(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Three historic sites owned by Connecticut Landmarks and open to the public illustrate the importance of the land—urban, rural, and small town—in our state’s history.

On This Land, a Hero Was Born

by Rochelle Simon

The story of the Nathan Hale Homestead, childhood home of Connecticut’s state hero, centers on its agricultural history. Until 1676, the Mohegan Indian tribe used the land, in what is now Coventry, as a hunting ground, keeping it burned over to furnish good pasture for the herds of game that watered at Wangumbaug Lake. Chief Uncas left the land to his son, Attawanhood (d. 1676), who bequeathed it to a group of 15 men in Hartford, following his father’s practice of giving land to the English after their victory over his rival Sassacus in the Pequot War.

In May 1706 the Connecticut General Court appointed a committee to lay out a township on the lands deeded by Attawanhood. In the first survey of the land, completed in 1708, the area on the south side of the lake was partitioned into 78 parcels of nearly 300 acres each. Through a lottery system, the original 15 proprietors each received five lots, with the three remaining parcels reserved for a meetinghouse, a parsonage, and a school. The Connecticut General Court granted the committee rights of incorporation in 1711. Settlers from Connecticut and Massachusetts were attracted to Coventry’s grazing lands, and the town developed into a typical New England agricultural community.

Richard Hale (1717-1802) of what was then Portsmouth, Massachusetts purchased 240 acres in Coventry in 1745 and married Elizabeth Strong (1727-1767) in 1746. They had 12 children, 10 of whom survived to maturity. Nathan was the sixth. Elizabeth died in 1767, and Richard married Abigail Cobb Adams (1720-1809) in 1769. Although they did not have children together, their family was now quite large, as Abigail herself had seven children. The three youngest moved with her to the Hale homestead.

Richard Hale (1717-1802) of what was then Portsmouth, Massachusetts purchased 240 acres in Coventry in 1745 and married Elizabeth Strong (1727-1767) in 1746. They had 12 children, 10 of whom survived to maturity. Nathan was the sixth. Elizabeth died in 1767, and Richard married Abigail Cobb Adams (1720-1809) in 1769. Although they did not have children together, their family was now quite large, as Abigail herself had seven children. The three youngest moved with her to the Hale homestead.

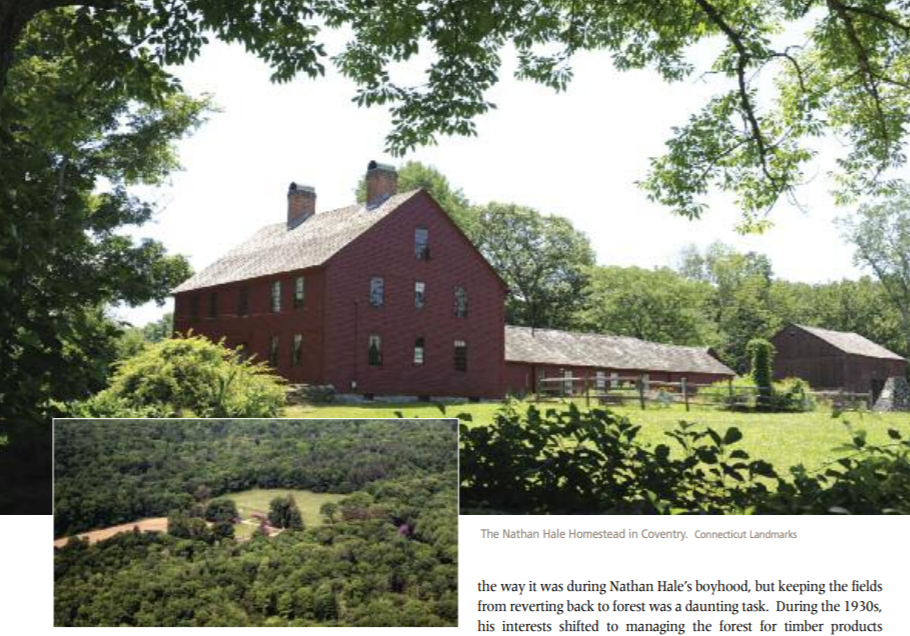

The family moved into the Georgian colonial house that still exists on the property in October of 1776, the year it was built, replacing the original house where Nathan was born. The move came just as the family learned that Nathan had been hanged as a spy on September 22, 1776. Most of the other Hale sons were away serving in the American army during the Revolution.

