(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In his pioneering book Women of War, published just two years after the close of the Civil War, the noted 19th-century historian and author Frank Moore wrote:

The story of the war will never be fully or fairly written if the achievements of women in it are untold. They do not figure in the official reports, they are not gazetted for deeds as gallant as ever were done; the names of thousands are unknown beyond the neighborhood where they live, or the hospitals where they loved to labor; yet there is no feature in our war more creditable to us as a nation.…

With the advent of the Civil War, the roles of women were significantly altered as new and monumental responsibilities took precedence over those that were considered the normal female domain. The security of the traditional family structure and community cohesion was suddenly assaulted by the loss of so many husbands, fathers, and sons to the battlefield, and the overwhelming need to supply the continually demanding war machine with food, arms, uniforms, and medical supplies. Just as during World War II era, during the Civil War women were entrusted with maintaining the North’s industry. The demands of the Civil War stimulated the expansion of women’s roles in society and in the industrial world.

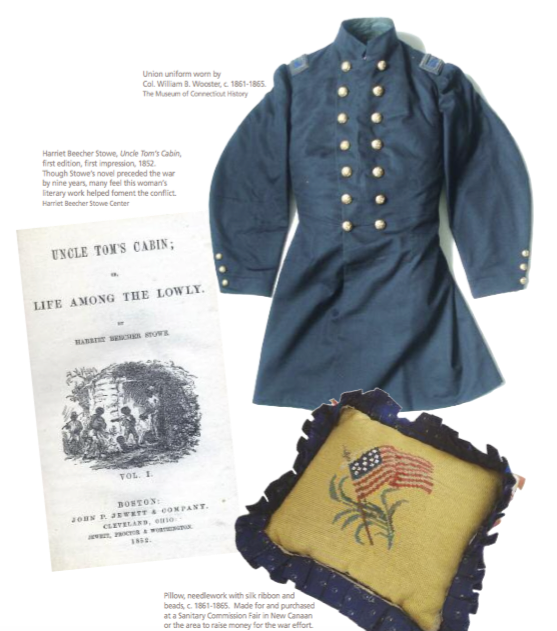

Already established local sewing circles and Christian associations easily and quickly transformed into Soldiers’ Aid Societies (the nation’s first was created in Bridgeport) as members of these community organizations banded together to coordinate provisions to be shipped to the front. Rolling bandages, scraping lint, sewing, knitting, and collecting donations were tasks eagerly pursued by many women concerned about the welfare of loved ones and their comrades. Barbara E. Lacy noted, “Three hundred Norwich women met a few days after the fall of Fort Sumter in order to make uniforms for their town’s company. New Haven women turned out 500 uniforms while East Hartford women made 6,000 yards of bandages and hundreds of compresses.” [source no longer available]

In Bridgeport, The Ladies’ Relief Society (formed in 1861), The Soldiers’ Aid Society (organized in 1862), and League of Loyal Women of Bridgeport (formed in 1863) functioned as direct connections to the United States Sanitary Commission and were charged with gathering supplies, sending several thousand barrels and boxes of provisions including hospital supplies, clothing, personal affects, food and vegetables to Connecticut regiments in the field. Raising thousands of dollars in relief support, these organizations actively worked to encourage community loyalty for the Union cause and to promote patriotism at home. According to Lacy, “The Hartford Society of Women paid $20,000 in cash and sent $60,000 worth of goods to the troops.” The United States Sanitary Commission was established in June 1861 as a benevolent war relief agency to act as a centralized clearinghouse for informing women in local organizations of the immediate needs in the field.

Meanwhile, many families were left destitute by the absence of breadwinners, as pay for soldiers was low and often in arrears. The government was not prepared or equipped to assist dependents of the army. No form of insurance or pensions had yet been established, and the government suspended the pay of a prisoner until he was reunited with his regiment. In an era when accepting charity was considered demeaning, the necessity to survive sent many women and children into the workplace. Compelled to provide for their families, these women developed an attitude of self-reliance, and public apprehension of female independence adapted to women’s new role.

According to the 1860 census, one quarter of the manufacturing work force was already composed of women. The war created new opportunities for women in arsenals (making munitions and wrapping dangerous explosive-cartridge packages), sewing rooms, and offices. Wages, however, were often very low, hours exhaustingly long, and working conditions poor and sometimes dangerous. On the positive side, the U.S. government, including the War Department and Department of the Interior, hired women as clerks and copyists. The Post Office soon followed and began hiring postmistresses. Women entered the teaching and nursing professions in large numbers, eventually becoming identified with these professions.

According to the 1860 census, one quarter of the manufacturing work force was already composed of women. The war created new opportunities for women in arsenals (making munitions and wrapping dangerous explosive-cartridge packages), sewing rooms, and offices. Wages, however, were often very low, hours exhaustingly long, and working conditions poor and sometimes dangerous. On the positive side, the U.S. government, including the War Department and Department of the Interior, hired women as clerks and copyists. The Post Office soon followed and began hiring postmistresses. Women entered the teaching and nursing professions in large numbers, eventually becoming identified with these professions.

The Civil War accelerated the emancipation of women in society. Their selfless dedication to a cause had given women an opportunity to move outside the domestic sphere.

With the ending of the war at Appomattox, and the return of the troops to take up their civilian lives, the women who had maintained the home front for four long years found themselves being displaced, yet reluctant to return to their pre-war standing. Many of them, having tasted the independence of responsibility, continued their work in the community, joined the work force in more varied occupations, and attended colleges and universities in greater numbers, taking active steps to regain the freedom and power they had assumed during the Civil War.

Kathleen Maher is the executive director and curator of the Barnum Museum in Bridgeport.

Explore!

Heroes of the Home Front; Life North of the Battlefield

The Barnum Museum

barnum-museum.org

Read more stories about Connecticut in the Civil War in our Spring 2011 and Winter 2012/2013 issues, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.