.

In the fall of 1929 I entered New York University. It was the start of the [Great] Depression. In 1930 I was visited by Fred Troup, vice president of the Prentice Manufacturing Co. He offered me, at the age of 19, the job of being in charge of their sales office in Chicago at the sum of $100 per week. That was then a fortune. I took it with the understanding that I would take some night courses and then would leave to enter law school.

I graduated cum laude [from University of Chicago Law School]in 1933; I was on the law review and a member of the Order of Coif, the honorary society. Having married Rush Siegel in 1932, we returned to Hartford in 1933. I took the bar and became associated with Judge Abraham Bordon. He was my mentor, and after a few years he made me his partner in the firm of Bordon & Ribicoff.

I jumped into politics immediately, starting as a ward heeler [a low-level party member who works to solicit votes]in Hartford’s 12th Ward. On the same floor was another young lawyer—John Bailey. We became close friends. Over corned beef sandwiches from the old Empire Restaurant across from City Hall we talked about what we would do if we controlled the Democratic party.

In 1938 the Democratic party was split. In the Democratic convention to nominate Hartford’s representatives to the Connecticut General Assembly, John Bailey nominated me against the organization nominee, and we won. I still recall [then-party boss] T.J. Spellacy—all six foot six inches—standing up, lifting his hands toward John Bailey, and saying, “John, I give you the party.” John took it and went from town chairman to state chairman to national chairman. I went to the Connecticut legislature and loved it. Beginning in 1938, John and I became a team.

The best place to start in politics is the legislature. Here you met people from all the 169 towns. Like the people in my boyhood, the legislators were a complete mix. All backgrounds of every ethnic strain, every social and economic group, and both parties were represented. I made friends with the overwhelming majority—friendships that lasted my entire life. You learn a basic lesson: You can disagree with a person on an issue or philosophy. Never impugn his character or intent.

From the legislature I went to the judgeship of the Hartford police court. After four years on the bench [I] determined that I was going to practice law and get out of politics.

[The year] 1948 was supposed to be a bad year for the Democrats. John Bailey, who was now state chairman, wanted to elect Chester Bowles for governor on the Democratic ticket and importuned me to take the nomination for Congress from the 1st Congressional District. After saying, “No, no,” I succumbed to my love of politics, was nominated, and won.

On July 28, 1952 United States Senator Brien McMahon died. I was designated to run [to fill]his unexpired term. Never having run statewide, having a short time to mount a full campaign, and in the shadow of [Republican candidate Dwight D.] Eisenhower against [Democratic candidate Adlai] Stevenson, I had a tough road against Prescott Bush [father of President George H. W. Bush], the G.O.P. nominee. I lost, but ran more than 100,000 votes ahead of [the rest of]the Democratic ticket.

In 1954 the race for governor came along. Because of my run in 1952 and my record, I received the nomination for governor. This was the first and only campaign where anti-Semitism raised its head. John Davis Lodge was the Republican governor. We were friends, having served together in congress. [Ed.: Lodge was not the source of the anti-Semitism.] This disturbed me, and I started to appeal to the sense of fairness of the voter of Connecticut.

On the Friday before the election both Governor Lodge and I were to appear for one half hour at the only television station in Connecticut: Channel 8 New Haven. When it was my turn to go on, I threw away my script, went before the television camera, and winged it. I just said what was in my heart: As a child I had grown up in New Britain, and I had had this American dream that in this great country of ours, anybody could achieve any office he sought or any position in private or public life, irrespective of race, color, creed, or religion. A person was to be accepted for what he was—his character, his ability, his integrity—and I assumed that this is what the State of Connecticut really was and what Connecticut really meant.

I won the [gubernatorial]election by 3,200 votes. The speech made the difference. I was the only Democrat that won. From lieutenant governor down it was Republican. More important, not since has there ever been raised in any Connecticut election a candidate’s religion, race, color, creed or ethnic origin.

I was isolated as a lone Democrat at the [State] Capitol. The House of Representatives was Republican, and the Senate was tied. I chose for my inaugural day address the theme “The Integrity of Compromise.” To govern I realized that confrontation would not work. A bipartisan approach was needed. My years in the state legislature paid off.

