by Elizabeth J Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2010/11

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

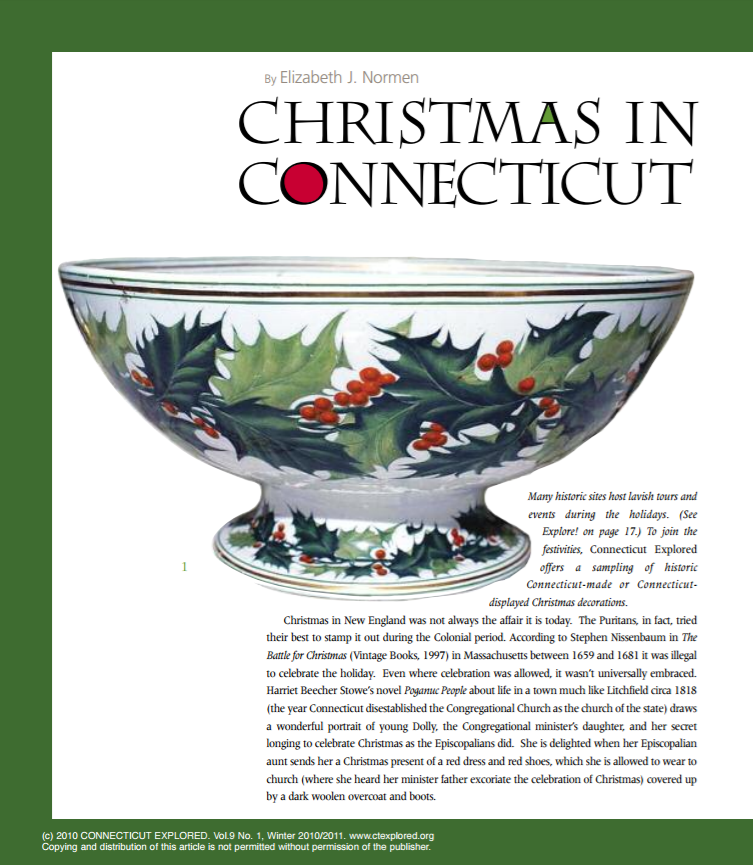

Christmas in New England was not always the affair it is today. The Puritans, in fact, tried their best to stamp it out during the Colonial period. According to Stephen Nissenbaum in The Battle for Christmas (Vintage Books, 1997) in Massachusetts between 1659 and 1681 it was illegal to celebrate the holiday. Even where celebration was allowed, it wasn’t universally embraced. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Poganuc People about life in a town much like Litchfield circa 1818 (the year Connecticut disestablished the Congregational Church as the church of the state) draws a wonderful portrait of young Dolly, the Congregational minister’s daughter, and her secret longing to celebrate Christmas as the Episcopalians did. She is delighted when her Episcopalian aunt sends her a Christmas present of a red dress and red shoes, which she is allowed to wear to church (where she heard her minister father excoriate the celebration of Christmas) covered up by a dark woolen overcoat and boots.

Christmas in New England was not always the affair it is today. The Puritans, in fact, tried their best to stamp it out during the Colonial period. According to Stephen Nissenbaum in The Battle for Christmas (Vintage Books, 1997) in Massachusetts between 1659 and 1681 it was illegal to celebrate the holiday. Even where celebration was allowed, it wasn’t universally embraced. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Poganuc People about life in a town much like Litchfield circa 1818 (the year Connecticut disestablished the Congregational Church as the church of the state) draws a wonderful portrait of young Dolly, the Congregational minister’s daughter, and her secret longing to celebrate Christmas as the Episcopalians did. She is delighted when her Episcopalian aunt sends her a Christmas present of a red dress and red shoes, which she is allowed to wear to church (where she heard her minister father excoriate the celebration of Christmas) covered up by a dark woolen overcoat and boots.

