By Paula Brisco

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

By the time landscape architect Beatrix Farrand (1872–1957) retired, her legacy included the grounds of Dumbarton Oaks (once a private estate, now a museum) in Washington, D.C., gardens for the Morgan Library in New York City, the New York Botanical Garden, and the White House, and work on college campuses including Yale and Princeton University. For a time she was forgotten, and many of her gardens disappeared. But in the 1980s historians brought Farrand back into the spotlight.

In the years around 1920, Farrand created three gardens that, as luck would have it, are the only surviving examples of her private gardens in Connecticut. Since her rediscovery, these remarkable gardens, initially designed for private estates, have been restored for the enjoyment of the public: Harkness Memorial State Park in Waterford, Hill-Stead Museum in Farmington, and Three Rivers Farm in Bridgewater.

Farrand was not in fact new to Connecticut or to landscape design in 1920: the only female founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, she had established her practice in 1896, and by 1918 she had designed gardens in Greenwich, Darien, and New Haven and planting plans for the Westover School in Middlebury (designed by architect Theodate Pope Riddle of Hill-Stead).

She was born Beatrix Jones and grew up in a life of some privilege (an apartment in New York City, summers spent on Mount Desert Island in Maine, the grand tour of Europe); nonetheless, as a woman, not all doors were open to her. She did not attend college but gained her horticultural education in 1893 through hands-on training with Charles Sprague Sargent, founder and director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum, and by training her eye through travel abroad. She had the means and introductions to meet landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and, in Britain, the renowned designers Gertrude Jekyll and William Robinson.

Beatrix initially secured commissions through her social connections—and they were very good connections. Her father’s sister was the novelist Edith Wharton; novelist Henry James was a close friend of the family; and Max Farrand, whom she married in 1913, was chairman of the history department at Yale. Before long Beatrix Farrand had made a name for herself, particularly in the Northeast, and her strong work spoke for itself.

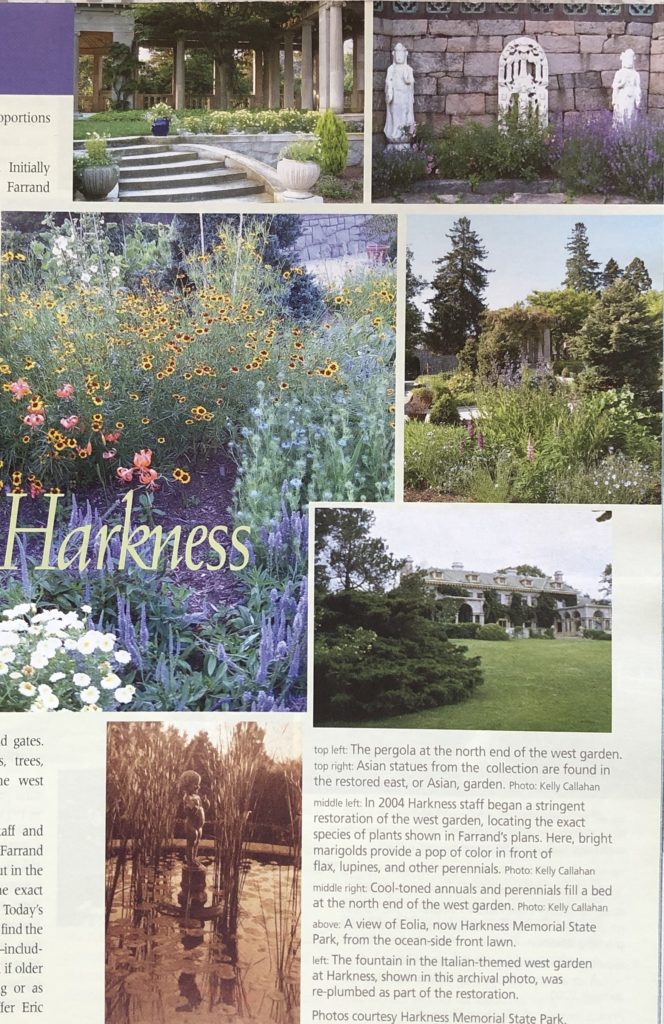

Eolia on the Sea

Through Max Farrand, Beatrix met his Yale friend Edward Harkness, which led to a commission for a garden design at Eolia, Harkness’s summer estate in what is now Waterford. Today the estate is known as Harkness Memorial State Park, and the garden there is perhaps the most extensive Farrand garden in Connecticut.