The center-hall “split home” was divided between two families: The rooms to the left of the hall belonged to Richard and Abigail; City, Country, Town: Connecticut Landmarks those to the right belonged to Richard’s second-eldest son John (Samuel, the eldest, was considered “infirm”) and his wife Sarah.

By 1776 the Hales owned 317 acres of land and produced most of what they ate. Primarily producers of livestock such as pigs, sheep, cattle, and geese, the Hales also had an orchard, woodlot, vegetable garden, kitchen garden, several barns, and pasture. Inventory records indicate that the family owned between 35 and 46 sheep, 3 yoke of oxen, 29 geese, 8 horses, and at least 25 heads of cattle. The house was strategically positioned to face the road to Norwich, a major route for sending livestock to market. The Hales also produced butter, cheese, tallow, soap, grease, leather, cider, and raw wool for export.

Three Hale sons died from wounds received in the war. Their widows and children moved to the family homestead, so an average of 12 to 20 people lived there at any one time. By 1798, the 450-acre Hale farm was the largest and most valuable farm in Coventry. The Hale family occupied the house until 1802; it was sold out of the family in 1838 and used thereafter as rental property.

New Haven attorney George Dudley Seymour purchased the Hale farm in 1914. His original intention was to restore the farm to the way it was during Nathan Hale’s boyhood, but keeping the fields from reverting back to forest was a daunting task. During the 1930s, his interests shifted to managing the forest for timber products and wildlife.

In 1845, Seymour bequeathed the house and 17 acres of property to Connecticut Landmarks. The Homestead is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is Connecticut Landmarks’s most visited museum property. Carrying on the Hales’ agricultural legacy, it is also the site of the state’s largest farmer’s market, open every Sunday from May to October.

In 1945, Seymour also donated to the state 850 acres of land surrounding the Homestead. The Nathan Hale State Forest now encompasses 1,500 acres of mixed hardwoods, coniferous plantations, old fields, wetlands, and agricultural lands. A 200-acre natural area, to exist with no management activity, has been established, while the rest of the forest is managed for a sustainable yield of wildlife habitat and forest products. Many people enjoy fishing along the Skungamaug River, and hunters use the forest in season. There are no official trails in the forest, though one can find old logging roads, and there is evidence of a system created by the Neighborhood Youth Corps in 1965. Those who venture in may come across cellar pits and ruins, remnants of outbuildings from the Hale Farm and neighboring farms.