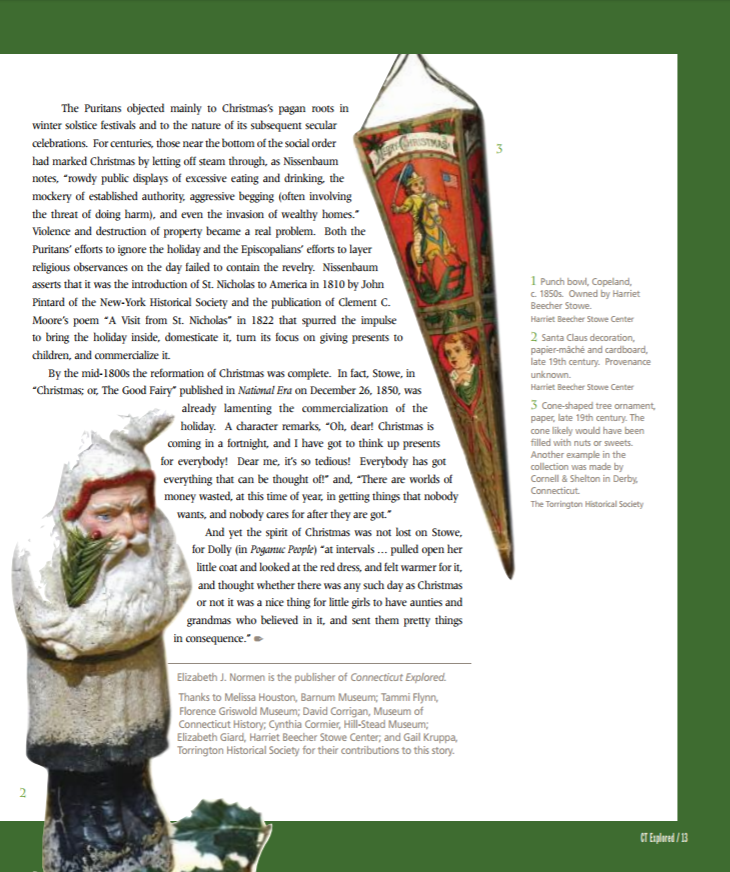

The Puritans objected mainly to Christmas’s pagan roots in winter solstice festivals and to the nature of its subsequent secular celebrations. For centuries, those near the bottom of the social order had marked Christmas by letting off steam through, as Nissenbaum notes, “rowdy public displays of excessive eating and drinking, the mockery of established authority, aggressive begging (often involving the threat of doing harm), and even the invasion of wealthy homes.” Violence and destruction of property became a real problem. Both the Puritans’ efforts to ignore the holiday and the Episcopalians’ efforts to layer religious observances on the day failed to contain the revelry. Nissenbaum asserts that it was the introduction of St. Nicholas to America in 1810 by John Pintard of the New-York Historical Society and the publication of Clement C. Moore’s poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” in 1822 that spurred the impulse to bring the holiday inside, domesticate it, turn its focus on giving presents to children, and commercialize it.

By the mid-1800s the reformation of Christmas was complete. In fact, Stowe, in “Christmas; or, The Good Fairy” published in National Era on December 26, 1850, was already lamenting the commercialization of the holiday. A character remarks, “Oh, dear! Christmas is coming in a fortnight, and I have got to think up presents for everybody! Dear me, it’s so tedious! Everybody has got everything that can be thought of!” and, “There are worlds of money wasted, at this time of year, in getting things that nobody wants, and nobody cares for after they are got.” And yet the spirit of Christmas was not lost on Stowe, for Dolly (in Poganuc People) “at intervals … pulled open her little coat and looked at the red dress, and felt warmer for it, and thought whether there was any such day as Christmas or not it was a nice thing for little girls to have aunties and grandmas who believed in it, and sent them pretty things in consequence.”

EXPLORE!

Listen to our podcasts about holidays and the way they were celebrated in Connecticut.

Episode 85: Connecticut Christmas Stories & Song

Episode 62: Three Centuries of Christmas at the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum

Episode 61: Feasts, Facts, & Fictions: Cooking REAL New England Holiday Foods

Episode 21: A Connecticut Christmas Story

Episode 20: Celebrate the Holidays with Soup and Stories