Through Max Farrand, Beatrix met his Yale friend Edward Harkness, which led to a commission for a garden design at Eolia, Harkness’s summer estate in what is now Waterford. Today the estate is known as Harkness Memorial State Park, and the garden there is perhaps the most extensive Farrand garden in Connecticut.

Edward S. Harkness inherited a fortune that his father had earned through substantial investments in John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. The younger Harkness and his wife, Mary, became ardent philanthropists, giving more than $200 million to nonprofit organizations, including nearby Connecticut College and Yale University. The Harknesses owned several properties, but Eolia was one of their favorites. The Roman Renaissance and classical revival–style villa was built in the early 1900s by architects Lord, Hull & Hewlett and purchased by the Harknesses in 1907. The grandly sited, U-shaped mansion faces south to a view of Long Island Sound.

Sometime around 1918 the Harknesses approached Farrand for a new planting plan to work within the existing space of Eolia’s west garden (also known as the Italian garden). They wanted something that would combine Farrand’s innovative use of plant materials and textures with Mary Harkness’s color preferences. Farrand’s design reflects her study of the work of English garden designer Gertrude Jekyll. Mac Griswold and Eleanor Weller, writing in The Golden Age of American Gardens, eloquently describe the impact of the Harkness planting:

Around the cypresses, which were the focal points of the three main beds, swirled drifts of blues in expanding, loosely circular patterns: grayish-blue catnip, Nepeta mussinii, soft blue Salvia patens, nigellas, including one named ‘Miss Jekyll’, veronicas, campanulas, and many others…. However, the garden was no fluffy pastel vision. Farrand … did not omit the dark, warm colors that spiked English borders with drama. Here, used sparingly, were orange Lilium elegans, French marigolds named ‘Mahogany’, dahlia ‘Black Knight’, and maroon nasturtiums.[i]

Farrand continued work at Eolia until 1929. She replaced a lawn tennis court with a walled east garden (the Asian garden), added a boxwood parterre, and installed a wild-looking alpine rockery with winding paths, stream, and tiny pond. The rockery not only connected the parterre to the south entrance of the formal west garden but also linked the entire garden with the grassy swells and rocky ocean shoreline—masterfully joining the house and gardens with nature beyond.

In 1950 Mary Harkness willed Eolia to the state for Connecticut citizens to enjoy. Over subsequent decades the garden, its structures, and the house began to suffer from age and the effects of oceanfront weather. In the late 1980s a hurricane damaged part of Eolia’s roof, and the mansion was closed to visitors. Shrubs outgrew their spots, and the garden’s proportions were lost.

In stepped the Friends of Harkness. Initially an informal group of Harkness and Farrand enthusiasts, Friends of Harkness Memorial State Park was incorporated in 1992 with the goal of helping to restore and preserve the park, explains Chris Callahan, president of the Friends. Following Farrand’s original plans archived at the University of California’s Department of Landscape Architecture at Berkeley, the Friends raised $25,000 to restore the east garden in 1994 and 1995. The replanted, historic garden created a buzz and signaled a new life stage for the park.

From 1996 to 1998 the state undertook an ambitious restoration of the mansion and the rest of the gardens. The goal was to bring Eolia back to its early 1930s glory. In the gardens, restoration meant first addressing the hardscape: installing new irrigation systems, regrading paths and replacing curbing, repairing stone walls and fountains, restoring the tea room and garden pergola, and restoring or replacing the wrought-iron fencing and gates. Finally, in 1998, replanting of shrubs, trees, perennials, and annuals began in the west garden and the rock garden.

It was a good start. In 2004 park staff and volunteers began a further review of the Farrand plan and discovered that many plants put in the gardens were modern cultivars, not the exact species or varieties specified by Farrand. Today’s goal is to replicate the gardens exactly, to find the correct plants to create the correct look—including bloom time, color, and height—even if older varieties of plants don’t bloom as long or as heavily as modern varieties. Park staffer Eric Hansen has made it his personal quest to track down every historic plant; to date he has located about 90 percent of them from sources in the United States, Canada, France, and South Africa, says Eileen Grant, past president of Friends of Harkness and chair of the group’s horticultural committee.

Of all the gardens at Harkness, Farrand’s favorite was the rockery, notes Grant, with its spring-flowering bulbs, irises, creeping phlox, ferns, cotoneasters, pines, and rhododendrons planted amid the rocks. This has been the most difficult garden to re-create because there is no planting plan, but there are plenty of historic photographs. The rockery will soon see another round of restoration. “It looks good now,” says Grant, “but we know it’s not right.” It will be.

