By Michelle Wong

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This issue’s Shoebox Archive is adapted from an independent study project written by Michelle Wong, a student at The Gunnery, a coeducational college preparatory boarding and day school for 9th-12th-grade students in Washington, Connecticut, during the winter term 2003/2004 of her senior year.

I followed my sister’s footsteps to continue my studies in America. In the 21st century, there are numerous Chinese and Hong Kong students attending secondary and tertiary schools abroad. Families and funding organizations believe that after the return of the overseas students, they will contribute to their motherland with their learning. This thinking even dates back to the end of the 19th century. China, during the Ching Dynasty, believed that, by sending outstanding young boys to receive an education in America, Chinese power would be strengthened militarily, technologically, and economically. However, the corrupted Chinese government did not put all of the 120 American-educated young men to good use after their return. Only a minority are still being honored for their contributions. Because of a sudden call from the Chinese government in 1881, they had to curtail their studies. Their great expectations vanished. Respect was now replaced by contempt and disgust.

I want to express gratitude and respect for the residents of Washington, Connecticut, where two young Chinese boys, Lok Wing Chuan and Tsai Cum Chiong, got to know Mrs. Julia Leavitt Richards, who helped them grow up and develop to become courteous and courageous in a warm and encouraging environment. Also, the Chinese should be proud of the boys as they were good representatives with morality and integrity. Their stories are like a bridge bringing the Americans and the Chinese together.

I can imagine how hard it was for two 14-year-old Chinese boys to study English in America in 1872. Even a 14-year-old Chinese girl who came to study in America 128 years later still has to face hardships and difficulties. What is their story? It began with a fine man, Yung Wing.

In early 1839, Rev. Samuel Robbins Brown, a Yale-educated American missionary from East Windsor, Connecticut, came to Macau, China. He established a school. When his health turned worse in 1847, he returned to America with three students. Yung Wing volunteered. In 1854, Yung Wing graduated from Yale College (now Yale University). He was the first Chinese graduate to take a degree from an American college. He believed that if others could gain knowledge of technology, science, military affairs, and Western culture, they could put their new knowledge and skills to good use to turn China into a developing country. After many years of effort and disappointment, Wing obtained government approval. Yung Wing’s Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) called for the government to select 120 young boys ranging in ages from 12 to 15 to be sent to America in groups of 30 each year. The education for each student was designed to last 15 years.

Yung Wing wrote a letter to Noah Porter, President of Yale College, to explain the Ching government’s plan. He emphasized that the CEM was government funded, so the boys were not to be allowed to withdraw from their studies, take American citizenship, or work for their own benefit. In 1872, the first detachment of students left for America.

Yung Wing established the headquarters of the CEM in Hartford. Several boys were placed there to learn English and Western manners before they attended school. The other boys were placed to live with American host families in small towns and study in schools scattered throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts. They were expected to continue their Chinese lessons and dress and behave like a Chinese. Their language and customs were reinforced by frequent visits to the headquarters in Hartford.

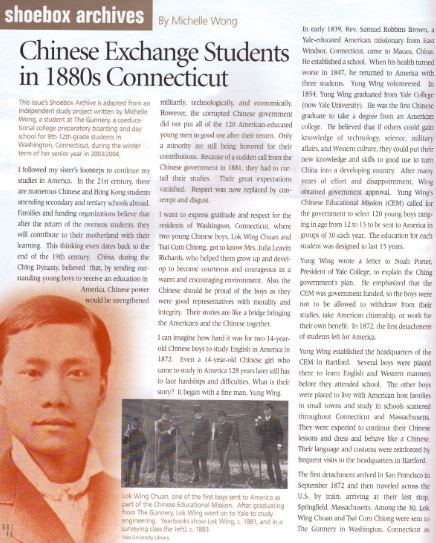

The first detachment arrived in San Francisco in September 1872 and then traveled across the U.S. by train, arriving at their last stop, Springfield, Massachusetts. Among the 30, Lok Wing Chuan and Tsai Cum Chiong were sent to The Gunnery in Washington, Connecticut as day students. Normally, boys were placed with the families of doctors and ministers; however, because Rev. Willis Colton was unable to take the boys, Julia Leavitt Richards, a widow of a doctor, took them into her home.