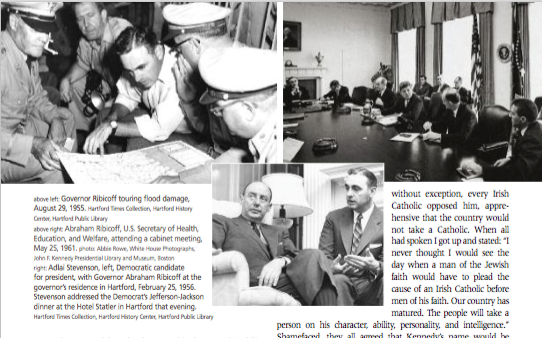

In 1956 John Bailey and I led the drive to get the vice presidential nomination for U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy. To stimulate interest in the Democratic cause, Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson [running against President Dwight Eisenhower]decided to open up the Democratic convention for the vice presidential spot. [Party leaders met] behind closed doors at the Chicago Stockyards Inn. Most of the people in that room were Irish Catholics. When Kennedy’s name came up, without exception, every Irish Catholic opposed him, apprehensive that the country would not take a Catholic. When all had spoken I got up and stated: “I never thought I would see the day when a man of the Jewish faith would have to plead the cause of an Irish Catholic before men of his faith. Our country has matured. The people will take a person on his character, ability, personality, and intelligence.” Shamefaced, they all agreed that Kennedy’s name would be presented to the convention.

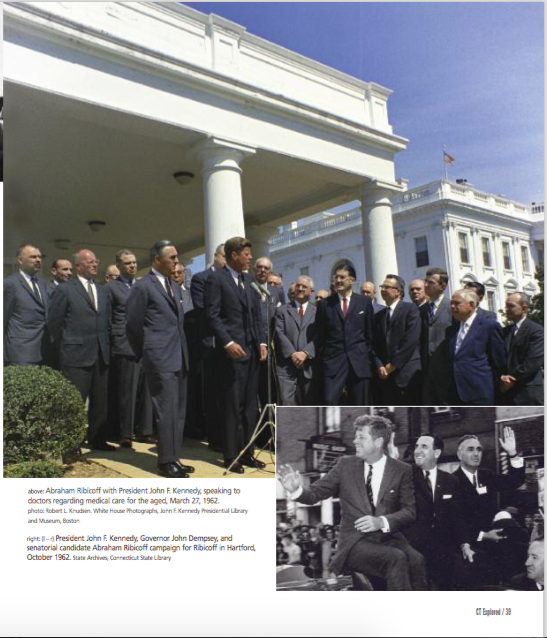

I nominated Kennedy, and he lost by a handful of votes. That was the best break he got—Stevenson’s loss could not be blamed on a Catholic vice presidential candidate. [Kennedy] campaigned up and down the nation, and his popularity soared. John Bailey and I then joined John Kennedy in planning for the presidential nomination in 1960. In 1958 I was re-elected [governor]. I carried with me the entire Democratic state ticket, a United States Senator, six Congressmen, and a Democratic legislature—the first time in 86 years.

Between 1958 and 1960 John Bailey and I devoted a great deal of our energies toward the nomination and election of John Kennedy to the presidency of the United States. [After he won] President Kennedy designated me as Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare in his cabinet. I missed elective politics and in 1962 decided to run for the United States Senate. I was elected and re-elected in 1968 and 1974. In 1972 I married Lois Mell Mathes. [Ed.: Ribicoff’s first wife died earlier that year.]

Between 1958 and 1960 John Bailey and I devoted a great deal of our energies toward the nomination and election of John Kennedy to the presidency of the United States. [After he won] President Kennedy designated me as Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare in his cabinet. I missed elective politics and in 1962 decided to run for the United States Senate. I was elected and re-elected in 1968 and 1974. In 1972 I married Lois Mell Mathes. [Ed.: Ribicoff’s first wife died earlier that year.]