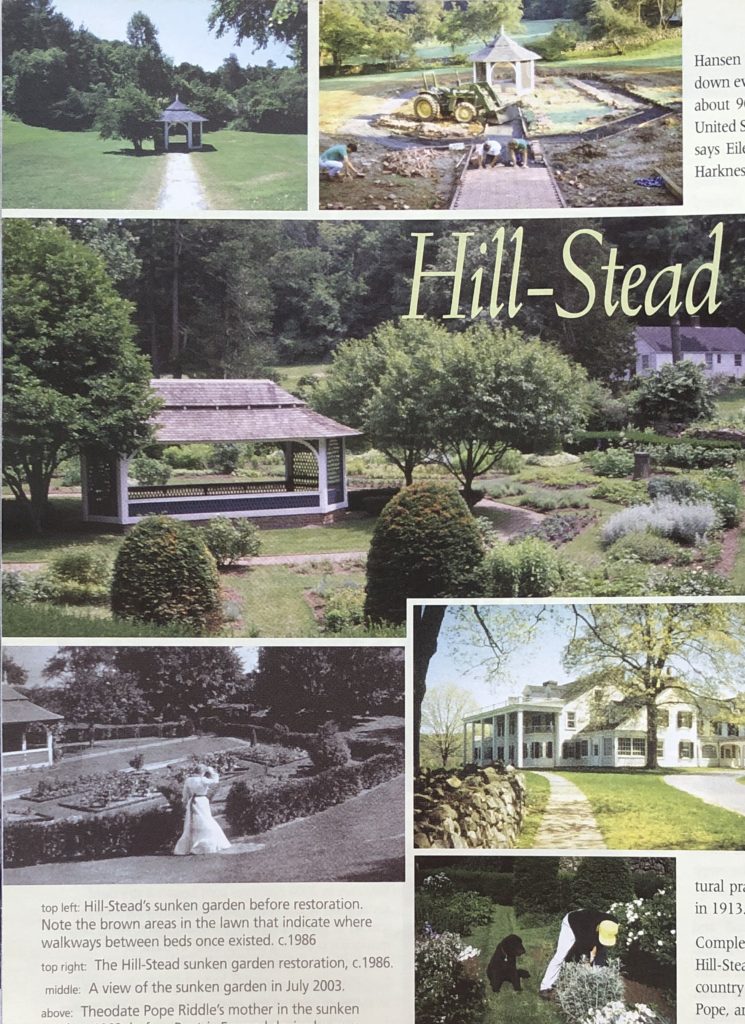

Two Pioneering Women Collaborate

About the time that Farrand began work at Harkness, she received a commission from Theodate Pope Riddle (1867–1946) for her garden at Hill-Stead in Farmington. Like Farrand, Riddle was born into privilege, and she carved for herself a professional niche in a field dominated by men. As Miss Pope she designed the Hill-Stead mansion in close collaboration with the New York architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White. She opened her own architectural practice in 1905 and her New York office in 1913.

About the time that Farrand began work at Harkness, she received a commission from Theodate Pope Riddle (1867–1946) for her garden at Hill-Stead in Farmington. Like Farrand, Riddle was born into privilege, and she carved for herself a professional niche in a field dominated by men. As Miss Pope she designed the Hill-Stead mansion in close collaboration with the New York architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White. She opened her own architectural practice in 1905 and her New York office in 1913.

Completed in 1901, the colonial revival Hill-Stead served as a retirement home and country estate for her parents, Alfred and Ada Pope, and as a showcase for the family’s collection of French impressionist paintings, furnishings, and decorative arts. Landscape designer Warren Manning, a protégé of Frederick Law Olmsted, assisted Theodate and her parents with the overall landscape conception, which included miles of stone walls, transplanted mature trees, a walking garden, a sunken garden, and a working dairy farm and orchard. After her marriage in 1916, Theodate and her husband, John Riddle, continued to live at Hill-Stead.

When the recently married Riddle wanted a redesign of Hill-Stead’s existing sunken garden, it was natural for her to turn to Farrand. Farrand and Riddle had been introduced by novelist and mutual acquaintance Henry James as early as 1904,[ii] and the two women collaborated on the plans for the Westover School in Middlebury—Riddle designing the buildings beginning in 1906 and Farrand the landscape in 1912. Farrand’s skill in combining formal and naturalistic garden elements dovetailed with Riddle’s vision of the Hill-Stead landscape, in which gardens, lawns, and meadows flowed into one another and around the elegant structure of the main house and its barns and outbuildings.