I was not able to discover enough information about Tsai Cum Chiong, but Lok Wing Chuan led an exciting yet tragic life. Lok Wing was born in Canton, China on August 16, 1860, but he was listed as a 14-year-old boy when he arrived in America. Arriving without understanding or speaking English, the two boys were brave to be in the situation they were in. They were welcomed and made friends quickly. After the first few days, they started to play with the other town kids. They became fast friends with George Colton, the minister’s son, who noted in an article about his childhood friendship with Lok Wing that the Chinese boys “were exceedingly good at sports and no whit behind the rest of the world in boydom.”

In a speech during an alumni dinner in 1908, Lok Wing recalled his studies at The Gunnery:

Being armed only with a knowledge of the alphabet, without a corresponding knowledge of its eccentric and arbitrary combinations…I was placed under the maternal care of Mrs. Richards. Under her instruction for a couple of years, I became identified with the Gunnery institution in the department of oratory under Mr. Gunn, in the department of mathematics and Latin under Mr. Brinsmade. At the outset I got on in Latin admirable and charmingly well till I came to the third book of Caesar, where this ancient warrior gave a graphic but knotty description of the bridge; then I wondered why my Government sent me here to study a dead language…However, I continued my Latin until I was well qualified …to pass successfully my entrance examination at Yale, as the boys say, ‘without a flunk.’ Neither will I forget that moment of ecstasy at the blackboard when…I successfully demonstrated that the sum of the square of the base and perpendicular of a right-angle triangle equaled the square of the hypothenuse [sic]. Then I thought I had the mathematical genius of Euclid, till later on in college, when I was confronted with the sublime theories of calculus; then I again wondered why my Government sent me here to try to solve the unknowable.”

After eight years at The Gunnery, Lok Wing graduated and prepared for college at the Norwich Free Academy. He then entered Sheffield Scientific, the scientific college that later merged with Yale College to form Yale University at Yale College. At the beginning of his junior year in 1881, however, all the CEM students were ordered by the Ching government to return to China. It is not clear exactly how or exactly when Lok Wing returned to the United States. One source records him as returning to China in August, where he was assigned to the Foochow Naval School. His boyhood friend George Colton tells, however, of his “escape by jumping overboard from the prison ship in the harbor of Hong Kong and swimming to a British war vessel which carried him back to Honolulu, from where he got into communication with Mrs. Richards.” We do know that he returned to Yale and graduated from the Civil Engineering course in 1883. After finishing, he followed the profession of Civil Engineering for a year before the Chinese government appointed him to serve as their Vice-Consul in New York. At last, the Chinese government recognized him as a useful and loyal man.

On June 22, 1890, he married an American named Margaret. They had no children. While living in New York, they visited Washington frequently.

In 1909, Lok Wing told Colton about some threatening letters that he had been receiving since the murder in New York of Elsie Sigel and the subsequent capture of the alleged murderer, a Chinese man named Leon Ling. The Chinese government ordered Lok Wing to assist in Ling’s capture. On July 31, 1909, a Chinese villain waited for Lok Wing in the corridor outside his office. Once the office guard stepped out of the door, the assassin slipped in with a gun in his hand. The wretch fired two shots when Lok Wing ran to catch him. Even though he was wounded, Lok Wing grabbed his murderer tightly. They struggled and rolled down the stairway. Lok Wing died an hour later. His friends brought him back to the peaceful and beautiful hillside of Washington, Connecticut. And there he was buried. Many government officials, including the Consul and other Chinese officials, attended his funeral.

The main reason the Ching Government abandoned the CEM was that some of the boys had converted to Christianity and adopted Western manners. Most of the boys returned to China with an incomplete Western education. Nevertheless, they tried their best to fit into the Chinese society again and serve their country. Their Western education was not appreciated by the locals in China; but still, they introduced Western technology. Some of them became railroad and mining engineers, telegraph operators, prime ministers (notably, the famous Jeme Tien Yow, known as the “Father of China’s Railways”), admirals, or naval officers; while some of them, like the ill-fated Lok Wing Chuan, became diplomats representing their own country in America.

Michelle Wong graduated from The Gunnery in 2004.