Once By the Sea, Now in the City Center

By Sally Ryan & Barbara Lipsche

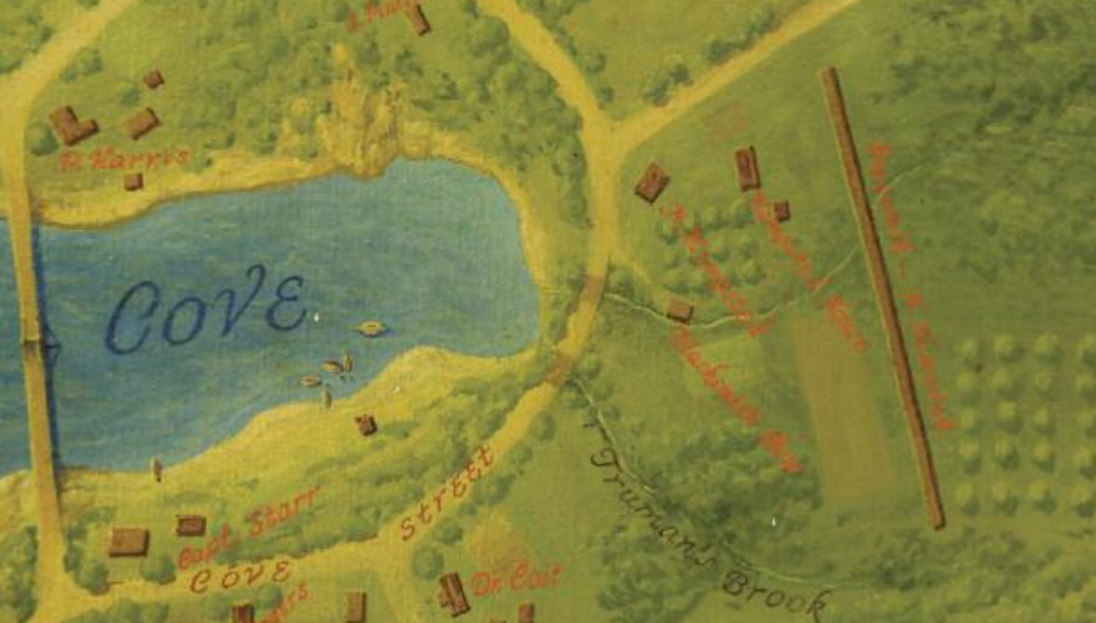

In New London’s earliest days, the Hempstead or Hempsted (both are used interchangeably) property sat on a parcel of land known simply as the “plantation in the Pequot country.” Most of New London’s original town lots were located between two bodies of water known as the Winthrop and Bream coves.

We know much about the family’s use of its land because Joshua’s son, also named Joshua, kept a detailed diary from 1711 to 1758. The diary provides a snapshot of rural life among early New London settlers and details the farming and maritime activities that occurred in the shoreline community.

Historians speculate that the Hempstead lot was once twice the size of the 14 acres Joshua, the diarist, inherited from his father. Back then it comprised a large part of the southwestern end of the New London settlement near Bream Cove, but today the property takes up just a third of an acre and sits in the midst of what is now a small city.

In those days, Colonial New London ranged from the Rhode Island border to Rocky Neck. Today, the city rests on just 5.5 square miles of land. Pequot Indians inhabiting the area before it was settled once called the area Nameaug. After their defeat in the Pequot War, the Indians were forced from the area, and the Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies claimed the land. John Winthrop, Jr. (1605/6 – 1676), son of Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, sought to lead a settlement there and was granted permission to do so in 1644. In 1646, his 36 followers settled on rural lots along the bank of the Pequot, now known as the Thames, River.

In those days, Colonial New London ranged from the Rhode Island border to Rocky Neck. Today, the city rests on just 5.5 square miles of land. Pequot Indians inhabiting the area before it was settled once called the area Nameaug. After their defeat in the Pequot War, the Indians were forced from the area, and the Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies claimed the land. John Winthrop, Jr. (1605/6 – 1676), son of Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, sought to lead a settlement there and was granted permission to do so in 1644. In 1646, his 36 followers settled on rural lots along the bank of the Pequot, now known as the Thames, River.

Among the first settlers was Robert Hempstead, a friend of Winthrop who came to New London in 1645/46 to help prepare the settlement for himself and the others. The original house Robert built no longer stands. In 1678, Robert’s son, Joshua (1649- 89), the diarists’ father, built the frame house that stands today.

When Joshua the diarist inherited the lot, it headed Bream Cove, which ran from modern-day Bank and Reed streets right up to the Hempsteads’ front yard. The Hempsteads farmed mostly outside of the house lot (they owned nearly 500 acres of land across southeastern Connecticut) but also did some small-scale farming at home. Joshua recorded some of these activities in his diary during the summer months. On July 8, 1747 he wrote, “Ye aftern I was about hay, Joshua and Joseph Lester mowed…at home below ye well…July 27th 1747, I fenced in a cabbage yard behind the house…Stephen and Joshua [son and grandson]are fencing in a turnip yard.”