Hill-Stead’s sunken garden was created at the same time as the house. The garden fits into a natural depression contained by walls of dry-laid native stone. Within the depression is the octagonal garden of 36 flowerbeds framed by a low hedge. A central axis leads from the steps near the house into the garden, along a box-lined brick walk through the summerhouse, and out past a stone sundial to the meadow gate. Brick and grass walkways lead around the flowerbeds. Farrand’s challenge was to work within this garden framework and to develop a plan to transform its formal plantings into something structured yet informal.

And transform it she did. The beds start as low swirls of verbena, heliotrope, and lavender around the summerhouse. The plants increase in height and drama as the beds radiate outward, concluding with five-foot-tall stands of rue, giant Solomon’s seal, and lilies that embrace the garden and echo the slope of the dell. Visitors are greeted by drifts of blooms in blue, pink, salmon, cream, and white and by varied-texture foliage in grays and greens—the very washes of color and texture for which Farrand is renowned. It is said that Farrand chose the colors of the plants from the French impressionist paintings in the house, yet she also specified surprising hits of color that punctuate the pastels: “Brown” primroses form a carpet under the pink-flecked York and Lancaster rose. Black and white Sweet William shoulders up to delicate Gillenia trifoliata. Buttery Gladiolus primulinus rises up through the finely cut leaves of white perennial geranium.

Unfortunately, no photos of this garden have been found, says Hill-Stead curator Cindy Cormier, and research is still under way to determine how much of Farrand’s plan was executed. In the early 1940s, during wartime shortages, the sunken garden was seeded over, Cormier notes. When Riddle died in 1946, her will established Hill-Stead as a museum, but the garden disappeared.

Forty years later volunteers from the Connecticut Valley Garden Club and the Garden Club of Hartford, with the assistance of landscape architect Shavaun Towers, undertook reclamation of the one-acre plot. During the process they located Farrand’s original plans, labeled “planting plan, garden of Mrs. J. W. Riddle, Farmington, Conn.” at the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of California at Berkeley. This plan is the basis for the garden that visitors see today.

As at Harkness, Hill-Stead staff and volunteers are taking advantage of the increased interest in and access to historic plants to locate more appropriate cultivars for the sunken garden—such as the long-missing brown primrose. Sometimes Mother Nature deals cruel blows: Hill-Stead’s delphiniums have been done in by microscopic cyclamen mites, so with the blessing of Farrand expert Patrick Chaussé, curator Cindy Cormier has elected to replace the failing delphinium with varieties of salvia that were part of Farrand’s plant palette in other gardens of the same period.