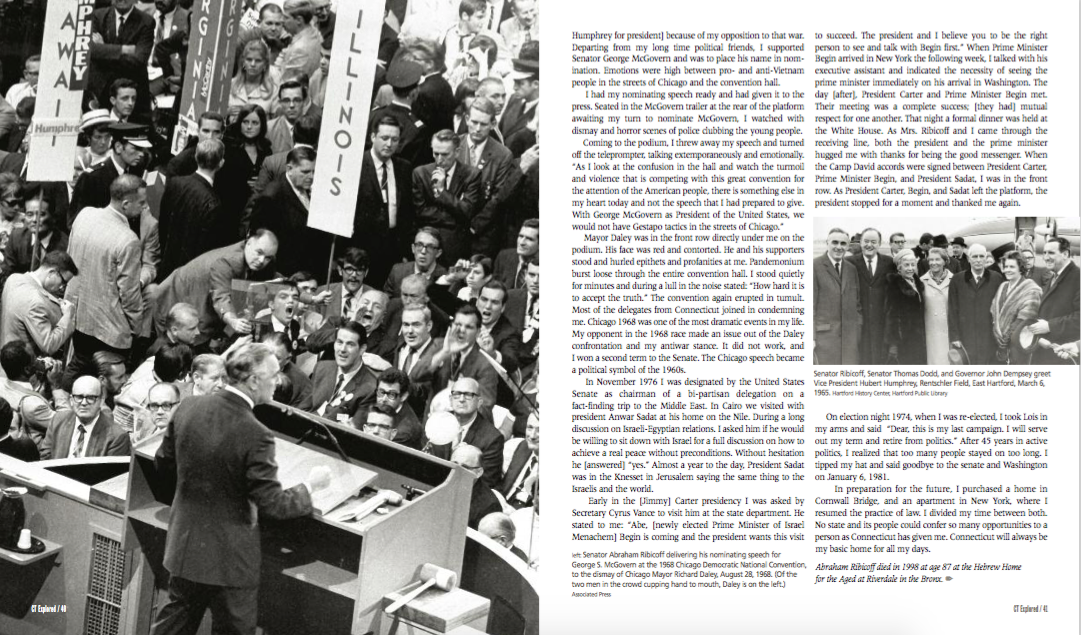

[The year] 1968 was a tumultuous year in our nation. The people were deeply and passionately divided over the Vietnam War. Personally, I could not support [Vice President Hubert Humphrey for president] because of my opposition to that war. Departing from my long time political friends, I supported Senator George McGovern and was to place his name in nomination. Emotions were high between pro- and anti-Vietnam people in the streets of Chicago and the convention hall.

I had my nominating speech ready and had given it to the press. Seated in the McGovern trailer at the rear of the platform awaiting my turn to nominate McGovern, I watched with dismay and horror scenes of police clubbing the young people.

Coming to the podium, I threw away my speech and turned off the teleprompter, talking extemporaneously and emotionally. “As I look at the confusion in the hall and watch the turmoil and violence that is competing with this great convention for the attention of the American people, there is something else in my heart today and not the speech that I had prepared to give. With George McGovern as President of the United States, we would not have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago.”

Coming to the podium, I threw away my speech and turned off the teleprompter, talking extemporaneously and emotionally. “As I look at the confusion in the hall and watch the turmoil and violence that is competing with this great convention for the attention of the American people, there is something else in my heart today and not the speech that I had prepared to give. With George McGovern as President of the United States, we would not have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago.”

Mayor Daley was in the front row directly under me on the podium. His face was red and contorted. He and his supporters stood and hurled epithets and profanities at me. Pandemonium burst loose through the entire convention hall. I stood quietly for minutes and during a lull in the noise stated: “How hard it is to accept the truth.” The convention again erupted in tumult. Most of the delegate from Connecticut joined in condemning me. Chicago 1968 was one of the most dramatic events in my life.

My opponent in the 1968 race made an issue out of the Daley confrontation and my antiwar stance. It did not work, and I won a second term to the Senate. The Chicago speech became a political symbol of the 1960s.

In November 1976 I was designated by the United States Senate as chairman of a bi-partisan delegation on a fact-finding trip to the Middle East. In Cairo we visited with president Anwar Sadat at his home on the Nile. During a long discussion on Israeli-Egyptian relations. I asked him if he would be willing to sit down with Israel for a full discussion on how to achieve a real peace without preconditions. Without hesitation he [answered]“yes.” Almost a year to the day, President Sadat was in the Knesset in Jerusalem saying the same thing to the Israelis and the world.

Early in the [Jimmy] Carter presidency I was asked by Secretary Cyrus Vance to visit him at the state department. He stated to me: “Abe, [newly elected Prime Minister of Israel Menachem]Begin is coming and the president wants this visit to succeed. The president and I believe you to be the right person to see and talk with Begin first.” When Prime Minister Begin arrived in New York the following week, I talked with his executive assistant and indicated the necessity of seeing the prime minister immediately on his arrival in Washington. The day [after], President Carter and Prime Minister Begin met. Their meeting was a complete success; [they had]mutual respect for one another. That night a formal dinner was held at the White House. As Mrs. Ribicoff and I came through the receiving line, both the president and the prime minister hugged me with thanks for being the good messenger. When the Camp David accords were signed between President Carter, Prime Minister Begin, and President Sadat, I was in the front row. As President Carter, Begin, and Sadat left the platform, the president stopped for a moment and thanked me again.

On election night 1974, when I was re-elected, I took Lois in my arms and said “Dear, this is my last campaign. I will serve out my term and retire from politics.” After 45 years in active politics, I realized that too many people stayed on term too long. I tipped my hat and said goodbye to the senate and Washington on January 6, 1981.

In preparation for the future, I purchased a home in Cornwall Bridge, and an apartment in New York, where I resumed the practice of law. I divided my time between both. No state and its people could confer so many opportunities to a person as Connecticut has given me. Connecticut will always be my basic home for all my days.

Abraham Ribicoff died in 1998 at age 87 at the Hebrew Home for the Aged at Riverdale in the Bronx.

Ethan Manis graduated from the University of Hartford in May 2016 and was an intern for Connecticut Explored.

Read more stories from the Spring 2016 issue.