The diary highlights changes in the landscape over the years. Joshua the diarist worked for a time in the Coit family shipyard and carried out smaller maritime projects at home, such as launching a rowboat from his front yard into Bream Cove. On February 1, 1716 Joshua wrote, “In ye foren I workt about ye boat & in ye aftern about oars…Mended ye Leantoo [the shed attached to his house]where ye boat went out.” Joshua’s grandson, Nathaniel (1727-1792) also played a part in the shipbuilding industry. He worked as a ropemaker and had a building on the property, called a rope walk, dedicated to making rope. Nathaniel built the stone house that still sits at the end of the property and once faced Bream Cove.

Before the Revolutionary War, New London farmers shipped such goods as horses and barrel stays to the West Indies in return for sugar, rum, and molasses. When the whaling industry took hold in 1819, a different kind of maritime commerce flourished: building ships, particularly large ones for whaling expeditions with large crews. As a result, people working in the shipping industry— from sailors to ship builders, sail makers, and barrel makers— moved into the neighborhood, and the population grew. The land’s use evolved from farming and pasturing to industrialization and housing.

The Hempsteads and other landowners in the area gradually sold off their property to make money and to help the town form housing and industrial settlements for its growing population. By 1860, New London had a population of around 10,000, and its coastline was used less for farming and more for industrial commerce. By 1845, the original Hempstead property was sold and divided into Franklin Street, Home Street, and High (now Garvin) Street. A large tannery was built there, and later several factories were also established, among them a cane/umbrella factory, a pickling and canning factory in the 1870s, and a Wash Silk company that at one time employed more than a hundred people. The area remained industrial into the 1960s.

The Hempsteads played an indirect role in New London’s cultural movements. Between 1842 and 1845, Savillion Haley, an abolitionist, used former Hempstead land to build housing for freed African-American slaves. The Hempsteads, also abolitionists, supported Haley’s efforts. These four buildings on Hempstead Street helped integrate African Americans into the community.

Over time the landscape changed. Bream Cove filled with silt, and the shipyards moved. New Londoners augmented nature’s work by filling the cove with earth and rubbish. By the end of the century, the Hempstead property had shrunk to its present size, and by the 1900s, the cove had disappeared entirely. Bank Street extended out to Waterford, and buildings stood where water once had been.

Over time the landscape changed. Bream Cove filled with silt, and the shipyards moved. New Londoners augmented nature’s work by filling the cove with earth and rubbish. By the end of the century, the Hempstead property had shrunk to its present size, and by the 1900s, the cove had disappeared entirely. Bank Street extended out to Waterford, and buildings stood where water once had been.

The evolution of the Hempstead house lot reflects New London’s development into an industrial and maritime city. The 14 acres Joshua the diarist inherited gradually transformed into a city block with housing and industries. By 1900, the Hempstead daughters and granddaughters occupied the house, domesticating it with decorative gardens. In 1942, Connecticut Landmarks purchased the frame house and later also purchased Nathaniel Hempstead’s stone house. The houses and their more-than-300- year history remain today as a testament to New London’s rich heritage.

O Little Town Of Bethlehem: Early Land Conservation

by Kristin Havill

The first pioneers moved in to the “North Purchase” of Woodbury in 1734 and began carving out farms from the wilderness of forests, rocks, and swamps. By 1740, seeking to avoid the 8-mile trip (particularly arduous in winter) into the center of Woodbury to attend church, the small community of 14 families received from the General Court of Connecticut permission to build its own church. This laid the foundation for the arrival of the community’s first minister, Reverend Joseph Bellamy, who named the settlement Bethlehem.