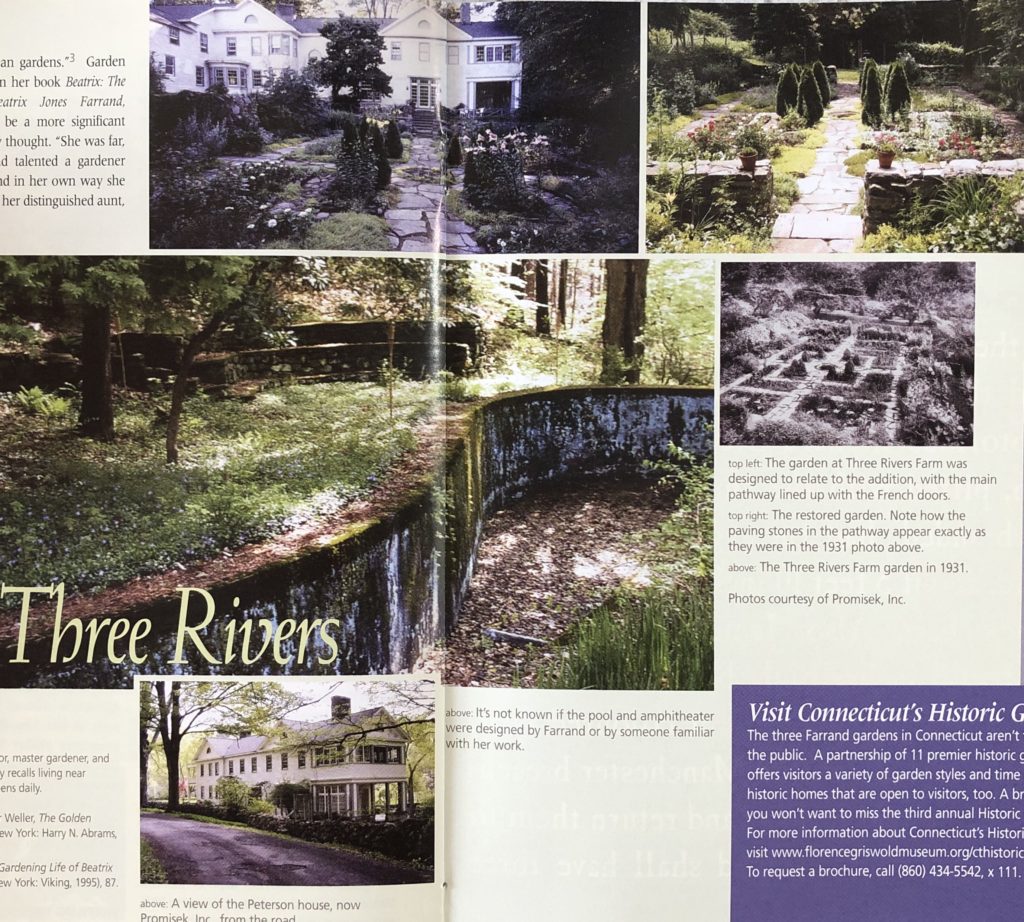

Shepaug Rediscovered

The Farrand garden on the property of Promisek Incorporated in Bridgewater is a story of a hidden garden rediscovered, the result of sleuthing on the part of Roxbury resident and garden historian Pamela Edwards in 1991. Edwards noticed in a list of Farrand’s commissions a plan for “Dr. Frederick Peterson, Three Rivers Farm, Shepaug, Connecticut.” But where was this Shepaug? Referring to a turn-of-the-20th-century railroad map, Edwards found a whistle-stop called Shepaug not far from the confluence of the Housatonic, Shepaug, and Pond Brook rivers. She located on a modern-day map a long, remote road leading through Bridgewater down to the Housatonic River. Heading out in her car, Edwards reached the house once owned by Peterson and recognized the nuances of Farrand’s style in a granite seat in the roadside garden wall. Sure enough, behind the house was a stone-wall-enclosed garden complete with flagstone pathways, remnants of the Farrand garden. The house and property now belonged to the nonprofit Promisek Incorporated, a Catholic educational and environmental association. With Promisek members’ enthusiastic support, Edwards contacted the University of California at Berkeley and got copies of the nine Peterson plans in the Farrand archives.

The Farrand garden on the property of Promisek Incorporated in Bridgewater is a story of a hidden garden rediscovered, the result of sleuthing on the part of Roxbury resident and garden historian Pamela Edwards in 1991. Edwards noticed in a list of Farrand’s commissions a plan for “Dr. Frederick Peterson, Three Rivers Farm, Shepaug, Connecticut.” But where was this Shepaug? Referring to a turn-of-the-20th-century railroad map, Edwards found a whistle-stop called Shepaug not far from the confluence of the Housatonic, Shepaug, and Pond Brook rivers. She located on a modern-day map a long, remote road leading through Bridgewater down to the Housatonic River. Heading out in her car, Edwards reached the house once owned by Peterson and recognized the nuances of Farrand’s style in a granite seat in the roadside garden wall. Sure enough, behind the house was a stone-wall-enclosed garden complete with flagstone pathways, remnants of the Farrand garden. The house and property now belonged to the nonprofit Promisek Incorporated, a Catholic educational and environmental association. With Promisek members’ enthusiastic support, Edwards contacted the University of California at Berkeley and got copies of the nine Peterson plans in the Farrand archives.

Farrand designed the garden in 1921 for Dr. Frederick Peterson, a noted New York neurologist who entertained family, friends, and clients on his 300-acre property, which he named Three Rivers Farm. Farrand knew Peterson from an earlier commission, a 1909 town garden she designed for him on West Fiftieth Street in New York City. Peterson was a front-runner in his field, notes Kristin Havill, garden curator at Promisek. He had a thriving practice, and he advocated for reforming so-called lunacy asylums, asserting that the land was a good healing tool for mentally ill people. He was a plant enthusiast who created an arboretum of sorts at Three Rivers Farm.