The parish gave Bellamy a home on a 100-acre lot, which land he purchased in 1744, the year of his marriage. Bellamy insisted from the beginning that his prime work was to minister to his flock rather than to run a farm. His salary, including supplies of fire wood and grains from the congregation, at first was sufficient to free him from the responsibilities of full-time farming. But as his family grew to include seven children, he needed both a larger house and more resources to keep the family fed. Beyond that, Bellamy housed young men whom he was training for the ministry; over time, he took in 60 of those students. So he found himself running a subsistence farm after all.

The parish gave Bellamy a home on a 100-acre lot, which land he purchased in 1744, the year of his marriage. Bellamy insisted from the beginning that his prime work was to minister to his flock rather than to run a farm. His salary, including supplies of fire wood and grains from the congregation, at first was sufficient to free him from the responsibilities of full-time farming. But as his family grew to include seven children, he needed both a larger house and more resources to keep the family fed. Beyond that, Bellamy housed young men whom he was training for the ministry; over time, he took in 60 of those students. So he found himself running a subsistence farm after all.

Through his lecturing and preaching throughout Connecticut, Reverend Bellamy, a skilled orator, became one of the most influential men in American religious life of the 18th century. Fittingly, his property had a commanding position on the hill above the town green and meeting house. After Bellamy’s death in 1790, the property stayed in the family for four generations, eventually evolving to a larger farm operation and reaching its peak size in the 1860s.

Meanwhile, Bethlehem, like other Connecticut towns with access to flowing water, began to develop industries in the 1800s. While remaining largely an agricultural community, by 1859 the town had a dozen small businesses, including a saw mill and a fabric-fulling mill with public laundry facilities. Westward migration and competition from larger industrial cities led to industry’s decline in the late 1800s, and the town’s population dwindled to 536 inhabitants by 1920. By 1912 the old Bellamy farm had changed hands several times, and the house stood vacant and in need of repair.

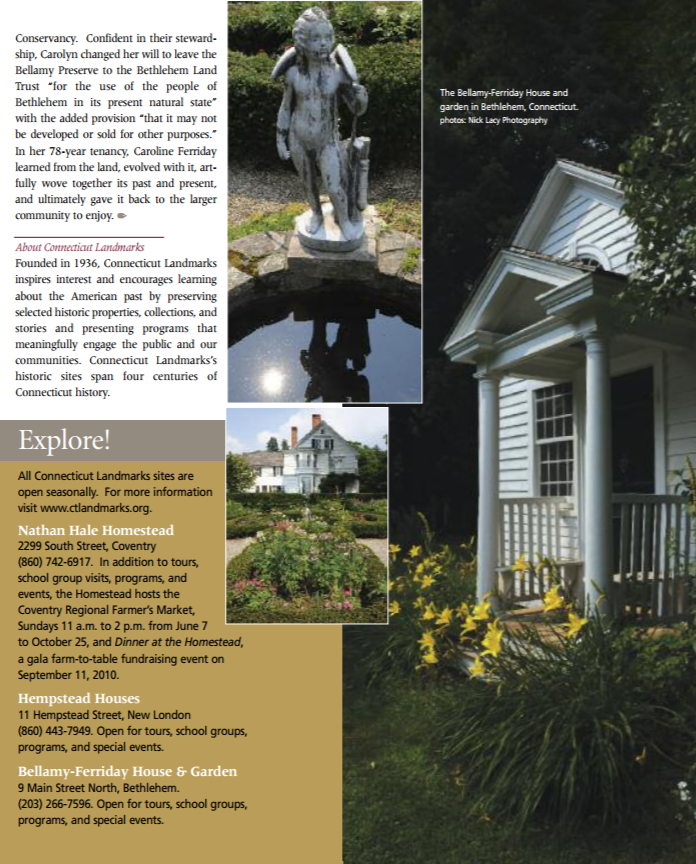

In 1912, a new phenomenon reached the sleepy town. Henry McKeen Ferriday and his wife Eliza Mitchell Ferriday of New York City bought the property for a summer residence. Their daughter Caroline recalled later “It was not a promising prospect.” The new owners installed plumbing and central heating, and the landscape began a slow transformation. Under Eliza’s direction, a formal parterre garden was installed, foundation plantings were added, and specimen trees and a screen of hemlock trees were planted along the main roads. After Eliza’s death in the 1950s, Caroline continued the artful addition of many flowering trees and shrubs throughout the property to make the site the horticultural treasure it is today.