The Three Rivers Farm garden was meant to be viewed from an addition to the main house, although Farrand designed the garden before the addition was built, says Havill. A central path leads from French doors straight out through the enclosed, walled garden; other paved paths lead visitors around the beds. An early photograph shows the young garden planted with Farrand’s signature evergreen “bullets”—upright yews, junipers, or spruces at the corners of paths—and the central flagstone path exactly as it appears today. The beds along the stone-walled perimeter contain perennials in pink, purple, white, and blue, with a few surprises like a maroon dahlia. The inside beds feature roses in pinks and reds edged with a lacy fringe of fragrant annuals.

By the time Promisek acquired the property in 1978, the walled garden had been overtaken by decades of overgrowth, but the hardscaping remained. Almost like archeologists, Promisek members cleared the brush to reveal flagstone pathways and the handsome stone walls around the garden. When restoration began in 1991, some of the smaller paths were missing, recalls Pamela Edwards. Volunteers were fortunate to find most of the beds’ coping stones buried a few inches deep in the soil.

Today Havill and her team of volunteers maintain the garden. It has been a challenge to stick with the historic plants, in large part because nearby trees have matured, casting more shade on the garden than many plants in Farrand’s design can tolerate. Deer and voles have also posed problems. Havill uses the listed plants as long as they are healthy. If not, she strives for the essence of the design. “We try to keep as much integrity as we can given the challenges and parameters,” she says.

These three Farrand gardens illustrate three different approaches to restoring them, but one common passion for the designs of the woman many have called “the American Gertrude Jekyll,” referring to the legendary English garden designer, plantswoman, and writer (who designed a garden in 1926 for the Glebe House in Woodbury). Garden historians are quick to point out, however, that Farrand was not a derivative designer. “For all its Jekyllesque plantings, ‘Eolia’ was not an English garden,” Griswold and Weller write. “Farrand planted American natives in a way perhaps only possible for a sophisticated American who had seen many European gardens.”[iii] Garden historian Jane Brown, in her book Beatrix: The Gardening Life of Beatrix Farrand, pronounces Farrand to be a more significant designer than previously thought. “She was far, far more perceptive and talented a gardener than Gertrude Jekyll, and in her own way she achieved as much as did her distinguished aunt, Edith Wharton.”[iv]

Wherever Beatrix Farrand stands in the history of landscape design, it’s clear that she left a strong visual legacy. Her magical combinations of plant colors and textures, and her ability to blend formal with the informal, the native plant with the cultivar, and the human-scaled garden with the wilder landscape beyond, can all be seen in the gardens of Harkness, Hill-Stead, and Promisek. We in Connecticut are fortunate to have three of her works so close at hand.

EXPLORE!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s historic landscape on our TOPICS page.

Read more about Hill-Stead Museum

Read about Frederick Law Olmsted in Connecticut

Read about Connecticut’s Historic Rose Gardens

Harkness Memorial State Park, 275 Great Neck Road, Waterford; (860) 443-5725; www.ct.gov/dep. Open daily 8 a.m. to sunset. Mansion tours: 10 a.m. to 2:15 p.m. Saturday, Sunday, and holidays from Memorial Day weekend until Labor Day. For information about volunteering at Harkness, visit www.harkness.org and click on the link to Friends of Harkness; the Friends meet Wednesday from April till frost.

Hill-Stead Museum, 35 Mountain Road, Farmington; (860) 677-4787; www.hillstead.org. Grounds open daily 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. free of charge. House tours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Tuesday through Sunday from May through October; 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday from November through April. Garden volunteers meet Wednesday from May through September; call or visit the Web site for details.

Promisek Incorporated’s Beatrix Farrand Garden at Three Rivers Farm, 694 Skyline Ridge Road, Bridgewater; (860) 354-1788; www.promisek.org. Open to the public the last Sunday of each month May through September, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and during the Garden Conservancy’s annual Garden Open Days. Volunteers work in the garden one day a month; call or e-mail (through the Web site) for more information.

Paula Brisco, a freelance editor, master gardener, and volunteer at Hill-Stead, fondly recalls living near Harkness and visiting

Footnotes

[i] Mac Griswold and Eleanor Weller, The Golden Age of American Gardens (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), 67.

[ii] Jane Brown, Beatrix: The Gardening Life of Beatrix Jones Farrand, 1872–1959 (New York: Viking, 1995), 87.

[iii] Griswold and Weller, Golden Age, 67.

[iv] Brown, Beatrix, 201.