While Caroline honed her horticultural eye and skills, she also attended to two other aspects of the landscape: the farm and the forest. She continued small-scale farming, though in a different vein from the Bellamy era’s subsistence farming. Into the late 1960s, Caroline kept a cow, horse, and chickens and maintained the orchard; local farmers hayed the fields. As she studied the life of Reverend Bellamy, she maintained the Bellamy family’s numerous outbuildings and created a space for Reverend Bellamy’s memory in the 18th-century schoolhouse on the property where he had taught his young scholars.

Caroline then focused on the northern 89 acres where as a young girl she had ridden her pony. In 1962, with the help of the Litchfield County Soil and Water Conservation District, Caroline drew up a conservation plan; seven years later she wrote to the Conservation Commission, “…several alternatives for the eventual use of the land have been proposed and it will take me time and thought to sort out the different ideas and see which one comes closest to my way of thinking… . I am so fond of the place that I really don’t like a bit the idea of leaving it!”

Before the environmental movement of the 1970s, and almost 30 years before her death in 1990, Caroline began to search in earnest for the right stewards for her woodland property. Having never married and with no direct heirs, she began looking for those who would as sure the long-term preservation of the land that she loved.

The Commission drew up a new management plan in January 1969. By 1978, however, Caroline had reservations about the Commission’s suitability to carry out long-range stewardship responsibilities. Having willed the house and homelot to the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society (now Connecticut Landmarks), she was concerned about the future of the surrounding land. In March 1979 she leased 89 acres to the Nature Conservancy’s Connecticut Chapter with the intention to will it to them upon her death.

By December 1979 the Bethlehem Conservation District’s interest in the property had spurred the legal formation of the Bethlehem Land Trust. Carolyn’s decision to work with the Nature Conservancy turned out to be the catalyst for its creation. The group quickly organized a Bellamy Preserve Stewardship committee to over see property management under the direction of the Conservancy. Confident in their stewardship, Carolyn changed her will to leave the Bellamy Preserve to the Bethlehem Land Trust “for the use of the people of Bethlehem in its present natural state” with the added provision “that it may not be developed or sold for other purposes.” In her 78-year tenancy, Caroline Ferriday learned from the land, evolved with it, artfully wove together its past and present, and ultimately gave it back to the larger community to enjoy.

Rochelle Simon is the former director of communications and marketing for Connecticut Landmarks. Sally Ryan is municipal historian for the City of New London and tour coordinator for the Hempstead Houses. Barbara Lipsche is a freelance writer. Kristin Havill is site administrator for the Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden.

Explore!

Connecticut Landmarks

Founded in 1936, Connecticut Landmarks inspires interest and encourages learning about the American past by preserving selected historic properties, collections, and stories and presenting programs that meaning fully engage the public and our communities. Connecticut Landmarks’s historic sites span four centuries of Connecticut history. ctlandmarks.org

More stories about Connecticut Landmarks properties:

Destination: Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden, Summer 2008

Caroline Ferriday: A Godmother to Ravensbruck Survivors, Winter 2011/2012

Caroline Ferriday and her Infinitely Generous Family, Fall 2019

The Butler-McCook House, Winter 2003

Saving Hartford’s Amos Bull House, Summer 2015

A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House, Fall 2019

Destination: Nathan Hale Homestead, Fall 2005